Category: Media

Four Thousand Years of Egyptian Women Pictured

In an excellent, deep-dive Alice Evans looks at patriarchy in Egypt using pictures drawn from four thousand years of history. Here are three examples.

In an excellent, deep-dive Alice Evans looks at patriarchy in Egypt using pictures drawn from four thousand years of history. Here are three examples.

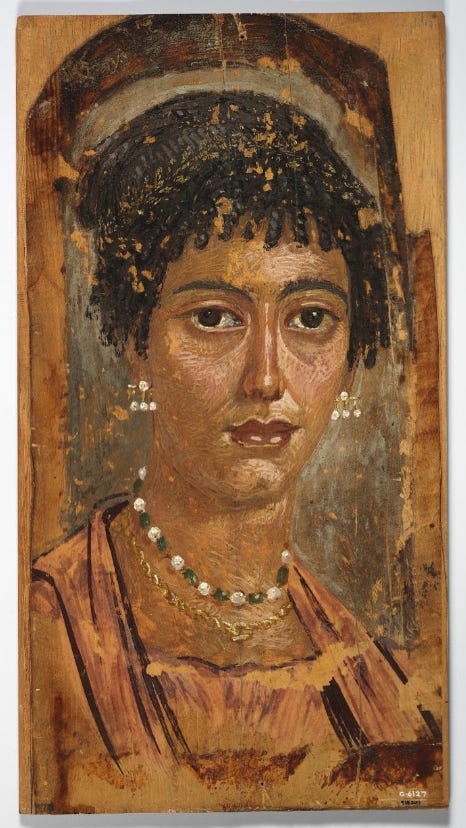

A wealthy woman, shown at right circa 116 CE. Unveiled, immodest, looking out at the world. A person to be reckoned with.

