Category: Economics

Stablecoin podcast with Garett Jones

37 minutes, fresh material in here, see also Spotify under Bluechip Dialogues.

Gross(ery) Confusion

Zephyr Teachout’s NYTs op-ed on grocery store prices is poorly argued.

The food system in the United States is rigged in favor of big retailers and suppliers in several ways. Big retailers often flex their muscles to demand special deals; to make up the difference, suppliers then charge the smaller stores more.

Let’s be clear about what is actually going on. Costco offers its suppliers lower prices in return for bigger orders. There is nothing anti-competitive about volume discounting. Moreover, are firms dismayed or are they eager to sell to big, bad Costco? Google AI gives a good answer:

…firms are eager to sell to Costco because of the immense potential for sales and brand exposure, but they must be prepared to meet stringent requirements, negotiate competitive pricing, and be able to handle high volume and demanding logistics.

Would Americans be better off without Costco? Doubtful given that more than one-quarter of all Americans pay for a Costco membership (either individually or as a family).

Teachout’s idea that suppliers “make up the difference” by charging smaller stores more is also economically incoherent. Profit-maximizing firms already charge what the market will bear. If Costco’s volume justifies a discount, that doesn’t mean suppliers can or should charge higher prices to other buyers. Yes, there are models where costs change with volume but costs could go down with volume and, in any case, those models don’t rely on the folk theory of “making up the difference.”

That’s one of the subtler mistakes. Here’s a more glaring one:

Consider eggs. At the independent supermarket near my apartment, the price for a dozen white eggs last week was $5.99. At a major national retailer a few blocks away, it was $3.99. (For an identical box of cereal, the price difference was $3.) Any number of factors may contribute to a given price, but market power is a particularly consequential one.

Read that again: the firm allegedly abusing market power is the one charging less.

It gets stranger:

New York City has a strong price gouging law on the books, which forbids anyone — suppliers and retailers — from jacking up prices during a state of emergency unless the seller’s own costs have gone up accordingly. The city couldn’t have stopped the bird flu that devastated flocks, but maybe it can stop suppliers from cynically exploiting a crisis to justify exorbitant prices.

This makes two errors. First, she acknowledges it’s not gouging if costs rise—then cites egg prices rising due to the bird flu devastating flocks. That’s literally a textbook case of a supply shock. Maybe some firms exploited the crisis—but eggs rising in price after millions of chickens are killed is the best example you’ve got???

Second, within the span of a few paragraphs, the op-ed veers from claiming large retailers charge prices that are unfairly low to blaming them for charging prices that are too high. I’m surprised she didn’t go for the trifecta and accuse them of colluding to charge the same price.

AIs and Spontaneous Order

Tupy and Boettke in the WSJ on AI and the economy:

The belief that AI can achieve comparable results to free markets, let alone surpass them, reflects a misplaced confidence in computation and a misunderstanding of the price system. The problem for the would-be AI planners is that prices don’t exist like facts about the physical world for a computer to collect and process. They arise from competitive bidding over scarce resources and are inseparable from real market exchanges. Moreover, prices aren’t fixed inputs to be assumed in advance. They are continually being discovered and formed by entrepreneurs testing ideas about future consumer wants and resource constraints.

Economic models that treat prices as given overlook the entrepreneurial actions that create them in the first place. Ludwig von Mises made this point in 1920: Without real market exchange, central planners lack meaningful prices for capital goods. Consequently, they can’t calculate whether directing steel to railways rather than hospitals adds or destroys value.

I would another point. We are not going to have one AI to rule us all. Instead, there are going to be millions of agents who themselves will be participants in the market process. The buying and selling of the AI agents will contribute to the formation of prices but for all the Hayekian reasons that process will not be capable of being predicted.

As I said 7 years ago on Quora:

AIs will themselves be part of the economy. Firms and individuals use AIs to make decisions. Thus, any AI has to take into account the decisions of other AIs. But no AI is going to be so far advanced beyond other AIs that this will be possible. In other words, as AIs increase in power so does the complexity of the economy.

