Category: Economics

How New Zealand invented inflation targeting

…the very next day, [Roger] Douglas appeared on TV declaring his intention to reduce inflation to ‘around 0 or 0 to 1 percent’ over the next couple of years, and then went on to make several similar comments in the following days.

Douglas would soften his stance on specific timelines but ask the Reserve Bank and Treasury to develop public inflation goals for the next few years that would support his earlier statements. The Bank added 1 percentage point to Douglas’s upper range to account for the measurement bias in inflation data at that time, arriving at a target range of 0–2 percent. Michael Reddell, head of the Reserve Bank’s monetary policy unit, said it was settled on ‘more by osmosis than by ministerial sign-off’.

This development led officials to entertain the idea of making inflation targets part of the Bank’s monetary policy framework. David J. Archer, a former Assistant Governor, said inflation targets were eventually chosen ‘as the least bad of the alternatives available’.

…A new Reserve Bank Act was passed in December 1989 and came into effect in February 1990. Governor Don Brash was tasked with reaching the 0–2 percent target by the end of 1992. To the great surprise of many, it was achieved a year ahead of schedule in December 1991.

What happened when Spain brought back the wealth tax?

From the Journal of Public Economics Twitter feed:

What happened when Spain brought back the Wealth Tax in 2011? Using variation in exposure, this paper finds: – No drop in savings, but drop in taxable wealth—mainly via legal avoidance – Asset shifting caused most revenue loss – Estimated revenue loss was 2.75x initial 2011 rev.

Here is the full paper by Mariona Mas-Montserrat, José María Durán-Cabré, and Alejandro Esteller-Moré. Via Jerusalem Demsas.

Walton University?

Axios: Two grandsons of Walmart founder Sam Walton plan to launch a private university focused on science and tech, located on the company’s old HQ campus near downtown Bentonville, Arkansas.

…The future university plans to offer innovative, flexible pathways to jobs in automation, logistics, biotech and computing — fields crucial to Northwest Arkansas’ future.

Many colleges and universities were created in the 1960s and 1970s but the majority of elite R1s emerged in the late 19th century and early 20th century, including notable private universities created from the entrepreneurial fortunes of Carnegie, Rockefeller, Stanford, Cornell, Hopkins and Rice among others.

We are perhaps now seeing a return to that creative period with Walton, Thomas Monaghan, Patrick Collison (Arc Institute) and most notably Joe Lonsdale at the University of Austin. Tech provides both the funds and the impetus to build something new and different. As Tyler and I argued, online education and AI will change education dramatically, perhaps returning us to a now-affordable Oxford style-tutorial system with the AIs as tutors.

The University of Austin, by the way, has excellent taste in economics textbooks.

Equity sentences to ponder

Relative to prior observational methods, the estimates suggest a substantial role for amenity substitution in explaining the gender pay gap—accounting for roughly two-thirds of the observed gap—and little role for amenities in explaining inequalities by race or parent background.

That is from a new paper by Alex Bell, via Daniel.

Trump Administration Launches Probe Into Yale’s Use of Hacked EJMR Data

Christopher Brunet offers his version of the story. While I believe the original research methods were unethical, I very much prefer not to have the federal government involved in this matter.

Hayek Goes Supersonic

When I post about lifting the ban on supersonic flight, smart commenters show up with charts: optimal fuel burn is at Mach 0.78–0.84, they say, or no one wants to pay thousands to save a few hours. Maybe. But my reply is always the same: Bottled water!

In 2024, Americans spent $47 billion a year on H₂O that they could get for nearly free. That still boggles my mind—but bottled water has passed the market test. I argue for lifting the SST ban, and similar policies, not because we know supersonics will work but because we don’t. Hayek reminds us that competition is a discovery procedure. Like science, markets generate knowledge by experiment—hypotheses are posted as prices, and the public accepts or rejects them through revealed preference. Fred Smith’s FedEx plan got a “C” in the classroom, but the market graded the experiment and returned an A in equity. Theory is great, but just as in science, there is no substitute for running the experiment.

