Category: Current Affairs

Housing 101

John Arnold points us to this table on new apartments and pointedly notes that the population of LA (18.5 m) is more than 7 times that of Austin (2.5m).

MR readers will not be surprised to learn that apartment prices are falling in Austin.

Meanwhile the WSJ reports another shocker, New York’s Airbnb Crackdown, in Force for Two Years, Hasn’t Improved Housing Supply. But guess what has happened? Ok, you don’t have to guess. Hotel prices have increased:

Hotels tend to benefit from tighter Airbnb restrictions, especially in New York City. Significantly reducing the number of apartments that can be rented for less than 30 days undeniably boosts demand for hotel rooms in a city visited by tens of millions of tourists a year.

Without the law, “we would be in a catastrophic situation,” said hotelier Richard Born, who owns 24 hotels across the city.

France fact of the day

If nothing is done, interest payments will become the biggest expense in the French budget in four years, Mr. Bayrou has warned.

Here is the full NYT article, noting that government spending is 57 percent of the economy and the French have the longest financed retirements ever seen in the history of the world.

Moving on Up

James Heckman and Sadegh Eshaghnia have launched a broadside in the WSJ against the Chetty-Hendren paper The Impacts of Neighborhoods on Intergenerational Mobility I: Childhood Exposure Effects. It’s a little odd to see this in the WSJ but since the Chetty-Hendren paper has been widely reported in the media, I suppose this is fair game. Recall the basic upshot of Chetty-Hendren is that neighborhoods matter and in particular

…the outcomes of children whose families move to a better neighborhood—as measured by the outcomes of children already living there—improve linearly in proportion to the amount of time they spend growing up in that area, at a rate of approximately 4% per year of exposure.

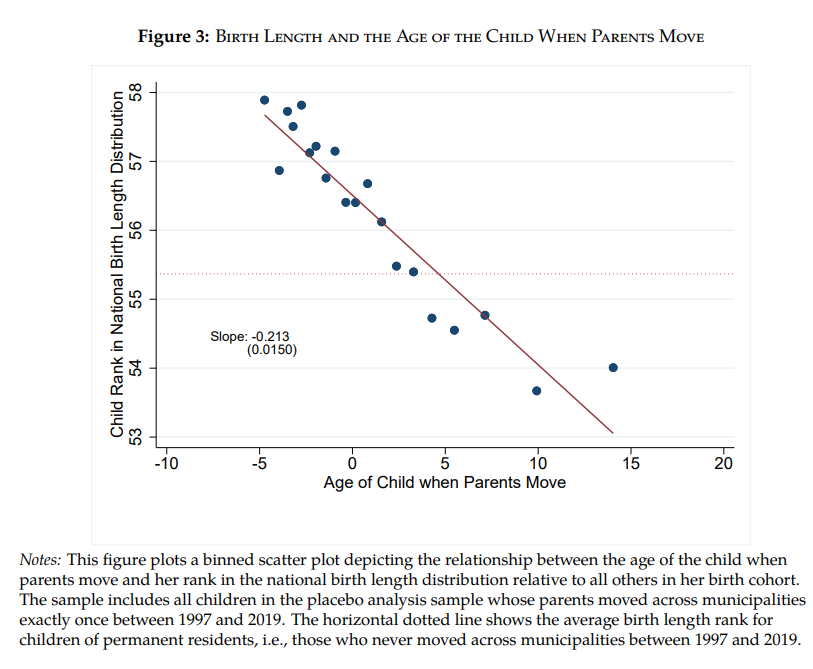

I am not going to referee this dispute but I did enjoy the audacity of one placebo test run by Eshaghnia. Eshaghnia runs the same statistical models as Chetty-Hendren but substitutes birth length (“the distance between a newborn’s head and heels”) instead of adult earnings and college attendance rates. Now, obviously, moving cannot affect birth length! Yet, Eshaghnia finds, in essence*, that children of parents who move to taller neighborhoods have taller children, in parallel with CH who find that children of parents who move to higher income neighborhoods have higher income children. Moreover, the covariance is stronger the earlier parents move. Since birth length is correlated with cognitive abilities and other later life outcomes this is highly suggestive that CH are not finding (pure) causal effects.

* I have simplified slightly for intuition. Technically, Eshaghnia shows that children’s birth‑length ranks align with the destination–origin permanent‑resident birth‑length difference, and that alignment is ≈0.044 stronger for each year earlier the move.

Addendum: Chetty et al. do not find similar results in California (see in particular Figure 2).