The problem of perfectly organizing an economy does not become easier with greater computing power precisely because greater computing power also makes the economy more complex.

This isn’t to say AI won’t help improve economic policy—it might, if we listen. But the future economy won’t look like a centrally planned machine. It will look like an economy of von Neumanns—autonomous agents buying, selling, and strategizing in complex interaction.

The America vs. Europe thing, again

From my latest column at The Free Press:

I worry much more about Europe in the longer run. Let’s consider how some of the most important comparisons between America and Europe are likely to change over the next 20 years.

Two of America’s biggest problems are obesity and opioid addiction, with opioid deaths running at about 54,000 a year. Yet both of those problems are getting better. GLP-1 drugs will help us beat back obesity, and finally opioid deaths have begun to decline. If this follows the path of previous drug epidemics, the decline will continue and perhaps accelerate.

More generally, we are entering a new age of fantastic biomedical innovations. These advances likely will help Americans more than Europeans, as Europeans are more likely to be in good shape to begin with, which is why Americans are more likely to need new and better treatments. That is, of course, a ding on America, but it will matter less as time passes.

One major advantage of America is likely to increase with time, and that is one of scale. Americans do things big, think big, and have created some of the world’s largest companies, most obviously in the tech sector, where size is often rewarded. You can see this in the stock market valuations of those tech companies, including Nvidia, which at its current $4 trillion or so valuation is worth more than the entire German stock market. Europe shows few if any signs of catching up in this area, or of having a major presence in the commercial spaces for artificial intelligence. If anything, EU regulations go out of their way to prevent Europe from excelling at tech.

Is tech likely to stop growing in economic and cultural influence? Have we reached peak application for current and future AI models? You can guess at the right answers to all of those questions. They imply that America’s economic lead over Europe will widen.

The brain drain from Europe (and other regions) to the United States seems to be accelerating in the areas of tech and AI, most of all for young people. If you want to do a big, successful start-up, you probably should move to America. End of story. America has major and growing companies in these areas, full of foreigners, and Europe does not.

Of course, a lot of that talent will not pay off right away. Not all of those smart and ambitious individuals will have big commercial hits at the age of 22. But more and more of them will by the age of 40. Europe has lost an increasing number of these people, and won’t be getting most of them back. The continent feels a bit of pain now, but the talent differential will de facto increase, if only due to the mere passage of time and the rising productivity of those people. It is not just about more people leaving; rather, those who already have moved to America will make a bigger and bigger difference over the next 10 to 15 years.

And:

The more general lack of European economic dynamism also is an issue that worsens with time. One recent economic study found that “Europeans switch jobs much less frequently, and restructuring is much rarer.” That is, of course, a problem, but in the short run the associated difficulties are not so large. If your economy remains static, after a year of progress elsewhere it is only missing out on so much beneficial change. After five years it is missing out on much more, and after 10 years much more yet. The more static and less dynamic nature of European economies naturally increases in size as a problem with the passage of time.

Population aging and low birth rates are another problem that will make it harder for Europe to catch up. The U.S. total fertility rate is about 1.63, whereas in the European Union it is about 1.38. Over time, this will make it harder for Europe to afford their current system of pensions. The major European populations also will be older than the American population, and probably as a result less innovative. This difference has only started to bite, and it is likely to grow in import.

I consider some other important issues, such as immigration, at the link.

Shorting Your Rivals: A Radical Antitrust Remedy

Conventional antitrust enforcement tries to prevent harmful mergers by blocking them but empirical evidence shows that rival stock prices often rise when a merger is blocked—suggesting that many blocked mergers would have increased competition. In other words, we may be stopping the wrong mergers.

In a clever proposal, Ayres, Hemphill, and Wickelgren (2024) argue that requiring merging firms to short the stock of a close competitor would powerfully realign incentives.

