Category: Economics

A new critique of RCTs

Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) are the gold standard for evaluating the effects of interventions because they rely on simple assumptions. Their validity also depends on an implicit assumption: that the research process itself—including how participants are assigned—does not affect outcomes. In this paper, I challenge this assumption by showing that outcomes can depend on the subject’s knowledge of the study, their treatment status, and the assignment mechanism. I design a field experiment in India around a soil testing program that exogenously varies how participants are informed of their assignment. Villages are randomized into two main arms: one where treatment status is determined by a public lottery, and another by a private computerized process. My design temporally separates assignment from treatment delivery, allowing me to isolate the causal effect of the assignment process itself. I find that estimated treatment effects differ across assignment methods and that these effects emerge even before the treatment is delivered. The effects are not uniform: the control group responds more strongly to the assignment method than the treated group. These findings suggest that the choice of assignment procedure is consequential and that failing to account for it can threaten the interpretation and generalizability of standard RCT treatment effect estimates.

That is the job market paper of Florencia Hnilo, from Stanford, who also does economic history,

Privatizing Law Enforcement: The Economics of Whistleblowing

The False Claims Act lets whistleblowers sue private firms on behalf of the federal government. In exchange for uncovering fraud and bringing the case, whistleblowers can receive up to 30% of any recovered funds. My work on bounty hunters made me appreciate the idea of private incentives in the service of public goals but a recent paper by Jetson Leder-Luis quantifies the value of the False Claims Act.

Leder-Luis looks at Medicare fraud. Because the government depends heavily on medical providers to accurately report the services they deliver, Medicare is vulnerable to misbilling. It helps, therefore, to have an insider willing to spill the beans. Moreover, the amounts involved are very large giving whistleblowers strong incentives. One notable case, for example, involved manipulating cost reports in order to receive extra payments for “outliers,” unusually expensive patients.

On November 4, 2002, Tenet Healthcare, a large investor-owned hospital company, was sued under the False Claims Act for manipulating its cost reports in order to illicitly receive additional outlier payments. This lawsuit was settled in June 2006, with Tenet paying $788 million to resolve these allegations without admission of guilt.

The savings from the defendants alone were significant but Leder-Luis looks for the deterrent effect—the reduction in fraud beyond the firms directly penalized. He finds that after the Tenet case, outlier payments fell sharply relative to comparable categories, even at hospitals that were never sued.

Tenet settled the outlier case for $788 million, but outlier payments were around $500 million per month at the time of the lawsuit and declined by more than half following litigation. This indicates that outlier payment manipulation was widespread… for controls, I consider the other broad types of payments made by Medicare that are of comparable scale, including durable medical equipment, home health care, hospice care, nursing care, and disproportionate share payments for hospitals that serve many low-income patients.

…the five-year discounted deterrence measurement for the outlier payments computed is $17.46 billion, which is roughly nineten times the total settlement value of the outlier whistleblowing lawsuits of $923 million.

[Overall]…I analyze four case studies for which whistleblowers recovered $1.9 billion in federal funds. I estimate that these lawsuits generated $18.9 billion in specific deterrence effects. In contrast, public costs for all lawsuits filed in 2018 amounted to less than $108.5 million, and total whistleblower payouts for all cases since 1986 have totaled $4.29 billion. Just the few large whistleblowing cases I analyze have more than paid for the public costs of the entire whistleblowing program over its life span, indicating a very high return on investment to the FCA.

As an aside, Leder-Luis uses synthetic control but allows the controls to come from different time periods. I’m less enthused by the method because it introduces another free parameter but given the large gains at small cost from the False Claims Act, I don’t doubt the conclusion:

The results of this analysis suggest that privatization is a highly effective way to combat fraud. Whistleblowing and private enforcement have strong deterrence effects and relatively low costs, overcoming the limited incentives for government-conducted antifraud enforcement. A major benefit of the False Claims Act is not just the information provided by the whistleblower but also the profit motive it provides for whistleblowers to root out fraud.

Why did the colonists hate taxes so much?

