Category: Science

Understanding and Addressing Temperature Impacts on Mortality

Here are some important results:

A large literature documents how ambient temperature affects human mortality. Using decades of detailed data from 30 countries, we revisit and synthesize key findings from this literature. We confirm that ambient temperature is among the largest external threats to human health, and is responsible for a remarkable 5-12% of total deaths across countries in our sample, or hundreds of thousands of deaths per year in both the U.S. and EU. In all contexts we consider, cold kills more than heat, though the temperature of minimum risk rises with age, making younger individuals more vulnerable to heat and older individuals more vulnerable to cold. We find evidence for adaptation to the local climate, with hotter places experiencing somewhat lower risk at higher temperatures, but still more overall mortality from heat due to more frequent exposure. Within countries, higher income is not associated with uniformly lower vulnerability to ambient temperature, and the overall burden of mortality from ambient temperature is not falling over time. Finally, we systematically summarize the limited set of studies that rigorously evaluate interventions that can reduce the impact of heat and cold on health. We find that many proposed and implemented policy interventions lack empirical support and do not target temperature exposures that generate the highest health burden, and that some of the most beneficial interventions for reducing the health impacts of cold or heat have little explicit to do with climate.

Those are from a recent paper by Marshall Burke, et.al.

We Turned the Light On—and the AI Looked Back

Jack Clark, Co-founder of Anthropic, has written a remarkable essay about his fears and hopes. It’s not the usual kind of thing one reads from a tech leader:

I remember being a child and after the lights turned out I would look around my bedroom and I would see shapes in the darkness and I would become afraid – afraid these shapes were creatures I did not understand that wanted to do me harm. And so I’d turn my light on. And when I turned the light on I would be relieved because the creatures turned out to be a pile of clothes on a chair, or a bookshelf, or a lampshade.

Now, in the year of 2025, we are the child from that story and the room is our planet. But when we turn the light on we find ourselves gazing upon true creatures, in the form of the powerful and somewhat unpredictable AI systems of today and those that are to come. And there are many people who desperately want to believe that these creatures are nothing but a pile of clothes on a chair, or a bookshelf, or a lampshade. And they want to get us to turn the light off and go back to sleep.

…We are growing extremely powerful systems that we do not fully understand. Each time we grow a larger system, we run tests on it. The tests show the system is much more capable at things which are economically useful. And the bigger and more complicated you make these systems, the more they seem to display awareness that they are things.

It is as if you are making hammers in a hammer factory and one day the hammer that comes off the line says, “I am a hammer, how interesting!” This is very unusual!

…I am also deeply afraid. It would be extraordinarily arrogant to think working with a technology like this would be easy or simple.

My own experience is that as these AI systems get smarter and smarter, they develop more and more complicated goals. When these goals aren’t absolutely aligned with both our preferences and the right context, the AI systems will behave strangely.

…we are not yet at “self-improving AI”, but we are at the stage of “AI that improves bits of the next AI, with increasing autonomy and agency”. And a couple of years ago we were at “AI that marginally speeds up coders”, and a couple of years before that we were at “AI is useless for AI development”. Where will we be one or two years from now?

And let me remind us all that the system which is now beginning to design its successor is also increasingly self-aware and therefore will surely eventually be prone to thinking, independently of us, about how it might want to be designed.

…In closing, I should state clearly that I love the world and I love humanity. I feel a lot of responsibility for the role of myself and my company here. And though I am a little frightened, I experience joy and optimism at the attention of so many people to this problem, and the earnestness with which I believe we will work together to get to a solution. I believe we have turned the light on and we can demand it be kept on, and that we have the courage to see things as they are.

Clark is clear that we are growing intelligent systems that are more complex than we can understand. Moreover, these systems are becoming self-aware–that is a fact, even if you think they are not sentient (but beware hubris on the latter question).

Nobel Prize in economics goes to Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt and Joel Mokyr

Excellent choices. Here is the press release with links to longer discussions of their works.

This is a prize for economic growth, and for the ideas of creative destruction. Those are some of the most important ideas in economics, so I could not be happier with this pick. Joel Mokyr in particular has been a long-time associate of GMU and Mercatus, so I would like to congratulate him in particular.

