Category: Film

*Pee-wee as himself*

I loved this documentary, all three hours of it. Perhaps you need to be American, and to have lived in Pee-wee’s decades? In any case, the film is a wonderful reflection on self-knowledge, the changing status of “coming out” as gay in American history, celebrity, how fame happens, hippie culture, cancel culture, who your real friends are, narcissism, and much more. Pee-wee collaborated with the making of the film, but it seems pretty honest in portraying his life and later legal troubles. It turns out he was dying of cancer for years, but did not let on to the filmmakers. Here is the official trailer.

*Resurrection*

That is the new Chinese movie, noting that the original title translates better as “Feral/Wild Age,” and you can think of it as a retelling of the history of the 20th century, from a Straussian Chinese point of view. Are parts also a retelling of the Buddha story, but what if a Buddha came to earth in contemporary times? Toss in “Chinese Ghost Story” and some vampires, and you have a pretty strange mix. Here is a good critical overview, including an interview with the director Bi Gan.

Scott Sumner noted he may well end up considering this to be his favorite movie of the decade. Visually, it is one of the most interesting movies of the last twenty-five years. Also, the attentive viewer will catch visual references to Dreyer, Uncle Boonmee, Stalker, Enter the Dragon, Rashomon, David Lynch, Matt Barney, and much more. Resurrection is also a homage to cinema, and to the passing of cinema, I would say.

As for the plot, I still am not sure. Perhaps it demands repeat viewings? I do not feel it is a spoiler to tell you there is one character taking five different guises. In any case, this is a major work of creative art and I am very glad I saw it. Large screen is mandatory of course.

Stories Beyond Demographics

The representation theory of stories, where the protagonist must mirror my gender, race, or sexuality for me to find myself in the story, offers a cramped view of what fiction can do and a shallow account of how it actually works. Stories succeed not through mirroring but by revealing human patterns that cut across identity. Archetypes like Hero, Caregiver, Explorer, and Artist, and structures like Tragedy, Romance, and Quest are available to everyone. That is why a Japanese salaryman can love Star Wars despite never having been to space or met a Wookie and why an American teenager can recognize herself in a nineteenth-century Russian novel.

Tom Bogle makes this point well in a post on Facebook:

I have no issue with people wanting representation of historically marginalized people in stories. I understand that people want to “see themselves” in the story.

But it is more important to see the stories in ourselves than to see ourselves in the stories.

When we focus on the representation model, we recreate a character to be an outward representation of physical traits. Then the internal character traits of that individual become associated with the outward physical appearance of the character and we pigeonhole ourselves into thinking that we are supposed to relate only to the character that looks like us. Movies and TV shows have adopted the Homer Simpson model of the aloof, detached, and even imbecilic father, and I, as a middle-aged cis het white guy with seven kids could easily fall into the trap of thinking that is the only character to whom I can relate. It also forces us to change the stories and their underlying imagery in order to fit our own narrative preferences, which sort of undermines the purpose for retelling an old story in the first place.

The archetypal model, however, shifts our way of thinking. Instead of needing to adapt the story of Little Red-Cap (Red Riding Hood) to my own social and cultural norms so that I can see myself in the story, I am tasked with seeing the story play out in myself. How am I Riding Hood? How am I the Wolf? How does the grandmother figure appear in me from time to time? Who has been the Woodsman in my life? How have I been the Woodsman to myself or others? Even the themes of the story must be applied to my patterns of behavior or belief systems, not simply the characters. This model also enables us to retain the integrity of the versions of these stories that have withstood the test of time.

So if your goal is actually to affect real social change through stories, I would encourage you to consider how the archetypal approach may actually be more effective at accomplishing your aims than the representational approach alone (as they are not necessarily in conflict with one another).

What is the greatest artwork of the century so far?

That question is taken from a recent Spectator poll. Their experts offer varied answers, so I thought at the near quarter-century mark I would put together my own list, relying mostly on a seat of the pants perspective rather than comprehensiveness. Here goes:

Cinema

Uncle Boonmee, In the Mood for Love, Ceylan’s Winter Sleep, Yi Yi, Artificial Intelligence, Her, Y Tu Mama Tambien, Four Months Three Weeks Two Days, from Iran A Separation, Oldboy, Silent Light (Reygadas), The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada, Get Back, The Act of Killing, Master and Commander, Apocalypto, and New World would be a few of my picks. Incendies anyone?

