Category: Science

New data on tenure

Tenure is a defining feature of the US academic system with significant implications for research productivity and creative search. Yet the impact of tenure on faculty research trajectories remains poorly understood. We analyze the careers of 12,000 US faculty across 15 disciplines to reveal key patterns, pre- and post-tenure. Publication rates rise sharply during the tenure-track, peaking just before tenure. However, post-tenure trajectories diverge: Researchers in lab-based fields sustain high output, while those in non-lab-based fields typically exhibit a decline. After tenure, faculty produce more novel works, though fewer highly cited papers. These findings highlight tenure’s pivotal role in shaping scientific careers, offering insights into the interplay between academic incentives, creativity, and impact while informing debates about the academic system.

Here is the paper. That is by Giorgio Tripodi, Ziang Zheng, Yifan Qian, and Dashun Wang, via the excellent Kevin Lewis.

Genius, Rejected: Emergent Ventures Versus the System

Quanta Magazine has a good piece on a 17-year-old student who disproved a long-standing conjecture in harmonic analysis:

Yet a paper posted on February 10(opens a new tab) left the math world by turns stunned, delighted and ready to welcome a bold new talent into its midst. Its author was Hannah Cairo(opens a new tab), just 17 at the time. She had solved a 40-year-old mystery about how functions behave, called the Mizohata-Takeuchi conjecture.

“We were all shocked, absolutely. I don’t remember ever seeing anything like that,” said Itamar Oliveira (opens aof the University of Birmingham, who has spent the past two years trying to prove that the conjecture was true. In her paper, Cairo showed that it’s false. The result defies mathematicians’ usual intuitions about what functions can and cannot do.

…The proof, and its unlikely author, have energized the math community since Cairo posted it in February. “I was absolutely, ‘Wow.’ This has been my favorite problem for nigh on 40 years, and I was completely blown away,” Carbery said.

Here is the abstract to the paper:

I can’t speak to the mathematics but this is Quanta Magazine not People Magazine and Cairo is not coming out of nowhere. As the article discusses, she has been taking graduate classes in mathematics at Berkeley from people like Ruixiang Zhang. So what is the problem?

I was enraged by the following:

After completing the proof, she decided to apply straight to graduate school, skipping college (and a high school diploma) altogether. As she saw it, she was already living the life of a graduate student. Cairo applied to 10 graduate programs. Six rejected her because she didn’t have a college degree. Two admitted her, but then higher-ups in those universities’ administrations overrode those decisions.

Only the University of Maryland and Johns Hopkins University were willing to welcome her straight into a doctoral program.

Kudos to UMD and JHU! But what is going on at those other universities?!! Their sole mission is to identify and nurture talent. They have armies of admissions staff and tout their “holistic” approach to recognizing creativity and intellectual promise even when it follows an unconventional path. Yet they can’t make room for a genius who has been vetted by some of the top mathematicians in the world? This is institutional failure.

We saw similar failures during COVID: researchers at Yale’s School of Public Health, working on new tests, couldn’t get funding from their own billion-dollar institution and would have stalled without Tyler’s Fast Grants. But the problem isn’t just speed. Emergent Ventures isn’t about speed but about discovering talent. If you wonder why EV has been so successful look to Tyler and people like Shruti Rajagopalan and to the noble funders but look also to the fact that their competitors are so bureaucratic that they can’t recognize talent even when it is thrust upon them.

It’s a very good thing EV exists. But you know your city is broken when you need Batman to fight crime. EV will have truly succeeded when the rest of the system is inspired into raising its game.

Berthold and Emanuel Lasker

A fun rabbit hole! Berthold was world chess champion Emanuel Lasker’s older brother, and also his first wife was Elsa Lasker-Schüler, the avant-garde German Jewish poet and playwright.

In the 1880s (!) he developed what later was called “Fischer Random” chess, Chess960, or now “freestyle chess,” as Magnus Carlsen has dubbed it. The opening arrangement of the pieces is randomized on the back rank, to make the game more interesting and also avoid the risks of excessive opening preparation and too many draws. He was prescient in this regard, though at the time chess was very far from having exhausted the possiblities for interesting openings that were not played out.

For a while he was one of the top ten chess players in the world, and he served as mentor to his brother Emanuel. Emanuel, in due time, became world chess champion, was an avid and excellent bridge and go player, invented a variant of checkers called “Lasca,” made significant contributions to mathematics, and was known for his work in Kantian philosophy.

