Category: Uncategorized

The United States as a Developing Nation

In the decades between 1850 and 1950, the United States decisively transformed its place in the world economic order. In 1850, the US was primarily a supplier of slave-produced cotton to industrializing Europe. American economic growth thus remained embedded in established patterns of Atlantic commerce. One hundred years later, the same country had become the world’s undisputed industrial leader and hegemonic provider of capital. Emerging victorious from the Second World War, the US had displaced Britain as the power most prominently situated — even more so than its Cold War competitor — to impress its vision of a global political economy upon the world. If Britain’s industrial revolution in the late eighteenth century marked the beginning of a ‘Great Divergence’ (Pomeranz) of ‘the West’ from other regions around the world, American ascendance in the decades straddling the turn of the twentieth century marked a veritable ‘second great divergence’ (Beckert) that established the US as the world’s leading industrial and imperial power.

That is an excerpt from a new essay in Past and Present by Stefan Link and Noam Maggor. (You’ll find the best summary of the actual thesis in the last few pages of the piece, not in the beginning.) It is one of the more interesting economic history pieces I have read in some time. The pointer is from Pseudoerasmus, who also has been doing some running commentary on the article in his afore-linked Twitter feed.

Wednesday New Year’s assorted links

1. Evidence that puffins use tools. Good evidence. With videos.

2. Facts about Korea (recommended).

3. Esports predictions for 2020?

4. Is drinking going out of fashion? (The Economist)

5. Gordon Wood responds to the NYT.

What libertarianism has become and will become — State Capacity Libertarianism

Having tracked the libertarian “movement” for much of my life, I believe it is now pretty much hollowed out, at least in terms of flow. One branch split off into Ron Paul-ism and less savory alt right directions, and another, more establishment branch remains out there in force but not really commanding new adherents. For one thing, it doesn’t seem that old-style libertarianism can solve or even very well address a number of major problems, most significantly climate change. For another, smart people are on the internet, and the internet seems to encourage synthetic and eclectic views, at least among the smart and curious. Unlike the mass culture of the 1970s, it does not tend to breed “capital L Libertarianism.” On top of all that, the out-migration from narrowly libertarian views has been severe, most of all from educated women.

There is also the word “classical liberal,” but what is “classical” supposed to mean that is not question-begging? The classical liberalism of its time focused on 19th century problems — appropriate for the 19th century of course — but from WWII onwards it has been a very different ballgame.

Along the way, I believe the smart classical liberals and libertarians have, as if guided by an invisible hand, evolved into a view that I dub with the entirely non-sticky name of State Capacity Libertarianism. I define State Capacity Libertarianism in terms of a number of propositions:

1. Markets and capitalism are very powerful, give them their due.

2. Earlier in history, a strong state was necessary to back the formation of capitalism and also to protect individual rights (do read Koyama and Johnson on state capacity). Strong states remain necessary to maintain and extend capitalism and markets. This includes keeping China at bay abroad and keeping elections free from foreign interference, as well as developing effective laws and regulations for intangible capital, intellectual property, and the new world of the internet. (If you’ve read my other works, you will know this is not a call for massive regulation of Big Tech.)

3. A strong state is distinct from a very large or tyrannical state. A good strong state should see the maintenance and extension of capitalism as one of its primary duties, in many cases its #1 duty.

4. Rapid increases in state capacity can be very dangerous (earlier Japan, Germany), but high levels of state capacity are not inherently tyrannical. Denmark should in fact have a smaller government, but it is still one of the freer and more secure places in the world, at least for Danish citizens albeit not for everybody.

5. Many of the failures of today’s America are failures of excess regulation, but many others are failures of state capacity. Our governments cannot address climate change, much improve K-12 education, fix traffic congestion, or improve the quality of their discretionary spending. Much of our physical infrastructure is stagnant or declining in quality. I favor much more immigration, nonetheless I think our government needs clear standards for who cannot get in, who will be forced to leave, and a workable court system to back all that up and today we do not have that either.

Those problems require state capacity — albeit to boost markets — in a way that classical libertarianism is poorly suited to deal with. Furthermore, libertarianism is parasitic upon State Capacity Libertarianism to some degree. For instance, even if you favor education privatization, in the shorter run we still need to make the current system much better. That would even make privatization easier, if that is your goal.

6. I will cite again the philosophical framework of my book Stubborn Attachments: A Vision for a Society of Free, Prosperous, and Responsible Individuals.

