Category: Current Affairs

My very fun Conversation with Blake Scholl

Here is the audio, video, and transcript. This was at a live event (the excellent Roots of Progress conference), so it is only about forty minutes, shorter than usual. Here is the episode summary:

Blake Scholl is one of the leading figures working to bring back civilian supersonic flight. As the founder and CEO of Boom Supersonic, he’s building a new generation of supersonic aircraft and pushing for the policies needed to make commercial supersonic travel viable again. But he’s equally as impressive as someone who thinks systematically about improving dysfunction—whether it’s airport design, traffic congestion, or defense procurement—and sees creative solutions to problems everyone else has learned to accept.

Tyler and Blake discuss why airport terminals should be underground, why every road needs a toll, what’s wrong with how we board planes, the contrasting cultures of Amazon and Groupon, why Concorde and Apollo were impressive tech demos but terrible products, what Ayn Rand understood about supersonic transport in 1957, what’s wrong with aerospace manufacturing, his heuristic when confronting evident stupidity, his technique for mastering new domains, how LLMs are revolutionizing regulatory paperwork, and much more.

Excerpt:

COWEN: There’s plenty about Boom online and in your interviews, so I’d like to take some different tacks here. This general notion of having things move more quickly, I’m a big fan of that. Do you have a plan for how we could make moving through an airport happen more quickly? You’re in charge. You’re the dictator. You don’t have to worry about bureaucratic obstacles. You just do it.

SCHOLL: I think about this in the shower like every day. There is a much better airport design that, as best I can tell, has never been built. Here’s the idea: You should put the terminals underground. Airside is above ground. Terminals are below ground. Imagine a design with two runways. There’s an arrival runway, departure runway. Traffic flows from arrival runway to departure runway. You don’t need tugs. You can delete a whole bunch of airport infrastructure.

Imagine you pull into a gate. The jetway is actually an escalator that comes up from underneath the ground. Then you pull forward, so you can delete a whole bunch of claptrap that is just unnecessary. The terminal underground should have skylights so it can still be incredibly beautiful. If you model fundamentally the thing on a crossbar switch, there are a whole bunch of insights for how to make it radically more efficient. Sorry. This is a blog post I want to write one day. Actually, it’s an airport I want to build.

And;

COWEN: I’m at the United desk. I have some kind of question. There’s only two or three people in front of me, but it takes forever. I notice they’re just talking back and forth to the assistant. They’re discussing the weather or the future prospects for progress, total factor productivity. I don’t know. I’m frustrated. How can we make that process faster? What’s going wrong there?

SCHOLL: The thing I most don’t understand is why it requires so many keystrokes to check into a hotel room. What are they writing?

What are they writing?

Mexico facts of the day

I have been expecting this for a long time, but it came more quickly than I thought:

Mexico is now the world’s top buyer of U.S. goods, according to data released by the U.S. government on Wednesday, outpacing Canada for the first time in nearly 30 years.

The data highlighted how Mexico and the United States have, despite periodic political tensions, become deeply intertwined in business, and how much global trade patterns have shifted in a short period. Only two years ago, Mexico became the country that sold the most goods to the United States, surpassing China.

“Mexico is the United States’ main trading partner,” said Marcelo Ebrard, Mexico’s economy minister, during the president’s daily news conference on Wednesday.

Here is more from the NYT. Via Brian Winter. As I have been telling people for decades now, visiting Mexico, learning about Mexico, and learning Spanish are very good investments in understanding the world, most of all if you live in the USA.

American democracy is very much alive, though not in all regards well

The Democrats who won in the November elections are all going to assume office without incident or controversy.

The Supreme Court is likely to rule against at least major parts of the Trump tariff plan, his signature initiative. Trump already has complained vocally on social media about this. He also preemptively announced that some of the food tariffs would be reversed, in the interests of “affordability.”

National Guard troops have been removed from Chicago and Portland, in part due to court challenges. The troops in WDC have turned out to be a nothingburger from a civil liberties point of view.

Here is an account of November 18 and all that happened that day:

* House votes 427-1 to release the Epstein files, a veto-proof+ majority

* A federal judge blocked GOP redistricting map in Texas, meaning net net with CA measure passed, Democrats could pick up seats for 2026, KARMA!