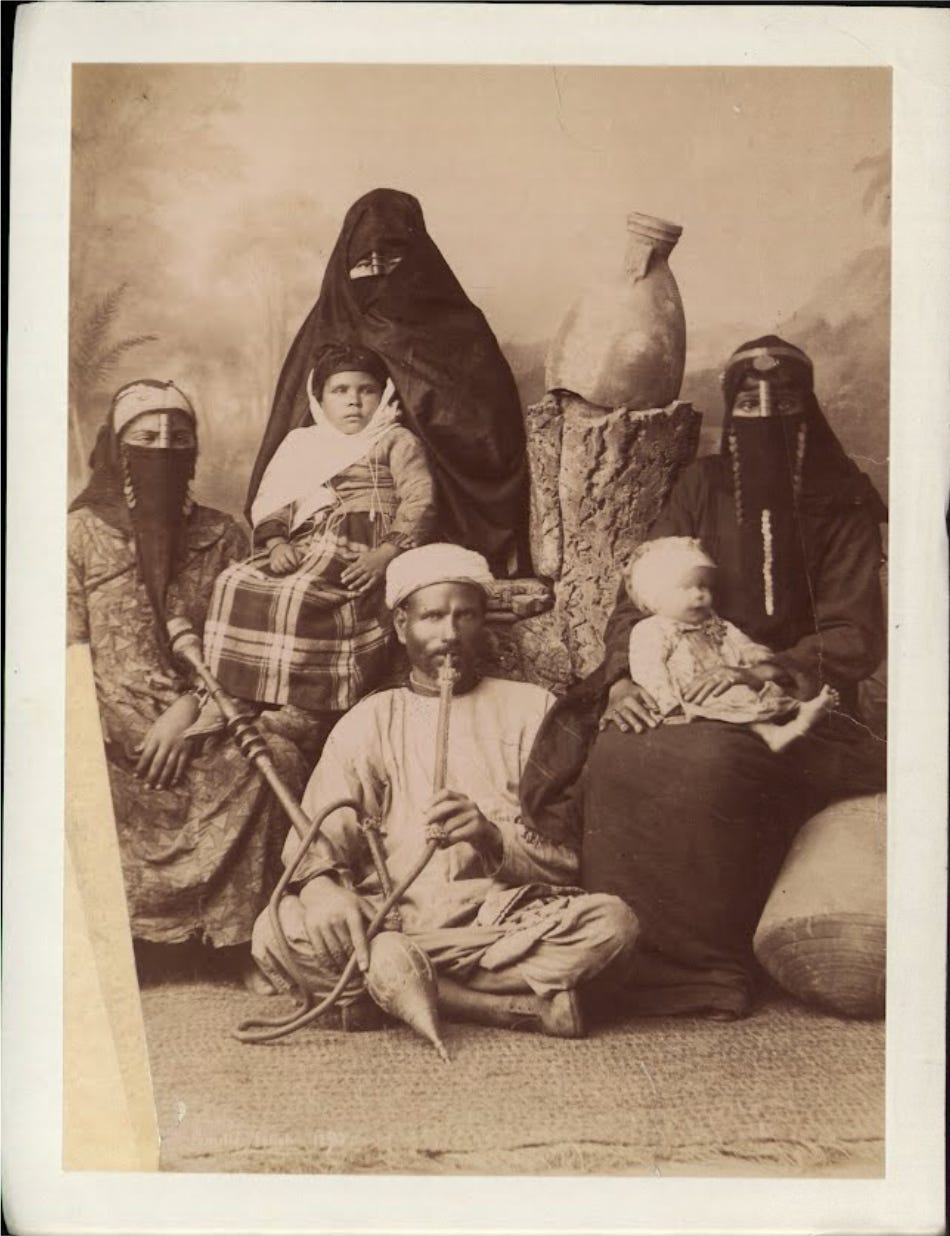

After the Arab conquests, pictures of people in general disappear, and there are no books written by women. With the dawn of photography in the 19th century we see (at left) what was probably typical, veiled women, and very few women on the street.

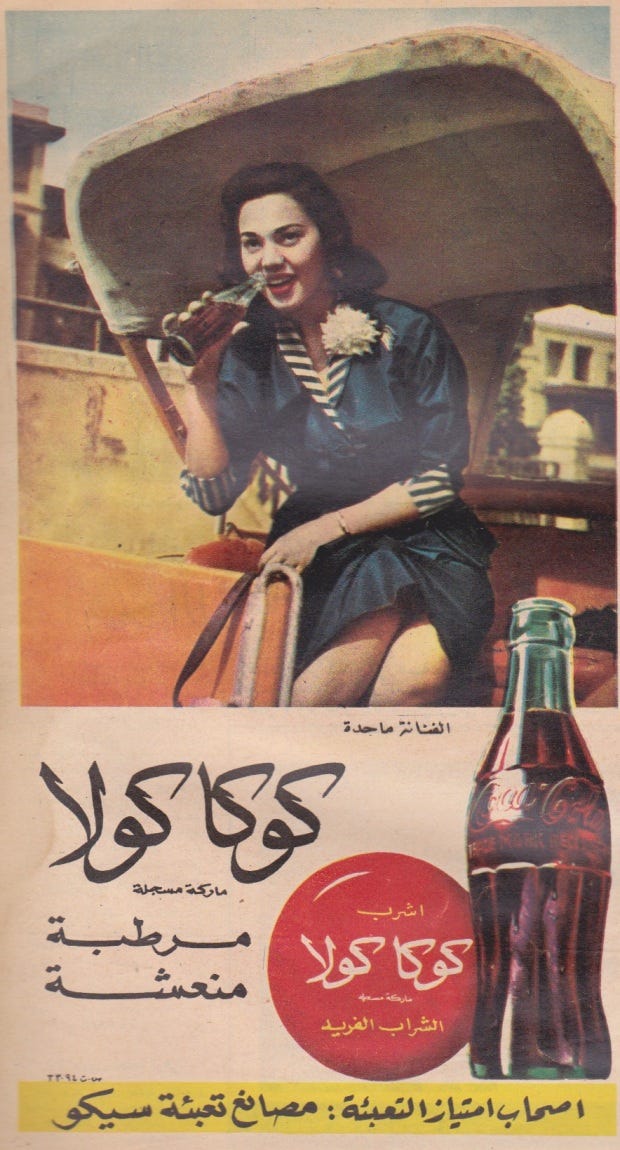

In the 1950s and 1970s we see a remarkable revitalization and liberalization noted most evidently in advertisements (advertisers being careful not to offend). Note the bare legs and the fact that many advertisements are directed at women (below)

This period culminates in a remarkable video unearthed by Evans of Nasser in 1958 openly laughing at the idea that women should or could be required to veil in public. Worth watching.

In the 1980s, however, it all ends.