7. The fundamental growth experience of recent decades has been the rise of capitalism, markets, and high living standards in East Asia, and State Capacity Libertarianism has no problem or embarrassment in endorsing those developments. It remains the case that such progress (or better) could have been made with more markets and less government. Still, state capacity had to grow in those countries and indeed it did. Public health improvements are another major success story of our time, and those have relied heavily on state capacity — let’s just admit it.

8. The major problem areas of our time have been Africa and South Asia. They are both lacking in markets and also in state capacity.

9. State Capacity Libertarians are more likely to have positive views of infrastructure, science subsidies, nuclear power (requires state support!), and space programs than are mainstream libertarians or modern Democrats. Modern Democrats often claim to favor those items, and sincerely in my view, but de facto they are very willing to sacrifice them for redistribution, egalitarian and fairness concerns, mood affiliation, and serving traditional Democratic interest groups. For instance, modern Democrats have run New York for some time now, and they’ve done a terrible job building and fixing things. Nor are Democrats doing much to boost nuclear power as a partial solution to climate change, if anything the contrary.

10. State Capacity Libertarianism has no problem endorsing higher quality government and governance, whereas traditional libertarianism is more likely to embrace or at least be wishy-washy toward small, corrupt regimes, due to some of the residual liberties they leave behind.

11. State Capacity Libertarianism is not non-interventionist in foreign policy, as it believes in strong alliances with other relatively free nations, when feasible. That said, the usual libertarian “problems of intervention because government makes a lot of mistakes” bar still should be applied to specific military actions. But the alliances can be hugely beneficial, as illustrated by much of 20th century foreign policy and today much of Asia — which still relies on Pax Americana.

It is interesting to contrast State Capacity Libertarianism to liberaltarianism, another offshoot of libertarianism. On most substantive issues, the liberaltarians might be very close to State Capacity Libertarians. But emphasis and focus really matter, and I would offer this (partial) list of differences:

a. The liberaltarian starts by assuring “the left” that they favor lots of government transfer programs. The State Capacity Libertarian recognizes that demands of mercy are never ending, that economic growth can benefit people more than transfers, and, within the governmental sphere, it is willing to emphasize an analytical, “cold-hearted” comparison between government discretionary spending and transfer spending. Discretionary spending might well win out at many margins.

b. The “polarizing Left” is explicitly opposed to a lot of capitalism, and de facto standing in opposition to state capacity, due to the polarization, which tends to thwart problem-solving. The polarizing Left is thus a bigger villain for State Capacity Libertarianism than it is for liberaltarianism. For the liberaltarians, temporary alliances with the polarizing Left are possible because both oppose Trump and other bad elements of the right wing. It is easy — maybe too easy — to market liberaltarianism to the Left as a critique and revision of libertarians and conservatives.

c. Liberaltarian Will Wilkinson made the mistake of expressing enthusiasm for Elizabeth Warren. It is hard to imagine a State Capacity Libertarian making this same mistake, since so much of Warren’s energy is directed toward tearing down American business. Ban fracking? Really? Send money to Russia, Saudi Arabia, lose American jobs, and make climate change worse, all at the same time? Nope.

d. State Capacity Libertarianism is more likely to make a mistake of say endorsing high-speed rail from LA to Sf (if indeed that is a mistake), and decrying the ability of U.S. governments to get such a thing done. “Which mistakes they are most likely to commit” is an underrated way of assessing political philosophies.

You will note the influence of Peter Thiel on State Capacity Libertarianism, though I have never heard him frame the issues in this way.

Furthermore, “which ideas survive well in internet debate” has been an important filter on the evolution of the doctrine. That point is under-discussed, for all sorts of issues, and it may get a blog post of its own.

Here is my earlier essay on the paradox of libertarianism, relevant for background.

Happy New Year everyone!

Who were the two most powerful and effective orators of the decade?

My picks and Trump and Greta Thunberg, in that order, as explained in my latest Bloomberg column. Excerpt:

My choice for second place is Greta Thunberg. In little more than a year, Thunberg has moved from being an unheard-of 16-year-old Swedish girl to Time’s Person of the Year. While she is now a social media phenomenon, her initial ascent was driven by her public speaking. Communication is quite simply what she does.

As a public speaker, Thunberg is memorable. The unusual prosody of autistic voices is sometimes considered a disadvantage, but she has turned her voice and her extreme directness into an unforgettably bracing style. She communicates urgency and moral seriousness on climate change at a time when the world is not taking decisive action. She mixes anger and condemnation with the look of a quite innocent young girl. Her Swedish version of a British accent is immediately recognizable. There is usually no one else in the room who looks or acts like her.