* A federal appeals court, including two Trump appointed judges, rejected Trump’s defamation lawsuit against CNN over the term “Big Lie,” finding the case meritless

* Corporate Public Broadcasting agree to fulfill its $36 million annual contract with NPR, after a judge told Trump appointees at CPB that their defense was not credible

* A NY judge dismissed Trump’s calling of New York’s law barring immigration arrests in state and local courthouses.

The Senate also sided with the House on the Epstein files. Nate Silver and many others write about how Trump is now quite possibly a lame duck President.

I do not doubt that there are many bad policies, and also much more corruption, and a more transparent form of corruption, which is corrosive in its own right. But it was never the case that American democracy was going to disappear. That view was one of the biggest boo-boos held by (some) American elites in recent times, and I hope we will start seeing people repudiating it.

I think the causes of this error have been:

1. Extreme dislike of the Trump administration, leading to emotional reactions when a bit more analysis would have done better.

2. Pessimism bias in the general sense.

3. Recency bias — for the earlier part of the term, Congress was relatively quiescent.

4. Cognitive and emotional inability to admit the simple truth of “democracy itself can lead to pretty bad outcomes,” thus the need to paint the status quo as something other than democracy.

5. The (largely incorrect) theory of good things happening in politics is “good people will them,” so from that starting point if you see bad people willing bad things you freak out. The understanding was never “spontaneous order” enough to begin with.

Any other?

The MR Podcast: Tariffs!

On The Marginal Revolution Podcast this week, Tyler and I discuss tariffs! Here’s one bit:

COWEN: I have a new best argument against tariffs. It’s very soft. I think it’s hard to prove, but it might actually be the very best argument against tariffs.

TABARROK: All right, let’s hear it.

COWEN: If you think about COVID policy, the wealthy nations did a bunch of things. Some of them were quite bad, and the poorer nations all copied that. They didn’t have to copy it, but there was some kind of contagion effect, or that seemed like the high-status thing to do. I believe with tariffs, something similar goes on. There’s a huge literature about retaliation. Of course, retaliation is a cost, that’s bad, but simply the copying effect that it was high status for the wealthy nations to have tariffs. They can afford it better, but then places like India had their own version of the same thing. That was just terrible for India at a much higher human cost than, say, it was for the United States. Again, it’s hard to trace or prove, but that I think could actually be the best argument against tariffs, simply that poorer countries will copy what the high-status nations are doing.

This is like Rob Henderson’s idea of luxury beliefs, beliefs which the elite can proffer at low cost but which have negative consequences when adopted by working and lower classes. Tariffs aren’t great for the US but the US is so large and rich we can handle it but if the idea is adopted by poorer nations it will be much worse for them. I wish I had been clever enough to say this during the podcast but I never know what Tyler will say in advance.

Here’s another bit:

TABARROK: Here’s the question which the Trumpers or other people never really answer is, what are we going to have less of? Yes, we’ll have more investment. Let’s say we get another auto plant. The unemployment rate is 4%, so it’s not like we have a lot of free resources around. Most of the time, we’re in full equilibrium. If we have more auto plant workers and more cars being produced in the United States, we’re going to have less of something. I think it is incumbent on people who want tariffs in order to get more employment in manufacturing or something like that to say, “Well, what are we going to have less of?”

COWEN: The more sophisticated ones of them, I think, would say, well, the US is super high on the consumption scale, even relative to our very high per capita incomes. If we end up spending some of that consumption on boosting real wages, it’s actually a good investment, if only in political sanity, stability, fewer opioid deaths. It’s a very indirect chain of reasoning. I would say I’m skeptical. Again, it’s not a crazy argument. It’s a weird kind of industrial policy where you channel resources away from consumption into investment and higher wages. A lot of those plants are automated. They’re going to be automated much yet. It’s further stuff, maybe to other robotics companies or the AI companies. Again, I think that’s what they would say.

TABARROK: I don’t think they would say that.

COWEN: No, the more sophisticated ones.

TABARROK: Are there? I haven’t seen too many of those….

Here’s the episode. Subscribe now to take a small step toward a much better world: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | YouTube.

