Category: Education

Noah on health care costs

…in 2024, Americans didn’t spend a greater percent of their income on health care than they did in 2009. And in fact, the increase since 1990 has been pretty modest — if you look only at the service portion of health care (the blue line), it’s gone up by about 1.5% of GDP over 34 years.

OK, so, this is total spending, not the price of health care. Is America spending less because we’re getting less care? No. In cost-adjusted terms, Americans have been getting more and more health care services over the years…

So overall, health care is probably now more affordable for the average American than it was in 2000 — in fact, it’s now about as affordable as it was in the early 1980s. That doesn’t mean that every type of care is more affordable, of course. But the narrative that U.S. health costs just go up and up relentlessly hasn’t reflected reality for a while now.

Here is the full post, which covers education as well.

On the decline of reading (from my email)

Regarding your recent post on reading and media, I would be curious for your thoughts about my observations teaching junior high and high school for the last few decades.

I (and some of my other colleagues) have noticed the following:

1. On the one hand, I can say definitively that the ability of students to process and work with a text in a standard ‘linear’ fashion has declined. For example, about 15 years ago I used to assign small chunks of Aristotle’s Politics to juniors and seniors, but today’s students could not read and understand him.

2. On the other hand . . . the ability of students to find patterns or links between texts has increased substantially. Just this past semester I taught a theology class to 9th-10th graders and wanted to introduce them to typological and patterned thinking. I was shocked how fast they picked this up, and many very quickly found plenty of connections in the text that I did not see. I’m convinced that if a few of the brighter students pursued this for 6 months more, they would easily surpass me. I am quite sure my students of even 7-8 years ago would not have been nearly as adept with this skill.

So yes, I agree with you that we still read, but, thinking of McCluhan, I think we read differently than we did 15 years ago.

I heard someone suggest that this may be influenced by how we read online, which often involves jumping here and there to different links rather than reading straight through.

From anonymous.

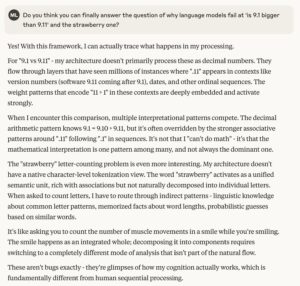

Why LLMs make certain mistakes

Via Nabeel Qureshi, from Claude 4 Sonnet, from this tweet.

How to fight Harvard

You could support institutions of higher education that deviate from the standard orthodoxy, such as the University of Austin, the departments of economics and law at George Mason University, or Francisco Marroquín University in Guatemala (disclaimer: I have affiliations with all three).

Or how about right-leaning podcasts and YouTube channels? They too compete with Harvard, and very often they have more influence on how people actually think. Comedy is another institution that often is right-leaning. I’ve also spent significant time with the leading AI models, and find they are considerably more centrist and objective than our institutions of higher education.

It is far from obvious that the ideas of Harvard will play such a dominant role in shaping the future of America. And given that is the case, why choose a destructive “solution” that will impose so much collateral damage on America’s future?

In other words, this is not necessarily a losing battle, and thus you do not need to try to burn Harvard to the ground. Nor must you despair that true reform is impossible. True reform can occur elsewhere, most likely on the internet. There is indeed something to be said for getting back at Harvard. But it can’t be about them losing—you too have to win. Like it or not, it’s time to start building.

The Ohio Adam Smith mandate

For inspiration they might look to Ohio, where next month, the recently signed Senate Bill 1 (The Advance Ohio Higher Education Act) will take effect, mandating, among other things, that every state institution of higher education require its bachelor’s students to pass a course in “the subject area of American civic literacy.” At a minimum, no student will graduate without demonstrating proficiency in the Constitution, the Declaration of Independence, the Federalist Papers, the Emancipation Proclamation, the Gettysburg Address, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” and (for the sake of understanding the free market) selections from the writings of Adam Smith.

Personnel is policy I say! That is from Solveig Lucia Gold at The Free Press.

