Category: History

European Stagnation

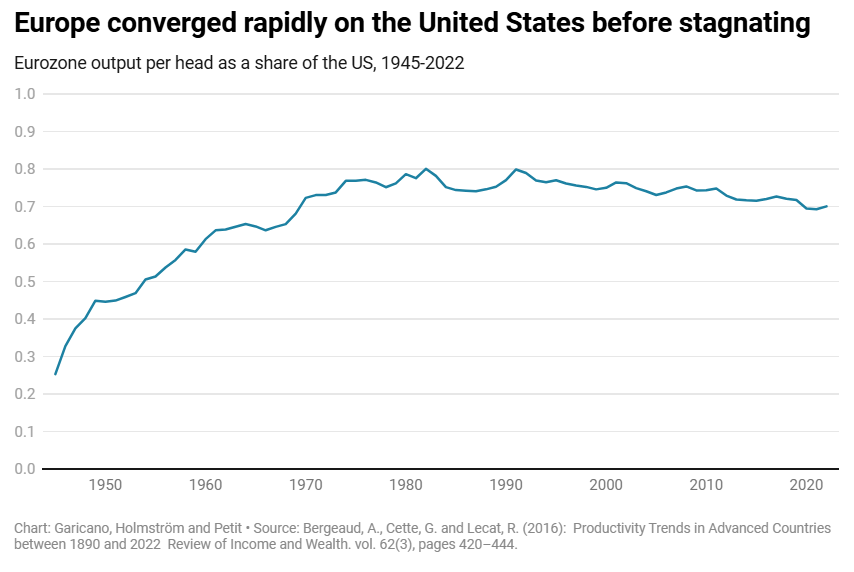

Excellent piece by Luis Garicano, Bengt Holmström & Nicolas Petit.

The continent faces two options. By the middle of this century, it could follow the path of Argentina: its enormous prosperity a distant memory; its welfare states bankrupt and its pensions unpayable; its politics stuck between extremes that mortgage the future to save themselves in the present; and its brightest gone for opportunities elsewhere. In fact, it would have an even worse hand than Argentina, as it has enemies keen to carve it up by force and a population that would be older than Argentina’s is today.

Or it could return to the dynamics of the trente glorieuses. Rather than aspire to be a museum-cum-retirement home, happy to leave the technological frontier to other countries, Europe could be the engine of a new industrial revolution. Europe was at the cutting edge of innovation in the lifetime of most Europeans alive today. It could again be a continent of builders, traders and inventors who seek opportunity in the world’s second largest market.

The European Union does not need a new treaty or powers. It just needs a single-minded focus on one goal: economic prosperity.

I’ve quoted the call to arms but there is much more substantive and deep analysis. Naturally, I approve of this theme “If a product is safe enough to be sold in Lisbon, it should be safe enough for Berlin.” Not the usual fare, read the whole thing.

In defense of Schumpeter

Factories of Ideas? Big Business and the Golden Age of American Innovation (Job Market Paper) [PDF]

This paper studies the Great Merger Wave (GMW) of 1895-1904—the largest consolidation event in U.S. history—to identify how Big Business affected American innovation. Between 1880 and 1940, the U.S. experienced a golden age of breakthrough discoveries in chemistry, electronics, and telecommunications that established its technological leadership. Using newly constructed data linking firms, patents, and inventors, I show that consolidation substantially increased innovation. Among firms already innovating before the GMW, consolidation led to an increase of 6 patents and 0.6 breakthroughs per year—roughly four-fold and six-fold increases, respectively. Firms with no prior patents were more likely to begin innovating. The establishment of corporate R\&D laboratories served as a key mechanism driving these gains. Building a matched inventor–firm panel, I show that lab-owning firms enjoyed a productivity premium not due to inventor sorting, robust within size and technology classes. To assess whether firm-level effects translated into broader technological progress, I examine total patenting within technological domains. Overall, the GMW increased breakthroughs by 13% between 1905 and 1940, with the largest gains in science-based fields (30% increase).

That is the job market paper of Pier Paolo Creanza, who is on the market this year from Princeton.