Of all world chess champions, he is perhaps the one whose peers failed to give him much of a serious challenge. Until of course Capablanca beat him in 1921.

Design Your Own Rug!

For my wedding anniversary, I designed and had hand-woven in Afghanistan a rug for my microbiologist wife. The rug mixes traditional Afghanistan designs with some scientific elements including Bunsen burners, test tubes, bacterial petri dishes and other elements.

I started with several AI designs, such as that shown below, to give the weavers an idea of what I was looking for. Some of the AI elements were muddled and very complex and so we developed a blueprint over a few iterations. The blueprint was very accurate to the actual rug.

I am very pleased with the final product. The wool is of high quality, deep and luxurious, and the design is exactly what I intended. My wife loves the rug and will hang it at her office. The price was very reasonable, under $1000. I also like that I employed weavers in a small village in Northern Afghanistan. The whole process took about 6 months.

You can develop your own custom rug from Afghanu Rugs. Tell them Alex sent you. Of course, they also have many beautiful traditional designs. You can even order my design should you so desire!

That was then, this is now, AI edition

COWEN: They can now do Math Olympiad problems. There’s one forecast by someone working on this that, within a year, they’ll win Math Olympiads. It could be wrong, but when you say that it’s only a year away, I would take that pretty seriously.

That was from my Nate Silver CWT taped on July 22, 2024. We just taped a new episode today…

Noam Brown reports

Today, we at @OpenAI achieved a milestone that many considered years away: gold medal-level performance on the 2025 IMO with a general reasoning LLM—under the same time limits as humans, without tools.

Here is the link, here is some commentary. And Nat McAleese. And the prediction market. Emad: “Two years ago, who would have said an IMO gold medal & topping benchmarks isn’t AGI?” And it is good at other things too.

And from Alexander Wei: “Btw, we are releasing GPT-5 soon, and we’re excited for you to try it. But just to be clear: the IMO gold LLM is an experimental research model. We don’t plan to release anything with this level of math capability for several months.”

David Brooks on the AI race

When it comes to confidence, some nations have it and some don’t. Some nations once had it but then lost it. Last week on his blog, “Marginal Revolution,” Alex Tabarrok, a George Mason economist, asked us to compare America’s behavior during Cold War I (against the Soviet Union) with America’s behavior during Cold War II (against China). I look at that difference and I see a stark contrast — between a nation back in the 1950s that possessed an assumed self-confidence versus a nation today that is even more powerful but has had its easy self-confidence stripped away.

There is much more at the NYT link.

The Sputnik vs. Deep Seek Moment: The Answers

In The Sputnik vs. DeepSeek Moment I pointed out that the US response to Sputnik was fierce competition. Following Sputnik, we increased funding for education, especially math, science and foreign languages, organizations like ARPA were spun up, federal funding for R&D was increased, immigration rules were loosened, foreign talent was attracted and tariff barriers continued to fall. In contrast, the response to what I called the “DeepSeek” moment has been nearly the opposite. Why did Sputnik spark investment while DeepSeek sparks retrenchment? I examine four explanations from the comments and argue that the rise of zero-sum thinking best fits the data.