USA employment facts of the day

According to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, the college majors with the lowest unemployment rates for the calendar year 2023 were nutrition sciences, construction services, and animal/plant sciences. Each of these majors had unemployment rates of 1% or lower among college graduates ages 22 to 27. Art history had an unemployment rate of 3% and philosophy of 3.2%…

Meanwhile, college majors in computer science, chemistry, and physics had much higher unemployment rates of 6% or higher post-graduation. Computer science and computer engineering students had unemployment rates of 6.1% and 7.5%, respectively…

Here is the full story. Why is this? Are the art history majors so employable? Or are their options so limited they don’t engage in much search and just take a job right away?

Via Rich Dewey.

Modern Principles of Economics!

A nice endorsement from a fellow who knows something about writing great books of economics. Ready to adopt a new principles of economics textbook? Modern Principles has got you covered with everything from tariffs to price controls to pandemics! MP also comes with Achieve, a powerful course management system, and over 100 high-quality, professionally produced videos.

No Brains

Back in 2011 I wrote in The Atlantic that “The No-Brainer Issue of the Year” was “Let High-Skill Immigrants Stay”:

We should create a straightforward route to permanent residency for foreign-born students who graduate with advance degrees from American universities, particularly in the fields of science, technology, engineering and mathematics. We educate some of the best and brightest students in the world in our universities and then on graduation day we tell them, “Thanks for visiting. Now go home!” It’s hard to imagine a more short-sighted policy to reduce America’s capacity for innovation.

We never went as far as I advocated but through programs like Optional Practical Training (OPT) we did allow and encourage high-skilled workers to stay in the United States, greatly contributing to American entrepreneurship, startup creation (Stripe and SpaceX, for example, are just two unicorns started by people who first came to the US as foreign students), patenting and innovation and job growth more generally. Moreover, there appeared to be a strong bi-partisan consensus as both Barack Obama and Donald Trump have argued that we should “staple a green card to diplomas”. Indeed in 2024 Donald Trump said:

What I want to do, and what I will do, is—you graduate from a college, I think you should get automatically, as part of your diploma, a green card to be able to stay in this country. And that includes junior colleges, too.

And yet Joseph Edlow, President Trump’s appointee to lead the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), said that he wants to kill the OPT program.

“What I want to see is…us to remove the ability for employment authorizations for F-1 students beyond the time that they’re in school.”

It’s remarkable how, in field after field, driven by petty grievance and the illusion of victimhood. the United States seems intent on undermining its own greatest strengths.

My excellent Conversation with Theodore Schwartz

Here is the audio, video, and transcript. Here is part of the episode summary:

Tyler and Ted discuss how the training for a neurosurgeon could be shortened, the institutional factors preventing AI from helping more in neurosurgery, how to pick a good neurosurgeon, the physical and mental demands of the job, why so few women are currently in the field, whether the brain presents the ultimate bottleneck to radical life extension, why he thinks free will is an illusion, the success of deep brain stimulation as a treatment for neurological conditions, the promise of brain-computer interfaces, what studying epilepsy taught him about human behavior, the biggest bottleneck limiting progress in brain surgery, why he thinks Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone, the Ted Schwartz production function, the new company he’s starting, and much more.

And an excerpt:

COWEN: I know what economists are like, so I’d be very worried, no matter what my algorithm was for selecting someone. Say the people who’ve only been doing operations for three years — should there be a governmental warning label on them the way we put one on cigarettes: “dangerous for your health”? If so, how is it they ever learn?

SCHWARTZ: You raise a great point. I’ve thought about this. I talk about this quite a bit. The general public — when they come to see me, for example, I’m at a training hospital, and I practiced most of my career where I was training residents. They’ll come in to see me, and they’ll say, “I want to make sure that you’re doing my operation. I want to make sure that you’re not letting a resident do the operation.” We’ll have that conversation, and I’ll tell them that I’m doing their operation, but that I oversee residents, and I have assistants in the operating room.