Egyptians who came of age in the 1950s and ‘60s experienced national independence, social mobility and new economic opportunities. By the 1980s, economic progress was grinding down. Egypt’s purchasing power was plummeting. Middle class families could no longer afford basic goods, nor could the state provide.

As observed by Galal Amin,

“When the economy started to slacken in the early 1980s, accompanied by the fall in oil prices and the resulting decline in work opportunities in the Gulf, many of the aspirations built up in the 1970s were suddenly seen to be unrealistic and intense feelings of frustration followed”.

‘Western modernisation’ became discredited by economic stagnation and defeat by Israel. In Egypt, clerics equated modernity with a rejection of Islam and declared the economic and military failures of the state to be punishments for aping the West. Islamic preachers called on men to restore order and piety (i.e., female seclusion). Frustrated graduates, struggling to find white collar work, found solace in religion, whilst many ordinary people turned to the Muslim Brotherhood for social services and righteous purpose.

That’s just a brief look at a much longer and fascinating post.

What to Watch

3 Body Problem (Netflix): Great! A captivating mix of big ideas, a compelling mystery, and spectacular set-pieces like the Cultural Revolution, strange worlds, the ship cutting and more. Of course, there are some weaknesses. 3 Body Problem falters in its portrayal of genius, rendering the British scientists as too normal, overlooking the obsessiveness, ambition, and unconventionality often found in real-world geniuses. Ironically, in its effort to diversify gender and race, the series inadvertently narrows the spectrum of personality and neurodiversity. Only Ye Wenjie, traumatized by the cultural revolution, obsessed by physics and revenge, and with a messianic personality hits the right notes. Regardless, I am eager for Season 2.

Shogun (Hulu): Great meeting of cultures. Compelling plot, based on the excellent Clavell novel. I didn’t know that some of the warlords of the time (1600) had converted to Christianity. (Later banned and repressed as in Silence). Shogun avoids two traps, the Japanese have agency and so does the European. Much of it is in Japanese with subtitles.

Shogun (Hulu): Great meeting of cultures. Compelling plot, based on the excellent Clavell novel. I didn’t know that some of the warlords of the time (1600) had converted to Christianity. (Later banned and repressed as in Silence). Shogun avoids two traps, the Japanese have agency and so does the European. Much of it is in Japanese with subtitles.

Monsieur Spade: It starts with a great premise, twenty years after the events of “The Maltese Falcon,” Sam Spade has retired in a small town in southern France still riven by World War II and Algeria. Clive Owen is excellent as Spade and there are some good noir lines:

Henri Thibaut: You were in the army, Mr. Spade?

Sam Spade: No, I was a conscientious objector.

Henri Thibaut: You don’t believe in killing your fellow man?

Sam Spade: Oh, I think there’s plenty of men worth killing, as well as plenty of wars worth fighting, I’d just rather choose myself.

Yet for all the promise, I didn’t finish the series. In addition to being set in France, Monsieur Spade has a French cinema atmosphere, boring, long, vaguely pretentious. There is also a weird fascination with smoking, does it pay off with anything? I don’t know. Didn’t finish it.

My contentious Conversation with Jonathan Haidt

Here is the transcript, audio, and video. Here is the episode summary:

But might technological advances and good old human resilience allow kids to adapt more easily than he thinks?

Jonathan joined Tyler to discuss this question and more, including whether left-wingers or right-wingers make for better parents, the wisest person Jonathan has interacted with, psychological traits as a source of identitarianism, whether AI will solve the screen time problem, why school closures didn’t seem to affect the well-being of young people, whether the mood shift since 2012 is not just about social media use, the benefits of the broader internet vs. social media, the four norms to solve the biggest collective action problems with smartphone use, the feasibility of age-gating social media, and more.

It is a very different tone than most CWTs, most of all when we get to social media. Here is one excerpt:

COWEN: There are two pieces of evidence — when I look at them, they don’t seem to support your story out of sample.

HAIDT: Okay, great. Let’s have it.

COWEN: First, across countries, it’s mostly the Anglosphere and the Nordic countries, which are more or less part of the Anglosphere. Most of the world is immune to this, and smartphones for them seem fine. Why isn’t it just that a negative mood came upon the Anglosphere for reasons we mostly don’t understand, and it didn’t come upon most of the rest of the world? If we’re differentiating my hypothesis from yours, doesn’t that favor my view?