The first human arrivals in the New World may have sailed from northeast Asia

The first people to migrate to North America may have sailed from north-east Asia around 20,000 years ago. Experts have argued that prehistoric people in Hokkaido, Japan, used similar stone tools to those later found in North America, and suggest that seafarers may have travelled to the continent during the last ice age, bringing this stone technology with them. This adds weight to the theory that the first Americans arrived much earlier than previously thought.

And:

“By [around 30,000 years ago], Upper Palaeolithic seafarers were using sea-going vessels to access some of the outer islands in the Japanese archipelago … and were capable of negotiating the Kuroshio Current, one of the fastest in the world,” Davis and his colleagues write in their paper, published in October in the journal Science Advances. “This suggests that such experienced seafarers may also have been capable of handling adverse Pacific coastal currents.”

Nonetheless, the team also suggest that the journey could have happened at a much slower pace. In this reconstruction, the prehistoric seafarers gradually followed a route along the Pacific coast.

Here is the full story. I have long wondered why, every now and then, in Japan I see a person who looks a great deal like a “Native American.”

Notes on Maputo (Mozambique)

An excellent piece by Joseph Levine, do read the whole thing, here is one excerpt:

Yango is the local ride-hailing app and makes life really easy. It’s a Dubai-based company, split off from Russian Yandex in 2024. Today it’s available as a ride-hailing app in 30+ African countries. Yango rides are really cheap, cheaper than taxis in Freetown or Kanifing, and quality was much higher. A 15 minute ride from my house to my office cost $0.23 on a motorbike, $0.58 in a tuk-tuk, $1.05 in a car, and $1.20 in the equivalent of an Uber Black car. I usually ended up taking the cheaper car option, because you can’t easily sit next to or talk to the driver of a tuk-tuk.

Yango eliminates the ability of taxi drivers to price discriminate. When I walked out of the airport, the taxi drivers wanted ~$20 for the drive to my flat, and I talked them down to $10. On Yango, the drive is $3. My general model of digital marketplaces is that they enable price discrimination (e.g., Uber surge pricing), but in Mozambique it’s the opposite.

Drivers are often professionals working a full-time job, or graduate students. I met a dentist, an engineer working at the new Total plant, several accountants. They also made up the majority of the Muslim Mozambicans whom I met. Most Muslims in Maputo are first- or second-generation immigrants from the northern provinces. One driver, Ismael, grew up on Mozambique Island, about 1,000km north of Maputo; it has a population of 10,000, but most of the young people move to Maputo. He came down to study engineering and now works at a terminal exporting natural gas.

Because I wasn’t on the local mobile money system, I paid for each Yango ride in cash. The car drivers rarely had change (tuk-tuk drivers always did). Alongside rating the driver in the Yango app out of 5 stars, you have to reply yes/no to the question “Did the driver ask for extra cash?” This led to the drivers being very reluctant whenever I told them to keep the change, even when I showed them I had already selected “no”. So we often went around to fruit sellers asking if they would break a twenty.

And:

Mozambique shares a timezone with all the other Southern African countries. As the easternmost country in the timezone, this feels really weird! When I arrived, sunrise was at 5:20am, and sunset about 12 hours later. The early sunsets move business and social events earlier throughout the day. I’m a morning person, but it would usually be considered rude to suggest a 7am in-person meeting. Not here!

The Kalashnikov is a prominent national symbol in Mozambique; it’s on the flag. In particularly touristy areas, hawkers would try to sell me flags, jerseys, banners, scarves with ever-larger AK-47s on them.

Recommended, there should be more travel writing like this.

How Cultural Diversity Drives Innovation

It is hardly possible to overrate the value…of placing human beings in contact with persons dissimilar to themselves, and with modes of thought and action unlike those with which they are familiar….Such communication has always been, and is peculiarly in the present age, one of the primary sources of progress.

Mill had in mind the civilizing force of commerce but the idea is far more general. My colleague Jonathan Schulz with Max Posch and Joe Henrich have a novel and important test of the idea in a paper forthcoming in the JPE: How Cultural Diversity Drives Innovation (WP; SSRN). They show that the more diverse a county, as measured by surnames, the more ideas and the more novel ideas were patented in that county.

