Category: Data Source

New results on the missing women question

This paper (pdf) came out about two years ago, by Siwan Anderson and Debraj Ray, in the highly esteemed Review of Economic Studies, yet I haven’t seen it discussed in the blogosphere, so here goes:

Relative to developed countries and some parts of the developing world, most notably sub-Saharan Africa, there are far fewer women than men in India and China. It has been argued that as many as a 100 million women could be missing. The possibility of gender bias at birth and the mistreatment of young girls are widely regarded as key explanations. We provide a decomposition of these missing women by age and cause of death. While we do not dispute the existence of severe gender bias at young ages, our computations yield some striking new findings: (1) the vast majority of missing women in India and a significant proportion of those in China are of adult age; (2) as a proportion of the total female population, the number of missing women is largest in sub-Saharan Africa, and the absolute numbers are comparable to those for India and China; (3) almost all the missing women stem from disease-by-disease comparisons and not from the changing composition of disease, as described by the epidemiological transition. Finally, using historical data, we argue that a comparable proportion of women was missing at the start of the 20th century in the United States, just as they are in India, China, and sub-Saharan Africa today.

That is a very different interpretation from what one usually hears.

Excess Reserves and Intraday Credit

In my 2008 post, Interpreting the Monetary Base Under the New Monetary Regime, I argued that the massive increase in bank reserves was neither a necessary harbinger of inflation (as people on the right feared) nor a sure sign of a liquidity trap (as people on the left claimed) but rather represented, at least in part, a sensible aspect of the new regime of paying interest on reserves. I wrote:

When no interest was paid on reserves banks tried to hold as few as possible. But during the day the banks needed reserves – of which there were only $40 billion or so – to fund trillions of dollars worth of intraday payments. As a result, there was typically a daily shortage of reserves which the Fed made up for by extending hundreds of billions of dollars worth of daylight credit. Thus, in essence, the banks used to inhale credit during the day – puffing up like a bullfrog – only to exhale at night. (But note that our stats on the monetary base only measured the bullfrog at night.)

Today, the banks are no longer in bullfrog mode. The Fed is paying interest on reserves and they are paying at a rate which is high enough so that the banks have plenty of reserves on hand during the day and they keep those reserves at night. Thus, all that has really happened – as far as the monetary base statistic is concerned – is that we have replaced daylight credit with excess reserves held around the clock.

A post today at Liberty Street Economics, the blog of the New York Federal Reserve illustrates and explains how the excess reserves have reduced transaction costs in the payment system and risk to the Federal Reserve.

The last chart shows the level of intraday credit extended by the Federal Reserve to Fedwire participants, measured as the daily maximum amount extended by the Federal Reserve. There has been a dramatic decline in the amount of credit extended since the expansion of reserve balances in October 2008. The reduced level of daylight credit has the benefit of reducing the risk exposure of Federal Reserve Banks, as well as the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation’s (FDIC) fund. Indeed, the expected losses to that fund would be greater if some of the assets of a failed bank had been pledged to a Federal Reserve Bank to collateralize a daylight overdraft, as the collateral would not be available to pay other creditors of the bank. With a greater amount of reserves in the system, banks largely “prepay” for their liquidity needs by maintaining large reserve balances with which to fund their outgoing payments.

China fact of the day

The richest 70 members of China’s legislature added more to their wealth last year than the combined net worth of all 535 members of the U.S. Congress, the president and his Cabinet, and the nine Supreme Court justices.The net worth of the 70 richest delegates in China’s National People’s Congress, which opens its annual session on March 5, rose to 565.8 billion yuan ($89.8 billion) in 2011, a gain of $11.5 billion from 2010, according to figures from the Hurun Report, which tracks the country’s wealthy. That compares to the $7.5 billion net worth of all 660 top officials in the three branches of the U.S. government.