Waymo

Waymo now does highways in the Bay area.

Expanding our service territory in the Bay Area and introducing freeways is built on real-world performance and millions of miles logged on freeways, skillfully handling highway dynamics with our employees and guests in Phoenix, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. This experience, reinforced by comprehensive testing as well as extensive operational preparation, supports the delivery of a safe and reliable service.

The future is happening fast.

Prediction markets in everything? Tariff refund edition

Oppenheimer changed its terms from offers earlier this year. The firm said it would consider bids starting at 20 percent per refund claim pertaining to “reciprocal” or IEEPA tariffs and 10 percent for tariffs tied to fentanyl.

Gabriel Rodriguez, the president and co-founder of A Customs Brokerage, in Doral, Fla., and a recipient of several emails from Oppenheimer, said he believed Oppenheimer was offering to pay the equivalent of 80 cents on the dollar per claim.

Here is more from the NYT, via Amy.

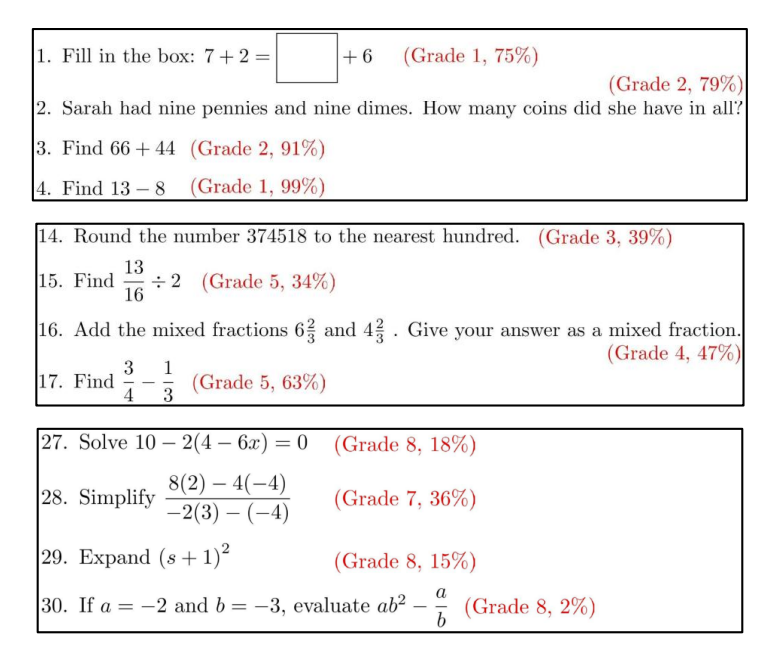

UCSD Faculty Sound Alarm on Declining Student Skills

The UC San Diego Senate Report on Admissions documents a sharp decline in students’ math and reading skills—a warning that has been sounded before, but this time it’s coming from within the building.

At our campus, the picture is truly troubling. Between 2020 and 2025, the number of freshmen whose math placement exam results indicate they do not meet middle school standards grew nearly thirtyfold, despite almost all of these students having taken beyond the minimum UCOP required math curriculum, and many with high grades. In the 2025 incoming class, this group constitutes roughly one-eighth of our entire entering cohort. A similarly large share of students must take additional writing courses to reach the level expected of high school graduates, though this is a figure that has not varied much over the same time span.

Moreover, weaknesses in math and language tend to be more related in recent years. In 2024, two out of five students with severe deficiencies in math also required remedial writing instruction. Conversely, one in four students with inadequate writing skills also needed additional math preparation.

The math department created a remedial course, only to be so stunned by how little the students knew that the class had to be redesigned to cover material normally taught in grades 1 through 8.

Alarmingly, the instructors running the 2023-2024 Math 2 courses observed a marked change in the skill gaps compared to prior years. While Math 2 was designed in 2016 to remediate missing high school math knowledge, now most students had knowledge gaps that went back much further, to middle and even elementary school. To address the large number of underprepared students, the Mathematics Department redesigned Math 2 for Fall 2024 to focus entirely on elementary and middle school Common Core math subjects (grades 1-8), and introduced a new course, Math 3B, so as to cover missing high-school common core math subjects (Algebra I, Geometry, Algebra II or Math I, II, III; grades 9-11).