Classical music (a bad term these days, but you know what I mean):

Georg Friedrich Haas, 11,000 Strings, Golijov’s Passion, John Adams Transmigration of Souls, The Dharma at Big Sur, Caroline Shaw, and Stockhausen’s Licht operas perhaps. Typically such works need to be seen live, as streaming is no substitute. As for recordings, recorded versions of almost every classic work are better than before, opera being excluded from that generalization. So the highest realizations of most classical music compositions have come in the last quarter century.

Fiction

Ferrante, the first two volumes of Knausgaard, Submission, Philip Pullman, and The Three-Body Problem. The Marquez memoir and his kidnapping book, both better than his magic realism. The Savage Detectives. Sonia and Sunny maybe?

Visual Arts

Bill Viola’s video art, Twombly’s Lepanto series, Cai Guo-Qiang and Chinese contemporary art more generally (noting it now seems to be in decline), the large Jennifer Bartlett installation that was in MOMA, Robert Gober. Late Hockney and Richter works. The best of Kara Walker. The second floor of MOMA and so much of what has been shown there.

Jazz

There is so much here, as perhaps the last twenty-five years have been a new peak for jazz, even as it fades in general popularity. One could mention Craig Taborn, Chris Potter, and Marcus Gilmore, but there are dozens of top tier creators. Cecile McLorin Salvant on the vocal side. Is she really worse than Ella Fitzgerald? I don’t think so.

Popular music (also a bad term)

The best of Wilco, Kanye, D’angelo, Frank Ocean, Bob Dylan’s Love and Theft. How about Sunn O)))? No slight intended to those listed, but I had been hoping this category would turn out a bit stronger?

Television

The Sopranos, the first two seasons of Battlestar Galactica, Srugim, Borgen, and Curb Your Enthusiasm.

Assorted

Hamilton, and there is plenty more in theater I have not seen. At the very least one can cite Stoppard’s Coast of Utopia and Leopoldstadt. There is games and gaming. People around the world, overall, look much better than ever before. The Museum of Islamic Art in Doha and the reoopened Great Egyptian Museum in Cairo. The new wing at MOMA. Architecture might need a post of its own, but I’ll start by citing the works of Peter Zumthor. (Here is one broader list, it strikes me as too derivative in style, in any case it is hard to get around and see all these creations, same problem as with judging theatre.) I do not follow poetry much, but Louise Glück and Seamus Heaney are two picks, both with many works in the new century. The top LLMs, starting (but not ending) with GPT-4. They are indeed things of beauty.

Overall, this list seems pretty amazing to me. We are hardly a culture in decline.

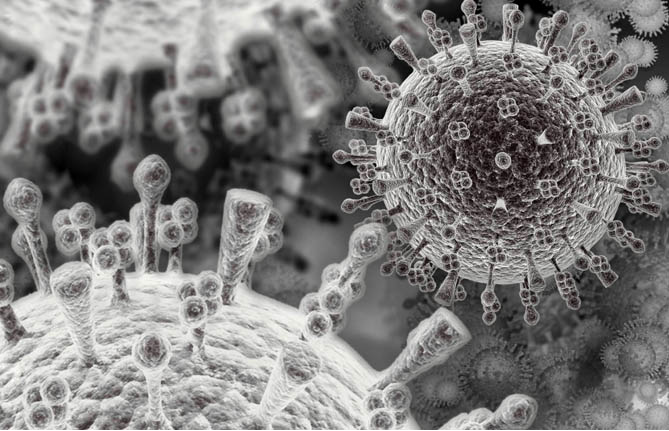

My 2011 Review of Contagion

I happened to come across my 2011 review of the Steven Soderberg movie, Contagion and was surprised at how much I was thinking about pandemics prior to COVID. In the review, I was too optimistic about the CDC but got the sequencing gains right. I continue to like the conclusion even if it is a bit too clever by half. Here’s the review (no indent):

Contagion, the Steven Soderberg film about a lethal virus that goes pandemic, succeeds well as a movie and very well as a warning. The movie is particularly good at explaining the science of contagion: how a virus can spread from hand to cup to lip, from Kowloon to Minneapolis to Calcutta, within a matter of days.