HAIDT: Well, once you look into the connections and the timing, I would say no. I think I see what you’re saying now, but I think your view would say, “Just for some reason we don’t know, things changed around 2012.” Whereas I’m going to say, “Okay, things changed around 2012 in all these countries. We see it in the mental illness rates, especially of the girls.” I’m going to say it’s not just some mood thing. It’s like (a), why is it especially the girls? (b) —

COWEN: They’re more mimetic, right?

HAIDT: Yes, that’s true.

COWEN: Girls are more mimetic in general.

HAIDT: That’s right. That’s part of it. You’re right, that’s part of it. They’re just much more open to connection. They’re more influenced. They’re more subject to contagion. That is a big part of it, you’re right. What Zach Rausch and I have found — he’s my lead researcher at the After Babel Substack. I hope people will sign up. It’s free. We’ve been putting out tons of research. Zach has really tracked down what happened internationally, and I can lay it out.

Now I know the answer. I didn’t know it two months ago. The answer is, within countries, as I said, it’s the people who are conservative and religious who are protected, and the others, the kids get washed out to sea. Psychologically, they feel their life has no meaning. They get more depressed. Zach has looked across countries, and what you find in Europe is that, overall, the kids are getting a little worse off psychologically.

But that hides the fact that in Eastern Europe, which is getting more religious, the kids are actually healthier now than they were 10 years ago, 15 years ago. Whereas in Catholic Europe, they’re a little worse, and in Protestant Europe, they’re much worse.

It doesn’t seem to me like, oh, New Zealand and Iceland were talking to each other, and the kids were sharing memes. It’s rather, everyone in the developed world, even in Eastern Europe, everyone — their kids are on phones, but the penetration, the intensity, was faster in the richest countries, the Anglos and the Scandinavians. That’s where people had the most independence and individualism, which was pretty conducive to happiness before the smartphone. But it now meant that these are the kids who get washed away when you get that rapid conversion to the phone-based childhood around 2012. What’s wrong with that explanation?

COWEN: Old Americans also seem grumpier to me. Maybe that’s cable TV, but it’s not that they’re on their phones all the time. And you know all these studies. If you try to assess what percentage of the variation in happiness of young people is caused by smartphone usage — Sabine Hossenfelder had a recent video on this — those numbers are very, very, very small. That’s another measurement that seems to discriminate in favor of my theory, exogenous mood shifts, rather than your theory. Why not?

Very interesting throughout, recommended. And do not forget that Jon’s argument is outlined in detail in his new book, titled The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness.

My Conversation with Fareed Zakaria

Here is the audio, video, and transcript. You can tell he knows what an interview is! At the same time, he understands this differs from many of his other venues and he responds with flying colors. Here is the episode summary:

Tyler sat down with Fareed to discuss what he learned from Khushwant Singh as a boy, what made his father lean towards socialism, why the Bengali intelligentsia is so left-wing, what’s stuck with him from his time at an Anglican school, what’s so special about visiting Amritsar, why he misses a more syncretic India, how his time at the Yale Political Union dissuaded him from politics, what he learned from Walter Isaacson and Sam Huntington, what put him off academia, how well some of his earlier writing as held up, why he’s become focused on classical liberal values, whether he had reservations about becoming a TV journalist, how he’s maintained a rich personal life, and more.

Here is one excerpt:

COWEN: Why couldn’t you talk Singh out of his Nehruvian socialism? He was a great liberal. He loved free speech, very broad-minded, as you know much better than I do. But he, on economics, was weak. Or no?

ZAKARIA: Oh, no, you’re entirely right. By the way, I would say the same is true of my father, with whom I had many, many such conversations. You’d find this interesting, Tyler. My father was a young Indian nationalist who — as he once put it to me — made the most important decision in his life, politically, when he was 13 or 14 years old, which was, as a young Indian Muslim, he chose Nehru’s vision of secular democracy as the foundation of a nation rather than Jinnah’s view of religious nationalism. He chose India rather than Pakistan as an Indian Muslim.

He was politically so interesting and forward-leaning, but he was a hopeless social — a sort of social democrat, but veering towards socialism. Both these guys were. Here’s why, I think. For that whole generation of people — by the way, my father got a scholarship to London University and went to study with Harold Laski, the great British socialist economist. Laski told him, “You are actually not an economist; you are a historian.” So, my father went on and got a PhD at London University in Indian history.

