Category: Law

This is actually quite a common attitude toward science

Scarlett decided to call for backup.

A few days later, the fourth-grader sent the evidence she’d collected to local police with a letter explaining her investigative methodology and what she was trying to find out: “Dear Cumberland Police department, I took a sample of a cookie and carrots that I left for Santa and the raindeer on christmas eve and was wondering if you could take a sample of DNA and see if Santa is real?”

Here is the full story by Jonathan Edwards, via the excellent Kevin Lewis.

The medical culture that is Britain

Universities have been told they must limit the number of medical school places this year or risk fines, a move attacked as “extraordinary” when the NHS is struggling with staff shortages.

Medical schools have been told to curtail offers to ensure that there is “no risk” of them accepting more would-be doctors than permitted by a government cap, with universities saying they are likely to offer fewer places than normal to sixth-formers this year.

Ministers have been criticised for holding firm to a 7,500 cap on new medical students in England while also acknowledging that a chronic shortage of doctors and nurses is contributing to long delays for NHS treatment.

Robert Halfon, the universities minister, wrote to vice-chancellors last week telling them to limit their offers to sixth-formers, causing frustration among universities, which face fines of £100,000 per student for persistent over-recruitment. Universities say that in the summer, they were forced to reject students for administrative reasons such as submitting vaccine certificates late to stay within permitted numbers.

Here is more from the Times of London (gated). Perhaps Tyrone approves!

The wisdom of Alex Tabarrok

The new AEA policy which requires all data to be legally acquired has costs. As I read it, it would prohibit analysis of say the Panama papers or ProPublica tax data. Satellite data could also be considered questionable in some countries. https://t.co/kQJPL4nwbe

— Alex Tabarrok 🛡️ (@ATabarrok) January 18, 2023

This will in relative terms help the larger, better established researchers, right? And how will it handle GDPR, the right to be forgotten, data storage under EU law, and so on? What is the chance this has all been thought through properly?

Is crypto now underrated?

I appeared on the Bankless crypto podcast, and they sent me these links:

- Youtube – https://youtu.be/ByefgDAFgv8

- Podcast – https://availableon.com/bankless

- Substack Post – https://open.substack.com/pub/banklesspod/p/early-access-why-crypto-is-underrated

The economics of non-competes

That is the topic of my latest Bloomberg column, here is one excerpt:

The value of noncompete clauses is easy to illustrate. Say you run a hedge fund. Many members of your trading team will have partial access to your firm’s trading secrets, and if they leave they can take those secrets with them. In the absence of noncompete agreements, firms would be more likely to “silo” information — becoming less efficient and less able to pay higher wages.

Nondisclosure agreements for workers in such positions are common, but they are difficult to enforce — making noncompete agreements more relevant. How exactly might you find out if some other newly created hedge fund is using your trading algorithms?

Or say you are a sales company with a customer list, or a nonprofit with a donor list. An employee who sees those lists could use that information to start a competing business, or take that information to competitors. It seems reasonable in such cases to restrict the ability of employees to “jump ship.”

If noncompetes are banned outright, to repeat, the effect will be less information-sharing within the company. New workers in particular, who have not demonstrated their long-term loyalty, will have a hard time getting access to information and getting ahead. More senior employees will have the advantage, hardly a formula for boosting economic opportunity.

I call for federalism and piecemeal regulation of the practice, not the all-out federal ban proposed by Lina Khan’s once again overreaching FTC.

Testing Freedom

In the latest Discourse Magazine I discuss the FDA’s long-standing fear and antipathy toward personalized medical tests and how this violates the 1st Amendment.

In 1972, the FDA confiscated thousands of home pregnancy tests, declaring that they were “drugs” meant to diagnose a “disease” and thus fell under the FDA’s regulatory dominion. The case went to the U.S. District Court for the District of New Jersey, and Judge Vincent P. Biunno ruled that the FDA had overstepped. “Pregnancy,” he said, “is a normal physiological function of all mammals and cannot be considered a disease … a test for pregnancy, then, is not a test for the diagnosis of disease. It is no more than a test for news….” As a result of Judge Biunno’s ruling, home pregnancy tests are easily available today from pharmacies, grocery stores and online shops without a prescription.

