Category: Data Source

Karl Storchmann reports from the front: French wines vs. Jersey wines

At the Princeton tasting, led by George Taber, 9 wine judges from France, Belgium and the U.S. tasted French against New Jersey [TC: that’s the New Jersey] wines. The French wines selected were from the same producers as in 1976 including names such as Chateau Mouton-Rothschild and Haut Brion, priced up to $650/bottle. New Jersey wines for the competition were submitted to an informal panel of judges, who then selected the wines for the competition. These judges were not eligible to taste wines at the final competition The results were similarly surprising. Although, the winner in each category was a French wine (Clos de Mouches for the whites and Mouton-Rothschild for the reds) NJ wines are at eye level. Three of the top four whites were from New Jersey. The best NJ red was ranked place 3. An amazing result given that the prices for NJ average at only 5% of the top French wines.

A statistical evaluation of the tasting, conducted by Princeton Professor Richard Quandt, further shows that the rank order of the wines was mostly insignificant. That is, if the wine judges repeated the tasting, the results would most likely be different. From a statistically viewpoint, most wines were undistinguishable. Only the best white and the lowest ranked red were significantly different from the others wines.

There was a third similarity to the Paris tasting. In Paris, after the identity of wines was revelared, Odette Kahn, editor of La revue Du Vin De France, demanded her score card back. Apparently, she was not happy with having rated American wines number one and two.

At the Princeton blind tasting, while both French judges preferred NJ red wines over the counterparts from Bordeaux. After disclosing the wines’ identity the French judges were surprised but did not complain. In contrast, several tasters from the U.S. did not want their wine ratings to be published.

All results and the statistical analysis can be found here:

http://wine-economics.org/WineTastings/Judgment_of_Princeton_no_comments.html

Orley Ashenfelter also refers me to www.liquidasset.com, click on “tastings” and then “the latest” for data.

We are not as wealthy as we thought we were

The Census Bureau has released new data on wealth:

The recent financial crisis left the median American family in 2010 with no more wealth than in the early 1990s, erasing almost two decades of accumulated prosperity, the Federal Reserve said on Monday.

The median family, richer than half of the nation’s families and poorer than the other half, had a net worth of $77,300 in 2010, down from $126,400 in 2007, the Fed said. The crash of housing prices explained three-quarters of the loss.

This vast loss of wealth was compounded by a loss of income, as the earnings of the median family fell by 7.7 percent over the same period.

The story is here. Matt adds comment and posts a good chart.

Why has Foreign Aid Been Untied?

The more cynical among us have sometimes thought that rather than recipient welfare the purpose of “foreign” aid is to provide a cover for domestic aid. Foreign aid pork, i.e. using foreign aid to subsidize special interests in the donor country has certainly been common. Historically, most foreign aid has been tied; that is, the recipient was required to spend the money on the donor country’s exports. Relative to cash, tying raises prices and reduces choice and recipient welfare–the deadweight loss of Christmas problem.

US food aid is a classic example. US food aid tends to peak after a glut. It’s cheaper for us to give food away when we have lots and not coincidentally giving food away after a glut helps to keep prices higher, benefiting US farmers. It’s precisely when food is plenty, however, that prices are low and aid is less needed. When food is scarce, prices are high and aid is more needed but then we would rather sell our food than give it away. In addition, we typically require food aid to be transported on US ships which raises costs. Finally, the food we give away is not always best suited to the recipient’s preferences or needs.

For a public choice theorist the fact that foreign aid benefits domestic special interests is not at all surprising. What is surprising is that tied aid is way down. Great Britain banned most tied aid in 2002 and indeed tied aid is down across all of the major OECD donor countries. Food aid and technical assistance are still tied but these aid categories are down and untied grants and loans are up. In 1984-1986, for example, about 60% of aid was tied and today only 10-25% of aid is tied (depending on source).

Why has aid become untied? Could this be a case of improved public policy due to lobbying from the aid industry? It is interesting to note that although tied aid is down in the US, the US continues to tie a lot of aid, considerably more than the Europeans. One explanation may be that the decentralized US political system gives more weight to local domestic interests so tied aid continues to sell here despite opposition from most aid groups.

Special interests are also not the only explanation for tied aid. Tied aid can reduce corruption in the recipient country. If donors have become less worried about corruption, perhaps because governance has improved in the developing world, this could offer a public interest explain for an increase in untied aid.

Overall, I find it puzzling that foreign aid has become untied as the major beneficiaries appear to be poor foreigners with little political power.