Suppose firms A and B want to merge. Regulators allow the merger on one condition: A-B must take a sizable short position in firm C, a direct competitor. If the merger is anti-competitive and leads to higher industry prices, C’s profits and stock price rise, and A-B takes a financial hit. But if the merger is pro-competitive and drives prices down, C’s stock falls and A-B profits.

A short creates two desirable effects:

- Selection Effect: Only those mergers that are expected to lower prices (and hurt rivals) are financially attractive to the merging parties.

- Incentive Effect: Post-merger, A-B has less incentive to raise prices because doing so boosts C’s stock price, triggering losses on the short.

The short isn’t perfect. Markets might be too shallow, or the rival’s stock could rise for unrelated reasons which imposes extra risk. The authors suggest fixes: instead of a short, require the firm to write Margrabe-style call option. These options have strike prices which float relative to another asset, for example a market or industry price. In this case, A-B would be penalized not if the market as a whole rose but only if the rival outperforms the market.

But the cleanest solution doesn’t require financial instruments at all. Just tie executive pay to relative performance—make the A-B CEO’s bonus depend on beating C’s performance. This is good for shareholders, aligns incentives even in private markets, and doesn’t require making big public bets.

Shorting your rivals sounds strange. But it’s a clever way to force firms to reveal whether their merger helps consumers—or just themselves. Or as I like to say, a bet is a tax on bullshit.

Hat tip: Kevin Lewis.

Addendum: See also this earlier paper, Incentive Contracts as Merger Remedies by Werden, Froeb and Tschantz.

Noah Smith on the economics of AI

What’s kind of amazing is that with the exception of Derek [Thompson], none of these writers even tried to question the standard interpretation of the data. They just all kind of assumed that although the national employment rate was near record highs, the narrowing of the gap between college graduates and non-graduates was conclusive evidence of an AI-driven apocalypse for white-collar workers.

But when people actually started taking a hard look at the data, they found that the story didn’t hold up. Martha Gimbel, executive director of The Budget Lab, pointed out what should have been obvious from Derek Thompson’s own graph — i.e., that most of the “new-graduate gap” appeared before the invention of generative AI. In fact, since ChatGPT came out in 2022, the new-graduate gap has been lower than at its peak in 2021!

In fact, the “new-graduate gap” is extremely cherry-picked. Unemployment gaps between bachelor’s degree holders and high school graduates for both ages 20-24 and ages 25+ look like they haven’t changed much in decades…

Overall, the preponderance of evidence seems to be very strongly against the notion that AI is killing jobs for new college graduates, or for tech workers, or for…well, anyone, really.

Here is the full post.

Markets in everything

At Cloudflare, we started from a simple principle: we wanted content creators to have control over who accesses their work. If a creator wants to block all AI crawlers from their content, they should be able to do so. If a creator wants to allow some or all AI crawlers full access to their content for free, they should be able to do that, too. Creators should be in the driver’s seat.

After hundreds of conversations with news organizations, publishers, and large-scale social media platforms, we heard a consistent desire for a third path: They’d like to allow AI crawlers to access their content, but they’d like to get compensated. Currently, that requires knowing the right individual and striking a one-off deal, which is an insurmountable challenge if you don’t have scale and leverage…

We believe your choice need not be binary — there should be a third, more nuanced option: You can charge for access. Instead of a blanket block or uncompensated open access, we want to empower content owners to monetize their content at Internet scale.

We’re excited to help dust off a mostly forgotten piece of the web: HTTP response code 402…

Pay per crawl, in private beta, is our first experiment in this area.

Here is the full post. I suppose over time, if this persists, it is the AIs bargaining back with you?

Labor supply is elastic!