A few remarks on Fed independence

Trump has made various sallies against the idea of an independent Fed, including lots of rhetoric, firing Lisa Cook, aiming to have a CEA chair on the Fed board, and more. Probably the list is longer than I realize.

To be clear, I see no upside to these moves and I do not favor them. That said, I am not surprised that markets are not freaking out.

People, the Fed was never that independent to begin with!

Come 2008, the Fed, Treasury, and other parties sat down and worked out a strategy for dealing with the financial crisis. The Fed has a big voice in those decisions, but ultimately has to go along with the general agreement.

Circa, 2020-2021, with the pandemic, the same kind of procedure applied.

You may or may not like the particular decisions that were made (too little inflation the first time, too much inflation the second time), but I don’t think there is a very different way to proceed in those situations.

And given recent budgeting decisions, fiscal dominance may lie in our future in any case. The Fed is not immune from those pressures.

The Fed is most “independent” when the stakes are low and most people are happy with (more or less) two percent inflation. That is also when the independence matters least.

The real problem comes when the quality of governance is low. Then encroaching on central bank independence simply raises the level of stupidity. Some of that is happening right now.

A non-independent central bank can work just fine when the quality of government is sufficiently high. New Zealand has had a non-independent central bank since the Reserve Bank Act of 1989 (before that it had a non-independent central bank in a different and worse way). There is operational independence, but an inflation target is set in conjunction with the government. You may or may not favor this approach, but it has not been a disaster and it helped to lower Kiwi inflation rates significantly and with political cover.

Way back when, Milton Friedman used to argue periodically that Congress should set the rate of price inflation and take responsibility for it. I think that is a bad idea, especially today, but it should cure you of the notion that “independence” is sacrosanct. Every system has some means of accountability built in, and indeed has to.

I know all those scatter plot graphs that correlate central bank independence with lower inflation rates. In my view, if you could insert a true “quality of government” extra variable, the correlation mostly vanishes. Plus I do not trust the measures of independence that are used.

As Gandhi once said — “Central bank independence, it would be a good idea!”

Addendum: I also find it a little strange that many critics of the Trump actions earlier had been calling for higher inflation targets, say three or even four percent. That is maybe not an outright contradiction, but…the Fed isn’t just going to move to that on its own, right? Central bank independence for thee but not for me?

Tariff sentences to ponder

Trump’s tariff policy is an agenda for pushing American output down the value chain, away from advanced manufacturing and toward making cheaper simpler goods and supplying raw materials to China.

That is from Matt Yglesias.

Sentences to ponder

By ordering the U.S. military to summarily kill a group of people aboard what he said was a drug-smuggling boat, President Trump used the military in a way that had no clear legal precedent or basis, according to specialists in the laws of war and executive power.

Mr. Trump is claiming the power to shift maritime counterdrug efforts from law enforcement rules to wartime rules. The police arrest criminal suspects for prosecution and cannot instead simply gun suspects down, except in rare circumstances where they pose an imminent threat to someone.

Here is more from the NYT.

Oct.9th I am speaking for the Pioneer Institute in Boston, on federalism

My very interesting Conversation with Seamus Murphy

Here is the audio, video, and transcript. Here is the episode summary:

Seamus Murphy is an Irish photographer and filmmaker who has spent decades documenting life in some of the world’s most challenging places—from Taliban-controlled Afghanistan to Nigeria’s Boko Haram territories. Having left recession-era Ireland in the 1980s to teach himself photography in American darkrooms, Murphy has become that rare artist who moves seamlessly between conflict zones and recording studios, creating books of Afghan women’s poetry while directing music videos that anticipated Brexit.

Tyler and Seamus discuss the optimistic case for Afghanistan, his biggest fear when visiting any conflict zone, how photography has shaped perceptions of Afghanistan, why Russia reminded him of pre-Celtic Tiger Ireland, how the Catholic Church’s influence collapsed so suddenly in Ireland, why he left Ireland in the 1980s, what shapes Americans impression of Ireland, living part-time in Kolkata and what the future holds for that “slightly dying” but culturally vibrant city, his near-death encounters with Boko Haram in Nigeria, the visual similarities between Michigan and Russia, working with PJ Harvey on Let England Shake and their travels to Kosovo and Afghanistan together, his upcoming film about an Afghan family he’s documented for thirty years, and more.

And an excerpt:

COWEN: Now you’re living in Kolkata mainly?

MURPHY: No. I’m living in London, some of the year in Kolkata.