The wealth gap between legislatures holds with statistically comparable samples. The richest 2 percent of the NPC — 60 people — had an average wealth of $1.44 billion per person. The richest 2 percent of Congress — 11 members — had an average wealth of $323 million.

The wealthiest member of the U.S. Congress is Representative Darrell Issa, the California Republican who had a maximum wealth of $700.9 million in 2010, according to the center. If he were in China’s NPC, he would be ranked 40th. Per capita income in China is about one-sixth the U.S. level when adjusted for differences in purchasing power.

That is via Shanghaiist, via @AlbertoNardelli via @AnnieLowrey.

From the comments, on the UK

This is from a loyal reader named “a”:

How high are marginal rates of deductions in the UK?:

Consider an employee paid £50,000 gross who gets a £1,000 pay rise.

Let’s assume they are yet to pay off their student loan and contribute 7.5% to a (underfunded*) pension scheme and get 8% employer contributions to their pension.

Our employee’s employer will also pay the government an extra £218 pension contributions and national insurance (payroll) contributions, 8% and 13.8% of gross earnings respectively.

So the total increase in cost to the employer is £1,218.

Of their pay rise our employee pays £75 pension contributions, £90 student loan repayments, and £370 in income tax, giving total employee deductions £555.

This gives a marginal deduction rate of 63.46% (£445/£1,218).

If our employee buys goods which are liable for VAT they will lose a further 20%, resulting in a 70.77% marginal rate of deductions.

Oh and our employee must pay a local government lump sum tax of around £1,500 from their net wages.

So our employee faces a marginal rate of deductions 63.46% on non-VAT items, 70.77% on VAT items, and an average rate of deduction of 52% of pre-deduction earnings.

A similar analysis on a worker paid the minimum wage (around £12,500 a year), or £1000 above the minimum wage results in a marginal rate of deduction of 32% and an average rate of deduction of 52%. This ignores the withdrawal of means tested benefits.

Might this be the supply side explanation Scott Sumner has been looking for?

* UK private pension schemes currently have a £265bn deficit.

Immigration fact of the day

From Dan Griswold, via Bryan Caplan:

The typical foreign-born adult resident of the United States today is more likely to participate in the work force than the typical native-born American. According to the U.S. Department of Labor (2011), the labor-force participation rate of the foreign-born in 2010 was 67.9 percent, compared to the native-born rate of 64.1 percent. The gap was especially high among men. The labor-force participation rate of foreign-born men in 2010 was 80.1 percent, a full 10 percentage points higher than the rate among native-born men.

Labor-force participation rates were highest of all among unauthorized male immigrants in the United States. According to estimates by Jeffrey Passell (2006) of the Pew Hispanic Center, 94 percent of illegal immigrant men were in the labor force in the mid-2000s.

Unemployment Insurance and Disability Applications

More than 8.5 million workers are now collecting disability insurance, in other words almost 6% of the labor force is officially disabled. Perhaps not surprisingly, disability applications shot up just as unemployment benefits started to exhaust.

Applications are often denied so disability beneficiaries do not follow applications immediately. Denied applicants, however, often contest and apply again so eventually 50-60% of those who apply will typically enter the disability rolls and start to collect. Far fewer will ever exit the rolls, at least not by way of a job.

Since 1995 the number of disabled workers has doubled and expenditures have increased even faster than disabled workers, tripling since 1995. The increase in workers receiving disability insurance has come at the same time as the US working age population has become healthier. A large fraction of the increase in disability has come from increases in hard-to-verify back pain and mental problems (see Autor and Duggan and more recently Autor).

After the 2001 recession, disability applications also shot up and they never fell back to their old levels. We may be reaching a new, permanently higher, plateau.

Disabled workers do not count as unemployed, they have been bought out of the labor force.

The conservative critique of unemployment insurance used to be that it discouraged people from looking for work. The modern conservative response may be that it encourages people to not become disabled.