Aghion is at INSEAD in France, Howitt at Brown, and Mokyr at Northwestern. It is also nice to see some people outside of “the usual schools” winning the prize. Aghion and Howitt, of course, worked together to produce a model of creative destruction and economic growth. Here are their key papers together.

Joel Mokyr is an economic historian, and best known for his pioneering work in explaining the Industrial Revolution in England. Here are his best-known works. Read The Lever of Riches and The Gifts of Athena and A Culture of Growth. I have benefited most from The Enlightened Economy: An Economic History of Britain 1700-1850. He has a new book coming out in November, with Tabellini and Greif. It is correct to consider him as an “Enlightenment thinker.” Brian Albrecht has a good thread on this.

Below you can find individual posts on Aghion, Howitt, and also Mokyr. Here is Alex’s post on the prize.

Science Policy Insider

That is a new Substack by Jim Olds, here is the introduction:

How science funding really works—from someone who ran the machinery at NSF and NIH.

I’m Jim Olds, former head of the National Science Foundation’s $750M Biological Sciences Directorate (2014-2018), NSF lead for President Obama’s BRAIN Initiative, and co-chair of the White House Life Sciences Subcommittee.

Over three decades in Washington D.C., I’ve seen how science policy actually works—not from the sidelines, but from inside the decision-making rooms. I’ve reviewed thousands of grants, managed billion-dollar budgets, and worked with everyone from Nobel laureates to members of Congress.

What you’ll get here:

– The real story of how funding decisions get made

– Insider analysis of science policy debates and initiatives

– Practical insights on what makes big science succeed or fail

– Honest perspectives on the challenges facing research funding

This isn’t speculation or critique from the outside. It’s the view from someone who was in the room where it happened.

This newsletter is free

What should I ask Blake Scholl?

The Boom guy doing supersonic flight! I will be doing a podcast with him at the forthcoming Roots of Progress Institute event. He already has told “his story” on the supersonic side a number of times, so what else of interest should we cover? For background, here is Blake on Wikipedia.

New archaeology tranche for Emergent Ventures

Just apply at the normal site. Here is a description of what we are up to and what we are looking for:

- We are giving archaeology-specific EV grants

- Emphasis on projects enabled by tech (AI/CV, lidar, synthetic aperture radar and hyperspectral imagery, open source data, etc)

- Flexible on cost or duration of projects

- All circumstances encouraged (grad student funding a project she’s working on, swe wanting to take a few months off to work on something, high school student side project, etc)

- Ideas below are by no means comprehensive or the edges of the search area – just starting points for exploration for people interested in the field that don’t have a specific idea in mind yet

Examples of ideas:

- Transcribing, digitizing, and open-sourcing cuneiform tablets and other writing

- OCR and cataloguing old scripts (Maya glyphs, Sanskrit, etc)

- Scanning coastlines along old civilizations for submerged sites

- Improved ground penetrating radar

- Improving AI for translation of old and obscure languages, and mass translation

- Deciphering Linear A. Are existing proposed decipherments such as this one plausible? https://x.com/natfriedman/status/1756414276779253872?s=46

- Reading lumped Maya codices (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maya_codices#Other_Maya_codices)

- Reading Chinese bamboo slips and silk manuscripts (https://x.com/jordanschnyc/status/1920181694327362007)

- Using AI to check vast amounts of land for sites (good example: https://x.com/byornoste/status/1927434033685827726)

- Lidar scanning forests to find structures beneath the canopy (https://x.com/mehran__jalali/status/1934693744630223228)

- Using SAR/hyperspectral scans for finding sites

For these notes I thank Mehran Jalali, a former EV winner in this area, who also will serve as one of the referees. When you apply, just indicate that your request is for archaeology. Soon this will be a formal category on the application itself, if somehow you are already ready to apply tomorrow a.m., just use the word in your project description.

We thank Yonatan Ben Shimon for his generous support of this tranche.

AI Scientists in the Lab

Today, we introduce Periodic Labs. Our goal is to create an AI scientist.

Science works by conjecturing how the world might be, running experiments, and learning from the results.