These days, debates over home pregnancy tests from the 1970s seem anachronistic and paternalistic. Yet the same paternalistic arguments appear again and again with every new testing technology. In the late 1980s, for example, the FDA simply declared that it would not approve at-home HIV tests, regardless of their safety or efficacy. As with pregnancy tests, the concern was that people could not be trusted with information about their own bodies…the first rapid at-home HIV test was developed and submitted to the FDA in 1987 [but] it took 25 years before the FDA would approve these tests. (Now, you can easily buy such a test on Amazon.)

…The FDA has a vital role in ensuring that tests are clinically accurate—tests should do what they say they do. Tests don’t need to be perfectly accurate to be useful (think of thermometers, personality tests and tire pressure gauges), but if a test advertises that it measures HDL cholesterol, it should do that within the tolerances the firm promises. The FDA has the technical knowledge to ensure that tests work, and that’s a skill that Americans value from the agency.

What Americans don’t want is to be told they can’t handle the truth. Yet when it came to at-home tests such as pregnancy tests, HIV tests and genetic tests, that’s exactly the reasoning the FDA used—and continues to use—to suppress information. The FDA should ensure that tests are safe, but “safety” means physical safety. The FDA may not declare a product unsafe because it might produce dangerous knowledge. Patients have a right to know about their own bodies. Our antibodies, ourselves. The FDA has authority over drugs and devices but not over patients.

Judge Biunno had it right back in 1972 when he said that diagnostic tests produce “news.” Test results, therefore, are a type of speech that fall under the First Amendment right to freedom of speech. The Supreme Court has repeatedly rejected restrictions on freedom of speech based on “a fear that people would make bad decisions if given truthful information”; thus, FDA restrictions on tests based on such fears are unconstitutional. The question of whether consumers will respond “safely” to test results is no more relevant to the FDA’s regulatory authority than the question of whether readers will respond safely to political news published in The New York Times. The FDA does not have the constitutional authority to regulate news.

Why did the gender wage gap stop narrowing?

During the 1980s, the wage gap between white women and white men in the US declined by approximately 1 percentage point per year. In the decades since, the rate of gender wage convergence has stalled to less than one-third of its previous value. An outstanding puzzle in economics is “why did gender wage convergence in the US stall?” Using an event study design that exploits the timing of state and federal family-leave policies, we show that the introduction of the policies can explain 94% of the reduction in the rate of gender wage convergence that is unaccounted for after controlling for changes in observable characteristics of workers. If gender wage convergence had continued at the pre-family leave rate, wage parity between white women and white men would have been achieved as early as 2017.

That is from a new NBER working paper by Peter Q. Blair and Benjamin Posmanick. Might the gender wage gap be one economics topic where a naive, mood-affiliated view on it best predicts a bunch of other bad views on totally separate topics?

How much did pre-ACA Medicaid expansions matter?

This paper examines the impact of Medicaid expansions to parents and childless adults on adult mortality. Specifically, we evaluate the long-run effects of eight state Medicaid expansions from 1994 through 2005 on all-cause, healthcare-amenable, non-healthcare-amenable, and HIV-related mortality rates using state-level data. We utilize the synthetic control method to estimate effects for each treated state separately and the generalized synthetic control method to estimate average effects across all treated states. Using a 5% significance level, we find no evidence that Medicaid expansions affect any of the outcomes in any of the treated states or all of them combined. Moreover, there is no clear pattern in the signs of the estimated treatment effects. These findings imply that evidence that pre-ACA Medicaid expansions to adults saved lives is not as clear as previously suggested.

That is a new NBER working paper from Charles J. Courtemanche, Jordan W. Jones, Antonios M. Koumpias, and Daniela Zapata.

Here are some relevant pictures. Now, would you expect subsequent Medicaid expansions to have higher, lower, or the same marginal value?

Do pay transparency laws raise wages?

It seems not:

Labour advocates champion pay-transparency laws on the grounds that they will narrow pay disparities. But research suggests that this is achieved not by boosting the wages of lower-paid workers but by curbing the wages of higher-paid ones. A forthcoming paper by economists at the University of Toronto and Princeton University estimates that Canadian salary-disclosure laws implemented between 1996 and 2016 narrowed the gender pay gap of university professors by 20-30%. But there is also evidence that they lower salaries, on average. Another paper by professors at Chapel Hill, Cornell and Columbia University found that a Danish pay-transparency law adopted in 2006 shrank the gender pay gap by 13%, but only because it curbed the wages of male employees. Studies of Britain’s gender-pay-gap law, which was implemented in 2018, have reached similar conclusions.