CSI: Independent

Fingerprints, DNA testing, blood samples and other crime evidence are much more open to interpretation and judgment than is suggested by television or by the police. As a result, I agree with Roger Koppl and E. James Cowan that there needs to be a Wall of Separation between forensic science and law enforcement:

Fingerprints, DNA testing, blood samples and other crime evidence are much more open to interpretation and judgment than is suggested by television or by the police. As a result, I agree with Roger Koppl and E. James Cowan that there needs to be a Wall of Separation between forensic science and law enforcement:

If you work for the police, you tend to see things from that point of view. Same goes for the prosecution. Usually, it is not a conscious thing. You want to be fair and unbiased, and you think you are. But when the boss hopes you’ll find evidence to support her point of view, your mistakes may lean in that direction.

…Crime labs should produce unbiased scientific evidence. In order to be as unbiased as possible, they should report to independent boards. The boards should represent a diverse group of stakeholders, including a local prosecutor, a prominent defense attorney, a representative from the public defender’s office, a traditional scientist working, perhaps, at a university, and a forensic scientist from another jurisdiction.

Falling public investment in the United Kingdom

Paul Krugman draws our attention to the following chart (via Portes):

Maybe that really is worrisome. Still, if I look at the longer run chart — which is on p.14 from this pdf — sorry it will not reproduce — I start thinking that the matter is more complex. After all, in the early 1970s the figure for public investment was well over thirty billion pounds, and it is mostly falling sharply except for the late 1980s and very early 1990s. In the year 2000 it ends up at around five billion pounds, about one sixth the initial level. Yet the 1970s were pretty awful times for Great Britain, with pretty awful economic policies.

Why is public sector investment falling so much over the longer term? Mostly it is the decline in the number of public corporations, a healthy development if you ask me. Check out Figure 2 on p.15 of the same paper, noting the difference between net and gross investment. You also will see that changes in local government have been more important than changes at the national level.

If you read this paper, which runs to 2000 or so, you will see that public investment in health services has been plummeting for a long time, well before Cameron or “austerity,” defense spending seems to be included in these figures, and a lot of transport is not included in these numbers at all. I am happy to take corrections if things are done differently now.

Now what is the recent decline in public investment due to? I do not know, and in part I am asking for your help. I really am willing to believe that the United Kingdom is not investing enough in its future, including in science and education, but we haven’t yet gotten to the bottom of this matter. How much of that decline in the first graph is simply due to defense spending cuts and a shifting composition of expenditure for the national health care service, as higher service bills crowd out investment? How much is driven by changes in the housing market? (Here is a good historical source on changes in public housing policy over the longer term.) How do the recent declines in public investment compare to the longer term trend? How much is driven by a change in the gross rather than the net?

By the way, to cite a separate but related debate, to the extent immediate health care expenditures are pushing out health care investment, should that really count as “austerity”? I don’t think so, however mistaken such a policy may be, and thus I don’t see why “net public investment” is the proper metric for the short-run stance of fiscal policy (for that matter the “gross” figure may be more appropriate for short-run macro).

Inquiring minds wish to know. I hope that inquiring British minds wish to know too, or better yet already do know. I will gladly reproduce the best of what we learn from the comments.

Addendum: Here is a published data series. I am not sure I understand the notation, but my initial reading seems to suggest that current data are not out of line with the longer-term trend, including under Labour.

Shout it from the rooftops, Matt!

Matt Yglesias shouts it from the rooftops on occupational licensing:

Licensing requirements…are by far the best statistical predictor of business-friendliness, for those subjected to them. And unlike taxes or environmental rules, these have spread like kudzu, with little scrutiny and often scant policy rationale.

A recent comprehensive survey of state licensing practices by the Institute for Justice reveals little consistency or coherent purpose behind most licensing. Nevada, Louisiana, Florida, and the District of Columbia, for example, all require aspiring interior designers to undergo 2,190 hours of training and apprenticeship and pass an exam before practicing. In the other 47 states, meanwhile, there’s no legal training requirement. My friends and co-workers living in D.C.’s Virginia and Maryland suburbs appear to get on fine with unlicensed interior decorators, and all across America, amateurs have decorated their own homes without imperiling public safety.

Almost all states—though not Alabama or the anarchic United Kingdom—require barbers to be licensed, but the specific requirements seem to vary arbitrarily. New York barbers need 884 days of education and apprenticeship. Across the river in New Jersey, it’s 280. But getting one’s hair cut in New Jersey (to say nothing of England) is hardly a life-threatening gamble.

…a wide range of these rules could be done away with entirely at basically no risk. Regulation is needed when it would make sense for a firm to deliberately engage in malfeasance. Dumping harmful toxins into the air is highly profitable unless it’s prohibited. Financiers can draw huge bonuses by taking on too much risk, only to wreck the economy later. In other occupations, though, shoddy work brings its own punishments. An interior decorator who can’t get recommendations from satisfied customers probably won’t remain an interior decorator for long.

In these cases, licensing rules raise the prices the rest of us pay, make it difficult for successful entrepreneurs to expand their businesses, and are often a major barrier to employment for the most vulnerable populations.