COWEN: Why Kolkata?

MURPHY: My wife is Indian. She grew up in Delhi, Bombay, and Kolkata, but Kolkata was her favorite. They were the years that were her most fond of years. She’s got lots of friends from Kolkata. I love the city. She was saying that if I didn’t like the city, then we wouldn’t be spending as much time in Kolkata as we do, but I do love the city.

It’s got, in many ways, everything I would look for in a city. Kabul, in a way, was a bit like Kolkata when times were better. This is maybe a replacement for Kabul for me. Kolkata is extraordinary. It’s got that history. It’s got the buildings. Bengalis are fascinating. It’s got culture, fantastic food.

COWEN: The best streets in India, right?

MURPHY: Absolutely.

COWEN: It’s my daughter’s favorite city in India.

MURPHY: Really?

COWEN: Yes.

MURPHY: What does she like about it?

COWEN: There’s a kind of noir feel to it all.

MURPHY: Absolutely.

COWEN: It’s so compelling and so strong and just grabs you, and you feel it on every street, every block. It’s probably still the most intellectual Indian city with the best bookshops, a certain public intellectual life.

MURPHY: It’s widespread. It’s not just elite. It’s everyone. We went to a huge book fair. It’s like going to . . . I don’t know what it’s like going to, Kumbh Mela or something. It’s extraordinary.

There’s a huge tent right in the middle, and it’s for what they call little magazines. Little magazines are these very small publications run by one or two people. They’ll publish poetry. They’ll publish interesting stories. Sadly, I don’t speak Bengali because I’d love to be reading this stuff. There are hundreds of these things. They survive, and people buy them. It’s not just the elite. It’s extraordinary in that way.

COWEN: Is there any significant hardship associated with living there, say a few months of the year?

MURPHY: For us, no. There’s a lot of hardship —

COWEN: No pollution?

MURPHY: Yes. The biggest pollution for me is the noise, the noise pollution.

Interesting throughout.

What should I ask Jonny Steinberg?

Yes I will be doing a Conversation with him. From Wikipedia:

Steinberg was born and raised in the northern suburbs of Johannesburg, South Africa. He was educated at Wits University in Johannesburg, and at the University of Oxford, where he was a Rhodes Scholar and earned a doctorate in political theory. He taught for nine years at Oxford, where he was Professor of African Studies. He currently teaches at Yale University‘s Council on African Studies.

Three of Steinberg’s books – Midlands (2002), about the murder of a white South African farmer, The Number (2004), a biography of a prison gangster, and Winnie & Nelson (2023) – won South Africa’s premier non-fiction prize, the Sunday Times CNA Literary Awards making him the first writer to win it three times.

I am a special fan of Winnie & Nelson, which I consider to be one of the best books of the last ten years. He is currently working on a biography of Cecil Rhodes. So what should I ask him?

The Simple Mathematics of Chinese Innovation

The NYTimes has a good data-driven piece on How China Went From Clean Energy Copycat to Global Innovator, the upshot of which is that the old view of China as simply copying (“stealing” in some eyes) no longer describes reality. In some fields, including solar, batteries and hydrogen, China is now the leading innovator as measured by high-quality patents and scientific citations.

None of this should surprise anyone. China employs roughly 2.6 million full-time equivalent (FTE) researchers versus about 1.7 million in the United States. On a per-capita basis the U.S. is ahead—about 4,500 researchers per million people versus China’s 1,700—but population scale tips the balance. China simply has more researchers in absolute terms. If you frame it in terms of rare cognitive talent, as in my post on The Extreme Shortage of High IQ Workers—the arithmetic is even more striking: 1-in-1,000 workers (≈IQ 145) ~170,000 in the U.S. labor force and ~770,000 in China. Scale matters.

In the 20th century the world’s most populous countries were poor but that was neither the case historically nor will it be true in the 21st century. The standard of living in China remains well below that in the United States and China may never catch U.S. GDP per capita, but quantity is a quality of its own. More people means more ideas.

To be clear, the rise of China and India as scientific superpowers is not per se a threat. Whiners complain about US pharmaceutical R&D “subsidizing” the world. Well, Chinese pharmaceutical innovation is now saving American lives. Terrific. Ideas don’t stop at borders, and their spread raises living standards everywhere. It would be wonderful if an American cured cancer. It would be 99% as wonderful if a Chinese scientist did. What matters is that when more scientists attack the problem, the odds of a cure rise so we should look favorably on a world with more scientists. That is progress.