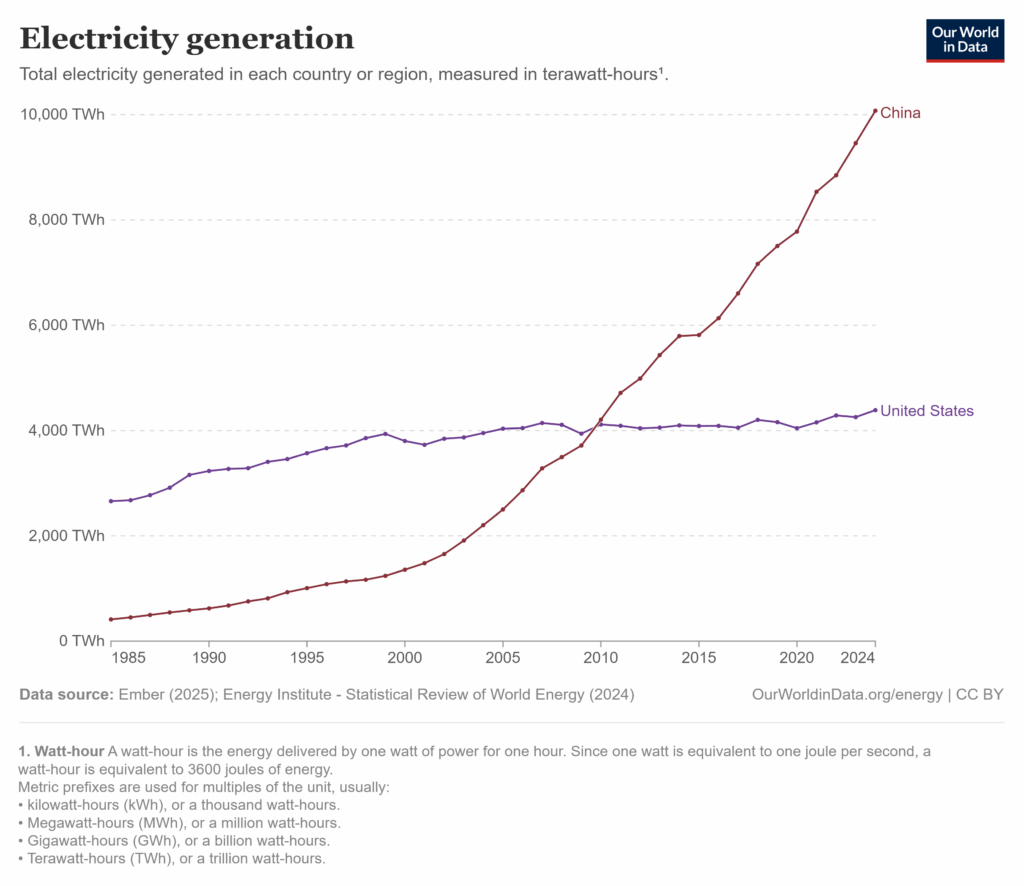

Several comments fixated on DeepSeek itself, dismissing it as neither impressive nor threatening. Perhaps but DeepSeek was merely a symbol for China’s broader rise: the world’s largest exporter, manufacturer, electricity producer, and military by headcount. These critiques missed the point.

Some commenters argued that Sputnik provoked a strong response because it was seen as an existential threat, while DeepSeek—and by extension China—is not. I certainly hope China’s rise isn’t existential, and I’m encouraged that China lacks the Soviet Union’s revolutionary zeal. As I’ve said, a richer China offers benefits to the United States.

But many influential voices do view China as a very serious, even existential, threat—and unlike the USSR, China is economically formidable.

More to the point, perceived existential stakes don’t answer my question. If the threat were greater, would we suddenly liberalize immigration, expand trade, and fund universities? Unlikely. A more plausible scenario is that if the threat were greater, we would restrict harder—more tariffs, less immigration, more internal conflict.

Several commenters, including my colleague Garett Jones, pointed to demographics—especially voter demographics. The median age has risen from 30 in 1950 to 39 in recent years; today’s older, wealthier, more diverse electorate may be more risk-averse and inward-looking. There’s something to this, but it’s not sufficient. Changes in the X variables haven’t been enough to explain the change in response given constant Betas so demography doesn’t push that far but does it even push in the right direction?

Age might correlate with risk-aversion, for example, but the Trump coalition isn’t risk-averse—it’s angry and disruptive, pushing through bold and often rash policy changes.

A related explanation is that the U.S. state has far less fiscal and political slack today than it did in 1957. As I argued in Launching, we’ve become a warfare–welfare state—possibly at the expense of being an innovation state. Fiscal constraints are real, but the deeper issue is changing preferences. It’s not that we want to return to the moon and can’t—it’s that we’ve stopped wanting to go.

In my view, the best explanation for the starkly different responses to the Sputnik and DeepSeek moments is the rise of zero-sum thinking—the belief that one group’s gain must come at another’s expense. Chinoy, Nunn, Sequiera and Stantcheva show that the zero sum mindset has grown markedly in the U.S. and maps directly onto key policy attitudes.

Zero sum thinking fuels support for trade protection: if other countries gain, we must be losing. It drives opposition to immigration: if immigrants benefit, natives must suffer. And it even helps explain hostility toward universities and the desire to cut science funding. For the zero-sum thinker, there’s no such thing as a public good or even a shared national interest—only “us” versus “them.” In this framework, funding top universities isn’t investing in cancer research; it’s enriching elites at everyone else’s expense. Any claim to broader benefit is seen as a smokescreen for redistributing status, power, and money to “them.”