The evidence becomes overwhelming that Americans opposed seemingly light taxes, not because they were paranoid, but because the taxes were charged in silver bullion, a money few colonists used on a regular basis and most never had. Thomas Paine had outlined the logic of resistance in June 1780. “There are two distinct things which make the payment of taxes difficult; the one is the large and real value of the sum to be paid, and the other is the scarcity of the thing in which the payment is to be made.”…Adam Gordon, an MR for Aberdeenshire who was traveling in Virginia in 1765, wrote that he was “at a loss to find how they,” some of the wealthiest colonists in the New World, Virginia’s slave-driving tobacco planters, “will find Specie, to pay the Duties last imnosed on them by the Parliament.”

That is from the new and excellent Money and the Making of the American Revolution, by Andrew David Edwards.

What should I ask Dan Wang?

Yes, I will be doing a podcast with him. Dan first became famous on the internet with his excellent Christmas letters. More recently, Dan is the author of the NYT bestselling book Breakneck: China’s Quest to Engineer the Future.

Here is Dan Wang on Wikipedia, here is Dan on Twitter. I have known him for some while. So what should I ask him?

Are new data centers boosting electricity prices?

But a new study from researchers at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and the consulting group Brattle suggests that, counterintuitively, more electricity demand can actually lower prices. Between 2019 and 2024, the researchers calculated, states with spikes in electricity demand saw lower prices overall. Instead, they found that the biggest factors behind rising rates were the cost of poles, wires and other electrical equipment — as well as the cost of safeguarding that infrastructure against future disasters.

“It’s contrary to what we’re seeing in the headlines today,” said Ryan Hledik, principal at Brattle and a member of the research team. “This is a much more nuanced issue than just, ‘We have a new data center, so rates will go up.’”

North Dakota, for example, which experienced an almost 40 percent increase in electricity demand thanks in part to an explosion of data centers, saw inflation-adjusted prices fall by around 3 cents per kilowatt-hour. Virginia, one of the country’s data center hubs, had a 14 percent increase in demand and a price drop of 1 cent per kilowatt-hour. California, on the other hand, which lost a few percentage points in demand, saw prices rise by more than 6 cents per kilowatt-hour.

Here is the full story, via Cliff Winston.

What should I ask Andrew Ross Sorkin?

Yes, I will be doing a Conversation with him. From Wikipedia:

Andrew Ross Sorkin (born February 19, 1977) is an American journalist and author. He is a financial columnist for The New York Times and a co-anchor of CNBC’s Squawk Box. He is also the founder and editor of DealBook, a financial news service published by The New York Times. He wrote the bestselling book Too Big to Fail and co-produced a movie adaptation of the book for HBO Films. He is also a co-creator of the Showtime series Billions.

In October 2025, Sorkin published 1929: Inside the Greatest Crash in Wall Street History–and How It Shattered a Nation, a new history of the Crash based on hundreds of documents, many unpublished.

Most of all I am interested in his new book, but not only. So what should I ask him?

Are the ACA exchanges unraveling?

After all, that is what economists predicted if the mandate was not tightly enforced. Here is the latest reprt:

Premiums for the most popular types of plans sold on the federal health insurance marketplace Healthcare.gov will spike on average by 30 percent next year, according to final rates approved by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and shown in documents reviewed by The Washington Post.

The higher prices — affecting up to 17 million Americans who buy coverage on the federal marketplace — reflect the largest annual premium increases by far in recent years.

Here is the full article.

Should we worry about AI’s circular deals?

The yet once again on target Noah Smith reports:

As far as I can tell, there are two main fears about this sort of deal. The first is that the deals will artificially inflate companies’ revenue, tricking investors into overvaluing their stock or lending them too much money. The second is that the deals increase systemic risk by tying all of the AI companies’ fortunes to each other.

Let’s start with the first of these risks. The question here is whether AI’s circular deals are an example of round-tripping or vendor financing.

Suppose two startups — let’s call them Aegnor and Beleg2 — secretly agree to inflate each other’s revenue. Aegnor buys ad space on Beleg’s website, and Beleg buys ad space on Aegnor’s website. Both companies’ revenues go up. They’re not making any profits, and they’re not generating any cash flows, because the money is just changing hands back and forth. But if investors are looking for companies with “traction”, they might see Aegnor and Beleg’s topline revenue numbers go up. If they fail to dig any deeper, they might give both companies a bunch of investment money that they didn’t earn. This is called “round-tripping”, and it happened occasionally during the dotcom boom.

