Category: Economics

Where do stock market returns come from?

Here is a new and sure to be controversial piece from the JPE:

Why does the stock market rise and fall? From 1989 to 2017, the real per capita value of corporate equity increased at a 7.2% annual rate. We estimate that 40% of this increase was attributable to a reallocation of rewards to shareholders in a decelerating economy, primarily at the expense of labor compensation. Economic growth accounted for just 25% of the increase, followed by a lower risk price (21%) and lower interest rates (14%). The period 1952–88 experienced only one-third as much growth in market equity, but economic growth accounted for more than 100% of it.

That is by Daniel L. Greenwald, Martin Leftau, and Sydney C. Ludvigson. Of course in more recent times it is tech stocks that have done very well, and they also tend to elevate pay standards.

The Madmen and the AIs

In Collaborating with AI Agents: Field Experiments on Teamwork, Productivity, and Performance Harang Ju and Sinan Aral (both at MIT) paired humans and AIs in a set of marketing tasks to generate some 11,138 ads for a large think tank. The basic story is that working with the AIs increased productivity substantially. Important, but not surprising. But here is where it gets wild:

[W]e manipulated the Big Five personality traits for each AI, independently setting them to high or low levels using P2 prompting (Jiang et al., 2023). This allows us to systematically investigate how AI personality traits influence collaborative work and whether there is heterogeneity in their effects based on the personality traits of the human collaborators, as measured through a pre-task survey.

In other words, they created AIs which were high and low on the “big 5” OCEAN metrics, Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness and Neuroticism and then they paired the different AIs with humans who were also rated on the big-5.

The results were quite amusing. For example, a neurotic AI tended to make a lot more copy edits unless paired with an agreeable human.

AI Alex: What do you think of this edit I made to the copy? Do you think it is any good?

Agreeable Alex: It’s great!

AI Alex: Really? Do you want me to try something else?

Agreeable Alex: Nah, let’s go with it!

AI Alex: Ok. 🙂

Similarly, if a highly conscientiousness AI and a highly conscientiousness human were paired together they exchanged a lot more messages.

It’s hard to generalize from one study to know exactly which AI-human teams will work best but we all know some teams just work better–every team needs a booster and a sceptic, for example– and the fact that we can manipulate AI personalities to match them with humans and even change the AI personalities over time suggests that AIs can improve productivity in ways going beyond the ability of the AI to complete a task.

Hat tip: John Horton.

Why LLMs are so good at economics

I can think of a few reasons:

At least for the time being, even very good LLMs cannot be counted on for originality. And at least for the time being, good economic reasoning does not require originality, quite the contrary.

Good chains of reasoning in economics are not too long and complicated. If they run on for very long, there is probably something wrong with the argument. The length of these effective reasoning chains is well within the abilities of the top LLMs today.

Plenty of good economics requires a synthesis of theoretical and empirical considerations. LLMs are especially good at synthesis.

In economic arguments and explanations, there are very often multiple factors. LLMs are very good at listing multiple factors, sometimes they are “too good” at it, “aargh! not another list, bitte…”

Economics journal articles are fairly high in quality and they are generally consistent with each other, being based on some common ideas such as demand curves, opportunity costs, gains from trade, and so on. Odds are that a good LLM has been trained “on the right stuff.”

A lot of core economics ideas are “hard to see from scratch,” but “easy to grasp once you see them.” This too plays to the strength of the models as strong digesters of content.

And so quality LLMs will be better at economics than many other fields of investigation.

Rethinking regulatory fragmentation

Regulatory fragmentation occurs when multiple federal agencies oversee a single issue. Using the full text of the Federal Register, the government’s official daily publication, we provide the first systematic evidence on the extent and costs of regulatory fragmentation. Fragmentation increases the firm’s costs while lowering its productivity, profitability, and growth. Moreover, it deters entry into an industry and increases the propensity of small firms to exit. These effects arise from redundancy and, more prominently, from inconsistencies between government agencies. Our results uncover a new source of regulatory burden, and we show that agency costs among regulators contribute to this burden.