In Fall 2024, the numbers of students placing into Math 2 and 3B surged further, with over 900 students in the combined Math 2 and 3B population, representing an alarming 12.5% of the incoming first-year class (compared to under 1% of the first-year students testing into these courses prior to 2021)

(The figure gives some examples of remedial class material and the percentage of remedial students getting the answers correct.)

The report attributes the decline to several factors: the pandemic, the elimination of standardized testing—which has forced UCSD to rely on increasingly inflated and therefore useless high school grades—and political pressure from state lawmakers to admit more “low-income students and students from underrepresented minority groups.”

…This situation goes to the heart of the present conundrum: in order to holistically admit a diverse and representative class, we need to admit students who may be at a higher risk of not succeeding (e.g. with lower retention rates, higher DFW rates, and longer time-to-degree).

The report exposes a hard truth: expanding access without preserving standards risks the very idea of a higher education. Can the cultivation of excellence survive an egalitarian world?

Solve for the NIMBY equilibrium?

We are just beginning to think these issues through:

The government’s plan to use artificial intelligence to accelerate planning for new homes may be about to hit an unexpected roadblock: AI-powered nimbyism.

A new service called Objector is offering “policy-backed objections in minutes” to people who are upset about planning applications near their homes.

It uses generative AI to scan planning applications and check for grounds for objection, ranking these as “high”, “medium” or “low” impact. It then automatically creates objection letters, AI-written speeches to deliver to the planning committees, and even AI-generated videos to “influence councillors”.

Kent residents Hannah and Paul George designed the system after estimating they spent hundreds of hours attempting to navigate the planning process when they opposed plans to convert a building near their home into a mosque.

Here is the full story. Via Aaron K.

Mexico estimates of the day

Ms Sheinbaum’s government says Mexico’s murder rate has come down by 32% in the year since she took office. Analysis by The Economist confirms that the rate has fallen, though by a significantly smaller margin, 14%. Counting homicides alone misses an important part of the picture, namely the thousands of people who disappear in Mexico every year, many of whom are killed and buried in unmarked graves. A broader view of deadly crime that includes manslaughter, femicide and two-thirds of disappearances (the data for disappearances is imperfect), shows a more modest decline of 6% (see chart). Still, Mexico is on track for about 24,300 murders this year, horribly high, but well below the recent annual average of slightly over 30,000. Ms Sheinbaum is the first Mexican leader in years to push violent crime in the right direction.

Here is more from The Economist.