Now what I just described is completely illegal, because the companies colluded in secret. But you can also have something a little similar happen by accident, in a perfectly legal way. If there are a bunch of startups whose business model is selling to other startups, you can get some of the “round-tripping” effect without any collusion.

On the other hand, it’s perfectly normal and healthy for, say, General Motors to lend its customers the money they use to buy GM cars. In fact, GM has a financing arm specifically to do this. This is called vendor finance. It’s perfectly legal and commonplace, and most people think there’s nothing wrong with it. The transaction being financed — a customer buying a car — is something we know has value. People really do want cars; GM Financial helps them get those cars.

So the question is: Are the AI industry’s circular deals more like round-tripping, or are they more like vendor finance? I’m inclined to say it’s the latter.

Noah stresses that the specifics of these deals are widely reported, and no serious investors are being fooled. I would note a parallel with horizontal or vertical integration, which also can have a financing element. Except that here corporate control is not being exchanged as part of the deal. “I give him some of my company, he gives me some of his — my goodness that is circular must be some kind of problem there!”…just does not make any sense.

Who Pays for Tariffs Along the Supply Chain?

This paper examines the effects of tariffs along the supply chain using product-level data from a large U.S. wine importer in the context of the 2019-2021 U.S. tariffs on European wines. By combining confidential transaction prices with foreign suppliers and U.S. distributors as well as retail prices, we trace price impacts along the supply chain, from foreign producers to U.S. consumers. Although pass-through at the border was incomplete, our estimates indicate that U.S. consumers paid more than the government received in tariff revenue, because domestic markups amplified downstream price effects. The dollar margins per bottle for the importer contracted, but expanded for distributors/retailers. Price effects emerge gradually along the chain, taking roughly one year to materialize at the retail level. Additionally, we find evidence of tariff engineering by the wine industry to avoid duties, leading to composition-driven biases in unit values in standard trade statistics.

That is from a new NBER working paper by

Prediction Markets Are Very Accurate

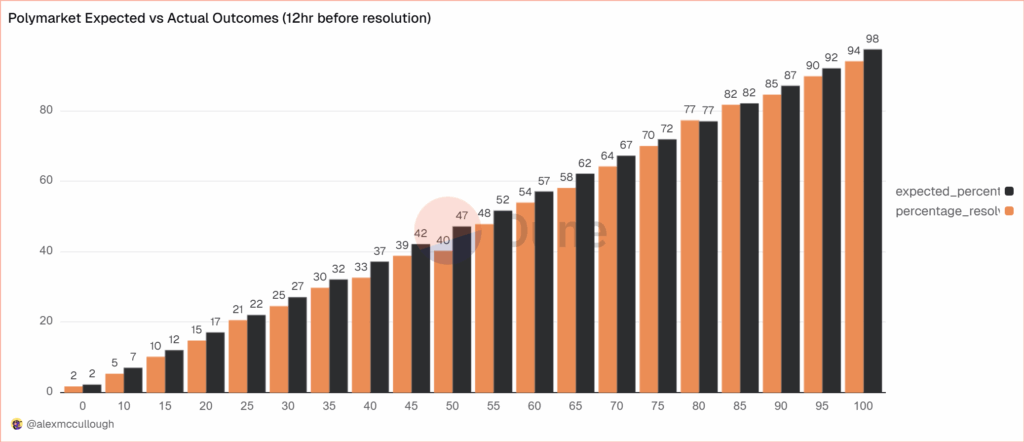

alexmccullough at Dune has a very good post on the accuracy of Polymarket prediction markets. First, how do we measure accuracy? Suppose a prediction market predicts an event will happen with p=.7, i.e. a 70% probability. The event happens. How do we score this prediction? A common method is the Brier Score which is the mean squared difference from the actual outcome. In this case the Brier Score is (0.70−1)2 = 0.09. Notice that if the prediction market had predicted the event would have happened with 90% probability, a better prediction, then the Brier Score would have been (0.90−1)2 = 0.01 a lower number. If the event had not happened then the Brier Score for a 70% prediction would have been (0.70−0)2 = 0.49, a higher number. Thus, a lower Brier Score is better.

Across some 90,000 predictions the Polymarket Brier Score for a 12 hour ahead prediction is .0581. As Alex notes:

A brier score below 0.125 is good, and below 0.1 is great. Polymarket’s total score is excellent, and puts it on par with the best prediction model’s in existence… Sports betting lines tend to average a brier score of between .18-.22.