We have covered these issues before on MR but sometimes you just have to KEEP SHOUTING.

The reshoring of U.S. (and Mexican) manufacturing

Some 65 per cent of the senior executives questioned by Accenture said they had moved their manufacturing operations in the past 24 months, with two-fifths saying the facilities had been relocated to the US. China was the second destination for relocated factories, with 28 per cent, followed by Mexico with 21 per cent.

Here is more.

Update on the Millennium Villages controversy

G., a loyal MR reader, writes to me:

I imagine you may find this interesting…

The blog post: http://blogs.worldbank.org/impactevaluations/the-millennium-villages-project-impacts-on-child-mortality

The retraction on the MVP website: http://www.millenniumvillages.org/field-notes/millennium-villages-project-corrects-lancet-paper

The retraction in the Lancet:

http://press.thelancet.com/MVP.pdf

…from the Lancet editors…http://download.thelancet.com/flatcontentassets/pdfs/S0140673612607879.pdf

Related:

http://www.economist.com/node/21555571

http://www.economist.com/blogs/newsbook/2012/05/jeffrey-sachs-and-millennium-villages?fsrc=gn_ep

http://blog.givewell.org/2012/05/18/millennium-villages-project/

Genoeconomics

An interesting piece from the Boston Globe on “genoeconomics”:

Though the name wasn’t coined until 2007, genoeconomics flickered briefly into existence once before. In 1976, the late University of Pennsylvania economist Paul Taubman published the results of a study in which he followed the financial lives of identical twins, and found there were curious similarities in how much money they made as adults. Taubman concluded that between 18 percent and 41 percent of variation in income across individuals was heritable.

It was a startling conclusion, and one that Taubman’s fellow economists didn’t quite know what to do with. One joked that Taubman’s findings meant the government might as well shut down welfare, since clearly some people would remain poor no matter what.

….After Taubman, the idea that genes had an important role to play in decision-making was largely abandoned in the world of economics. But with the completion of the Human Genome Project in 2000, the first full sequence of a human being’s genetic code, people started wondering if perhaps it would be possible to push past broad heritability estimates, of the sort that Taubman generated, and figure out what part of a person’s genome influenced what aspect of his behavior.

…Over time, social scientists started coming to terms with the fact that even the most heritable of traits, such as height, were influenced not by one or two powerful genes, but by a combination of hundreds or even thousands—and that environmental factors, like a person’s upbringing, play a complex role in determining how those genes are expressed. “Every single direction has proved to be less promising than people originally expected,” said Laibson.

… hope lies in a new approach to data-gathering that is only just getting underway, wherein researchers look for patterns among thousands, and even millions of people—numbers that are only just becoming possible thanks to massive collaborations linking gene studies being conducted all over the world.

The researchers in question, Daniel Benjamin, David Laibson, David Cesarini and others, seem worried about the possibility of tracing attributes and behavior to genetics. Most of the big news is out already, however, and more easily observed in phenotype than genotype.

For more on the new approach see The genetic architecture of economic and political preferences.

Facts about JP Morgan

The banking unit of JPMorgan Chase alone made $12.4 billion last year. The holding company has over $2.26 trillion in assets and is the largest U.S. bank and 8th largest in the world. The holding company made $29.9 billion in operating income and just over $20 billion in net income for 2011.

So, this initial loss of $800M [TC: with more to come] represents approximately 4% of its total net profit for all of 2011, less than 2.7% of its operating income. Certainly it’s not a good thing. But the reported losses, in and of themselves, are not likely to have a dramatic impact on JPMorgan’s long-term financial stability.

Here is more, hat tip to Angus as well. A $2 billion loss is about one percent of their equity and about 0.1% of their assets.

Addendum: Sober Look adds a good point.

Gay Marriage Politics

From the NYTimes:

President Obama’s endorsement of gay marriage on Wednesday was by any measure a watershed.

…Mr. Obama faces considerable risk in jumping into this debate, reluctantly or not, in the heat of what is expected to be a close election.

As of today, however, Intrade shrugged it off; that could mean the issue won’t play much of a role or that the political forces are equally balanced but that volatility could be higher in the future. My guess is the former, a lot of talk but when it comes to swing votes no action. We have come a long way.

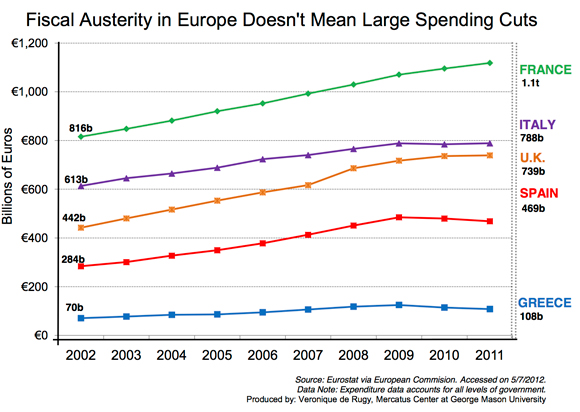

How savage has European austerity (spending cuts) been?