Adam Tooze on European military spending

Now, you might think that the US figure is inflated by the notorious bloat within the American military-industrial complex. I would be the last person who would wish to minimize that. But the evidence suggests that the bias may be the other way around. American defense dollars likely go further than European euros.

Look for instance at the price of modern, third-generation battle tanks and the cost of self-propelled howitzers, which have been key to the fighting in Ukraine. German prices are far higher than their American counterparts.

And, as work by Juan Mejino-López and Guntram B. Wolff at the Bruegel policy think tank has shown, these higher costs have to do with smaller procurement runs and smaller procurement runs are, in turn, tied to the fragmentation of Europe’s militaries and their strong preference for national procurement.

Right-now there is often lamentation about the tendency of European militaries to import key weapons systems from the US. And there is, of course, plenty of geopolitical and political maneuvering involved, for instance, in Berlin’s initiative to build an air defense system heavily reliant American and Israeli missiles. As the data show, Germany does have a strong preference for imports from the US rather than its European neighbors.

But, on average, across the entire defense budget, the besetting sin of European militaries is not that they rely too heavily on foreign weapons, but that they import not enough. They are too self-sufficient. The problem is not that Germany buys too many weapons from the US, but that it buys too many in Germany.

National fragmentation creates the balkanized defense market, the inefficient proliferation of major weapons systems and in terms of global industrial competition, the small size of European defense contractors.

Here is the full Substack, very good throughout. Via Felipe.

The High Cost of Self-Sufficiency

Mike Riggs and his wife dreamed of returning to the land. It wasn’t as easy as it looks on Tik-Tok:

How many square feet of raised beds do you need to meet a toddler’s strawberry demand? I still don’t know. We dedicated 80 square feet to strawberries last season. The bugs ate half our harvest, and the other half equaled roughly what our kid could eat in a week.

Have you ever grown peas? Give them something to climb, and they’ll stretch to the heavens. Have you ever shelled peas? It is an almost criminal misuse of time. I set a timer on my phone last year. It took me 13 minutes to shell a single serving. Meanwhile, a two-pound bag of frozen peas from Walmart costs $2.42. And the peas come shelled.

…In addition to possums and deer, we’ve faced unrelenting assaults from across the eukaryotic kingdoms: the tomato hornworm caterpillar, the cabbage looper caterpillar, the squash vine borer, the aphid, the thrip, the earwig and the sowbug; cucurbit downy mildew, powdery mildew, collar rot, black rot, sooty mold, botrytis gray mold and stem canker; the nematode, the gray garden slug, the eastern gray squirrel, the eastern cottontail rabbit and the groundhog. All of these organisms reside in the North Carolina Piedmont and like to eat what we eat. Many of them work toward this existential goal while humans sleep, which is why the North Carolina State Agriculture Extension advises growers to inspect their plants at night. No, thank you.

…. In the early 1900s, one of my paternal great-grandfathers moved from urban Illinois to a homestead in Oklahoma. Our only picture of him was taken shortly before the Dust Bowl destroyed his farm. After his farm failed, he abandoned my great-grandmother and their children and migrated to California with thousands of other Okies. When my crops fail, I go to Whole Foods.

Some good lessons here in self-sufficiency, comparative advantage and the productivity of specialization and trade. Of course, it might have been easier for Mike had he read Modern Principles:

How long could you survive if you had to grow your own food? Probably not very long. Yet most of us can earn enough money in a single day spent doing something other than farming to buy more food than we could grow in a year. Why can we get so much more food through trade than through personal production? The reason is that specialization greatly increases productivity. Farmers, for example, have two immense advantages in producing food compared with economics professors or students: Because they specialize, they know more about farming than other people, and because they sell large quantities, they can afford to buy large-scale farming machines. What is true for farming is true for just about every field of production—specialization increases productivity. Without specialization and trade, we would each have to produce our own food as well as other goods, and the result would be mass starvation and the collapse of civilization.