Zero-sum thinking doesn’t just explain the response to China; it’s also amplified by the China threat. (hence in direct opposition to some of the above theories, the people who most push the idea that the China threat is existential are the ones who are most pushing the zero sum response). Davidai and Tepper summarize:

People often exhibit zero-sum beliefs when they feel threatened, such as when they think that their (or their group’s) resources are at risk…Similarly, working under assertive leaders (versus approachable and likeable leaders) causally increases domain-specific zero-sum beliefs about success….. General zero-sum beliefs are more prevalent among people who see social interactions as a competition and among people who possess personality traits associated with high threat susceptibility, such as low agreeableness and high psychopathy, narcissism and Machiavellianism.

Zero-sum thinking can also explain the anger we see in the United States:

At the intrapersonal level, greater endorsement of general zero-sum beliefs is associated with more negative (and less positive) affect, more greed and lower life satisfaction. In addition, people with general zero-sum beliefs tend to be overly cynical, see society as unjust, distrust their fellow citizens and societal institutions, espouse more populist attitudes, and disengage from potentially beneficial interactions.

…Together, these findings suggest a clear association between both types of zero-sum belief and well-being.

Focusing on zero-sum thinking gives us a different perspective on some of the demographic issues. In the United States, for example, the young are more zero-sum thinkers than the old and immigrants tend to be less zero-sum thinkers than natives. The likeliest reason: those who’ve experienced growth understand that everyone can get a larger slice from a growing pie while those who have experienced stagnation conclude that it’s us or them.

The looming danger is thus the zero-sum trap: the more people believe that wealth, status, and well-being are zero-sum, the more they back policies that make the world zero-sum. Restricting trade, blocking immigration, and slashing science funding don’t grow the pie. Zero-sum thinking leads to zero-sum policies, which produce zero-sum outcomes—making the zero sum worldview a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Someday I want to see the regressions

Each infant born from the procedure carries DNA from a man and two women. It involves transferring the nucleus from the fertilised egg of a woman carrying harmful mitochondrial mutations into a donated egg from which the nucleus has been removed.

For some carriers this is the only option because conventional IVF does not produce enough healthy embryos to use after pre-implantation diagnosis.

The researchers consistently reject the popular term “three-parent babies”, said Turnbull, “but it doesn’t make a scrap of difference.”

Here is more from Clive Cookson at the FT. From Newcastle. And here is some BBC coverage.

A Unifying Framework for Robust and Efficient Inference with Unstructured Data

This paper presents a general framework for conducting efficient inference on parameters derived from unstructured data, which include text, images, audio, and video. Economists have long used unstructured data by first extracting low-dimensional structured features (e.g., the topic or sentiment of a text), since the raw data are too high-dimensional and uninterpretable to include directly in empirical analyses. The rise of deep neural networks has accelerated this practice by greatly reducing the costs of extracting structured data at scale, but neural networks do not make generically unbiased predictions. This potentially propagates bias to the downstream estimators that incorporate imputed structured data, and the availability of different off-the-shelf neural networks with different biases moreover raises p-hacking concerns. To address these challenges, we reframe inference with unstructured data as a problem of missing structured data, where structured variables are imputed from high-dimensional unstructured inputs. This perspective allows us to apply classic results from semiparametric inference, leading to estimators that are valid, efficient, and robust. We formalize this approach with MAR-S, a framework that unifies and extends existing methods for debiased inference using machine learning predictions, connecting them to familiar problems such as causal inference. Within this framework, we develop robust and efficient estimators for both descriptive and causal estimands and address challenges like inference with aggregated and transformed missing structured data-a common scenario that is not covered by existing work. These methods-and the accompanying implementation package-provide economists with accessible tools for constructing unbiased estimators using unstructured data in a wide range of applications, as we demonstrate by re-analyzing several influential studies.

That is from a recent paper by Jacob Carlson and Melissa Dell. Via Kevin Bryan.

*Breakneck: China’s Quest to Engineer the Future*

Trump Administration Launches Probe Into Yale’s Use of Hacked EJMR Data

Christopher Brunet offers his version of the story. While I believe the original research methods were unethical, I very much prefer not to have the federal government involved in this matter.

Hayek Goes Supersonic

When I post about lifting the ban on supersonic flight, smart commenters show up with charts: optimal fuel burn is at Mach 0.78–0.84, they say, or no one wants to pay thousands to save a few hours. Maybe. But my reply is always the same: Bottled water!