To be sure, there are particular small countries which have made serious spending cuts, in the Baltics most of all. But sometimes one hears it said that an anti-austerity strategy must be EU-wide as a whole, or that austerity is “a failed strategy for the eurozone,” or something similar. So perhaps it is worth looking at some numbers for the larger picture. Here is a graph which puts the matter in some perspective:

Veronique de Rugy, who compiled this data, writes:

First, I wish we would stop being surprised by what’s happening in Europe right now. Second, I wish anti-austerity critics would start acknowledging that taxes have gone up too–in most cases more than the spending has been cut. Third, I wish that we would stop assuming that gigantic “savage” cuts are the source of the EU’s problems. Some spending cuts have been implemented in a few countries. Also, if this data were adjusted for inflation (which I would prefer but the data isn’t available) it would possibly show a slight decrease and certainly a flatter line for all countries. However, the overwhelming take away from the European experience is that a majority of governments haven’t really implemented spending cuts, large or small, and some have even continued to grow.

There is further discussion at the link. Via Pat Lynch, here you will find OECD data, no country is spending below its 2004 level.

Addendum: My response from the comments section:

The real question addressed by this post is how bad spending cuts have been in nominal terms, keeping in mind in the short run it is supposedly nominal which matters (that said, gdp and population [and inflation] are not skyrocketing in these countries for the most part). It is fine to argue “due to automatic stabilizers, spending should have increased more than it did.” That is not how people phrase it, rather they are complaining rather vociferously about “spending cuts,” many of which are either imaginary or extremely small.

From the shrillness of responses, and by the frequency of frame switching, one can see how this post and this data have hit a raw nerve.

The African Growth Miracle?

I had not previously read this 2009 paper by Alwyn Young (pdf):

Measures of real consumption based upon the ownership of durable goods, the quality of housing, the health and mortality of children, the education of youth and the allocation of female time in the household indicate that sub-Saharan living standards have, for the past two decades, been growing in excess of 3 percent per annum, i.e. more than three times the rate indicated in international data sets.

National income statistics, which in this context are untrustworthy, indicate a growth rate of only about one percent. Contra Young, here is a much less positive perspective, excerpt:

Yet this is nothing like the required economic advancement built around an actual or dominant “middle-class” milieu as commonly and quite wrongly suggested.

Africa’s burgeoning demography will challenge this future. Subsistence economies remain its anchors, and the alleged “demographic dividend”, that some blithely portray as a “driver”, will mostly transform into one of rising unemployment and growing informalisation.

Those who observe the lack of significant gains in African agricultural productivity often prefer the negative interpretation. Too many of the observed progress seems to come from mining wealth. In a recent short essay, Michael Lipton sums it up:

1. Stop kidding ourselves. (a) Faster GDP growth in Africa since 2000 is mainly a mining boom, with dubious benefits. Staples yields (and labour productivity) have not reversed the dismal trends that Peter Timmer diagnosed two decades ago: big, credible rises are seen in only a few African countries (e.g. Rwanda, Ghana). The populous ones (Ethiopia, Nigeria, maybe Kenya, above all DR Congo) tell a sad tale.

That we don’t know who is right is perhaps the most interesting fact of all.

The idea of the “food desert” is fading

Poor neighborhoods, Dr. Lee found, had nearly twice as many fast food restaurants and convenience stores as wealthier ones, and they had more than three times as many corner stores per square mile. But they also had nearly twice as many supermarkets and large-scale grocers per square mile. Her study, financed by the institute, was published in the March issue of Social Science and Medicine.

From another paper:

Dr. Sturm found no relationship between what type of food students said they ate, what they weighed, and the type of food within a mile and a half of their homes.

Here is much more.

What if we live longer?

The IMF asks what would happen if life expectancy by 2050 turns out to be three years longer than current projected in government and private retirement plans: “[I]f individuals live three years longer than expected–in line with underestimations in the past–the already large costs of aging could increase by another 50 percent, representing an additional cost of 50 percent of 2010 GDP in advanced economies and 25 percent of 2010 GDP in emerging economies. … [F]or private pension plans in the United States, such an increase in longevity could add 9 percent to their pension liabilities. Because the stock of pension liabilities is large, corporate pension sponsors would need to make many multiples of typical annual pension contributions to match these extra liabilities.”

This is one reason (of several) why “doing fine against the baseline” does not much impress me as a fiscal standard. I hope to cover that broader topic soon.