Another misconception about pay-transparency laws is that they strengthen the bargaining power of workers. A recent paper by Zoe Cullen of Harvard Business School and Bobby Pakzad-Hurson of Brown University analysed the effects of 13 state laws passed between 2004 and 2016 that were designed to protect the right of workers to ask about the salaries of their co-workers. The authors found that the laws were associated with a 2% drop in wages, an outcome which the authors attribute to reduced bargaining power. “Although the idea of pay transparency is to give workers the ability to renegotiate away pay discrepancies, it actually shifts the bargaining power from the workers to the employer,” says Mr Pakzad-Hurson. “So wages are more equal,” explains Ms Cullen, “but they’re also lower.”

Here is more from The Economist.

How long does a Roman emperor last for?

Of the 69 rulers of the unified Roman Empire, from Augustus (d. 14 CE) to Theodosius (d. 395 CE), 62% suffered violent death. This has been known for a while, if not quantitatively at least qualitatively. What is not known, however, and has never been examined is the time-to-violent-death of Roman emperors. This work adopts the statistical tools of survival data analysis to an unlikely population, Roman emperors, and it examines a particular event in their rule, not unlike the focus of reliability engineering, but instead of their time-to-failure, their time-to-violent-death. We investigate the temporal signature of this seemingly haphazardous stochastic process that is the violent death of a Roman emperor, and we examine whether there is some structure underlying the randomness in this process or not. Nonparametric and parametric results show that: (i) emperors faced a significantly high risk of violent death in the first year of their rule, which is reminiscent of infant mortality in reliability engineering; (ii) their risk of violent death further increased after 12 years, which is reminiscent of wear-out period in reliability engineering; (iii) their failure rate displayed a bathtub-like curve, similar to that of a host of mechanical engineering items and electronic components. Results also showed that the stochastic process underlying the violent deaths of emperors is remarkably well captured by a (mixture) Weibull distribution.

That is from a new paper by Joseph Homer Saleh. Via Patrick Moloney. And here are new results on why Roman concrete was so much more durable than the emperors.

Beware the dangers of crypto regulation

That is the topic of my latest Bloomberg column, here is one bit:

No matter how strong the temptation, we should not overregulate.

Begin with two central facts. First, there are numerous ways for small and large investors to lose their money, including by investing in risky equities. Regulating crypto won’t end that danger. Second, despite being one of the largest financial frauds in history, FTX has not created systemic financial risk, which should be the main concern of regulators. And market forces already have made the risk from crypto much smaller: At the peak of crypto values in late 2021, crypto assets had a total value of about $2 trillion; as of this writing, that figure is about $845 billion.

And:

Crypto regulation is not easy to do well. If crypto institutions are treated like regular depository institutions, requiring heavy layers of capital and lots of legal staffing, crypto innovation is likely to dwindle. Such innovation has been more the province of eccentric geniuses than of mainstream regulated institutions. It is hard to imagine Satoshi Nakamoto or Vitalik Buterin at Goldman Sachs.

And what exactly should be the goal of crypto regulation? To make stablecoins truly stable in nominal value? Is that even possible? Or to encourage market participants to see those assets as inherently fluctuating in value?

Neither academic research nor market experience offers clear answers. With systemic risk currently low, perhaps it is better to wait and learn more before moving ahead with regulation. And on a purely practical level, very few members of Congress (or their staff members) have a good working knowledge of crypto and all of its current wrinkles and innovations.

There is much more of value at the link.

Lead and violence: all the evidence

Kevin Drum offers a response to a recent meta-study on the link between lead and violence, blogged by me here.

I’ll take this moment to explain why the lead-violence connection never has sat that well with me.

Let’s say we are trying to explain why 2022 America is richer than the Stone Age. We could cite “incentives, policy, and culture,” noting that any accumulated stock of wealth also came from these (and possibly other) factors. You might disagree about which policies, or which cultural features of modernity, and so on, but the answer to the question pretty clearly lies in that direction.

Now let us say we are trying to explain why America today is richer than Albania today. You would do just fine to start with “incentives, policy, and culture.” You could add in some additional factors, such as superior natural resources, but you would be on the same track as with the Stone Age comparison. You would not have to summon up an entirely new theory.

Why is Nashville richer than Chattanooga? Again, start with “incentives, policy, and culture,” noting you might need again supplementary factors.