One of the few silver linings from the 9/11 and anthrax attacks is that we have invested some $50 billion in preparing for bio-terrorism. The headline project, Project Bioshield, was supposed to produce vaccines and treatments for anthrax, botulinum toxin, Ebola, and plague but that has not gone well. An unintended consequence of greater fear of bio-terrorism, however, has been a significant improvement in our ability to deal with natural attacks. In Contagion a U.S. general asks Dr. Ellis Cheever (Laurence Fishburne) of the CDC whether they could be looking at a weaponized agent. Cheever responds:

Someone doesn’t has to weaponize the bird flu. The birds are doing that.

That is exactly right. Fortunately, under the umbrella of bio-terrorism, we have invested in the public health system by building more bio-safety level 3 and 4 laboratories including the latest BSL3 at George Mason University, we have expanded the CDC and built up epidemic centers at the WHO and elsewhere and we have improved some local public health centers. Most importantly, a network of experts at the department of defense, the CDC, universities and private firms has been created. All of this has increased the speed at which we can respond to a natural or unnatural pandemic.

In 2009, as H1N1 was spreading rapidly, the Pentagon’s Defense Threat Reduction Agency asked Professor Ian Lipkin, the director of the Center for Infection and Immunity at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health, to sequence the virus. Working non-stop and updating other geneticists hourly, Lipkin and his team were able to sequence the virus in 31 hours. (Professor Ian Sussman, played in the movie by Elliott Gould, is based on Lipkin.) As the movie explains, however, sequencing a virus is only the first step to developing a drug or vaccine and the latter steps are more difficult and more filled with paperwork and delay. In the case of H1N1 it took months to even get going on animal studies, in part because of the massive amount of paperwork that is required to work on animals. (Contagion also hints at the problems of bureaucracy which are notably solved in the movie by bravely ignoring the law.)

It’s common to hear today that the dangers of avian flu were exaggerated. I think that is a mistake. Keep in mind that H1N1 infected 15 to 30 percent of the U.S. population (including one of my sons). Fortunately, the death rate for H1N1 was much lower than feared. In contrast, H5N1 has killed more than half the people who have contracted it. Fortunately, the transmission rate for H5N1 was much lower than feared. In other words, we have been lucky not virtuous.

We are not wired to rationally prepare for small probability events, even when such events can be devastating on a world-wide scale. Contagion reminds us, visually and emotionally, that the most dangerous bird may be the black swan.

What Tom Whitwell learned in 2025

52 things, here is one of them:

Most characters in the film Idiocracy wear Crocs because the film’s wardrobe director thought they were too horrible-looking to ever become popular. [Alex Kasprak]

Here is the full list.

My Conversation with the excellent Dan Wang

Here is the audio, video, and transcript. Here is part of the episode summary:

Tyler and Dan debate whether American infrastructure is actually broken or just differently optimized, why health care spending should reach 35% of GDP, how lawyerly influences shaped East Asian development differently than China, China’s lack of a liberal tradition and why it won’t democratize like South Korea or Taiwan did, its economic dysfunction despite its manufacturing superstars, Chinese pragmatism and bureaucratic incentives, a 10-day itinerary for Yunnan, James C. Scott’s work on Zomia, whether Beijing or Shanghai is the better city, Liu Cixin and why volume one of The Three-Body Problem is the best, why contemporary Chinese music and film have declined under Xi, Chinese marriage markets and what it’s like to be elderly in China, the Dan Wang production function, why Stendhal is his favorite novelist and Rossini’s Comte Ory moves him, what Dan wants to learn next, whether LLMs will make Tyler’s hyper-specific podcast questions obsolete, what flavor of drama their conversation turned out to be, and more.

Excerpt:

COWEN: When will Chinese suburbs be really attractive?

WANG: What are Chinese suburbs? You use this term, Tyler, and I’m not sure what exactly they mean.

COWEN: You have a yard and a dog and a car, right?

WANG: Yes.