We show that innovation in U.S. counties from 1850 to 1940 was propelled by shifts in the local social structure, as captured using the diversity of surnames. Leveraging quasi-random variation in counties’ surnames—stemming from the interplay between historical fluctuations in immigration and local factors that attract immigrants—we find that more diverse social structures increased both the quantity and quality of patents, likely because they spurred interactions among individuals with different skills and perspectives. The results suggest that the free flow of information between diverse minds drives innovation and contributed to the emergence of the U.S. as a global innovation hub.

The influence of Malthus in India?

Public servants frequently fail to implement government policy as intended by principals. I investigate how exposure to economic ideas can alter implementation by government agents, focusing on the influence of Malthusian ideas on British bureaucrats in colonial India. In the Malthusian view, economic distress reduces population growth, raising incomes and ultimately resolving distress without any need for government intervention. Leveraging the death of Malthus in 1834 as a natural experiment, I find that colonial officials who studied under Malthus at a bureaucratic training college implemented less generous fiscal policies in response to rainfall shortages, a proxy for local distress. Across every common relief measure, Malthus-trained officials provided between 0.10 and 0.25 SD less relief than peers trained by Richard Jones, a critic of Malthus. The results offer new evidence concerning how economic ideas shape government policy through their influence on bureaucrats.

That is an abstract from Eric Robertson, who is on the economics job market from University of Virginia.

Technological Change and the Market for Books, 1450-1550

Abstract: This paper considers how movable-type printing’s economic features shaped the early modern book market using product-level data. Building on a lively medieval tradition of manuscript production, Gutenberg’s innovation did not simply reduce costs; it introduced new incentives and constraints that altered both the product’s nature and the market’s structure. First, printing’s business model encouraged the production of shorter and simpler books targeting a poorer and less literate audience. Second, its cost structure led to product differentiation and prolific trade rather than direct competition and localized production, making available a greater variety of products offering diverse information and perspectives. Rather than simply making medieval books cheaper and more abundant, these changes may represent printing technology’s true contribution to European economic development.

That is from the job market paper of Qiyi Charlotte Zhao, who is on the market this year from Stanford. Excellent topic.

The microfoundations of the baby boom?

Between 1936 and 1957, fertility rates in the U.S. increased 62 percent and the maternal mortality rate declined by 93 percent. We explore the effects of changes in maternal mortality rates on white and nonwhite fertility rates during this period, exploiting contemporaneous or lagged changes in maternal mortality at the state-by-year level. We estimate that declines in maternal mortality explain 47-73 percent of the increase in fertility between 1939 and 1957 among white women and 64-88 percent of the increase in fertility among nonwhite women during our sample period.

Here is the full article by Christopher Handy and Katharine Shester, via the excellent Kevin Lewis. Overall, I take this as a negative for the prospect of another, future baby boom? We just cannot make maternity all that much safer, starting from current margins.

My Conversation with the excellent Jonny Steinberg

Here is the audio, video, and transcript. Here is the episode summary:

Tyler considers Winnie and Nelson: Portrait of a Marriage one of the best books of the last decade, and its author Jonny Steinberg one of the most underrated writers and thinkers—in North America, at least. Steinberg’s particular genius lies in getting uncomfortably close to difficult truths through immersive research—spending 350 hours in police ride-alongs, years studying prison gangs and their century-old oral histories, following a Somali refugee’s journey across East Africa—and then rendering what he finds with a novelist’s emotional insight.

Tyler and Jonny discuss why South African police only feel comfortable responding to domestic violence calls, how to fix policing, the ghettoization of crime, how prison gangs regulate behavior through century-old rituals, how apartheid led to mass incarceration and how it manifested in prisons, why Nelson Mandela never really knew his wife Winnie and the many masks they each wore, what went wrong with the ANC, why the judiciary maintained its independence but not its quality, whether Tyler should buy land in Durban, the art scene in Johannesburg, how COVID gave statism a new lease on life, why the best South African novels may still be ahead, his forthcoming biography of Cecil Rhodes, why English families weren’t foolish to move to Rhodesia in the 1920s, where to take an ideal two-week trip around South Africa, and more.

Excerpt:

COWEN: My favorite book of yours again is Winnie and Nelson, which has won a number of awards. A few questions about that. So, they’re this very charismatic couple. Obviously, they become world-historical famous. For how long were they even together as a pair?

STEINBERG: Very, very briefly. They met in early 1957. They married in ’58. By 1960, Mandela was no longer living at home. He was underground. He was on the run. By 1962, he was in prison. So, they were really only living together under the same roof for two years.