Oh, and by the way, don’t forget Adam Smith, “What is prudence in the conduct of every private family can scarce be folly in that of a great kingdom.”

Deport Dishwashers or Solve All Murders?

I understand being concerned about illegal immigration. I definitely understand being concerned about murder, rape, and robbery. What I don’t understand is being more concerned about the former than the latter.

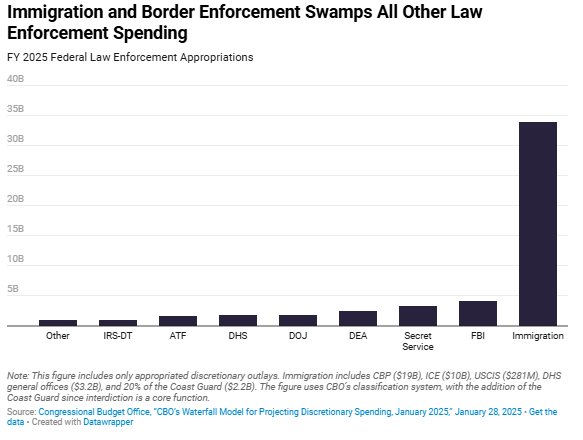

Yet that’s exactly how the federal government allocates resources. The federal government spends far more on immigration enforcement than on preventing violent crime, terrorism, tax fraud or indeed all of these combined.

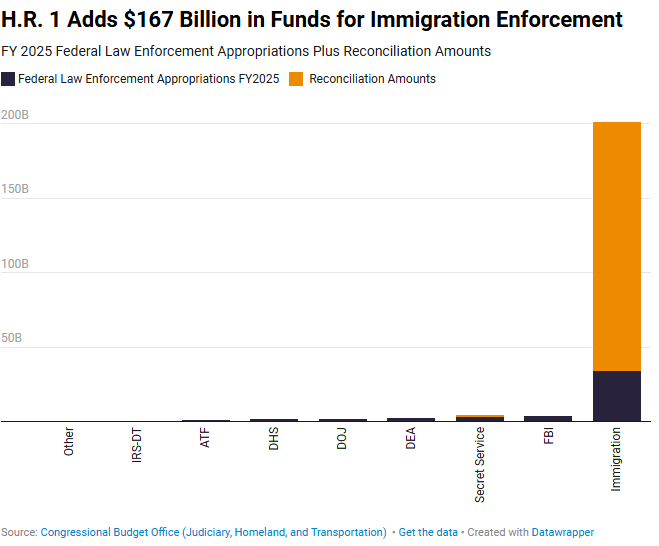

Moreover, if the BBB bill is passed the ratio will become even more extreme. (sere also here):

Don’t make the mistake of thinking that immigration enforcement is about going after murderers, rapists and robbers. It isn’t. Indeed, it’s the opposite. ICE’s “Operation At Large” for example has moved thousands of law enforcement personnel at Homeland Security, the FBI, DEA, and the U.S. Marshals away from investigating violent crime and towards immigration enforcement.

I’m not arguing against border enforcement or deporting illegal immigrants but rational people understand tradeoffs. Do we really want to spend billions to deport dishwashers from Oaxaca while rapes in Ohio committed by US citizens go under-investigated?

Almost half of the murders in the United States go unsolved (42.5% in 2023). So how about devoting some of the $167 billion extra in the BBB bill to say expand the COPS program and hire more police, deter more crime and to use Conor Friedersdorf’s slogan, solve all murders. Back of the envelope calculations suggest that $20 billion annually could fund roughly 150 k additional officers, a ~22 % increase, deterring some ~2 400 murders, ~90 k violent crimes, and ~260 k property crimes each year. Seems like a better deal.

Supersonics Takeoff!

In Lift the Ban on Supersonics I wrote:

Civilian supersonic aircraft have been banned in the United States for over 50 years! In case that wasn’t clear, we didn’t ban noisy aircraft we banned supersonic aircraft. Thus, even quiet supersonic aircraft are banned today. This was a serious mistake. Aside from the fact that the noise was exaggerated, technological development is endogenous.