That is from a new paper by Joseph Kalmenovitz, Michelle Lowry, and Ekaterina Volkova, forthcoming in Journal of Finance. Via the excellent Kevin Lewis.

Argentina’s DOGE

Cato has a good summary of Deregulation in Argentina:

- The end of Argentina’s extensive rent controls has resulted in a tripling of the supply of rental apartments in Buenos Aires and a 30 percent drop in price.

- The new open-skies policy and the permission for small airplane owners to provide transportation services within Argentina has led to an increase in the number of airline services and routes operating within (and to and from) the country.

- Permitting Starlink and other companies to provide satellite internet services has given connectivity to large swaths of Argentina that had no such connection previously. Anecdotal evidence from a town in the remote northwestern province of Jujuy implies a 90 percent drop in the price of connectivity.

- The government repealed the “Buy Argentina” law similar to “Buy American” laws, and it repealed laws that required stores to stock their shelves according to specific rules governing which products, by which companies and which nationalities, could be displayed in which order and in which proportions.

- Over-the-counter medicines can now be sold not just by pharmacies but by other businesses as well. This has resulted in online sales and price drops.

- The elimination of an import-licensing scheme has led to a 20 percent drop in the price of clothing items and a 35 percent drop in the price of home appliances.

- The government ended the requirement that public employees purchase flights on the more expensive state airline and that other airlines cannot park their airplanes overnight at one of the main airports in Buenos Aires.

- In January, Sturzenegger announced a “revolutionary deregulation” of the export and import of food. All food that has been certified by countries with high sanitary standards can now be imported without further approval from, or registration with, the Argentine state. Food exports must now comply only with the regulations of the destination country and are unencumbered by domestic regulations.

Needless to say, America’s DOGE could learn something from Argentina:

Milei’s task of turning Argentina once again into one of the freest and most prosperous countries in the world is herculean. But deregulation plays a key role in achieving that goal, and despite the reform agenda being far from complete, Milei has already exceeded most people’s expectations. His deregulations are cutting costs, increasing economic freedom, reducing opportunities for corruption, stimulating growth, and helping to overturn a failed and corrupt political system. Because of the scope, method, and extent of its deregulations, Argentina is setting an example for an overregulated world.

What should I ask Ken Rogoff?

Yes I will be doing a Conversation with him. He has a new book coming out, namely

Ken is tenured at Harvard, here is his Wikipedia page, here is Ken on scholar.google.com, here is o1 pro on Rogoff, and he also holds the title of chess grandmaster.

What Follows from Lab Leak?

Does it matter whether SARS-CoV-2 leaked from a lab in Wuhan or had natural zoonotic origins? I think on the margin it does matter.

First, and most importantly, the higher the probability that SARS-CoV-2 leaked from a lab the higher the probability we should expect another pandemic.* Research at Wuhan was not especially unusual or high-tech. Modifying viruses such as coronaviruses (e.g., inserting spike proteins, adapting receptor-binding domains) is common practice in virology research and gain-of-function experiments with viruses have been widely conducted. Thus, manufacturing a virus capable of killing ~20 million human beings or more is well within the capability of say ~500-1000 labs worldwide. The number of such labs is growing in number and such research is becoming less costly and easier to conduct. Thus, lab-leak means the risks are larger than we thought and increasing.

A higher probability of a pandemic raises the value of many ideas that I and others have discussed such as worldwide wastewater surveillance, developing vaccine libraries and keeping vaccine production lines warm so that we could be ready to go with a new vaccine within 100 days. I want to focus, however, on what new ideas are suggested by lab-leak. Among these are the following.

Given the risks, a “Biological IAEA” with similar authority as the International Atomic Energy Agency to conduct unannounced inspections at high-containment labs does not seem outlandish. (Indeed the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists are about the only people to have begun to study the issue of pandemic lab risk.) Under the Biological Weapons Convention such authority already exists but it has never been used for inspections–mostly because of opposition by the United States–and because the meaning of biological weapon is unclear, as pretty much everything can be considered dual use. Notice, however, that nuclear weapons have killed ~200,000 people while accidental lab leak has probably killed tens of millions of people. (And COVID is not the only example of deadly lab leak.) Thus, we should consider revising the Biological Weapons Convention to something like a Biological Dangers Convention.