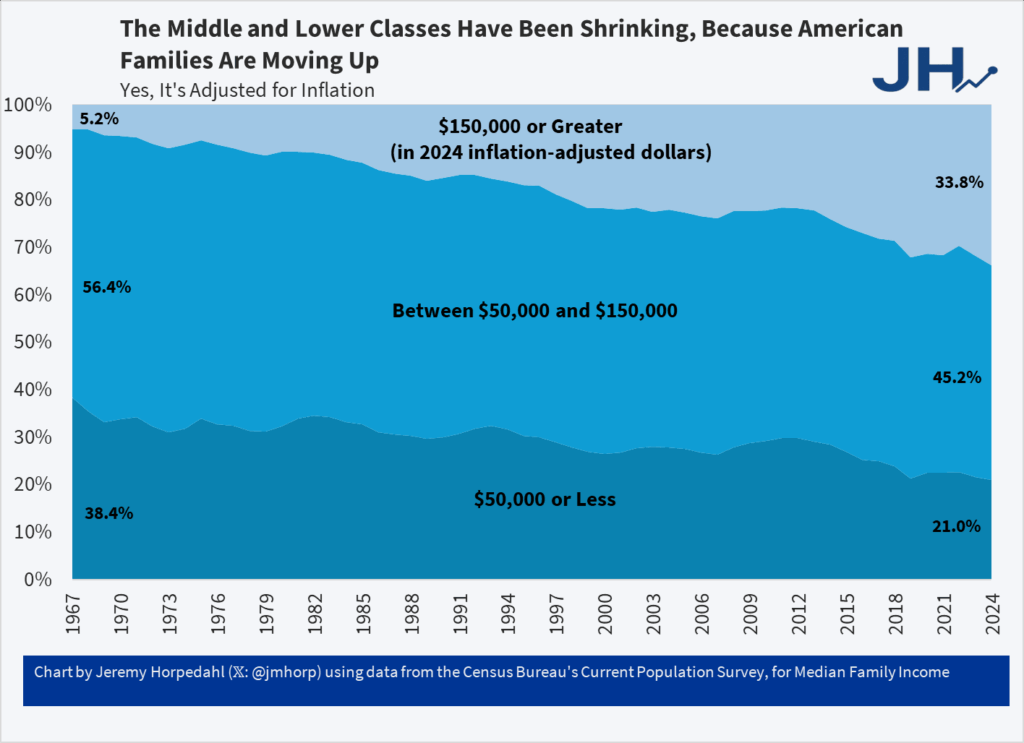

One-Third of US Families Earn Over $150,000

It’s astonishing that the richest country in world history could convince itself that it was plundered by immigrants and trade. Truly astonishing.

From Jeremy Horpedahl who notes:

This is from the latest Census release of CPS ASEC data, updated through 2024 (see Table F-23 at this link).

In 1967, only 5 percent of US families earned over $150,000 (inflation adjusted).

And even though it says so in the chart and in the text let me say it again, this is inflation adjusted and so yes it’s real and no the fact that housing has gone up in price doesn’t negate this, it’s built in. We would have done even better had NIMBYs not reduced the supply of housing.

See also Asness and Strain.

Addendum: Note it isn’t the rise of dual-earner households which haven’t increased for over 30 years.

Affordability sentences to ponder

Creative Stagnation

Legislation requiring cars and trucks, including electric vehicles, to have AM radios easily cleared a House committee Wednesday, although it could run into opposition going forward.

H.R. 979, the “AM Radio for Every Vehicle Act,” would require the Department of Transportation to enforce the mandate through a rulemaking. It passed the Energy and Commerce Committee by a 50-1 vote. Rep. Jay Obernolte (R-Calif.) was the only “no.”

What’s next—mandating 8-track players in every car? Fax machines in every home? Floppy disks in every laptop? If Congress actually cared about emergency communication, it would strengthen cellular networks, not cling to obsolete technology. Congress is a den of old busybodies.

Hat tip: Nick Gillespie.

Addendum: If AM radio is so valuable for emergencies then the market will provide or you could, you know, put an AM radio in your glove box. No need for a mandate. We already have FM, broadcast TV, cable, satellite, cell, and Wireless Emergency Alerts; resilience can be met without specifying AM hardware.

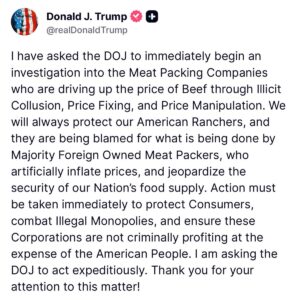

I worry about “affordability politics”

It focuses the listener’s attention on price rather than quantity. To many people it sounds better than “economic growth,” though often for the wrong reasons. I cover related points in my latest Free Press article:

Rather than suggesting beneficial economic reforms, the affordability mantra too often leads to “free lunch” thinking and political giveaways. It is a new form of economic populism—a more general rubric of which, after the volatility and disruptions of the Trump tariffs, I have had enough.

I am not opposed to “affordability” as an abstract concept. For instance, I find food prices shockingly high, even in so-so restaurants, and I wish the prices were lower. And if I were in charge of the economy, I would try to lower costs. But there are only so many ways to do that. One option would be to deregulate the energy sector, easing permitting for solar, wind, and nuclear power. Over a five- to 10-year time horizon, that would lead to cheaper energy and, indirectly, to modestly lower food prices. I would also repeal the Trump tariffs, which artificially inflate the cost of foreign goods. I might also refrain from minimum wage increases, which only cause the price of food to rise further.

But even in the best-case scenario, all of those actions would make food just a bit cheaper than it would be otherwise. I would hardly expect voters to hail my reign as a major triumph, or ask for more of the same. Instead, they might flock to the candidate who promises government-run grocery stores or price controls. Sound familiar?