COWEN: And how well do you feel they knew each other?

STEINBERG: Well, that’s an interesting question because Nelson Mandela was very, very in love with his wife, very besotted with his wife. He was 38, she was 20 when they met. She was beautiful. He was a notorious philanderer. He was married with three children when they met. He really was besotted with her. I don’t think that he ever truly came to know her. And when he was in prison, you can see it in his letters. It’s quite remarkable to watch. She more and more becomes the center of meaning in his life, his sense of foundation, his sense of self as everything else is falling away.

And he begins to love her more and more, and even to coronate her more and more so that she doesn’t forget him. His letters grow more romantic, more intense, more emotional. But the person he’s so deeply in love with is really a fiction. She’s living a life on the outside. And you see this very troubling line between fantasy and reality. A man becoming deeply, deeply involved with a woman who is more and more a figment of his imagination.

COWEN: Do you think you learned anything about marriage more generally from writing this book?

STEINBERG: [laughs] One of the sets of documents that I came across in writing the book were the transcripts of their meetings in the last 10 years of his imprisonment. The authorities bugged all of his meetings. They knew they were being bugged, but nonetheless, they were very, very candid with each other. And you very unusually see a marriage in real time and what people are saying to each other. And when I read those lines, 10 different marriages that I know passed through my head: the bickering, the lying, the nasty things that people do to one another, the cruelties. It all seemed very familiar.

COWEN: How is it you think she managed his career from a distance, so to speak?

STEINBERG: Well, she was a really interesting woman. She arrived in Johannesburg, 20 years old in the 1950s, where there was no reason to expect a woman to want a place in public life, particularly not in the prime of public life. And she was absolutely convinced that there was no position she should not occupy because she was a woman. She wanted a place in politics; she wanted to exercise power. But she understood intuitively that in that time and place, the way to do that was through a man. And she went after the most powerful rising political activists available.

I don’t think it was quite as cynical as that. She loved him, but she absolutely wanted to exercise power, and that was a way to do it. Once she became Mrs. Mandela, I think she had an enormously aristocratic sense of politics and of entitlement and legitimacy. She understood herself to be South Africa’s leader by virtue of being married to him, and understood his and her reputations as her projects to endeavor to keep going. And she did so brilliantly. She was unbelievably savvy. She understood the power of image like nobody else did, and at times saved them both from oblivion.

COWEN: This is maybe a delicate question, but from a number of things I read, including your book, I get the impression that Winnie’s just flat out a bad person…

Interesting throughout, this is one of my favorite CWT episodes, noting it does have a South Africa focus.

Why did the colonists hate taxes so much?

The evidence becomes overwhelming that Americans opposed seemingly light taxes, not because they were paranoid, but because the taxes were charged in silver bullion, a money few colonists used on a regular basis and most never had. Thomas Paine had outlined the logic of resistance in June 1780. “There are two distinct things which make the payment of taxes difficult; the one is the large and real value of the sum to be paid, and the other is the scarcity of the thing in which the payment is to be made.”…Adam Gordon, an MR for Aberdeenshire who was traveling in Virginia in 1765, wrote that he was “at a loss to find how they,” some of the wealthiest colonists in the New World, Virginia’s slave-driving tobacco planters, “will find Specie, to pay the Duties last imnosed on them by the Parliament.”

That is from the new and excellent Money and the Making of the American Revolution, by Andrew David Edwards.

What should I ask Andrew Ross Sorkin?

Yes, I will be doing a Conversation with him. From Wikipedia:

Andrew Ross Sorkin (born February 19, 1977) is an American journalist and author. He is a financial columnist for The New York Times and a co-anchor of CNBC’s Squawk Box. He is also the founder and editor of DealBook, a financial news service published by The New York Times. He wrote the bestselling book Too Big to Fail and co-produced a movie adaptation of the book for HBO Films. He is also a co-creator of the Showtime series Billions.

In October 2025, Sorkin published 1929: Inside the Greatest Crash in Wall Street History–and How It Shattered a Nation, a new history of the Crash based on hundreds of documents, many unpublished.

Most of all I am interested in his new book, but not only. So what should I ask him?