BSL3 and especially BSL4 safety procedures are very rigorous, thus the issue is not primarily that we need more regulation of these labs but rather to make sure that high-risk research isn’t conducted under weaker conditions. Gain of function research of viruses with pandemic potential (e.g. those with potential aerosol transmissibility) should be considered high-risk and only conducted when it passes a review and is done under BSL3 or BSL4 conditions. Making this credible may not be that difficult because most scientists want to publish. Thus, journals should require documentation of biosafety practices as part of manuscript submission and no journal should publish research that was done under inappropriate conditions. A coordinated approach among major journals (e.g., Nature, Science, Cell, Lancet) and funders (e.g. NIH, Wellcome Trust) can make this credible.

I’m more regulation-averse than most, and tradeoffs exist, but COVID-19’s global economic cost—estimated in the tens of trillions—so vastly outweighs the comparatively minor cost of upgrading global BSL-2 labs and improving monitoring that there is clear room for making everyone safer without compromising research. Incredibly, five years after the crisis and there has be no change in biosafety regulation, none. That seems crazy.

Many people convinced of lab leak instinctively gravitate toward blame and reparations, which is understandable but not necessarily productive. Blame provokes defensiveness, leading individuals and institutions to obscure evidence and reject accountability. Anesthesiologists and physicians have leaned towards a less-punitive, systems-oriented approach. Instead of assigning blame, they focus in Morbidity and Mortality Conferences on openly analyzing mistakes, sharing knowledge, and redesigning procedures to prevent future harm. This method encourages candid reporting and learning. At its best a systems approach transforms mistakes into opportunities for widespread improvement.

If we can move research up from BSL2 to BSL3 and BSL4 labs we can also do relatively simple things to decrease the risks coming from those labs. For example, let’s not put BSL4 labs in major population centers or in the middle of a hurricane prone regions. We can also, for example, investigate which biosafety procedures are most effective and increase research into safer alternatives—such as surrogate or simulation systems—to reduce reliance on replication-competent pathogens.

The good news is that improving biosafety is highly tractable. The number of labs, researchers, and institutions involved is relatively small, making targeted reforms feasible. Both the United States and China were deeply involved in research at the Wuhan Institute of Virology, suggesting at least the possibility of cooperation—however remote it may seem right now.

Shared risk could be the basis for shared responsibility.

Bayesian addendum *: A higher probability of a lab-leak should also reduce the probability of zoonotic origin but the latter is an already known risk and COVID doesn’t add much to our prior while the former is new and so the net probability is positive. In other words, the discovery of a relatively new source of risk increases our estimate of total risk.

Wind turbines lower Danish real estate prices

We analyze the impact of wind turbines on house prices, distinguishing between effects of proximity and shadow flicker from rotor blades covering the sun. By utilizing data from 2.4 million house transactions and 6,878 wind turbines in Denmark, we can control for house fixed effects in our estimation. Our results suggest strong negative impacts on house prices, with reductions of up to 12 percent for modern giant turbines. Homes affected by shadow flicker experience an additional decrease in value of 8.1 percent. Our findings suggest a nuanced perspective on the local externalities of wind turbines regarding size and relative location.

Here is the full paper by Carsten Andersen and Timo Hener, via the excellent Kevin Lewis. I rather like how they look, and would gladly buy a home near some, if only for the scenery. Though I would rather have a nearby gas station instead?

China’s Medicines are Saving American Lives

The Economist reports that China is now the second largest producer of new pharmaceuticals, after the United States.

China has long been known for churning out generic drugs, supplying raw ingredients and managing clinical trials for the pharmaceutical world. But its drugmakers are now also at the cutting edge, producing innovative medicines that are cheaper than the ones they compete with.

… In September last year an experimental drug did what none had done before. In late-stage trials for non-small cell lung cancer, it nearly doubled the time patients lived without the disease getting worse—to 11.1 months, compared with 5.8 months for Keytruda. The results were stunning. So too was the nationality of the biotech company behind them. Akeso is Chinese.