Her core speech she can give in about five minutes, perfect for an age of limited attention spans. She speaks in short, clipped phrases, each one perfect word-for-word. It is easy to excerpt discrete sentences on social media or on television.

As for memorable phrases, how about these: “I don’t want your hope.” “Did you hear what I just said?” “I want you to panic.” And of course: “How dare you? You have stolen my dreams and my childhood with your empty words.”

These days, you can simply say the name “Greta” in many parts of the world, and people will know who you are referring to.

You will note that under the formal DSM definition of autism, deficits in communication are a fundamental feature of the condition — perhaps that should be changed? Greta uses the term “selective mutism” in describing herself, but clearly the actual reality is more than just a simple deficit, rather an uneven pattern with very high peaks. As I wrote in the column, communicating is what she does.

One other point — I frequently hear or read people charge that Greta is being manipulated by her parents. I have no real knowledge of the Thunberg family, but in the research literature on prodigies it is clear that virtually all of those who have achieved something early had quite extreme self-motivation, a common feature of autism I might add.

Tuesday assorted non-links and links

1. Cocoman’s Law?: “The more important is an investigation of applied synthetic knowledge, the less useful literature there will be.”

2. E. Glen Weyl summary of RadicalxChange as an intellectual and political program.

3. How to hypothetically hack your school’s surveillance of you.

4. Ledwich and Zaitsev respond on YouTube radicalization.

5. New French board game on wealth gap is a big hit.

6. The value of air filters in classrooms, to limit air pollution.

The great Lemin Wu reemerges

Very loyal readers may recall that Lemin Wu was a Berkeley Ph.D in economic history and a student of Brad DeLong. Then he seemed to disappear. But for the last few years he was been working and writing, and later in 2020 he has a book coming out in China, in Chinese, title still undetermined.

I have read only parts of the book (the parts in English), and an outline. Still , I am willing to predict it will be the best and most important economics book of the year, in any language. It also likely will mark the first time a Chinese economist, writing in Chinese, created an important work.

I won’t “give away the plot,” but suffice to say it is about the rise of the West, the Malthusian model, group selection in history, why development takes so long, and related big topics. Oh, and it does tie in to and draw upon Cixin Liu’s The Three-Body Problem, just in case you were wondering.

I hope very much this book will be published in English as well.

Hail Lemin Wu!

What to think about Modi these days

Ian Bremmer offers one account of all the wrongdoing, which I will not summarize here. In any case, many of you have asked me what I think of these recent events.

I do not at all favor replacing India’s secular democracy with “Hindu nation” as a ruling principle. For one thing, I believe in strong libertarian protections for minority rights against state power, including for Muslims. I also believe these moves will be bad for India’s economy. Nonetheless I find most of the extant commentary on Modi fairly misleading and/or naive.

As this outsider sees it, India’s secular democracy was never liberal. It had certain de facto liberal elements, but largely out of low levels of state capacity, necessitating a kind of tolerance but of course also leading to a very sub-par infrastructure. Furthermore, it has been commonly described by political scientists as a “democracy without accountability.” National voting has so much to do with religion, caste, and other particularistic principles that Indian democracy never enforced superior practical performance as it should have.

Then enter several forces at more or less the same time, including Modi, ongoing Indian economic growth, higher expectations and thus greater demands for state capacity, a rise in what is called “populism,” and also an increase in the focality of Islam and also terrorism around the world.

In essence that state capacity starts to be built and part of it is turned to wrong ends, in an attempt to appeal to the roughly 80 percent Hindu majority. Here is the NYT:

The Modi administration has also done a better job than previous governments in pushing big anti-poverty initiatives, such as building 100 million toilets to help stop open defecation and the spread of deadly disease.

In other words, the positive and negative sides of the story here may be more closely related than is comfortable to contemplate. The picture reminds me a bit of how parts of Renaissance Europe were often more anti-Semitic or racist than medieval Europe, in part because persecuting states had more resources and it was easier to mobilize intolerant sentiment, partly due to the printing press. I don’t however idolize medieval times as being so libertarian, rather the earlier ideology contained the seeds of the Renaissance oppressions, which in time turned into foreign imperialism as well.

Similarly, oppression and religious conflict is hardly news in India, for instance you may recall the Partition which in the 1940s killed at least one million people and displaced at least 10 million more.

None of this is to excuse any of these oppressions, whether in India or elsewhere. The libertarian rights still ought to apply, and should be written into the Indian constitution and laws more firmly.