Brier Scores have been widely used to measure weather forecasts. A state of the art 12 hour ahead forecast of rain, for example, might have a Brier Score of .0.05 – 0.12 so if Polymarket suggest a metaphorical umbrella you would be wise to listen.

Moreover, highly liquid markets are even more accurate.

Even markets with low liquidity have good brier scores below 0.1, but markets with more than $1m in total trading volume have scores of 0.0256 12 hours prior to resolution and 0.0159 a day prior. It’s hard to overstate how impressive that is.

There are, however, some small but systematic errors. The following bar chart splits events into 20 buckets of 5% each so the first bucket covers events that were predicted to happen 0-5% of the time and the last bucket covers events that were predicted to happen 95-100% of the time. The black bar gives the predicted probability, the orange bar the actual frequencies. As expected, events which are predicted to happen more often do happen more often with a very nice progression. Note, however, that the predicted probability is almost always slightly higher than the actual frequency. This means that people are paying a bit too much. It’s unclear whether this is due to market design issues such as the greater difficult of shorting or something about the Automated Market Makers or due to psychological factors such as favorite bias. Thus, some room for improvement but very impressive overall.

Some further new negative results on minimum wage hikes

We study how exposure to scientific research in university laboratories influences students’ pursuit of careers in science. Using administrative data from thousands of research labs linked to student career outcomes and a difference-in-differences design, we show that state minimum wage increases reduce employment of undergraduate research assistants in labs by 7.4%. Undergraduates exposed to these minimum wage increases graduate with 18.1% fewer quarters of lab experience. Using minimum wage changes as an instrumental variable, we estimate that one fewer quarter working in a lab, particularly early in college, reduces the probability of working in the life sciences industry by 2 percentage points and of pursuing doctoral education by 7 percentage points. These effects are attenuated for students supported by the Federal Work-Study program. Our findings highlight how labor market policies can shape the career paths of future scientists and the importance of budget flexibility for principal investigators providing undergraduates with research experience.

That is from a new working paper by Ina Ganguli and Raviv Murciano-Goroff.

The Peter Principle and exploiting overconfident workers

This paper studies a long-term employment relationship with an overconfident worker who updates his beliefs using Bayes’ rule. Once the worker has proven to be a good match, exploitation opportunities disappear. Then, it may be optimal to either end the relationship or promote/transfer the worker to a different role, especially if the new position offers fresh opportunities to exploit his overconfidence. In doing so, we offer a novel microfoundation for the “Peter Principle,” rooted in this dynamic of overconfidence exploitation. Our analysis addresses key limitations in previous explanations, particularly those related to the findings of Benson et al. (2019), where the Peter Principle was observed among highly confident workers.

Look at it this way: you can always promise the worker, at each new switch, a career trajectory that probably he or she will not be able to attain. So you boost them in the hierarchy, with such promises, they are incompetent for the new roles they receive, but you pay them in promised trajectory rather than cold hard cash. That is from Matthias Fahn and Nicholas Klein, now out in the Journal of Labor Economics. Offer them a deanship now, or at least chair of the department. Via the excellent Kevin Lewis.

Ads as cues

Why do we see both advertising and powerful consumer habits for well-known and intrinsically similar brands? We offer an explanation based on the idea that, as in Bordalo et al. (2020), a consumer is more likely to demand a good if she recalls the pleasure it gave her in the past. In turn, the consumer is more likely to recall goods that are consumed more frequently and more similar to cues, subject to interference from other goods. Our model yields context-dependent brand habits where ads work as memory cues. It predicts that ads: i) are more effective for more habitual consumers and ii) exhibit spillovers, within and across products, that are stronger for more habitual consumers and for goods with more similar ads. Using data from NielsenIQ and Nielsen we find support for these predictions in 20 undifferentiated and highly advertised product categories. Memory offers new insights on how advertising affects market competition and consumer welfare.

That is from a new paper by Pedro Bordalo, Giovanni Burro, Nicola Gennaioli, Gad Nacamulli and Andrei Shleifer.

Will there be a Coasean singularity?