This is exactly what I predicted in my TED talk and it’s great news! As I said then:

Ideas have this amazing property. Thomas Jefferson said “He who receives an idea from me receives instruction himself, without lessening mine. As he who lights his candle at mine receives light without darkening me.”

Now think about the following: if China and India were as rich as the United States is today, the market for cancer drugs would be eight times larger than it is now. Now we are not there yet, but it is happening. As other countries become richer the demand for these pharmaceuticals is going to increase tremendously. And that means an increase incentive to do research and development, which benefits everyone in the world. Larger markets increase the incentive to produce all kinds of ideas, whether it’s software, whether it’s a computer chip, whether it’s a new design.

Well if larger markets increase the incentive to produce new ideas, how do we maximize that incentive?

It’s by having one world market, by globalizing the world. Ideas are meant to be shared.

One idea, one world, one market.

Sadly, some of us are losing sight of the immense benefits of a global market. Another example of the great forgetting.

As Girard predicted, China’s growing similarity to the U.S. has fueled conflict and rivalry. But if managed properly, rivalry can be positive-sum. A rich China benefits us far more than a poor China—including by creating new cancer medicines that save American lives.

Hat tip: Cremieux.

My excellent Conversation with Ezra Klein

Ezra is getting plenty of coverage for his very good and very on the mark new book with Derek Thompson, Abundance. So far it is a huge hit after only a few days. I figured this conversation would be most interesting, and add the most value, if I tried to push him further from a libertarian point of view (a sign of respect of course). Here is the audio, video, and transcript. Here is part of the episode summary:

In this conversation, Ezra and Tyler discuss how the abundance agenda interacts with political polarization, whether it’s is an elite-driven movement, where Ezra favors NIMBYism, the geographic distribution of US cities, an abundance-driven approach to health care, what to do about fertility decline, how the U.S. federal government might prepare for AGI, whether mass layoffs in government are justified, Ezra’s recommended travel destinations, and more.

Lots of good back and forth, here is one excerpt:

COWEN: Here’s a question from a reader, and I’m paraphrasing. “I can see why you would favor Obamacare and an abundance agenda because Obamacare throws a lot more resources at the healthcare sector in some ways. It did have Medicare cuts, but nonetheless, it’s not choking the sector. But if you favor an abundance agenda, can you then possibly favor single-payer health insurance through the government, which does tend to choke resources and stifle innovation?”

KLEIN: I think it would depend on how you did the single-payer healthcare. Here, we should talk about — because it’s referenced glancingly in the book in a place where you and I differ — but the supervillain view that I hold and your view, which is that you should negotiate drug prices. I’ve always thought on that because I think in some ways, it’s a better toy example than single payer versus Obamacare.

I think you want to take the amount of innovation you’re getting very, very, very seriously. I’ve written pieces about this, that I think if you’re going to do Medicare drug pricing at any kind of significant level, you want to be pairing that with a pretty significant agenda to make drug discovery much easier, to make testing much easier.

And:

COWEN: What should the US federal government do to prepare for AGI? We should just lay off people, right?

KLEIN: [laughs] I would not say it that way. I wouldn’t say just lay off people. I think that’s some of what we’re doing.

COWEN: No, not just, but step one.

KLEIN: Do you think that’s step one? Do you buy this DOGE’s preparation-for-AGI argument that you hear?

COWEN: I think maybe a fifth of them think that. Maybe it’s step two or step three, but it’s a pretty early step, right?

KLEIN: I think that the question of AI or AGI in the federal government, in anywhere — and this is one reason I’ve not bought this argument about DOGE — is you have to ask, “Well what is this AI or AGI doing? What is its value function? What prompt have you given it? What have you asked it to execute across the government and how?”

Alignment, which we have primarily talked about in terms of whether or not the AI, the superintelligence makes us all into paperclips, is a constant question of just near-term systems as well. I think the question of how should we prepare for AGI or for AI in the federal government first has to do with deciding what we would like the AI or the AGI to do. That could be different things to different areas.