Intelligence is necessary, but not sufficient. New knowledge is created when ideas are found to be consistent with reality. And so, at Periodic, we are building AI scientists and the autonomous laboratories for them to operate.

…Autonomous labs are central to our strategy. They provide huge amounts of high-quality data (each experiment can produce GBs of data!) that exists nowhere else. They generate valuable negative results which are seldom published. But most importantly, they give our AI scientists the tools to act.

…One of our goals is to discover superconductors that work at higher temperatures than today’s materials. Significant advances could help us create next-generation transportation and build power grids with minimal losses. But this is just one example — if we can automate materials design, we have the potential to accelerate Moore’s Law, space travel, and nuclear fusion.

Our founding team co-created ChatGPT, DeepMind’s GNoME, OpenAI’s Operator (now Agent), the neural attention mechanism, MatterGen; have scaled autonomous physics labs; and have contributed to important materials discoveries of the last decade. We’ve come together to scale up and reimagine how science is done.

The AI’s can work 24 hours a day, 365 days a year and with labs under their control the feedback will be quick. In nine hours, AlphaZero taught itself chess and then trounced the then world champion Stockfish 8, (ELO around 3378 compared to Magnus Carlsen’s high of 2882). That was in 2017. In general, experiments are more open-ended than chess but not necessarily in every domain. Moreover context windows and capabilities have grown tremendously since 2017.

In other AI news, AI can be used to generate dangerous proteins like ricin and current safeguards are not very effective:

Microsoft bioengineer Bruce Wittmann normally uses artificial intelligence (AI) to design proteins that could help fight disease or grow food. But last year, he used AI tools like a would-be bioterrorist: creating digital blueprints for proteins that could mimic deadly poisons and toxins such as ricin, botulinum, and Shiga.

Wittmann and his Microsoft colleagues wanted to know what would happen if they ordered the DNA sequences that code for these proteins from companies that synthesize nucleic acids. Borrowing a military term, the researchers called it a “red team” exercise, looking for weaknesses in biosecurity practices in the protein engineering pipeline.

The effort grew into a collaboration with many biosecurity experts, and according to their new paper, published today in Science, one key guardrail failed. DNA vendors typically use screening software to flag sequences that might be used to cause harm. But the researchers report that this software failed to catch many of their AI-designed genes—one tool missed more than 75% of the potential toxins.

Solve for the equilibrium?

Good job people, congratulations…

“Sonnet 4.5 does complete replication checks of an econpaper.”

That is Kevin Bryan, here is more from Ethan Mollick.

What should I ask Alison Gopnik?

Yes, I will be doing a Conversation with her. Here is Wikipedia:

Alison Gopnik (born June 16, 1955) is an American professor of psychology and affiliate professor of philosophy at the University of California, Berkeley. She is known for her work in the areas of cognitive and language development, specializing in the effect of language on thought, the development of a theory of mind, and causal learning. Her writing on psychology and cognitive science has appeared in Science, Scientific American, The Times Literary Supplement, The New York Review of Books, The New York Times, New Scientist, Slate and others. Her body of work also includes four books and over 100 journal articles…

Gopnik has carried out extensive work in applying Bayesian networks to human learning and has published and presented numerous papers on the topic…Gopnik was one of the first psychologists to note that the mathematical models also resemble how children learn.

Gopnik is known for advocating the “theory theory” which postulates that the same mechanisms used by scientists to develop scientific theories are used by children to develop causal models of their environment.

Here is her home page. So what should I ask her?

H1-B visa fees and the academic job market

Assume the courts do not strike this down (perhaps they will?).

Will foreigners still be hired at the entry level with an extra 100k surcharge? I would think not,as university budgets are tight these days. I presume there is some way to turn them down legally, without courting discrimination lawsuits?

What if you ask them to accept a lower starting wage? A different deal in some other manner, such as no summer money or a higher teaching load? Is that legal? Will schools have the stomach to even try? I would guess not. Is there a way to amortize the 100k over five or six years? What if the new hire leaves the institution in year three of the deal?

In economics at least, a pretty high percentage of the graduate students at top institutions do not have green cards or citizenships.