In 2024, Americans spent $47 billion a year on H₂O that they could get for nearly free. That still boggles my mind—but bottled water has passed the market test. I argue for lifting the SST ban, and similar policies, not because we know supersonics will work but because we don’t. Hayek reminds us that competition is a discovery procedure. Like science, markets generate knowledge by experiment—hypotheses are posted as prices, and the public accepts or rejects them through revealed preference. Fred Smith’s FedEx plan got a “C” in the classroom, but the market graded the experiment and returned an A in equity. Theory is great, but just as in science, there is no substitute for running the experiment.

Supersonics Takeoff!

In Lift the Ban on Supersonics I wrote:

Civilian supersonic aircraft have been banned in the United States for over 50 years! In case that wasn’t clear, we didn’t ban noisy aircraft we banned supersonic aircraft. Thus, even quiet supersonic aircraft are banned today. This was a serious mistake. Aside from the fact that the noise was exaggerated, technological development is endogenous.

If you ban supersonic aircraft, the money, experience and learning by doing needed to develop quieter supersonic aircraft won’t exist. A ban will make technological developments in the industry much slower and dependent upon exogeneous progress in other industries.

When we ban a new technology we have to think not just about the costs and benefits of a ban today but about the costs and benefits on the entire glide path of the technology

In short, we must build to build better. We stopped building and so it has taken more than 50 years to get better. Not learning, by not doing.

… I’d like to see the new administration move forthwith to lift the ban on supersonic aircraft. We have been moving too slow.

Thus, I am pleased to note that President Trump has issued an executive order to lift the ban on supersonics!

The United States stands at the threshold of a bold new chapter in aerospace innovation. For more than 50 years, outdated and overly restrictive regulations have grounded the promise of supersonic flight over land, stifling American ingenuity, weakening our global competitiveness, and ceding leadership to foreign adversaries. Advances in aerospace engineering, materials science, and noise reduction now make supersonic flight not just possible, but safe, sustainable, and commercially viable. This order begins a historic national effort to reestablish the United States as the undisputed leader in high-speed aviation. By updating obsolete standards and embracing the technologies of today and tomorrow, we will empower our engineers, entrepreneurs, and visionaries to deliver the next generation of air travel, which will be faster, quieter, safer, and more efficient than ever before.

…The Administrator of the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) shall take the necessary steps, including through rulemaking, to repeal the prohibition on overland supersonic flight in 14 CFR 91.817 within 180 days of the date of this order and establish an interim noise-based certification standard, making any modifications to 14 CFR 91.818 as necessary, as consistent with applicable law. The Administrator of the FAA shall also take immediate steps to repeal 14 CFR 91.819 and 91.821, which will remove additional regulatory barriers that hinder the advancement of supersonic aviation technology in the United States.

Congratulations to Eli Dourado who has been pushing this issue for more than a decade.

Ideological Reversals Amongst Economists

Research in economics often carries direct political implications, with findings supporting either right-wing or left-wing perspectives. But what happens when a researcher known for publishing right-wing findings publishes a paper with left-wing findings (or vice versa)? We refer to these instances as ideological reversals. This study explores whether such researchers face penalties – such as losing their existing audience without attracting a new one – or if they are rewarded with a broader audience and increased citations. The answers to these questions are crucial for understanding whether academia promotes the advancement of knowledge or the reinforcement of echo chambers. In order to identify ideological reversals, we begin by categorizing papers included in meta-analyses of key literatures in economics as “right” or “left” based on their findings relative to other papers in their literature (e.g., the presence or absence of disemployment effects in the minimum wage literature). We then scrape the abstracts (and other metadata) of every economics paper ever published, and we deploy machine learning in order to categorize the ideological implications of these papers. We find that reversals are associated with gaining a broader audience and more citations. This result is robust to a variety of checks, including restricting analysis to the citation trajectory of papers already published before an author’s reversal. Most optimistically, authors who have left-to-right (right-to-left) reversals not only attract a new rightwing (left-wing) audience for their recent work, this new audience also engages with and cites the author’s previous left-wing (right-wing) papers, thereby helping to break down echo chambers.

That is from a new paper by Matt Knepper and Brian Wheaton, via Kris Gulati. If it is audience-expanding for researchers to write such papers, does that mean we should trust their results less?