COWEN: You control your school district with the other parents. That’s a suburb.

WANG: How about never? I’m not expecting that China will have American-style suburbs anytime soon, in part because of the social engineering projects that are pretty extensive in China. I think there is a sense in which Chinese cities are not especially dense. Indian cities are much, much more dense. I think that Chinese cities, the streets are not necessarily terribly full of people all the time. They just sprawl quite extensively.

They sprawl in ways that I think the edges of the city still look somewhat like the center of the city, which there’s too many high-rises. There’s probably fewer parks. There’s probably fewer restaurants. Almost nobody has a yard and a dog in their home. That’s in part because the Communist Party has organized most people to live in apartment compounds in which it is much easier to control them.

We saw this really extensively in the pandemic, in which people were unable to leave their Shanghai apartment compounds for anything other than getting their noses and mouths swabbed. I write a little bit about how, if you take the rail outside of major cities like Beijing and Shanghai, you hit farmland really, really quickly. That is in part because the Communist Party assesses governors as well as mayors on their degree of food self-sufficiency.

Cities like Shanghai and Beijing have to produce a lot of their own crops, both grains as well as vegetables, as well as fruits, as well as livestock, within a certain radius so that in case there’s ever a major devastating war, they don’t have to rely on strawberries from Mexico or strawberries from Cambodia, or Thailand. There’s a lot of farmland allocated outside of major cities. I think that will prevent suburban sprawl. You can’t control people if they all have a yard as well as a dog. I think the Communist Party will not allow it.

COWEN: Whether the variable of engineers matters, I went and I looked at the history of other East Asian economies, which have done very well in manufacturing, built out generally excellent infrastructure. None of these problems with the Second Avenue line in New York. Taiwan, like the presidents, at least if we believe GPT-5, three of them were lawyers and none of them were engineers. South Korea, you have actually some economists, a lot of bureaucrats.

WANG: Wow. Imagine that. Economists in charge, Tyler.

COWEN: I wouldn’t think it could work. A few lawyers, one engineer. Singapore, Lee Kuan Yew, he’s a lawyer. He thinks in a very lawyerly manner. Singapore has arguably done the best of all those countries. Much richer than China, inspired China. Why should I think engineers rather than just East Asia, and a bunch of other accompanying facts about these places are what matter?

WANG: Japan, a lot of lawyers in the top leadership. What exactly was the leadership of Hong Kong? A bunch of British civil servants.

COWEN: Some of whom are probably lawyers or legal-type minds, right? Not in general engineers.

WANG: PPE grads. I think that we can understand the engineering variable mostly because of how much more China has done relative to Japan and South Korea and Taiwan.

COWEN: It’s much, much poorer. Per capita manufacturing output is gone much better in these other countries.

And:

WANG: Tyler, what does it say about us that you and I have generally a lot of similar interests in terms of, let’s call it books, music, all sorts of things, but when it comes to particular categories of things, we oppose each other diametrically. I much prefer Anna Karenina to War and Peace. I prefer Buddenbrooks to Magic Mountain. Here again, you oppose me. What’s the deal?

COWEN: I don’t think the differences are that big. For instance, if we ask ourselves, what’s the relative ranking of Chengdu plus Chongqing compared to the rest of the world? We’re 98.5% in agreement compared to almost anyone else. When you get to the micro level, the so-called narcissism of petty differences, obviously, you’re born in China. I grew up in New Jersey. It’s going to shape our perspectives.

Anything in China, you have been there in a much more full-time way, and you speak and read Chinese, and none of that applies to me. I’m popping in and out as a tourist. Then, I think the differences make much more sense. It’s possible I would prefer to live in Shanghai for essentially the reasons you mentioned. If I’m somewhere for a week, I’m definitely going to pick Beijing. I’ll go around to the galleries. The things that are terrible about the city just don’t bother me that much, because I know I’ll be gone.

WANG: 98.5% agreement. I’ll take that, Tyler. It’s you and me against the rest of the world, but then we’ll save our best disagreements for each other.

COWEN: Let’s see if you can pass an intellectual Turing test. Why is it that I think Yunnan is the single best place in the world to visit? Just flat out the best if you had to pick one region. Not why you think it is, but why I think it is.