The danger is not China’s rise but America’s mindset. Treat science as zero-sum and every Chinese patent looks like a loss. But ideas are nonrival: a Chinese breakthrough doesn’t make Americans poorer, it makes the world richer. A multi-polar scientific world means faster growth, greater wealth, and accelerating technology—even if America wins a smaller share of the Nobels.

Read it and weep

A global bond sell-off deepened on Wednesday, driving the yield on the 30-year US Treasury to 5 per cent for the first time since July, as investors’ fears over rising debt piles and stubbornly high inflation dominated trading.

Longer-dated bonds bore the brunt of the selling, with the yield on the 30-year Treasury up 0.03 percentage points at 5 per cent and Japan’s 30-year bond yield hitting a record high of 3.29 per cent.

In the UK, long-term borrowing costs climbed further after reaching their highest level since 1998 on Tuesday. The 30-year gilt yield rose 0.06 percentage points to 5.75 per cent.

Here is more from the FT.

Could China Have Gone Christian?

The Taiping Rebellion is arguably the most important event in modern history that even educated Westerners know very little about. It’s also known as the Taiping Civil War and it was one of the largest conflicts in human history (1850–1864), with death toll estimates ranging from 20 to 30 million, far exceeding deaths in the US civil war (~750,000) with which it overlapped. The civil war destabilized Qing China, weakening it against foreign powers and shaped the trajectory of 19th- and 20th-century Chinese politics. In China the Taiping Civil War is considered the defining event of the 19th-century.

The most surprising aspect of the civil war is that the rebels were Christian. The rebellion has its genesis in 1837 with the dramatic visions of Hong Xiuquan. In his visions, Hong and his elder brother traveled the world slaying demons, guided onwards by an old man who berated Confucius for failing to teach proper doctrines to the Chinese people. (I draw here on Steven Platt’s excellent Autumn in the Heavenly Kingdom). It is perhaps not coincidental that Hong began experiencing his visions after failing the infamously stressful Chinese civil service exams for the third time. It wasn’t until 1843, however, after he failed the exams for the fourth time, that he had an epiphany. A Christian tract that he had never read before suddenly unlocked the meaning of his visions–the elder brother was Jesus Christ, making Hong the second son of the old man, God.

With his visions unlocked, Hong threw himself into learning and then teaching the Gospels. He quickly converted his cousin and a neighbor and they baptized themselves and began taking down icons of Confucianism at their local school. Confucianism, of course, underpinned the exam system that Hong had grown to hate (Recall, that a similar pattern is visible in India today, where mass exams generate large numbers of educated but frustrated youth).

The wild visions of a lowly scholar wouldn’t seem to have the makings of a revolutionary movement but this was the beginning of the century of humiliation when China was forced to confront the idea that far from being the center of civilization it was in fact a backward and weak power on the world stage. Moreover, China was governed by foreigners, the Manchus, who despite ruling for 200 years had never really integrated with the Chinese population. Hence, Hong’s calls to kill the demons merged with a nationalist fervor to massacre the Manchus. Hong proclaimed himself the Heavenly King and his movement quickly grew to more than a million zealous warriors who captured significant territory including establishing the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom with its capital at Nanjing.

The regime banned foot‑binding, prostitution and slavery, promoted the equality of men and women, distributed bibles, and instituted a 7-day week with strict observance of the sabbath. To be sure, this was a Sinicized, millenarian Christianity, more Old Testament than new but the Christianity was serious and real and the rebels appealed to British and Americans as their Christian brothers. One Taiping commander wrote to a British counterpart:

You and I are both sons of the Heavenly Father, God, and are both younger brothers of the Heavenly Elder Brother, Jesus. Our feelings towards each other are like those of brothers, and our friendship is as intimate as that of two brothers of the same parentage. (quoted in Platt p.40)

Now, as it happened, the Heavenly Kingdom fell to the Qing, but it was a close thing and could easily have gone the other way. Western powers—above all Britain, but also the United States—hedged their bets and at times fought both sides, yet for short-sighted reasons ultimately tilted toward the Qing, an intervention Ito Hirobumi later called “the most significant mistake the British ever made in China.” Internal purges fractured the movement, alliances went unmade, and crucial opportunities slipped away. Yet the moment was pregnant with possibility. Hong Rengan, Hong Xiuquan’s cousin and prime minister from 1859, pushed sweeping modernization: railroads, steamships, postal services, banks, and even democratic reforms. These initiatives would likely have brought what one might call Christianity with Chinese Characteristics into closer alignment with Western Christianity.