If you ban supersonic aircraft, the money, experience and learning by doing needed to develop quieter supersonic aircraft won’t exist. A ban will make technological developments in the industry much slower and dependent upon exogeneous progress in other industries.

When we ban a new technology we have to think not just about the costs and benefits of a ban today but about the costs and benefits on the entire glide path of the technology

In short, we must build to build better. We stopped building and so it has taken more than 50 years to get better. Not learning, by not doing.

… I’d like to see the new administration move forthwith to lift the ban on supersonic aircraft. We have been moving too slow.

Thus, I am pleased to note that President Trump has issued an executive order to lift the ban on supersonics!

The United States stands at the threshold of a bold new chapter in aerospace innovation. For more than 50 years, outdated and overly restrictive regulations have grounded the promise of supersonic flight over land, stifling American ingenuity, weakening our global competitiveness, and ceding leadership to foreign adversaries. Advances in aerospace engineering, materials science, and noise reduction now make supersonic flight not just possible, but safe, sustainable, and commercially viable. This order begins a historic national effort to reestablish the United States as the undisputed leader in high-speed aviation. By updating obsolete standards and embracing the technologies of today and tomorrow, we will empower our engineers, entrepreneurs, and visionaries to deliver the next generation of air travel, which will be faster, quieter, safer, and more efficient than ever before.

…The Administrator of the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) shall take the necessary steps, including through rulemaking, to repeal the prohibition on overland supersonic flight in 14 CFR 91.817 within 180 days of the date of this order and establish an interim noise-based certification standard, making any modifications to 14 CFR 91.818 as necessary, as consistent with applicable law. The Administrator of the FAA shall also take immediate steps to repeal 14 CFR 91.819 and 91.821, which will remove additional regulatory barriers that hinder the advancement of supersonic aviation technology in the United States.

Congratulations to Eli Dourado who has been pushing this issue for more than a decade.

America’s Housing Supply Problem: The Closing of the Suburban Frontier?

Housing prices across much of America have hit historic highs, while less housing is being built. If the U.S. housing stock had expanded at the same rate from 2000-2020 as it did from 1980-2000, there would be 15 million more housing units. This paper analyzes the decline of America’s new housing supply, focusing on large sunbelt markets such as Atlanta, Dallas, Miami and Phoenix that were once building superstars. New housing growth rates have decreased and converged across these and many other metros, and prices have risen most where new supply has fallen the most. A model illustrates that structural estimation of long-term supply elasticity is difficult because variables that make places more attractive are likely to change neighborhood composition, which itself is likely to influence permitting. Our framework also suggests that as barriers to building become more important and heterogeneous across place, the positive connection between building and home prices and the negative connection between building and density will both attenuate. We document both of these trends throughout America’s housing markets. In the sunbelt, these changes manifest as substantially less building in lower density census tracts with higher home prices. America’s suburban frontier appears to be closing.

That is from a new NBER working paper by Edward L. Glaeser and Joseph Gyourko. The suburbs again are underrated. I am all for the various urban YIMBY ideas I hear, but keeping growth-viable suburbs up and running may be more important.

Not hard to geoguess this location…

Of course it is not in the state of Virginia…

Very Expensive Affordable Housing

In my post Affordable Housing is Almost Pointless, I highlighted how point systems for awarding tax credits prioritize DEI, environmental features, energy efficiency, and other secondary goals far more than low cost. A near-comic example comes from D.C., where so-called affordable housing units now cost between $800,000 and $1.3 million dollars each!

One such unit includes a “rooftop aquaponics farm to produce fresh fruits and vegetables for its tenants.” Another boasts “a fitness room to encourage physical activity, a library, a large café with an outdoor terrace, a large multi-purpose community room with a separate outdoor terrace, an indoor bike room, on-site laundry, lounges and balconies on every floor.”

The issue isn’t that the poor are getting better housing than many working-class D.C. residents. It’s that, with finite resources, the city could fund twice as many units at $400,000 than at $800,000. Secondary goals have overwhelmed affordability.