Scott Winship summary on mobility and inequality

Read it here, excerpt:

…evidence on earnings mobility in the sense of where parents and children rank suggests that our uniqueness lies in how ineffective we are at lifting up men who were poor as children. In other words, we have no more downward mobility from the middle than other nations, no less upward mobility from the middle, and no less downward mobility from the top. Nor do we have less upward mobility from the bottom among women. Only in terms of low upward mobility from the bottom among men does the U.S. stand out.

Labor market fact of the day

Although Latinos make up only a seventh of the population, they have “racked up half the employment gains posted since the economy began adding jobs in early 2010”, the Los Angeles Times reported this morning. In 2011, the trend accelerated. Of the 2.3 million jobs added in 2011 according to the Household Survey of the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1.4 million, or 60 percent, were won by Latinos.

This remarkable statistic is a keyhole into America’s two-speed recovery. One true story of the recession is that employment gains have been biased toward the highly educated. More than half of the jobs added in 2011 went to Americans with a college education. Another true story of the recession is that most of the other jobs have been low-paid and went to the less-educated. Educational attainment among Hispanics remains very low. Just 10% of foreign-born and 13.5% of native Latinos have finished college, placing the group’s completion rate at about a third of the national average.

That is from Derek Thompson, there is much more here. Here is one piece of the explanation:

Finally, it’s not just where they’re working. It’s where they’re not working. As a group, Hispanics have low employment in local, state, and federal governments, which lost about 300,000 jobs in 2011, the vast majority of net job losses last year. The upshot is that Hispanics are growing as a population faster than other groups; more likely to work in states with growing jobs, such as Texas; more likely to seek out low-wage positions in health care and hospitality that are fast-growing industries; and less likely to be sitting in the way of the austerity bulldozer that took down total government in 2011.

Apple fact of the day

Courtesy of Ajay Makan and Dan McCrum at the FT, Barclays Capital estimates that based on reporting thus far earnings growth for S&P 500 companies was 7 percent in Q4. But if you strip out Apple, that plummets to 2.9 percent.

One company, in other words, is responsible for most of the earnings growth among the large cap firms in the index.

(Pulls out Albert Hirschman for re-read…)

Innovation Nation v. Warfare-Welfare State (more)

The New York Times has a lengthy piece on the expansion of the welfare state:

The government safety net was created to keep Americans from abject poverty, but the poorest households no longer receive a majority of government benefits.

…Dozens of benefits programs provided an average of $6,583 for each man, woman and child in the county in 2009, a 69 percent increase from 2000 after adjusting for inflation.

…The recent recession increased dependence on government, and stronger economic growth would reduce demand for programs like unemployment benefits. But the long-term trend is clear. Over the next 25 years, as the population ages and medical costs climb, the budget office projects that benefits programs will grow faster than any other part of government, driving the federal debt to dangerous heights.