Indeed, it is entirely plausible that with only a few turns of history, China might now be the world’s most populous Christian nation. And if that seems hard to believe, consider what did happen. Sixty three years after the fall of Nanjing in 1864, China again erupted into civil war under Mao Zedong. This time the rebels triumphed, and instead of a Christian Heavenly Kingdom the world got a Communist People’s Republic. The parallels are striking: both Hong and Mao led vast zealous movements that promised equality, smashed tradition, and enthroned a single man as the embodiment of truth. Both drew on foreign creeds—Hong from Protestant Christianity, Mao from Marxism-Leninism. Both movement had excesses but of the counter-factual and the factual I have little doubt which promised more ruin. The Heavenly Kingdom pointed toward a biblical moral order aligned with the West, the People’s Republic toward a creed that delivered famine, purges, and economic stagnation. Such are the contingencies of history—an ill-timed purge in Nanjing, a foreign gunboat at Shanghai, a missed alliance with the Nian. Small events cascaded into vast consequences. For the want of a nail, the Heavenly Kingdom was lost, and with it perhaps an entirely different modern world.

Policy uncertainty matters right now

More than half of Fourth District business contacts said that “uncertainty and the potential impact on demand” was the most important factor influencing their capital expenditure plans for the rest of 2025. Contacts most often reported that their inventory levels were the same as they were one year ago, though more firms reported lower inventory levels than higher ones. More than half of firms anticipated that they would work through their current inventories in one to three months. Most survey respondents said that one-fourth or less of their current inventory had been subject to additional duties in 2025 because of changes to trade policy.

Here is more from the Cleveland Fed.

I podcast with Jacob Watson-Howland

He is a young and very smart British photographer. He sent me this:

Links to the episode:

Youtube: https://youtu.be/4nMg0Qg7KRI

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/episode/2wDyCaXhGN5ruN1SNkcaBt?si=3c054eb0396f4787

Apple: https://podcasts.apple.com/gb/podcast/watson-howland/id1813625992?i=1000724051310

Jacob’s episode summary is at the first link.

What are the markets telling us?

That is the topic of my latest piece for The Free Press, as after all stock valuations are high. Excerpt:

First, the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, passed earlier this year, slashed corporate taxes. Before Trump’s first term, the corporate tax rate was 35 percent; in his first term Trump cut it to 21 percent, and this year he and the Republican Congress extended aspects of that first-term tax bill. Factors such as 100 percent bonus depreciation and expanded interest deductions give many companies the ability to lower their tax bill further, though not in a way that can be expressed readily by any single number.

With these lower tax burdens, companies should be worth much more. At the same time, the American taxpayer now owes more than $37 trillion in debt. So someone has to pay higher taxes over time, to satisfy those obligations. That someone probably is you, so you might want to take that into account in your overall assessment. But you should feel good about the companies, and somewhat less good about yourself and your children, given the tax hikes in the offing, sooner or later. You are paying for some of those higher stock market values.

Plus the ten or so percent decline in the value of the dollar can be seen as a loss of confidence in the United States, for a bunch of the obvious reasons. But will the country fall apart? Probably not:

That said, some of the worries are exaggerated. I’ve seen lots of posts on X lately saying that Trump is destroying the independence of the Federal Reserve system, and that this change will bring much higher rates of price inflation. Maybe. But that is not what the markets are saying. There are different measures of expected inflation, and most stand between 2 and 3 percent, with some of the more important market measures clustered near 2.5 percent. You might think that is higher than it should be, but it is hardly a sign of pending hyperinflation. It’s also not different from how things were toward the close of Joe Biden’s term.

And this:

Finally, are you worried about fascism coming to America? The collapse of democracy? Did you read about the Trump critics Jason Stanley, Timothy Snyder, and Marci Shore moving from America to Canada?

Well, head on over to the prediction markets—for instance, Kalshi. Currently the Democrats are favored at 53 percent to win the next presidential election. In other words, it costs 53 cents to buy a security that pays off a dollar if the Democrats win. In turn, that means the market thinks the Democrats have a very slight advantage in 2028. Does that sound like the collapse of democracy to you?

I return here to the same logic: If you think the market is being naive and foolish, why aren’t you placing your bets in the opposite direction? At the very least you could be wealthier under the forthcoming fascism you predict, and you might even be able to donate your winnings to antifascist causes.

Comments that fail to understand the distinction between optimal ex ante prediction and ex post outcomes should be shamed!