Even in Denmark:

We investigate long-run earnings responses to taxes in the presence of dynamic returns to effort. First, we develop a theoretical model of earnings determination with dynamic returns to effort. In this model, earnings responses are delayed and mediated by job switches. Second, using administrative data from Denmark, we verify our model’s predictions about earnings and hours-worked patterns over the lifecycle. Third, we provide a quasi-experimental analysis of long-run earnings elasticities. Informed by our model, the empirical strategy exploits variation among job switchers. We find that the long-run elasticity is around 0.5, considerably larger than the short-run elasticity of roughly 0.2.

That is from a forthcoming American Economic Review piece by Henrik Kleven, Claus Kreiner, Kristian Larsen, and Jakob Søgaard. Via Alexander Berger.

Addendum: The rest of supply is elastic too.

Are tariffs a regressive tax?

I hear all the time that they are, but is that true?:

There are two sides to this. First, we need to figure out how consumption differs by income. Here it’s pretty clear that lower-income people consume more goods which are traded, and the goods which they consume have a lower elasticity of substitution (Fajgelbaum and Khandelwal, 2016). Put concretely, this is because the poor consume fewer luxuries which can’t be exchanged for other goods. In practice, the distributional effects in the United States are particularly large, because even within relatively narrow categories of goods lower quality goods face higher tax rates. (Acosta and Cox (2025) attribute this to a peculiarity of trade negotiations. The within category rates were shaped by negotiations in the 1930s, after which we no longer negotiated individual items but instead shifted all items within a category by a fixed percentage).

However, we need to take into account the effect of who gets more jobs. If it reallocates production to low-skill industries primarily employing the poor, then it may redistribute from top to bottom. Borusyak and Jaravel (2023) compare the two, and show that almost all of the redistribution is occurring within income deciles. Tariffs are costly to the consumer, and are indeed disproportionately costly to lower income consumers, but it does so by reallocating jobs to primarily lower income workers. Taking into account both effects, the distributional consequences of tariffs and trade are approximately nil.

Here is more from Nicholas Decker. These are the kinds of results that easily could be overturned by subsequent research (see the further remarks at the link), nonetheless at this time we probably should not be pushing regressive tariffs as established science or a firm conclusion. I’ll say it again: the best (and very good) argument against the tariffs is simply that they set the government on the trail of a previously dormant revenue source. That rarely ends well, though it is hard for non-libertarians to pick up this argument and run with it.

The Sputnik vs. Deep Seek Moment: The Answers

In The Sputnik vs. DeepSeek Moment I pointed out that the US response to Sputnik was fierce competition. Following Sputnik, we increased funding for education, especially math, science and foreign languages, organizations like ARPA were spun up, federal funding for R&D was increased, immigration rules were loosened, foreign talent was attracted and tariff barriers continued to fall. In contrast, the response to what I called the “DeepSeek” moment has been nearly the opposite. Why did Sputnik spark investment while DeepSeek sparks retrenchment? I examine four explanations from the comments and argue that the rise of zero-sum thinking best fits the data.