That whole generation of Indians who wanted independence were imbued with . . . There were two things going on. One, the only people in Britain who supported Indian independence were the Labour Party and the Fabian Socialists. All their allies were all socialists. There was a common cause and there was a symbiosis because these were your friends, these were your allies, these were the only people supporting you, the cause that mattered the most to you in your life.

The second part was, a lot of people who came out of third-world countries felt, “We are never going to catch up with the West if we just wait for the market to work its way over hundreds of years.” They looked at, in the ’30s, the Soviet Union and thought, “This is a way to accelerate modernization, industrialization.” They all were much more comfortable with the idea of something that sped up the historical process of modernization.

My own view was, that was a big mistake, though I do think there are elements of what the state was able to do that perhaps were better done in a place like South Korea than in India, but that really explains it.

My father was in Britain in ’45 as a student. As a British subject then, you got to vote in the election if you were in London, if you were in Britain. I said to him, “Who did you vote for in the 1945 election?” Remember, this is the famous election right after World War II, in which Churchill gets defeated, and he gets up the next morning and looks at the papers, and his wife says to him, “Darling, it’s a blessing in disguise.” He says, “Well, at the moment it seems very effectively disguised.”

My father voted in that election. I said to him, “You’re a huge fan of Churchill,” because I’d grown up around all the Churchill books, and my father could quote the speeches. I said, “Did you vote for Churchill?” He said, “Oh good lord, no.” I said, “Why? I thought you were a great admirer of his.” He said, “Look, on the issue that mattered most to me in life, he was an unreconstructed imperialist. A vote for Labour was a vote for Indian independence. A vote for Churchill was a vote for the continuation of the empire.” That, again, is why their friends were all socialists.

Excellent throughout. And don’t forget Fareed’s new book — discussed in the podcast — Age of Revolutions: Progress and Backlash from 1600 to the Present.

What should I ask Fareed Zakaria?

Here is Fareed’s home page, here is Wikipedia:

Fareed Rafiq Zakaria…is an Indian-American journalist, political commentator, and author. He is the host of CNN‘s Fareed Zakaria GPS and writes a weekly paid column for The Washington Post. He has been a columnist for Newsweek, editor of Newsweek International, and an editor at large of Time.

He was managing editor of Foreign Affairs at age 28, briefly a wine columnist for Slate, and much more. His new book Age of Revolutions: Progress and Backlash from 1600 to the Present is very classically liberal, and in my terms “Progress Studies”-oriented.

So what should I ask him?

Hazlett on T-Mobile/Sprint

Tom Hazlett whose op-ed on the T-Mobile Sprint merger I quoted earlier writes me:

A few thoughts on your robust MR debate: (1) Were we to observe the counterfactual over the post-merger period we would have additional evidence – no disagreement. But the counterfactuals are themselves controversial to construct, and antitrust analyses typically make just the “before/after” prediction referenced. As the case against the merger (brought by several states, but rejected by a federal court) put it: “The proposed transaction would eliminate Sprint as a competitor… This increased market concentration will result in diminished competition, higher prices, and reduced quality and innovation.”

(2) There is powerful supporting evidence about merger effects apart from the retail price data. If real, quality-adjusted rates were anticipated to drop at even a faster clip (without a merger), reversing a pre-merger pro-consumer trend, then the post-merger performance in stock prices would have benefited the three incumbents in the market. Instead, two of the three firms have seen large abnormal declines in share values.

(3) The “cozy triopoly” theory is itself upended by both the firm stock price performances and the pattern of capital investments. The “Demsetz Critique” of the Structure-Conduct-Performance paradigm showed that a positive concentration-profits correlation does not imply monopolistic behavior if the proximate cause of the excess profits is efficiency. Here, T-Mobile’s network improvements appear to be caused by its merger-based spectrum acquisitions, and these upgrades linked to its subscriber growth and capital gains. The non-merging mobile rivals have suffered highly negative returns, likely in significant part from intensified competitive challenges that forced them to make large investments in response. In 2021, Verizon and AT&T combined to pay over $75 billion for spectrum rights in an FCC auction, easily the most ever paid by two (or any number of) license bidders. Cartel formation predictably reduces rivalry; evidence of firms aggressively increasing capex to better compete for market share runs counter to the expectation.