Broadly the same theory is applying to all of these different comparisons. Across time, across space, across countries, and across cities. There is something about this broad unity that is methodologically satisfying, and it helps confirm our view that we are on the right track in our inquiries.

Now consider the lead-crime connection. Insofar as you elevate the connection as very strong, you are tossing out the chance of achieving that kind of unity.

Why was violent crime so often more frequent in earlier periods of human history? It wasn’t lead, at least not for most periods, perhaps not for any of the much earlier periods.

Why was there more peace in Ethiopia five years ago than in the last few years? Again, whatever the reasons it wasn’t a change in lead exposure.

Why is the murder rate in Haiti today much higher than during the Duvaliers? Again, no one thinks the answer has much to do with changes in lead exposure. Mainly it is because political order has collapsed, and the country is ruled by gangs rather than by an autocratic tyranny.

How about the violence rate in the very peaceful parts of Africa compared to the very violent parts? Again, lead is rarely if ever going to be the answer to that one.

So we know in the true, overall model big changes in violence can happen without lead exposure being the driving force. Very big changes. In fact those big changes in violence rates, without lead being a major factor, happen all the time.

And many of those big changes are mysterious in their causes. It really isn’t so simple to explain why different parts of Africa have different murder rates, often by very significant amounts. You can hack away at the problem (e.g, Kenya and Tanzania have very different histories), but there is no simple “go to” theory. Furthermore, since both violence and peace often feed upon themselves, in a “broken windows” increasing returns sort of way, the initial causes behind big differences in violence outcomes might sometimes be fairly slight and hard to find.

That to my mind makes “the true model” somewhat biased against lead being a major factor in changes in violence rates. In the broader scheme of things, lead exposure seems to be a supplementary factor rather than a major factor. It doesn’t rule out lead as a major factor, either logically or statistically, if you wish to explain why U.S. violence fell from the 1960s to today. But the true model has a lot of non-lead, major shifts in violence, often unexplained or hard to explain.

Addendum: I am also surprised by Kevin’s comment that there isn’t likely to be much publication bias in lead-violence studies. I take publication bias to be a default assumption, namely the desire to show a positive result to get published. That hardly seems unlikely to me at all. And in this particular case there is even a particular political reason to wish to pin a lot of the blame on lead exposure. Correctly or not, people on the Left are much more likely to elevate lead exposure as a cause of social problems.

And to repeat myself, just to be perfectly clear, it strikes me as unlikely that the effect of lead exposure on violence in zero is the last seventy years of the United States.

The EU’s carbon tariffs

That is the topic of my latest Bloomberg column. Here is one excerpt, starting with the basic idea:

Importers would have to register to receive authorization to import goods, and they would pay a tax per ton of carbon dioxide produced. These fees are intended to match those already applied within the EU, which are currently about 90 euros per ton. The policy is also intended to place EU industry on a more competitive footing and encourage foreign countries to adopt greener energy policies.

But will it work?:

But would it? Economic changes take place at the margin, and currently the EU is engaged in substitution toward coal, a very dirty energy source.

In light of that reality, consider the proposed tariffs as having (at least) two effects. First, they will push some production out of foreign nations and into the EU. Second, they will induce some foreign nations to move to greener energy sources over time, to avoid the tax.

In the short run, the first effect dominates: The tariffs will lead to more coal use and a dirtier energy supply.

Be suspicious of green energy policies which at first make the problem worse. However promising the longer-run promises may sound, there is always the risk that bureaucratic inertia will intervene and the short-run policy effects will dominate.

The rationale for the beneficial long-run effects of the tariffs is that foreign nations, including some relatively poor nations such as India, will move toward greener energy at a more rapid pace. That might happen. But look at the EU itself over the past year. Its energy prices went up, due to the Russian attack on Ukraine, but the EU did not move toward greener energy, such as more nuclear or wind power. It moved toward dirtier energy, in part because domestic interest groups opposed the more beneficial adjustments.

So, despite about as strong an incentive as possible — a war — the EU made the harmful rather than the beneficial adjustment. Now it is expecting that much poorer nations, often with worse governance structures, to do better. Not only is this naïve, but it is also protectionist.

And this:

Even the positive long-run effects are up for grabs. On one hand, the tariff hike provides an incentive to move toward greener energy. On the other, it makes the exporting nations poorer than they otherwise would be. Poorer nations tend to be less interested in improving their environments, as clean environments are largely a luxury good. And extreme poverty worsens other global problems, including issues stemming from migration. Should EU policy make it more difficult for Africa to industrialize?