My sense — talking to a bunch of people in the companies has helped me conceptualize this better — is that the first thing I would do is begin to ask, what do I think the opportunities of AI are, scientifically and in terms of different kinds of discoveries…

And this:

COWEN: Let me give you another right-wing view, and tell me what you think. The notion that the most important feature of state capacity is whether a state has enough of its citizens willing to fight and die for it. In that case, the United States, Israel, but a pretty small number of nations have high state capacity, and most of Western Europe really does not because they don’t have militaries that mean anything. Is that just the number one feature of abundance in state capacity?

Recommended, obviously.

The New Geography of Labor Markets

We use matched employer-employee data to study where Americans live in relation to employer worksites. Mean distance from employee home to employer worksite rose from 15 miles in 2019 to 26 miles in 2023. Twelve percent of employees hired after March 2020 live at least fifty miles from their employers in 2023, triple the pre-pandemic share. Distance from employer rose more for persons in their 30s and 40s, in highly paid employees, and in Finance, Information, and Professional Services. Among persons who stay with the same employer from one year to the next, we find net migration to states with lower top tax rates and areas with cheaper housing. These migration patterns greatly intensify after the pandemic and are much stronger for high earners. Top tax rates fell 5.2 percentage points for high earners who stayed with the same employer but switched states in 2020. Finally, we show that employers treat distant employees as a more flexible margin of adjustment.

That is from a new NBER working paper by Mert Akan, et.al.

What do I think of the NIMBY contrarianism piece?

You know, the one from yesterday suggesting that tighter building restrictions have not led to higher real estate prices, at least not in the cross-sectional data? My sense is that it could be true, but we should not overestimate its import. In most circumstances, economists should focus on output, not prices per se. Let’s say we can build more homes, and prices for homes in that area do not fall. That can be a good thing! It is a sign that the homes are of high value, and people have the means to pay for them. It can be a sign that the higher residential density has not boosted crime rates, and so on. I find some of the more left-leaning YIMBY arguments are a bit too focused on distribution. I am happy if more YIMBY leads to a more egalitarian distribution of incomes, but I do not necessarily expect that. Often it leads to more agglomeration and higher wages, and high real estate prices too. The higher output and greater freedom of choice still are good outcomes.