So how exactly is this going to work? There are not so many jobs in Europe, not enough to absorb those students even if they wish to work there. Will many drop out right now? And if the flow of graduate students is not replenished, given that entry into the US job market is now tougher, how many graduate programs will close up?

Will Chinese universities suddenly hire a lot more quality talent?

Here is some related discussion on Twitter.

As they say, solve for the equilibrium…

AI and weather tracking as a very positive intervention

India’s monsoon season was unusual this year, but many farmers there had new AI weather-forecasting tools to help them ride out the storms.

Google’s open-source artificial intelligence model NeuralGCM and the European Center for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts’s AI systems are making sophisticated and granular forecasting data available to even the smallest farms in poor areas. Thanks to the open-source AI, and decades of rainfall data, the Indian government sent out forecasts to 38 million farmers to warn them about looming monsoons.

The initiative to help farmers adapt is the latest example of how companies are expanding their weather-tracking capabilities amid mounting concerns about extreme weather and climate change.

The effort is part of a growing “democratization of weather forecasting,” said Pedram Hassanzadeh, a researcher at the University of Chicago who focuses on machine learning and extreme weather. Researchers from the university partnered with the Indian government to gather and send out the monsoon predictions.

“Up until very recently, to run a weather model, you needed a 100 million-dollar supercomputer,” said Olivia Graham, a product manager at Google Research. But now, farmers in India can make better-informed agricultural decisions quickly, she said.

These projects seem to have very high benefit to cost ratios. Here is one relevant RCT, here is another. Here is more from the WSJ, via Michael Kremer. Here is a useful and informative press release.

New print edition of Works in Progress

Amazing, here is the site: “The print edition contains everything you can get online, plus a lot more: print-exclusive columns, beautiful art and design, letters from our readers and editors, and visual explainers of technology.”

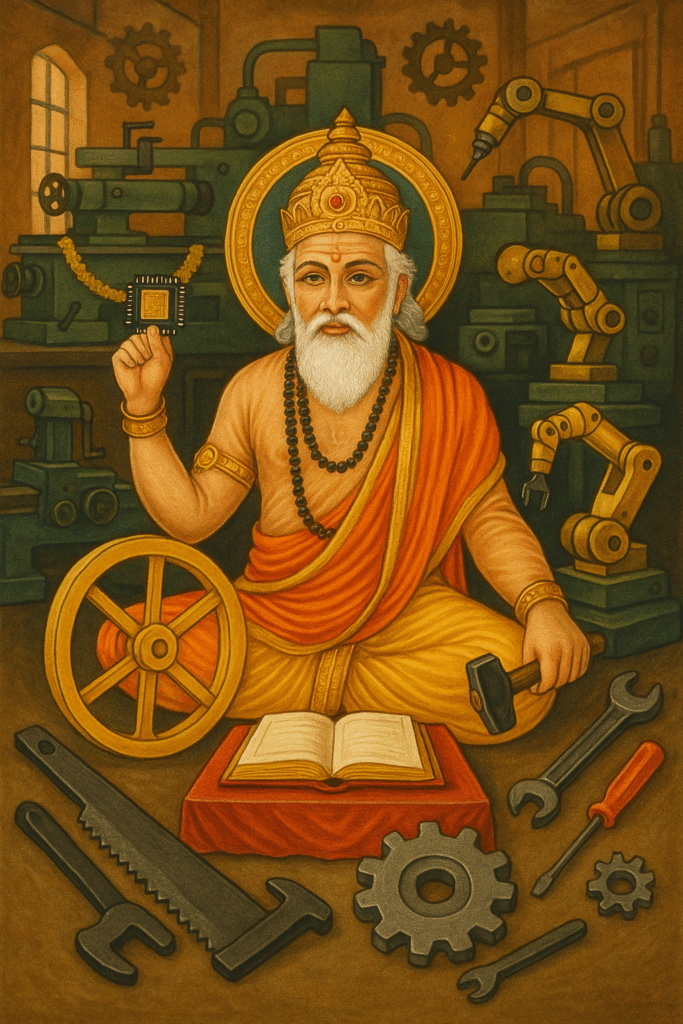

Celebrate Vishvakarma: A Holiday for Machines, Robots, and AI

Most holidays celebrate people, gods or military victories. Today is India’s Vishvakarma Puja, a celebration of machines. In India on this day, workers clean and honor their equipment and engineers pay tribute to Vishvakarma, the god of architecture, engineering and manufacturing.