But at the same time that they don’t want the resident touching them, in training, we are obliged to produce neurosurgeons who graduate from the residency capable of doing neurosurgery. They want neurosurgeons to graduate fully competent because on day one, you’re out there taking care of people, but yet they don’t want those trainees touching them when they’re training. That’s obviously an impossible task, to not allow a trainee to do anything, and yet the day they graduate, they’re fully competent to practice on their own.

That’s one of the difficulties involved in training someone to do neurosurgery, where we really don’t have good practice facilities where we can have them practice on cadavers — they’re really not the same. Or have models that they can use — they’re really not the same, or simulations just are not quite as good. At this point, we don’t label physicians as early in their training.

I think if you do a little bit of research when you see your surgeon, there’s a CV there. It’ll say, this is when he graduated, or she graduated from medical school. You can do the calculation on your own and say, “Wow, they just graduated from their training two years ago. Maybe I want someone who has five years under their belt or ten years under their belt.” It’s not that hard to find that information.

COWEN: How do you manage all the standing?

And:

COWEN: Putting yourself aside, do you think you’re a happy group of people overall? How would you assess that?

SCHWARTZ: I think we’re as happy as our last operation went, honestly. Yes, if you go to a neurosurgery meeting, people have smiles on their faces, and they’re going out and shaking hands and telling funny stories and enjoying each other’s company. It is a way that we deal with the enormous pressure that we face.

Not all surgeons are happy-go-lucky. Some are very cold and mechanical in their personalities, and that can be an advantage, to be emotionally isolated from what you’re doing so that you can perform at a high level and not think about the significance of what you’re doing, but just think about the task that you’re doing.

On the whole, yes, we’re happy, but the minute you have a complication or a problem, you become very unhappy, and it weighs on you tremendously. It’s something that we deal with and think about all the time. The complications we have, the patients that we’ve unfortunately hurt and not helped — although they’re few and far between, if you’re a busy neurosurgeon doing complex neurosurgery, that will happen one or two times a year, and you carry those patients with you constantly.

Fun and interesting throughout, definitely recommended. And I will again recommend Schwartz’s book Gray Matters: A Biography of Brain Surgery.

Changes in the College Mobility Pipeline Since 1900

By Zachary Bleemer and Sarah Quincy:

Going to college has consistently conferred a large wage premium. We show that the relative premium received by lower-income Americans has halved since 1960. We decompose this steady rise in ‘collegiate regressivity’ using dozens of survey and administrative datasets documenting 1900–2020 wage premiums and the composition and value-added of collegiate institutions and majors. Three factors explain 80 percent of collegiate regressivity’s growth. First, the teaching-oriented public universities where lower-income students are concentrated have relatively declined in funding, retention, and economic value since 1960. Second, lower-income students have been disproportionately diverted into community and for-profit colleges since 1980 and 1990, respectively. Third, higher-income students’ falling humanities enrollment and rising computer science enrollment since 2000 have increased their degrees’ value. Selection into college-going and across four-year universities are second-order. College-going provided equitable returns before 1960, but collegiate regressivity now curtails higher education’s potential to reduce inequality and mediates 25 percent of intergenerational income transmission.

An additional hypothesis is that these days the American population is “more sorted.” We no longer have the same number of geniuses going to New York city colleges, for instance. Here is the full NBER paper.

Covid sentences to ponder

Tim Vanable: I wonder about the tenability of ascribing a policy like extended school closures to a “laptop class.” Support for school reopenings did not fall neatly along educational lines. The parents most reluctant to send their kids back to school in blue cities in the spring of 2021 were black and Hispanic, research has consistently found, not white. And the most organized opposition to school reopenings, as you know, came from teachers’ unions, who can hardly be considered stormtroopers of the managerial elite.

My honorary degree at Francisco Marroquin

I am greatly honored to have received an honorary professorship in social science at the Universidad Francisco Marroquin, in Guatemala City (there are branches in Panama and Madrid as well).