By

AI agents—autonomous systems that perceive, reason, and act on behalf of human principals—are poised to transform digital markets by dramatically reducing transaction costs. This chapter evaluates the economic implications of this transition, adopting a consumer-oriented view of agents as market participants that can search, negotiate, and transact directly. From the demand side, agent adoption reflects derived demand: users trade off decision quality against effort reduction, with outcomes mediated by agent capability and task context. On the supply side, firms will design, integrate, and monetize agents, with outcomes hinging on whether agents operate within or across platforms. At the market level, agents create efficiency gains from lower search, communication, and contracting costs, but also introduce frictions such as congestion and price obfuscation. By lowering the costs of preference elicitation, contract enforcement, and identity verification, agents expand the feasible set of market designs but also raise novel regulatory challenges. While the net welfare effects remain an empirical question, the rapid onset of AI-mediated transactions presents a unique opportunity for economic research to inform real-world policy and market design.

I call it “AI for markets in everything.” Here is the paper, and here is a relevant Twitter thread, there is now so much new work for economists to do…

The MR Podcast: Our Favorite Models, Session 2: The Baumol Effect

On The Marginal Revolution Podcast this week we continue discussing some of our favorite models with a whole episode on the Baumol effect (with a sideline into the Linder effect). I say our favorite models, but the Baumol Effect is not one of Tyler’s favorite models! I thought this was a funny section:

TABARROK: When you look at all of these multiple sectors, the repair sector, repairing of clothing, repairing of shoes, repairing of cars, repairing of people, it’s not an accident that these are all the same thing. Healthcare is the repairing of people. Repair services, in general, have gone up because it’s a very labor-intensive area of the economy. It’s all the same thing. That’s why I like the Baumol effect, because it explains a very wide set of phenomena.

COWEN: A lot of things are easier to repair than they used to be, just to be clear. You just buy a new one.

TABARROK: That’s my point. You just buy a new one.

COWEN: It’s so cheap to buy a new one.

TABARROK: Exactly. The new one is manufactured. That’s the whole point, is the new one takes a lot less labor. The repair is much more labor intensive than the actual production of the good. When you actually produce the good, it’s on a factory floor, and you’ve got robots, and they’re all going through da-da-da-da-da-da-da. Repair services, it’s unique.

COWEN: I think you’re not being subjectivist enough in terms of how you define the service. The service for me, if my CD player breaks, is getting a stream of music again. That is much easier now and cheaper than it used to be. If you define the service as the repair, well, okay, you’re ruling out a lot of technological progress. You can think of just diversity of sources of music as a very close substitute for this narrow vision of repair. Again, from the consumer’s point of view, productivity on “repair” has been phenomenal.

TABARROK: That is a consequence of the Baumol effect, not a denial of the Baumol effect. Because of the Baumol effect, repair becomes much more expensive over time, so people look for substitutes. Yes, we have substituted into producing new goods. It works both ways. The new goods are becoming cheaper to manufacture. We are less interested in repair. Repair is becoming more expensive. We’re more interested in the new goods. That’s a consequence of the Baumol effect.

You can’t just say, “Oh, look, we solved the repair problem by throwing things out. Now we don’t have to worry about repairs.” Yes, that’s because repair became so much more expensive. A shift in relative prices caused people to innovate. I’m not saying that innovation doesn’t happen. One of the reasons that innovation happens is because the relative price of repair services is going up.

COWEN: That’s a minor effect. It’s not the case that, oh, I started listening to YouTube because it became too expensive to repair my CD player. It might be a very modest effect. Mostly, there’s technological progress. YouTube, Spotify, and other services come along, Amazon one-day delivery, whatever else. For the thing consumers care about, which is never what Baumol wanted to talk about. He always wanted to fixate on the physical properties of the goods, like the anti-Austrian he was.

It’s just like, oh, there’s been a lot of progress. It takes the form of networks with very complex capital and labor interactions. It’s very hard to even tease out what is truly capital intensive, truly labor intensive. You see this with the AI companies, all very mixed together. That just is another way of looking at why the predictions are so hard. You can only get the prediction simple by focusing very simply on these nonsubjectivist, noneconomic, physical notions of what the good has to be.

TABARROK: I think there’s too much mood affiliation there, Tyler.

COWEN: There’s not enough Kelvin Lancaster in Baumol.

Here’s the episode. Subscribe now to take a small step toward a much better world: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | YouTube.