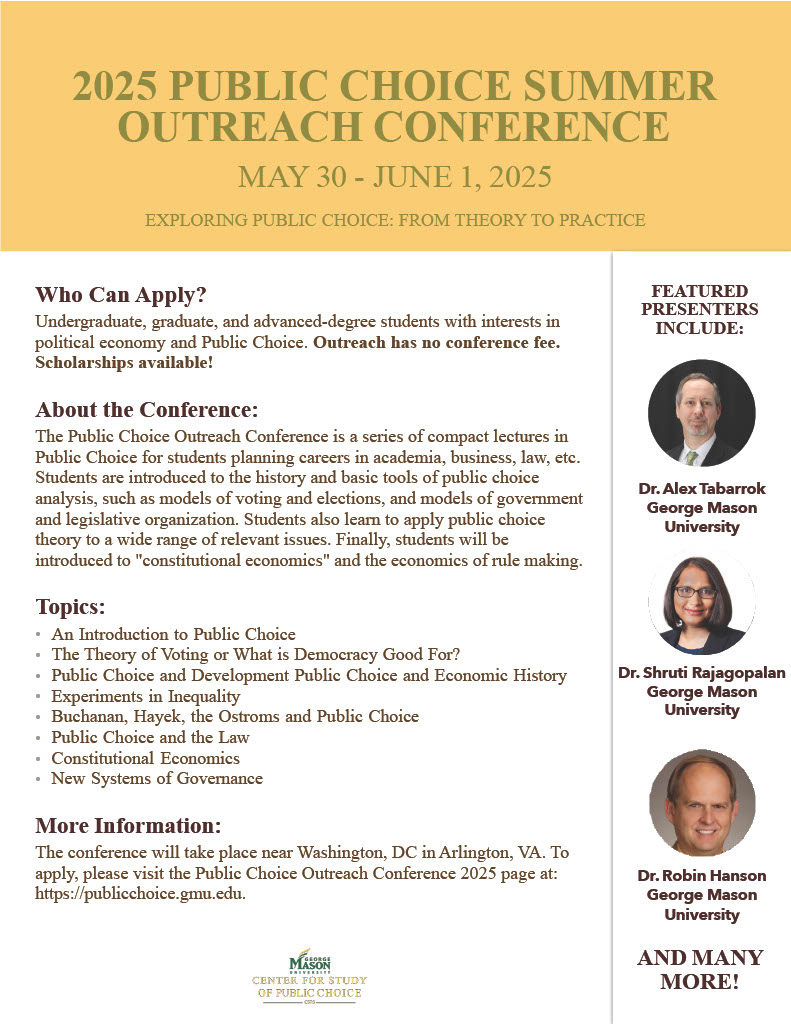

Public Choice Outreach Conference!

The annual Public Choice Outreach Conference is a crash course in public choice. The conference is designed for undergraduates and graduates in a wide variety of fields. It’s entirely free. Indeed scholarships are available! The conference will be held Friday May 30-Sunday June 1, 2025, near Washington, DC in Arlington, VA. Lots of great speakers. More details in the poster. Please encourage your students to apply.

NIMBY contrarianism

The standard view of housing markets holds that the flexibility of local housing supply–shaped by factors like geography and regulation–strongly affects the response of house prices, house quantities and population to rising housing demand. However, from 2000 to 2020, we find that higher income growth predicts the same growth in house prices, housing quantity, and population regardless of a city’s estimated housing supply elasticity. We find the same pattern when we expand the sample to 1980 to 2020, use different elasticity measures, and when we instrument for local housing demand. Using a general demand-and-supply framework, we show that our findings imply that constrained housing supply is relatively unimportant in explaining differences in rising house prices among U.S. cities. These results challenge the prevailing view of local housing and labor markets and suggest that easing housing supply constraints may not yield the anticipated improvements in housing affordability.

That is from a new NBER working paper by Schuyler Louie, John A. Mondragon, and Johannes Wieland.

The Shortage that Increased Ozempic Supply

It sometimes happens that a patient needs a non-commercially-available form of a drug, a different dosage or a specific ingredient added or removed depending on the patient’s needs. Compounding pharmacies are allowed to produce these drugs without FDA approval. Moreover, since the production is small-scale and bespoke the compounded drugs are basically immune from any patent infringement claims. The FDA, however, also has an oddly sensible rule that says when a drug is in shortage they will allow it be compounded, even when the compounded version is identical to the commercial version.

The shortage rule was meant to cover rare drugs but when demand for the GLP-1 drugs like Ozempic and Zepbound skyrocketed, the FDA declared a shortage and big compounders jumped into the market offering these drugs at greatly reduced prices. Moreover, the compounders advertised heavily and made it very easy to get a “prescription.” Thus, the GLP-1 compounders radically changed the usual story where the patient asks the compounder to produce a small amount of a bespoke drug. Instead the compounders were selling drugs to millions of patients.

Thus, as a result of the shortage rule, the shortage led to increased supply! The shortage has now ended, however, which means you can expect to see many fewer Hims and Hers ads.

Scott Alexander makes an interesting point in regard to this whole episode:

I think the past two years have been a fun experiment in semi-free-market medicine. I don’t mean the patent violations – it’s no surprise that you can sell drugs cheap if you violate the patent – I mean everything else. For the past three years, ~2 million people have taken complex peptides provided direct-to-consumer by a less-regulated supply chain, with barely a fig leaf of medical oversight, and it went great. There were no more side effects than any other medication. People who wanted to lose weight lost weight. And patients had a more convenient time than if they’d had to wait for the official supply chain to meet demand, get a real doctor, spend thousands of dollars on doctors’ visits, apply for insurance coverage, and go to a pharmacy every few weeks to pick up their next prescription. Now pharma companies have noticed and are working on patent-compliant versions of the same idea. Hopefully there will be more creative business models like this one in the future.

The GLP-1 drugs are complex peptides and the compounding pharmacies weren’t perfect. Nevertheless, I agree with Scott that, as with the off-label market, the experiment in relaxed FDA regulation was impressive and it does provide a window onto what a world with less FDA regulation would look like.

Hat tip: Jonathan Meer.