Most holidays celebrate people, gods or military victories. Today is India’s Vishvakarma Puja, a celebration of machines. In India on this day, workers clean and honor their equipment and engineers pay tribute to Vishvakarma, the god of architecture, engineering and manufacturing.

Call it a celebration of Solow and a reminder that capital, not just labor, drives growth.

Capital today isn’t just looms and tractors—it’s robots, software, and AI. These are the new force multipliers, the machines that extend not only our muscles but our minds. To celebrate Vishvakarma is to celebrate tools, tool makers and the capital that makes us productive.

We have Labor Day for workers and Earth Day for nature. Viskvakarma Day is for the machines. So today don’t thank Mother Earth, thank the machines, reflect on their power and productivity and be grateful for all that they make possible. Capital is the true source of abundance.

Vishvakarma Day should be our national holiday for abundance and progress.

Hat tip: Nimai Mehta.

AI Agents for Economic Research

The objective of this paper is to demystify AI agents – autonomous LLM-based systems that plan, use tools, and execute multi-step research tasks – and to provide hands-on instructions for economists to build their own, even if they do not have programming expertise. As AI has evolved from simple chatbots to reasoning models and now to autonomous agents, the main focus of this paper is to make these powerful tools accessible to all researchers. Through working examples and step-by-step code, it shows how economists can create agents that autonomously conduct literature reviews across myriads of sources, write and debug econometric code, fetch and analyze economic data, and coordinate complex research workflows. The paper demonstrates that by “vibe coding” (programming through natural language) and building on modern agentic frameworks like LangGraph, any economist can build sophisticated research assistants and other autonomous tools in minutes. By providing complete, working implementations alongside conceptual frameworks, this guide demonstrates how to employ AI agents in every stage of the research process, from initial investigation to final analysis.

The Simple Mathematics of Chinese Innovation

The NYTimes has a good data-driven piece on How China Went From Clean Energy Copycat to Global Innovator, the upshot of which is that the old view of China as simply copying (“stealing” in some eyes) no longer describes reality. In some fields, including solar, batteries and hydrogen, China is now the leading innovator as measured by high-quality patents and scientific citations.

None of this should surprise anyone. China employs roughly 2.6 million full-time equivalent (FTE) researchers versus about 1.7 million in the United States. On a per-capita basis the U.S. is ahead—about 4,500 researchers per million people versus China’s 1,700—but population scale tips the balance. China simply has more researchers in absolute terms. If you frame it in terms of rare cognitive talent, as in my post on The Extreme Shortage of High IQ Workers—the arithmetic is even more striking: 1-in-1,000 workers (≈IQ 145) ~170,000 in the U.S. labor force and ~770,000 in China. Scale matters.

In the 20th century the world’s most populous countries were poor but that was neither the case historically nor will it be true in the 21st century. The standard of living in China remains well below that in the United States and China may never catch U.S. GDP per capita, but quantity is a quality of its own. More people means more ideas.

To be clear, the rise of China and India as scientific superpowers is not per se a threat. Whiners complain about US pharmaceutical R&D “subsidizing” the world. Well, Chinese pharmaceutical innovation is now saving American lives. Terrific. Ideas don’t stop at borders, and their spread raises living standards everywhere. It would be wonderful if an American cured cancer. It would be 99% as wonderful if a Chinese scientist did. What matters is that when more scientists attack the problem, the odds of a cure rise so we should look favorably on a world with more scientists. That is progress.

The danger is not China’s rise but America’s mindset. Treat science as zero-sum and every Chinese patent looks like a loss. But ideas are nonrival: a Chinese breakthrough doesn’t make Americans poorer, it makes the world richer. A multi-polar scientific world means faster growth, greater wealth, and accelerating technology—even if America wins a smaller share of the Nobels.