Strongly recommended, Dan and I had so much fun we kept going for about an hour and forty minutes. And of course you should buy and read Dan’s bestselling book Breakneck: China’s Quest to Engineer the Future.

Best movies of 2025

This was one of the weakest years in my lifetime for movies, and with few that would count as truly great. Here are the ones I liked:

Soundtrack for a Coup d’Etat

Flow

I’m Still Here

On Becoming a Guinea Fowl

Gazer

The Shrouds

Warfare

Oh, Hi

Weapons

Sorry, Baby

Red Rooms (actually 2023 but it deserves a mention anyway)

Hamnet

The Materialists

The Thinking Game

The Secret Agent

What else? I am still waiting for various foreign films to be available online, that will make this list stronger.

*The Age of Disclosure*

I have now watched the whole movie. The first twenty-eight minutes are truly excellent, the best statement of the case for taking UAPs seriously. It is impressive how they lined up dozens of serious figures, from the military and intelligence services, willing to insist that UAPs are a real phenomenon, supported by multiple sources of evidence. Not sensor errors, not flocks of birds, and not mistakes in interpreting images. This part of the debate now should be considered closed. It is also amazing that Marco Rubio has such a large presence in the film, as of course he is now America’s Secretary of State.

You will note this earlier part of the movie does not insist that UAPs are aliens.

After that point, the film runs a lot of risks. About one-third of what is left is responsible, along the lines of the first twenty-eight minutes. But the other two-thirds or so consists of quite unsupported claims about alien beings, bodies discovered, reverse engineering, quantum bubbles, and so on. You will not find dozens of respected, credentialed, obviously non-crazy sources confirming any of those propositions. The presentation also becomes too conspiratorial. Still, part of the latter part of the movie remains good and responsible.

Overall I can recommend this as an informative and sometimes revelatory compendium of information. It does not have anything fundamentally new, but brings together the evidence in the aggregate better than any other source I know,and it assembles the best and most credible set of testifiers. And then there are the irresponsible bits, which you can either ignore (though still think about), or use as a reason to dismiss the entire film. I will do the former.

The Game Theory of House of Dynamite

In the comments to yesterday’s review of House of Dynamite, some people balked at the movie’s central premise: that the U.S. has to decide—immediately—whether to launch a retaliatory nuclear strike. “Why not wait?” they asked. “Why not take a few days, even a few months, to figure out who actually fired the missile?”

That question even came up at GMU lunch, so it’s worth explaining why the time pressure is realistic. No real spoilers.

The U.S. doesn’t know whether the missile came from China, Russia, or North Korea and that seems to weigh in favor of waiting and gathering evidence. But here’s the problem: Russia, China, and North Korea don’t know what the U.S. knows. Suppose Russia thinks the U.S. believes Russia launched the strike. Then Russia expects retaliation. Expecting retaliation makes it rational for Russia to attack first. So Russia mobilizes.

The mobilization convinces the U.S. that Russia is preparing to attack—so now it’s rational for the U.S. to strike first. Which, of course, confirms Russia’s fears and pushes them closer to launching.

Even if the U.S. doesn’t actually think Russia fired the missile, it might still attack. Why? Because it believes that Russia believes the U.S. believes Russia did.

In this belief spiral, delay brings doom not clarity. In the film, Jake Baerington tries to break the doom loop but the logic is strong and amplified by speed and fear. Breaking the loop isn’t impossible, but as the movie suggests, it requires an act that cuts against immediate self-interest.

What to Watch

A House of Dynamite (Netflix) is an expertly crafted political thriller about living 18 minutes from nuclear annihilation. Directed by Kathryn Bigelow, it shares thematic DNA with two of her previous films, The Hurt Locker and Zero Dark Thirty. (Bigelow also directed the cult classic Point Break and the underrated Strange Days). The film tightens the tension in the first 18 minutes, releases it just enough to breathe, then resets and winds you up again—and then again. There is no climax. That frustrates some viewers, but the ending makes the point: the film is fiction but we are the ones living in a house of dynamite. Nuclear war is underrated as a problem–see previous MR posts. The film is technically and politically well researched, which is one reason the Pentagon is trying to pushback on some figures. If HOD is to be charged with a lack of realism, it’s in the competency of the within 18-minute response (although there are some excellent phone scenes.)