“There’s the desire of policymakers to ensure that affordable housing meets lots of other goals,” said Carolina Reid, an associate professor at the University of California at Berkeley who studies affordable housing costs. They tend to be worthy goals, she said, but they drive up costs, which results in fewer affordable housing units being built for those in need.

A report released in April by the nonprofit research organization Rand similarly said “unprecedented cost increases” in recent years have been due “in large part to the adoption of policies that prioritize factors other than the efficient production of affordable housing units.”

Of course, as costs rise, various groups along the way also get their slice of a bigger pie.

The kicker? Market-rate housing is cheaper to build than affordable housing!

Next door, the same developers built the Park Kennedy, for mostly market-rate tenants, at a per-unit cost of about $350,000, records show.

This is one reason I much prefer housing vouchers, aka Section 8, to government subsidized “affordable” housing.

Ideological Reversals Amongst Economists

Research in economics often carries direct political implications, with findings supporting either right-wing or left-wing perspectives. But what happens when a researcher known for publishing right-wing findings publishes a paper with left-wing findings (or vice versa)? We refer to these instances as ideological reversals. This study explores whether such researchers face penalties – such as losing their existing audience without attracting a new one – or if they are rewarded with a broader audience and increased citations. The answers to these questions are crucial for understanding whether academia promotes the advancement of knowledge or the reinforcement of echo chambers. In order to identify ideological reversals, we begin by categorizing papers included in meta-analyses of key literatures in economics as “right” or “left” based on their findings relative to other papers in their literature (e.g., the presence or absence of disemployment effects in the minimum wage literature). We then scrape the abstracts (and other metadata) of every economics paper ever published, and we deploy machine learning in order to categorize the ideological implications of these papers. We find that reversals are associated with gaining a broader audience and more citations. This result is robust to a variety of checks, including restricting analysis to the citation trajectory of papers already published before an author’s reversal. Most optimistically, authors who have left-to-right (right-to-left) reversals not only attract a new rightwing (left-wing) audience for their recent work, this new audience also engages with and cites the author’s previous left-wing (right-wing) papers, thereby helping to break down echo chambers.

That is from a new paper by Matt Knepper and Brian Wheaton, via Kris Gulati. If it is audience-expanding for researchers to write such papers, does that mean we should trust their results less?

Claims about debt and productivity growth

- To stabilize the debt-to-GDP ratio through productivity growth, we’d need to grow at an unrealistically fast rate. If productivity growth was 0.5 percentage point per year faster than CBO expects throughout the next three decades, then the ratio of debt-to-GDP would be stabilized. These estimates don’t include the effects of the 2025 tax bill now being debated in Congress; if that bill is enacted in the form it passed the House, we’d need even higher rates of productivity growth to stabilize the debt-to-GDP ratio.

- Pro-growth policies alone won’t get us there. The authors examine seven policy areas–immigration, housing, the safety net, electricity transmission, R&D, taxes on business investment, and permitting–and find no evidence that, even taken together, they can produce a sustained, large enough increase in productivity growth to offset their potential direct budgetary cost and significantly reduce the deficit.

- But while tax hikes and spending cuts will be needed, pro-growth policies could lessen the pain. Some policy changes in those areas would boost economic growth, and some of those changes would do so at a low enough direct budgetary cost that they would lower the trajectory of debt relative to GDP. For example, increasing the immigration of high-skilled workers or relaxing restrictions on housing construction would increase economic growth and lower the trajectory of debt.

- Pro-growth regulatory changes are especially promising. Some of these regulatory changes would be deregulatory–for example reforming permitting for infrastructure–and others would strengthen regulation–for example federal intervention to improve electricity transmission. Tax cuts, in contrast, directly widen budget deficits, and evidence suggests that they very rarely have a big enough impact on growth to offset those direct deficit increases.

That is from a new study by Douglas Elmendorf, Glenn Hubbard, and Zachary Liscow.