(4) Industry analysts – who provide third-party evaluations often given great weight by antitrust authorities – support these interpretations. In Dec. 2022, e.g., sector expert Craig Moffett (MoffettNathanson) wrote: “We expect T-Mobile to continue, and indeed accelerate, their market share gains versus AT&T and Verizon, as T-Mobile’s 5G network superiority becomes increasingly evident and increasingly relevant as 5G handsets become ubiquitous. The combination of a single telecom operator having both the industry’s best network and its lowest prices is unprecedented… “

(5) A 750-word oped is not the ultimate format for such evidence. My Working Paper with Robert Crandall (formerly of Brookings, now with the Technology Policy Institute) supplies a more complete analysis – comments again welcome.

Should AM radios be mandated in cars?

No. Here is my Bloomberg column to that effect, excerpt:

Personally, I prefer to listen to XM satellite radio, a paid subscription service. It features channels that appeal to my specific tastes (in this case, if you’re asking, the Beatles, classical music and various Spanish-language programs). AM radio, which is usually advertiser-supported, tends to have more of a “least common denominator” flavor, as it must attract many listeners to pull in the ad revenue. I do not think the federal government should be using the force of law to favor cultural options that are already trying to appeal to the least common denominator.

When I bought my current car, it was capable of receiving a satellite radio signal, and I simply had to request that it be turned on. (This ease of use is one reason why I purchased the model, so the commercial considerations here are real.) There was no law requiring the satellite radio option — just as there should be none requiring an AM radio option. This symmetry of treatment meets standards of both fairness and economic efficiency.

So I’ll say it again, no AM radio should not be mandated in cars, even though Congress is thinking of doing this on a bipartisan basis.

My Conversation with the excellent Ami Vitale

Here is the audio, visual, and transcript. Here is the episode summary:

Ami Vitale is a renowned National Geographic photographer and documentarian with a deep commitment to wildlife conservation and environmental education. Her work, spanning over a hundred countries, includes spending a decade as a conflict photographer in places like Kosovo, Gaza, and Kashmir.

She joined Tyler to discuss why we should stay scary to pandas, whether we should bring back extinct species, the success of Kenyan wildlife management, the mental cost of a decade photographing war, what she thinks of the transition from film to digital, the ethical issues raised by Afghan Girl, the future of National Geographic, the heuristic guiding of where she’ll travel next, what she looks for in a young photographer, her next project, and more.

Here is one excerpt:

COWEN: As you probably know, there’s a long-standing and recurring set of debates between animal welfare advocates and environmentalists. The animal welfare advocates typically have less sympathy for the predators because they, in turn, kill other animals. The environmentalists are more likely to think we should, in some way, leave nature alone as much as possible. Where do you stand on that debate?

VITALE: It depends. It’s hard to make a general sweeping statement on this because in some cases, I think that we do have to get involved. Also, the fact is, it’s humans in most cases who have really impacted the environment, and we do need to get engaged and work to restore that balance. I really fall on both sides of this. I will say, I do think that is, in some cases, what differentiates us because, as human beings, we have to kill to survive. Maybe that is where this — I feel like every story I work on has a different answer. Really, I don’t know. It depends what the situation is. Should we bring animals back to landscapes where they have not existed for millions of years? I fall in the line of no. Maybe I’m taking this in a totally different direction, but it’s really complicated, and there’s not one easy answer.

And:

COWEN: As you know, there are now social networks everywhere, for quite a while. Images everywhere, even before Midjourney. There are so many images that people are looking at. How does that change how you compose or think about photos?

VITALE: Well, it doesn’t at all. My job is to tell stories with images, and not just with images. My job as a storyteller — that has not changed. Nothing has changed in the sense of, we need more great storytellers, visual storytellers. With all of those social media, I think people are bored with just beautiful images. Or sometimes it feels like advertising, and it doesn’t captivate me.

I look for a story and image, and I am just going to continue doing what I do because I think people are hungry for it. They want to know who is really going deep on stories and who they can trust. I think that that has never gone away, and it will never go away.

I am very happy to have guests who do things that not everyone else’s guests do.