Springsteen: Deliver Me from Nowhere isn’t a conventional rock biopic. It focuses on the making of Nebraska, Springsteen’s bleakest and most intimate album—a solo acoustic recorded at his home in New Jersey on a cassette. Nebraska’s songs portray not the merely unlucky, but the damned: people who drag others down with them.

I saw her standing on her front lawn

Just a-twirling her baton

Me and her went for a ride, sir

And ten innocent people died…I can’t say that I’m sorry

For the things that we done

At least for a little while, sir

Me and her, we had us some fun

Springsteen was depressed at the time. The film has three love stories, the first and least important is between Springsteen and his then girlfriend. The second is Springsteen’s relationship with his troubled father. The third is with his manager, Jon Landau. We should all be so lucky to have someone who loves us as much as Landau loved Springsteen.

Jeremy Allen White, as Springsteen, gives a strong performance; in some shots he looks uncannily like him. He sings most of the songs himself and excels on the Nebraska material, though he can’t match Springsteen’s power and electricity on the brief E Street Band sequences. Jeremy Strong is excellent as Landau.

I liked Deliver Me from Nowhere, but it doesn’t demand a big screen, you can watch at home.

It’s not a movie, but for my money Wings for Wheels: The Making of “Born to Run”, included with the 30th-anniversary edition of BTR, remains the definitive portrait of Springsteen at work. It shows Springsteen driving the E Street Band through take after take, unrelenting and exhausting, in pursuit of the sound in his head—a great study in creative obsession. Pairs well with the very different process documented in Peter Jackson’s Get Back.

Red Rooms, a 2023 Quebecois movie

Highly disturbing, so I do not recommend it to most of you. It concerns a murder trial, and while violence is never shown on screen it is harrowing to watch. Much of the movie is about the spectators at the trial, and you can think of it as one vision for how online life will evolve for a particular class of people. Even in 2023, the movie had “LLM psychosis” as a subtheme. Grossly underrated, so I am passing this information along, which originally comes from Eugene. Here is the Wikipedia page, here is the trailer.

No one applauded, I remain optimistic about democracy

*One Battle After Another*

That is the new Paul Thomas Anderson movie, inspired by Pynchon’s Vineland. I do not usually like Anderson’s films (apart from Magnolia), but this so far is the best movie of the year? It takes the “Days of Rage” themes and connects them to our current predicament, weaving them into a unified whole, where the world has some characteristics of the 1970s and some of today. Some scenes are flawed, but overall the cast, soundtrack, and cinematography are the best I have seen in some while. We are doing cinema again, or at least he is. Recommended, noting that it can be dispiriting and difficult to watch. Here is the Yglesias review.

My excellent Conversation with Steven Pinker

Here is the audio, video, and transcript. Here is part of the episode summary:

Tyler and Steven probe these dimensions of common knowledge—Schelling points, differential knowledge, benign hypocrisies like a whisky bottle in a paper bag—before testing whether rational people can actually agree (spoiler: they can’t converge on Hitchcock rankings despite Aumann’s theorem), whether liberal enlightenment will reignite and why, what stirring liberal thinkers exist under the age 55, why only a quarter of Harvard students deserve A’s, how large language models implicitly use linguistic insights while ignoring linguistic theory, his favorite track on Rubber Soul, what he’ll do next, and more.

Excerpt:

COWEN: Surely there’s a difference between coordination and common knowledge. I think of common knowledge as an extremely recursive model that typically has an infinite number of loops. Most of the coordination that goes on in the real world is not like that. If I approach a traffic circle in Northern Virginia, I look at the other person, we trade glances. There’s a slight amount of recursion, but I doubt if it’s ever three loops. Maybe it’s one or two.

We also have to slow down our speeds precisely because there are not an infinite number of loops. We coordinate. What percentage of the coordination in the real world is like the traffic circle example or other examples, and what percentage of it is due to actual common knowledge?