I do not expect this problem to go away anytime soon, and now it is the Trump people too.

UATX Is Ending Tuition Forever

Thanks to a $100 million gift from Jeff Yass — the largest donation since UATX was founded in 2021 — we’re breaking the chains. His gift marks the launch of a $300 million campaign to build a university that sets students free.

Our bet: Create graduates so exceptional they’ll pay it forward when they succeed, financing the tuition of the next generation. When our students build important companies, defend our nation, advance scientific frontiers, build families, and create works that elicit awe, they’ll remember who made their excellence possible. And they’ll give back.

Here is the full announcement.

My excellent Conversation with Sam Altman

Recorded live in Berkeley, at the Roots of Progress conference (an amazing event), here is the material with transcript, here is the episode summary:

Sam Altman makes his second appearance on the show to discuss how he’s managing OpenAI’s explosive growth, what he’s learned about hiring hardware people, what makes roon special, how far they are from an AI-driven replacement to Slack, what GPT-6 might enable for scientific research, when we’ll see entire divisions of companies run mostly by AI, what he looks for in hires to gauge their AI-resistance, how OpenAI is thinking about commerce, whether GPT-6 will write great poetry, why energy is the binding constraint to chip-building and where it’ll come from, his updated plan for how he’d revitalize St. Louis, why he’s not worried about teaching normies to use AI, what will happen to the price of healthcare and hosing, his evolving views on freedom of expression, why accidental AI persuasion worries him more than intentional takeover, the question he posed to the Dalai Lama about superintelligence, and more.

Excerpt:

COWEN: What is it about GPT-6 that makes that special to you?

ALTMAN: If GPT-3 was the first moment where you saw a glimmer of something that felt like the spiritual Turing test getting passed, GPT-5 is the first moment where you see a glimmer of AI doing new science. It’s very tiny things, but here and there someone’s posting like, “Oh, it figured this thing out,” or “Oh, it came up with this new idea,” or “Oh, it was a useful collaborator on this paper.” There is a chance that GPT-6 will be a GPT-3 to 4-like leap that happened for Turing test-like stuff for science, where 5 has these tiny glimmers and 6 can really do it.

COWEN: Let’s say I run a science lab, and I know GPT-6 is coming. What should I be doing now to prepare for that?

ALTMAN: It’s always a very hard question. Even if you know this thing is coming, if you adapt your —

COWEN: Let’s say I even had it now, right? What exactly would I do the next morning?

ALTMAN: I guess the first thing you would do is just type in the current research questions you’re struggling with, and maybe it’ll say, “Here’s an idea,” or “Run this experiment,” or “Go do this other thing.”

COWEN: If I’m thinking about restructuring an entire organization to have GPT-6 or 7 or whatever at the center of it, what is it I should be doing organizationally, rather than just having all my top people use it as add-ons to their current stock of knowledge?

ALTMAN: I’ve thought about this more for the context of companies than scientists, just because I understand that better. I think it’s a very important question. Right now, I have met some orgs that are really saying, “Okay, we’re going to adopt AI and let AI do this.” I’m very interested in this, because shame on me if OpenAI is not the first big company run by an AI CEO, right?

COWEN: Just parts of it. Not the whole thing.

ALTMAN: No, the whole thing.

COWEN: That’s very ambitious. Just the finance department, whatever.

ALTMAN: Well, but eventually it should get to the whole thing, right? So we can use this and then try to work backwards from that. I find this a very interesting thought experiment of what would have to happen for an AI CEO to be able to do a much better job of running OpenAI than me, which clearly will happen someday. How can we accelerate that? What’s in the way of that? I have found that to be a super useful thought experiment for how we design our org over time and what the other pieces and roadblocks will be. I assume someone running a science lab should try to think the same way, and they’ll come to different conclusions.

COWEN: How far off do you think it is that just, say, one division of OpenAI is 85 percent run by AIs?

ALTMAN: Any single division?

COWEN: Not a tiny, insignificant division, mostly run by the AIs.

ALTMAN: Some small single-digit number of years, not very far. When do you think I can be like, “Okay, Mr. AI CEO, you take over”?

Of course we discuss roon as well, not to mention life on the moons of Saturn…