New data on media bias

In this study, we propose a novel approach to detect supply-side media bias, independent of external factors like ownership or editors’ ideological leanings. Analyzing over 100,000 articles from The New York Times (NYT) and The Wall Street Journal (WSJ), complemented by data from 22 million tweets, we assess the factors influencing article duration on their digital homepages. By flexibly controlling for demand-side preferences, we attribute extended homepage presence of ideologically slanted articles to supply-side biases. Utilizing a machine learning model, we assign “pro-Democrat” scores to articles, revealing that both tweets count and ideological orientation significantly impact homepage longevity. Our findings show that liberal articles tend to remain longer on the NYT homepage, while conservative ones persist on the WSJ. Further analysis into articles’ transition to print and podcasts suggests that increased competition may reduce media bias, indicating a potential direction for future theoretical exploration.

That is from a recent paper by Tin Cheuk Leung and Koleman Strumpf.

My Conversation with Rebecca F. Kuang

Here is the audio, video, and transcript, here is the episode summary:

Rebecca F. Kuang just might change the way you think about fantasy and science fiction. Known for her best-selling books Babel and The Poppy War trilogy, Kuang combines a unique blend of historical richness and imaginative storytelling. At just 27, she’s already published five novels, and her compulsion to write has not abated even as she’s pursued advanced degrees at Oxford, Cambridge, and now Yale. Her latest book, Yellowface, was one of Tyler’s favorites in 2023.

She sat down with Tyler to discuss Chinese science-fiction, which work of fantasy she hopes will still be read in fifty years, which novels use footnotes well, how she’d change book publishing, what she enjoys about book tours, what to make of which Chinese fiction is read in the West, the differences between the three volumes of The Three Body Problem, what surprised her on her recent Taiwan trip, why novels are rarely co-authored, how debate influences her writing, how she’ll balance writing fiction with her academic pursuits, where she’ll travel next, and more.

Here is one excerpt:

COWEN: Why do you think that British imperialism worked so much better in Singapore and Hong Kong than most of the rest of the world?

KUANG: What do you mean by work so much better?

COWEN: Singapore today, per capita — it’s a richer nation than the United States. It’s hard to think, “I’d rather go back and redo that whole history.” If you’re a Singaporean today, I think most of them would say, “We’ll take what we got. It was far from perfect along the way, but it worked out very well for us.” People in Sierra Leone would not say the same thing, right?

Hong Kong did much better under Britain than it had done under China. Now that it’s back in the hands of China, it seems to be doing worse again, so it seems Hong Kong was better off under imperialism.

KUANG: It’s true that there is a lot of contemporary nostalgia for the colonial era, and that would take hours and hours to unpack. I guess I would say two things. The first is that I am very hesitant to make arguments about a historical counterfactual such as, “Oh, if it were not for the British Empire, would Singapore have the economy it does today?” Or “would Hong Kong have the culture it does today?” Because we don’t really know.

Also, I think these broad comparisons of colonial history are very hard to do, as well, because the methods of extraction and the pervasiveness and techniques of colonial rule were also different from place to place. It feels like a useless comparison to say, “Oh, why has Hong Kong prospered under British rule while India hasn’t?” Et cetera.

COWEN: It seems, if anywhere we know, it’s Hong Kong. You can look at Guangzhou — it’s a fairly close comparator. Until very recently, Hong Kong was much, much richer than Guangzhou. Without the British, it would be reasonable to assume living standards in Hong Kong would’ve been about those of the rest of Southern China, right? It would be weird to think it would be some extreme outlier. None others of those happened in the rest of China. Isn’t that close to a natural experiment? Not a controlled experiment, but a pretty clear comparison?

KUANG: Maybe. Again, I’m not a historian, so I don’t have a lot to say about this. I just think it’s pretty tricky to argue that places prospered solely due to British presence when, without the British, there are lots of alternate ways things could have gone, and we just don’t know.

Interesting throughout.

Matt Yglesias on the media

A point I tried to make on our Politix episode with Will Stancil is that progressive-minded people — and particularly progressive-minded media figures — have a certain ideological investment in the promotion of bad vibes.

Younger left-wing people are notably more depressed than politically conservative ones, which may be partially selection effect, but I think is driven by the fact that so much progressive messaging about the world is marked by negativity and doomerism. I read a cool story last week out of the Bay Area about how BART brought engineering work for new rolling stock in-house, which wound up delivering the trains under budget and ahead of schedule. That’s an upbeat, positive news story that’s also straightforwardly left-wing in its implications. But that’s not the kind of narrative that gets traction in progressive media spaces, which are dominated by pronouncements about how we live in a late capitalist dystopian hellscape.