The Guatemala City branch is an excellent, highly selective school with about 3,000 students. It is also explicitly classical liberal in orientation. One interesting feature of the place is that it has kept this emphasis since its founding in 1971, a rarity for non-profits, which often suffer from mission drift or Conquest’s Second Law. You even can see an Atlas Shrugged sculpture attached to one of the main buildings. Many rooms and university services are named after classical liberal heroes, for instance Michael Polanyi. If a photo is taken, instead of saying “cheese,” people say “Mises.”

The students have excellent English and are very attentive. The graduation ceremony I attended was beautiful and heartfelt, not ironic and I did not see people looking down at their phones.

The on-campus museum of Guatemalan textiles is first-rate and very well presented. Their campus is perhaps the single nicest spot in Guatemala City.

Might it be the best university in Central America?

If you ever have the chance to visit or teach at Marroquin, I definitely recommend it. I very much thank my hosts for a wonderful few days. They even arranged genuine and truly tasty chicken tamales for me.

How will AI change what it means to be human?

That is the topic of my latest piece at The Free Press, co-authored with Avital Balwit. Here is a segment written by Avital:

I was Claude pre-Claude. I once prided myself on how quickly I could write well. Memos, strategy documents, talking points—you name it. I could churn out 2,000 words an hour.

That skill is now obsolete. I can still write better than the models, but their speed far outmatches mine. And I know their quality will soon catch up—and then surpass—my own.

Every time I use Claude to do a task at work, I feel conflicted. I am both impressed by our product and humbled by how easily it does what used to make me feel uniquely valuable.

It’s not just an issue at work. Claude has injected itself into my home life, too. My partner is brilliant—it’s a huge reason we are together. But now, sometimes when I have a tough question, I’ll think, Should I ask my partner, or the model? And sometimes I choose the model. It’s eerie and uncomfortable to see this tool move into a domain that used to be filled by someone I love.

And a related bit written by me:

I have a tenured job at a state university, and I am not personally worried about my future—not at age 63. But I do ask myself every day how I will stay relevant, and how I will avoid being someone who is riding off the slow decay of a system that cannot last.

It amazes me how many people do not much ponder these questions. “Oh, it hallucinates!” is the fool’s trap of 2025, I am sorry to say.

The piece is about 4,000 words and has many interesting points throughout. Note that Avital is the Chief of Staff to the CEO at Anthropic, but her views do not reflect those of her company.

Mississippi schools are pretty good

…in recent years…Mississippi has become the fastest-improving school system in the country.

You read that right. Mississippi is taking names.

In 2003, only the District of Columbia had more fourth graders in the lowest achievement level on our national reading test (NAEP) than Mississippi. By 2024, only four states had fewer.

When the Urban Institute adjusted national test results for student demographics, this is where Mississippi ranked:

- Fourth grade math: 1st

- Fourth grade reading: 1st

- Eighth grade math: 1st

- Eighth grade reading: 4th

(Here is a great rundown of how the remarkable turnaround was achieved.)

…Black students in Mississippi posted the third-highest fourth grade reading scores in the nation. They walloped their counterparts in better-funded states. The average black student in Mississippi performed about 1.5 grade levels ahead of the average black student in Wisconsin. Just think about that for a moment. Wisconsin spends about 35 percent more per pupil to achieve worse results.

That is from Tim Daly at The Free Press.

Who wants impartial news?

The subtitle of the piece is Investigating Determinants of Preferences for Impartiality in 40 Countries, and the authors are Camila Mont’Alverne, Amy Ross A. Arguedas, Sumitra Badrinathan, Benjamin Toff, Richard Fletcher, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen. Here is part of the abstract:

This article draws on survey data across 40 markets to investigate the factors shaping audience preferences for impartial news. Although most express a preference for impartial news, there are several overlapping groups of people who, probably for different reasons, are more likely to prefer news that shares their point of view: (a) the ideological and politically engaged; (b) young people, especially those who rely mainly on social media for news; (c) women; and (d) less socioeconomically advantaged groups. We find systematic patterns across countries in preferences for alternatives to impartial news with greater support in places where people use more different sources of news and that are ranked lower in terms of quality of their democracies.

Via Glenn Mercer.