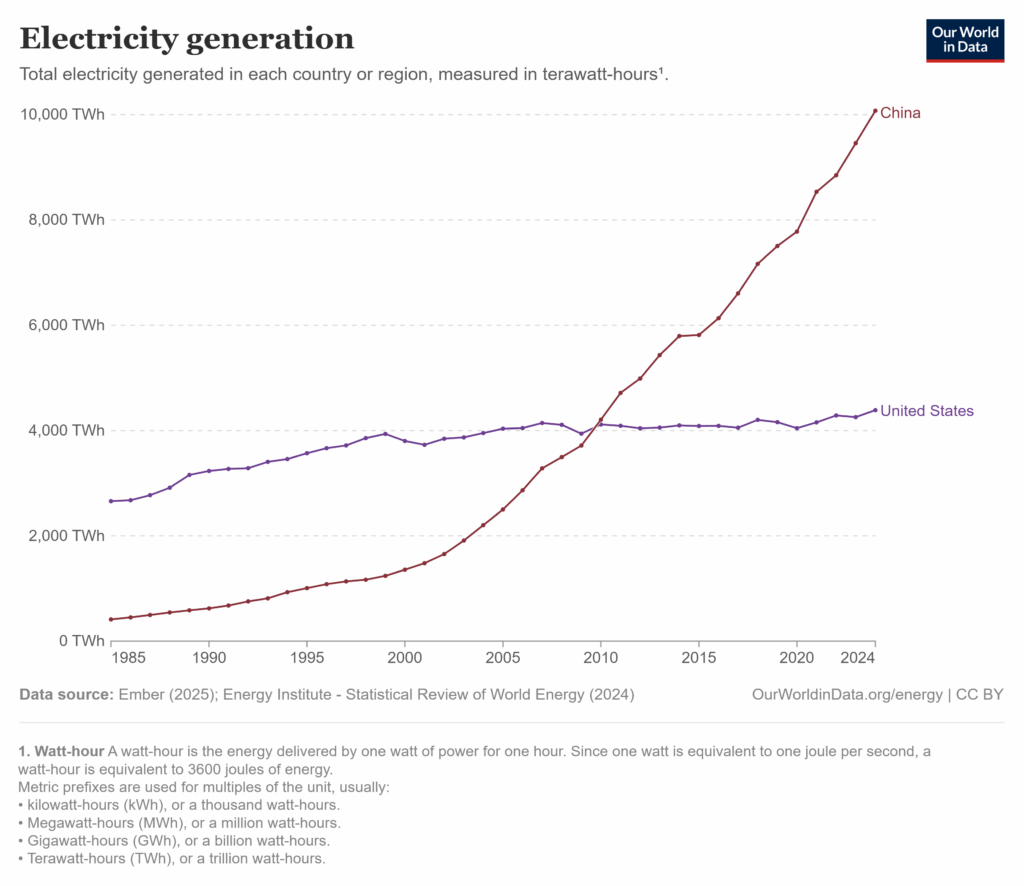

Several comments fixated on DeepSeek itself, dismissing it as neither impressive nor threatening. Perhaps but DeepSeek was merely a symbol for China’s broader rise: the world’s largest exporter, manufacturer, electricity producer, and military by headcount. These critiques missed the point.

Some commenters argued that Sputnik provoked a strong response because it was seen as an existential threat, while DeepSeek—and by extension China—is not. I certainly hope China’s rise isn’t existential, and I’m encouraged that China lacks the Soviet Union’s revolutionary zeal. As I’ve said, a richer China offers benefits to the United States.

But many influential voices do view China as a very serious, even existential, threat—and unlike the USSR, China is economically formidable.

More to the point, perceived existential stakes don’t answer my question. If the threat were greater, would we suddenly liberalize immigration, expand trade, and fund universities? Unlikely. A more plausible scenario is that if the threat were greater, we would restrict harder—more tariffs, less immigration, more internal conflict.

Several commenters, including my colleague Garett Jones, pointed to demographics—especially voter demographics. The median age has risen from 30 in 1950 to 39 in recent years; today’s older, wealthier, more diverse electorate may be more risk-averse and inward-looking. There’s something to this, but it’s not sufficient. Changes in the X variables haven’t been enough to explain the change in response given constant Betas so demography doesn’t push that far but does it even push in the right direction?

Age might correlate with risk-aversion, for example, but the Trump coalition isn’t risk-averse—it’s angry and disruptive, pushing through bold and often rash policy changes.

A related explanation is that the U.S. state has far less fiscal and political slack today than it did in 1957. As I argued in Launching, we’ve become a warfare–welfare state—possibly at the expense of being an innovation state. Fiscal constraints are real, but the deeper issue is changing preferences. It’s not that we want to return to the moon and can’t—it’s that we’ve stopped wanting to go.

In my view, the best explanation for the starkly different responses to the Sputnik and DeepSeek moments is the rise of zero-sum thinking—the belief that one group’s gain must come at another’s expense. Chinoy, Nunn, Sequiera and Stantcheva show that the zero sum mindset has grown markedly in the U.S. and maps directly onto key policy attitudes.