How the pandemic has changed the world

From Patrick Collison on Twitter:

Maybe a very prosaic observation, but I’ve been reflecting on just how much the pandemic changed the world in ways that are completely unrelated to the pandemic itself. I think I’ve underestimated it ’till now.

In a recent interview, I was struck by the comment that so many of the shops that we associate with the best of France—the poissonneries and the fromageries—closed during the pandemic, to be replaced by take-out pizza shops and the like.

College professors almost uniformly describe big changes in student behavior: lecture attendance and willingness of students to complete reading assignments are both way down.

A UK government official recently told me that British economic statistics have become much less reliable since the pandemic: data on trade, employment, and population is suspect. (The true GDP per capita figures are probably worse than what is indicated by the published data, since the 2021 census is believed to be an undercount.)

In the West, there are far fewer bustling workplaces than there used to be. In recent conversation with a well-traveled friend, he bemoaned how so many cities—places like Madrid, Buenos Aires, and Bali—have lost so much of their erstwhile vibrant nightlife.

Immigration accelerated enormously across many countries, including the US, the UK, Canada, and Australia.

In China, I hear descriptions of how fear, caution, and conservatism have persisted since the COVID lockdowns. (And Western travel to China remains massively depressed.)

Lots of the changes are neutral, or even good. Retail participation in the US stock market almost doubled overnight, say, and has persisted at that elevated rate. Firm creation in the US increased by around 50%, which is probably a very good thing.

Overall, the number of time series (either literal or figurative) that jumped discontinuously during COVID and then didn’t return to baseline is just very striking.

Which are the best historical analogs? Are there any apart from major wars?

I want to read this book!

What should I ask Diarmaid MacCulloch

Yes, I will be doing a Conversation with him. He has a recent book out on the history of sexuality and Christianity, but of course is renowned for a much longer series of books and writings on Christianity, the Reformation, and Tudor British history, just for a start.

Here is his Wikipedia page. So what should I ask him?

*Surviving Rome: The Economic Lives of the Ninety Percent*

By Kim Bowes, this is an excellent book, the best I know of on ordinary economic life in the Roman empire. It also shows a very good understanding of economics, unlike some forays by archeologists. Here is one excerpt:

On the income side, we’ve seen that unskilled wages, which were very low indeed, were also a very bad proxy for income. Wages were usually part of a portfolio of income, a portfolio that all family members contributed to, but one still centered on own production — either farming or textile/artisanal work. Unskilled wages supplemented own-production; they mostly weren’t equivalent to it. Roman wagges, unlike modern wages, can’t be used as a proxy for income.

Gross income from own-production, particularly farming, appears to have been much higher than previously supposed. Rotation strategies practiced by Italian and Egyptian farmers meant that per-hectare outputs were many times greater than alternate fallow models predicted, since outputs included not only wheat but also significant quantities of fodder and animals. In the northwest provinces, where rotation was less common, outputs per hectare were lower but still included some hay and larger animal herds. And every, high settlement densities and shrinking amounts of land would have urged farmers to achieve higher yields — in some places three or more times greater than previously supposed. We can’t be sure they managed this, only that low yields would have been mostly unteanble and that farmers had the tools — rotation, manuring, weeding — to achieve higher ones.

Most working class Romans, by the way, bought their clothing rather than having to make it themselves.

Recommended, you can pre-order it here.

The Economic Geography of American Slavery

What would the antebellum American economy have looked like without slavery? Using new micro-data on the U.S. economy in 1860, we document that where free and enslaved workers live and how much they earn correlates strongly—but differently—with geographic proxies for agricultural productivity, disease, and ease of slave escape. To explain these patterns, we build a quantitative spatial model of slavery, where slaveholders coerce enslaved workers into supplying more labor, capture the proceeds of their labor, and assign them to sectors and occupations that maximize owner profits rather than worker welfare. Combining theory and data, we then quantify how dismantling the institution of slavery affected the spatial economy. We find that the economic impacts of emancipation are substantial, generating welfare gains for the enslaved of roughly 1,200%, while reducing welfare of free workers by 0.7% and eliminating slaveholder profit. Aggregate GDP rises by 9.1%, with a contraction in agricultural productivity counteracted by an expansion in manufacturing and services driven by an exodus of formerly enslaved workers out of agriculture and into the U.S. North.

That is from a new NBER working paper by