One also has to wonder whether the promise of lower tariffs in return for greener energy is credible. Once protectionist measures are in place, they are hard to reverse. The EU would be reaping tariff revenue, and domestic EU industries would be receiving trade protection. Any reclassification of the imports as fundamentally “greener” would require an investigation across borders and clearance through multiple levels of bureaucracy. Such changes will not be easy to accomplish, especially in an era increasingly enamored of trade restrictions.

Worth a ponder. EU coal consumption has been up over the last two years. And what is relevant here is energy supply at the margin.

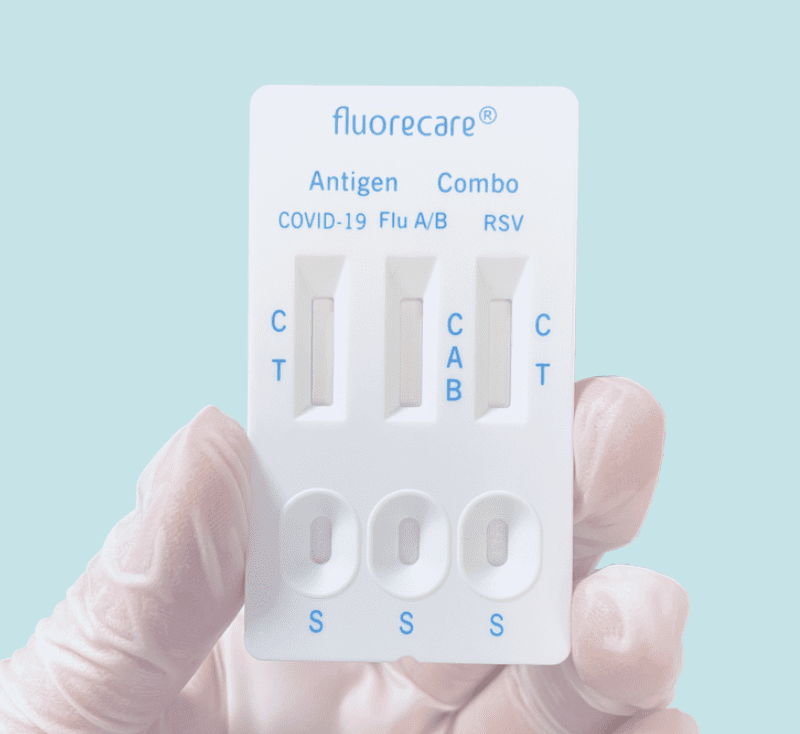

Combination Rapid Tests

Once again, the US is behind on at-home rapid antigen tests–this time on combination tests that let you test for COVID, Influenza, and RSV all at once. These tests are widely available in Europe but have not been approved by the FDA. Rapid flu tests especially are potentially very useful in assigning appropriate treatment and reducing the overuse of antibiotics.

Does reducing lead exposure limit crime?

These results seem a bit underwhelming, and furthermore there seems to be publication bias, this is all from a recent meta-study on lead and crime. Here goes:

Does lead pollution increase crime? We perform the first meta-analysis of the effect of lead on crime by pooling 529 estimates from 24 studies. We find evidence of publication bias across a range of tests. This publication bias means that the effect of lead is overstated in the literature. We perform over 1 million meta-regression specifications, controlling for this bias, and conditioning on observable between-study heterogeneity. When we restrict our analysis to only high-quality studies that address endogeneity the estimated mean effect size is close to zero. When we use the full sample, the mean effect size is a partial correlation coefficient of 0.11, over ten times larger than the high-quality sample. We calculate a plausible elasticity range of 0.22-0.02 for the full sample and 0.03-0.00 for the high-quality sample. Back-ofenvelope calculations suggest that the fall in lead over recent decades is responsible for between 36%-0% of the fall in homicide in the US. Our results suggest lead does not explain the majority of the large fall in crime observed in some countries, and additional explanations are needed.

Here is one image from the paper:

The authors on the paper are Anthony Higney, Nick Hanley, and Mirko Moroa. I have long been agnostic about the lead-crime hypothesis, simply because I never had the time to look into it, rather than for any particular substantive reason. (I suppose I did have some worries that the time series and cross-national estimates seemed strongly at variance.) I can report that my belief in it is weakening…