Zero sum thinking fuels support for trade protection: if other countries gain, we must be losing. It drives opposition to immigration: if immigrants benefit, natives must suffer. And it even helps explain hostility toward universities and the desire to cut science funding. For the zero-sum thinker, there’s no such thing as a public good or even a shared national interest—only “us” versus “them.” In this framework, funding top universities isn’t investing in cancer research; it’s enriching elites at everyone else’s expense. Any claim to broader benefit is seen as a smokescreen for redistributing status, power, and money to “them.”

Zero-sum thinking doesn’t just explain the response to China; it’s also amplified by the China threat. (hence in direct opposition to some of the above theories, the people who most push the idea that the China threat is existential are the ones who are most pushing the zero sum response). Davidai and Tepper summarize:

People often exhibit zero-sum beliefs when they feel threatened, such as when they think that their (or their group’s) resources are at risk…Similarly, working under assertive leaders (versus approachable and likeable leaders) causally increases domain-specific zero-sum beliefs about success….. General zero-sum beliefs are more prevalent among people who see social interactions as a competition and among people who possess personality traits associated with high threat susceptibility, such as low agreeableness and high psychopathy, narcissism and Machiavellianism.

Zero-sum thinking can also explain the anger we see in the United States:

At the intrapersonal level, greater endorsement of general zero-sum beliefs is associated with more negative (and less positive) affect, more greed and lower life satisfaction. In addition, people with general zero-sum beliefs tend to be overly cynical, see society as unjust, distrust their fellow citizens and societal institutions, espouse more populist attitudes, and disengage from potentially beneficial interactions.

…Together, these findings suggest a clear association between both types of zero-sum belief and well-being.

Focusing on zero-sum thinking gives us a different perspective on some of the demographic issues. In the United States, for example, the young are more zero-sum thinkers than the old and immigrants tend to be less zero-sum thinkers than natives. The likeliest reason: those who’ve experienced growth understand that everyone can get a larger slice from a growing pie while those who have experienced stagnation conclude that it’s us or them.

The looming danger is thus the zero-sum trap: the more people believe that wealth, status, and well-being are zero-sum, the more they back policies that make the world zero-sum. Restricting trade, blocking immigration, and slashing science funding don’t grow the pie. Zero-sum thinking leads to zero-sum policies, which produce zero-sum outcomes—making the zero sum worldview a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Markets in everything those new service sector jobs

Witchcraft and spellwork have become an online cottage industry. Faced with economic uncertainty and vapid dating apps, some people are putting their beliefs—and disposable income—into love spells, career charms and spirit cleansers.

Etsy, an online marketplace for crafts and vintage, has long been home to psychics and mystics, but the platform has enjoyed new callouts from TikTokers as a destination for witchcraft.

The concept of hiring an Etsy witch hit a fever pitch when influencer Jaz Smith told her TikTok followers that she had paid one to make sure the weather was perfect during her Memorial Day Weekend wedding. The blue skies and warm temperature have inspired TikTok audiences to find Etsy witches of their own. Smith didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Rohit Thawani, a creative director in Los Angeles, said Smith was his inspiration for paying an Etsy witch $8.48 to cast a spell on the New York Knicks ahead of Game 5 of the Eastern Conference finals in May.

Thawani found a witch offering discount codes. Thawani was half-kidding about the transaction but was amazed when the Knicks won. “Maybe there’s something more cosmic out there,” Thawani, 43, said.

Thawani bought a second spell ($21.18) from the Etsy witch for Game 6, but the Knicks lost. He doesn’t rule out the possibility that Indiana Pacers fans “used their devil magic,” he joked.

Magic practitioners sell on Instagram, Shopify and TikTok, but most customers say Etsy is their go-to.