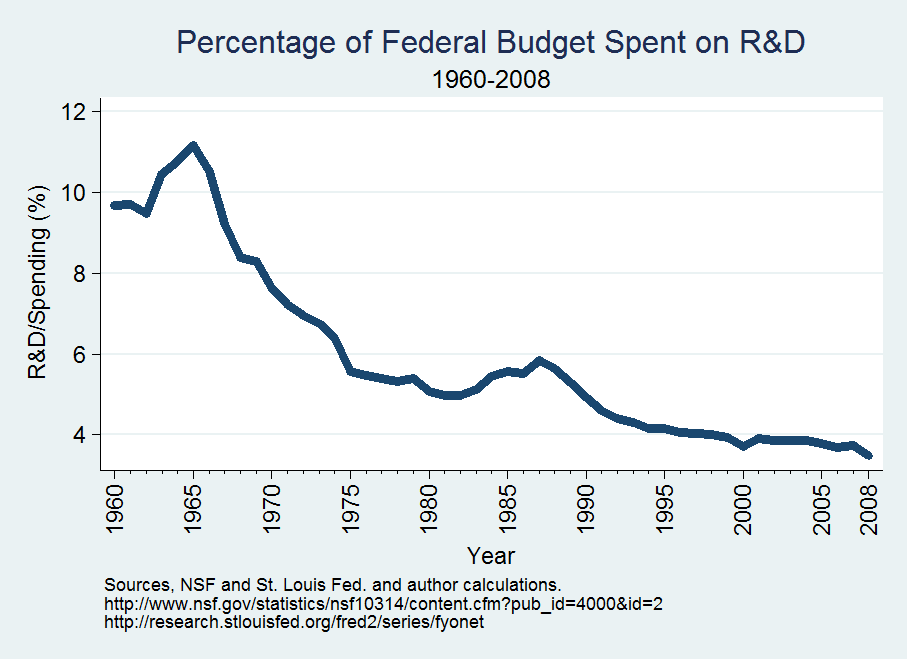

In Launching the Innovation Renaissance (and here) I argue that the warfare-welfare state is crowding out other areas of spending, even when such spending could be highly valuable.

What else predicts mobility?

Jim Manzi makes some good points:

But what about all the other potential reasons, beyond what their Gini Coefficient was in 1985, for varying levels of social mobility between countries as diverse as Japan, France, and New Zealand?

The most obvious example is just the size of the countries. It’s at least plausible that much bigger countries contain more variety. In fact, if you do something as simple as recreate the Great Gatsby Curve, but use the population of each country as the X-axis, you get a very strong a statistical relationship (log-linear R2 = .64). Big countries have higher IGE. Call it the Moby Dick Curve.

Alternatively, we might see that some countries tend to specialize more than others. As a practical example, part of the reason that a country like Finland can have so much equality and social mobility versus America might be that many more of the relatively poorer farmers who trade food for Finnish mobile phones live and reproduce in other countries. If so, then we might see that if we replace the X-axis with exports as a % of GDP, there could be another statistically significant relationship with IGE. Check (R2 = .48).

A fragment to ponder

The RGDP growth rate has been 1.6% in the 4 quarters since late 2010, which is below everyone’s estimate of trend growth (except perhaps Tyler Cowen…

There is much more at the link, from Scott Sumner. Of course Michael Mandel, Peter Thiel, Garry Kasparov, and some others would quality as well.

The new jobs report

All good news, 243k up but lots more information in the numbers, try @JustinWolfers or @BetseyStevenson for details and interpretation. The “big loser” here?: Old Keynesianism. You really can get a recovery when the real shocks are moderately positive. You will note, as we have been told many many times by many many sources, fiscal and monetary policy have not been extremely pro-active in recent times; in fact the stimulus has been trickling to a close. The big winners, apart from the American public?: real business cycle theory. It is part of any cyclical explanation, whether one likes it or not.

Another big loser is those liquidity trap theories which tell us that positive real shocks are bad for the economy because the AD curve has a perverse slope, etc., and that negative shocks might help spur recovery. That theory is looking very weak, again. I consider it the weakest economic theory that has any currency in the serious economics blogosphere.

The real unemployment rate?

Similar variations of this adjusted unemployment rate make headlines now and again. Our colleague Ed Luce, for instance, noted in December that “if the same number of people were seeking work today as in 2007, the jobless rate would be 11 per cent”.

But what is striking about the broken line above isn’t where it now ends — at 10.3 per cent — but rather the lack of any meaningful, sustained improvement for more than two years.

This alternative measure has remained above 10 per cent since September 2009, and aside from a bit of skittishness (some of which is down to uncaptured seasonality) has mostly just moved sideways.

That is from Cardiff Garcia, here is more.

Human Capital

Nick Schulz has an interesting introduction to recent work on immigration and human capital that includes this figure:

The human capital stock is probably over-estimated since it imputes the value of non-market time at market wages but even counting non-market time at zero (not correct either) would give a human capital stock of $212 trillion, about 5 times the physical capital stock. Thinking about human capital reminds us that debates about immigration and education are debates about investment.