PINKER: Common knowledge, in the technical sense, does involve this infinite number of arbitrarily embedded beliefs about beliefs about beliefs. Thank you for introducing the title with the three dots, dot, dot, dot, because that’s what signals that common knowledge is not just when everyone knows that everyone knows, but when everyone knows that everyone knows that and so on. The answer to your puzzle — and I devote a chapter in the book to what common knowledge — could actually consist of, and I’m a psychologist, I’m not an economist, a mathematician, a game theorist, so foremost in my mind is what’s going on in someone’s head when they have common knowledge.

You’re right. We couldn’t think through an infinite number of “I know that he knows” thoughts, and our mind starts to spin when we do three or four. Instead, common knowledge can be generated by something that is self-evident, that is conspicuous, that’s salient, that you can witness at the same time that you witness other people witnessing it and witnessing you witnessing it. That can grant common knowledge in a stroke. Now, it’s implicit common knowledge.

One way of putting it is you have reason to believe that he knows that I know that he knows that I know that he knows, et cetera, even if you don’t literally believe it in the sense that that thought is consciously running through your mind. I think there’s a lot of interplay in human life between this recursive mentalizing, that is, thinking about other people thinking about other people, and the intuitive sense that something is out there, and therefore people do know that other people know it, even if you don’t have to consciously work that through.

You gave the example of norms and laws, like who yields at an intersection. The eye contact, though, is crucial because I suggest that eye contact is an instant common knowledge generator. You’re looking at the part of the person looking at the part of you, looking at the part of them. You’ve got instant granting of common knowledge by the mere fact of making eye contact, which is why it’s so potent in human interaction and often in other species as well, where eye contact can be a potent signal.

There are even species that can coordinate without literally having common knowledge. I give the example of the lowly coral, which presumably not only has no beliefs, but doesn’t even have a brain with which to have beliefs. Coral have a coordination problem. They’re stuck to the ocean floor. Their sperm have to meet another coral’s eggs and vice versa. They can’t spew eggs and sperm into the water 24/7. It would just be too metabolically expensive. What they do is they coordinate on the full moon.

On the full moon or, depending on the species, a fixed number of days after the full moon, that’s the day where they all release their gametes into the water, which can then find each other. Of course, they don’t have common knowledge in knowing that the other will know. It’s implicit in the logic of their solution to a coordination problem, namely, the public signal of the full moon, which, over evolutionary time, it’s guaranteed that each of them can sense it at the same time.

Indeed, in the case of humans, we might do things that are like coral. That is, there’s some signal that just leads us to coordinate without thinking it through. The thing about humans is that because we do have or can have recursive mentalizing, it’s not just one signal, one response, full moon, shoot your wad. There’s no limit to the number of things that we can coordinate creatively in evolutionarily novel ways by setting up new conventions that allow us to coordinate.

COWEN: I’m not doubting that we coordinate. My worry is that common knowledge models have too many knife-edge properties. Whether or not there are timing frictions, whether or not there are differential interpretations of what’s going on, whether or not there’s an infinite number of messages or just an arbitrarily large number of messages, all those can matter a lot in the model. Yet actual coordination isn’t that fragile. Isn’t the common knowledge model a bad way to figure out how coordination comes about?

And this part might please Scott Sumner:

COWEN: I don’t like most ballet, but I admit I ought to. I just don’t have the time to learn enough to appreciate it. Take Alfred Hitchcock. I would say North by Northwest, while a fine film, is really considerably below Rear Window and Vertigo. Will you agree with me on that?

PINKER: I don’t agree with you on that.

COWEN: Or you think I’m not your epistemic peer on Hitchcock films?

PINKER: Your preferences are presumably different from beliefs.

COWEN: No. Quality relative to constructed standards of the canon…

COWEN: You’re going to budge now, and you’re going to agree that I’m right. We’re not doing too well on this Aumann thing, are we?

PINKER: We aren’t.

COWEN: Because I’m going to insist North by Northwest, again, while a very good movie is clearly below the other two.

PINKER: You’re going to insist, yes.

COWEN: I’m going to insist, and I thought that you might not agree with this, but I’m still convinced that if we had enough time, I could convince you. Hearing that from me, you should accede to the judgment.

I was very pleased to have read Steven’s new book