The shop MariahSpells has over 4,000 sales on Etsy and 4.9 stars and sells a permanent protection spell for about $200. Another shop, Spells by Carlton, has over 44,000 sales and lists a “bring your ex lover back” spell for about $7.

Here is more from the WSJ, via the excellent Samir Varma.

Asymmetric economic power?

America’s trading partners have largely failed to retaliate against Donald Trump’s sweeping tariffs, allowing a president taunted for “always chickening out” to raise nearly $50bn in extra customs revenues at little cost.

Four months since Trump fired the opening salvo of his trade war, only China and Canada have dared to hit back at Washington imposing a minimum 10 per cent global tariff, 50 per cent levies on steel and aluminium, and 25 per cent on autos.

At the same time US revenues from customs duties hit a record high of $64bn in the second quarter — $47bn more than over the same period last year, according to data published by the US Treasury on Friday.

China’s retaliatory tariffs on American imports, the most sustained and significant of any country, have not had the same effect, with overall income from custom duties only 1.9 per cent higher in May 2025 than the year before.

Here is more from the FT. To be clear, I do not think this is good. Nonetheless it amazes me how many economists a) reject the “Leviathan” approach to analyzing public choice and U.S. government, b) think “normative nationalism” is fine, c) have expressed partial “trade skepticism” for some while, and d) think our government should raise a lot more revenue, including through consumption taxes…and yet they find this to be about the worst policy they ever have seen.

Some also will tell you that higher inflation is not such a terrible thing, though whether they extend this view to inflation from real shocks is disputable.

With some debatable number of national security exceptions, zero tariffs is the way to go. But you can only get there through broadly libertarian frameworks, not through conventional “mid-establishment” policy analyses.

Revisiting the Interest Rate Effects of Federal Debt

This paper revisits the relationship between federal debt and interest rates, which is a key input for assessments of fiscal sustainability. Estimating this relationship is challenging due to confounding effects from business cycle dynamics and changes in monetary policy. A common approach is to regress long-term forward interest rates on long-term projections of federal debt. We show that issues regarding nonstationarity have become far more pronounced over the last 20 years, significantly biasing the recent estimates based on this methodology. Estimating the model in first differences addresses these concerns. We find that a 1 percentage point increase in the debt-to-GDP ratio raises the 5-year-ahead, 5-year Treasury rate by about 3 basis points, which is statistically and economically significant and highly robust. Roughly three-quarters of the increase in interest rates reflects term premia rather than expected short-term real rates.

That is from a new NBER working paper by Michael Plante, Alexander W. Richter, and Sarah Zubairy.

Why is manufacturing productivity growth so low?

We examine the recent slow growth in manufacturing productivity. We show that nearly all measured TFP growth since 1987—and its post-2000s decline—comes from a few computer-related industries. We argue conventional measures understate manufacturing productivity growth by failing to fully capture quality improvements. We compare consumer to producer and import price indices. In industries with rapid technological change, consumer price indices indicate less inflation, suggesting mismeasurement in standard industry deflators. Using an input-output framework, we estimate that TFP growth is understated by 1.7 percentage points in durable manufacturing, 0.4 percentage points in nondurable manufacturing, with no mismeasurement in nonmanufacturing industries.

That is from a recent paper by Enghin Atalay, Ali Hortacsu, Nicole Kimmel, and Chad Syverson. Still, that seems low to me…

Via Adam Ozimek.

Tariff Shenanigans

In our textbook, Tyler and I give an amusing example of how entrepreneurs circumvented U.S. tariffs and quotas on sugar. Sugar could be cheaply imported into Canada and iced tea faced low tariffs when imported from Canada into the U.S., so firms created a high-sugar iced “tea” that was then imported into the US and filtered for its sugar!

Bloomberg reports a similar modern workaround. Delta needs new airplanes but now faces steep tariffs on imported European aircraft. As a result, Delta has been stripping European planes of their engines, importing the engines at low tariff rates, and installing them on older aircraft.