…it’s considered both un-progressive and un-journalistic to talk about good things rather than to expose problems.

Conservatives find it annoying that American journalists are so left-wing. But in practice, this generates a much more complicated partisan landscape than you might think. The conservative audience is alienated by the values of mainstream journalism and spends a lot of time consuming propaganda news that is optimized for partisan purposes. The progressive audience finds mainstream journalism congenial enough that it’s hard to compete with, and yet, mainstream journalism produces a steady stream of negativity and ultra-specific focus on the idiosyncratic problems of young urban professionals.

That is all from Matt’s (paid) Substack, worth subscribing to.

What should I ask Jonathan Haidt?

Yes, I will be doing another Conversation with him. Here is my previous Conversation with him, almost eight years ago. As many of you will know, Jonathan has a new book coming out, namely

2023 CWT retrospective episode

Here is the link, here is the episode summary:

On this special year-in-review episode, Tyler and producer Jeff Holmes look back on the past year in the show and more, including the most popular and underrated episodes, the origins of the show as an occasional event series, the most difficult guests to prep for, the story behind EconGOAT.AI, Tyler’s favorite podcast appearance of the year, and his evolving LLM-powered production function. They also answer listener questions and conclude with an assessment of Tyler’s top pop culture recommendations from 2013 across movies, music, and books.

And one excerpt:

COWEN: That’s a unique experience. You have a chance to do Chomsky. Maybe you don’t even want to do it, but you feel, “If I don’t do it, I’ll regret not having done it.” Just like we didn’t get to chat with Charlie Munger in time, though he’s far more, I would say, closer to truth than Chomsky is.

I thought half of Chomsky was quite good, and the other half was beyond terrible, but that’s okay. People, I think, wanted to gawk at it in some manner. They had this picture — what’s it like, Tyler talking with Chomsky? Then they get to see it and maybe recoil, but that’s what they came for, like a horror movie.

HOLMES: The engagement on the Chomsky episode was very good. Some people on MR were saying, “I turned it off. I couldn’t listen to it.” But actually, most people listened to it. It did, actually, probably better than average in terms of engagement, in terms of how much of the episode, on average, people listen to.

COWEN: How can you turn it off? What does that say about you? Were you surprised? You thought that Chomsky had become George Stigler or something? No.

Fun and interesting throughout. If you are wondering, the most popular episode of the year, by far, was with Paul Graham.

Censorship of U.S. Movies in China

We introduce a structural econometric model to estimate the extent to which the Chinese government bans U.S. movies. According to our estimates, if a movie has characteristics similar to the median movie in our sample, then the probability is approximately 0.91 that the Chinese government will ban it. During our sample period, 1994-2019, U.S. movies comprised about 28 percent of the Chinese market and sales were about $22.6 billion. However, according to our estimates, if the Chinese government had not banned any U.S. movies, then the latter numbers would have risen to 68 percent and $45.1 billion.

As for what gets banned:

…, two factors that have very high statistical significance are: (i) whether the movie contains occult content, and (ii) whether the movie

receives an R rating from the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA). The factors also have very high substantive significance. For instance, suppose two movies, A and B, are identical except that movie A contains occult content, while B does not. Suppose movie B’s probability of being banned is 50%. Then, according to our results, the occult content in movie A causes its probability of being banned to rise to 67%. A similar thought experiment implies that, if a movie has an R rating, then this raises its probability of being banned from 50% to 70%.Three other factors seem to be important but come just short of reaching statistical significance. These are whether the movie contains themes related to (i) anti-communism, (ii) individualism, or (iii) Tibet. A fourth factor is similar. This is whether the actor Richard Gere

appears in the movie.

That is a new paper by XUHAO PAN, Tim Groseclose, and yours truly, forthcoming in the Journal of Cultural Economics.

AI-generated stories and anchors

It’s so over for journalists lmfao

Learn to code chumps https://t.co/ibDoX3O9Ny

— Journalists Posting Their Ls (@JournosPostLs) December 13, 2023

p.s. Learning to code won’t do it. Become a gardener!