(It is an interesting and much under-discussed result that the greatest violations of libertarian rights tend to come in periods of high delta in state capacity, not high absolute levels of state capacity per se. The Nazi government was not that large as a percentage of gdp, but it was growing rapidly in terms of its efficacy along certain dimensions.)

The moral and resonant message here is “libertarian rights for minorities truly are important and beware state power!” And somehow we need to think strategically, at a deep level, how that message can be combined with the inevitable and indeed desirable growth in Indian state capacity. The libertarians only make this their issue by eliding the need for growth in state capacity. So they moralize correctly about the situation, but they don’t see the underlying dilemma so clearly either.

Consider this NYT passage:

“Modi is not a normal politician who measures his success only by votes,” said Kanchan Chandra, a political scientist at New York University. “He sees himself as the architect of a new India, built on a foundation of technological, cultural, economic and military prowess, and backed by an ideology of Hindu nationalism.”

The real question here is — still mostly unanswered — “what else is the new ideology of state capacity supposed to be?” I am happy to put in my vote for Anglo-American liberalism, but still I recognize that probably will not command either a majority or even a plurality.

Here is one proffered alternative to Modi:

“Rahul Gandhi felt people would support the Congress on issues of farmers, youth, employment, inflation. But, the core issues were left behind and surgical strikes and nationalism were highlighted. The Congress was dubbed a Muslim party. Aren’t we nationalists?” Gehlot asked.

I am not so impressed. Or try this discussion “What is alternative to ‘Modi cult'”. Again, on the ideas front underwhelming, at least for this classical liberal. Maybe something good can come out of the current protest movement (NYT).

All the more, the “establishment media” just isn’t interested in framing the story in terms of individual rights and constraints on democracy. That narrative is too…well…libertarian and also anti-statist.

For one example, blame either Nilinjana Roy or the person who titled her FT column “Democracy in India is on the brink.” Last I checked, Modi was elected, then re-elected, and his party and its allies control almost 2/3 of the lower house. That is truly an Orwellian column title. It should not be so hard to write “The problem with Modi is the statism, and lack of respect for minority rights, sadly this is democratically certified and thus democracy requires real constitutional constraint of the powers of the government.” But so many people today are mentally and emotionally incapable of thinking and writing such thoughts, having spent so much time in their mood affiliation glorifying “democracy” (or what they take to be democracy) above all other values.

So we should be spending our time developing and publicizing a new (non-Modi) ideology for greater state capacity in India, combined of course with greater liberty.

And yes, please do restore, redefine, re-enforce or in some cases discover all of the required minority libertarian rights. Hundreds of millions of Indians and others are counting on it.

Monday assorted links

My Conversation with Abhijit Banerjee

I had an excellent time in this one, here is the audio and transcript. Here is the opening summary:

Abhijit joined Tyler to discuss his unique approach to economics, including thoughts on premature deindustrialization, the intrinsic weakness of any charter city, where the best classical Indian music is being made today, why he prefers making Indian sweets to French sweets, the influence of English intellectual life in India, the history behind Bengali leftism, the best Indian regional cuisine, why experimental economics is underrated, the reforms he’d make to traditional graduate economics training, how his mother’s passion inspires his research, how many consumer loyalty programs he’s joined, and more.

Yes there was plenty of economics, but I feel like excerpting this bit:

COWEN: Why does Kolkata have the best sweet shops in India?

BANERJEE: It’s a bit circular because, of course, I tend to believe Kolkata has —

COWEN: So do I, however, and I have no loyalty per se.

BANERJEE: I think largely because Kolkata actually also — which is less known — has absolutely amazing food. In general, the food is amazing. Relative to the rest of India, Kolkata had a very large middle class with a fair amount of surplus and who were willing to spend money on. I think there were caste and other reasons why restaurants didn’t flourish. It’s not an accident that a lot of Indian restaurants were born out of truck stops. These are called dhabas.

COWEN: Sure.

BANERJEE: Caste has a lot to do with it. But sweets are just too difficult to make at home, even though lots of people used to make some of them. And I think there was some line that was just permitted that you can have sweets made out of — in these specific places, made by these castes.

There’s all kinds of conversations about this in the early-to-mid 19th century on what you can eat out, what is eating out, what can you buy in a shop, et cetera. I think in the late 19th century you see that, basically, sweet shops actually provide not just sweets, but for travelers, you can actually eat a lunch there for 50 cents, even now, an excellent lunch. They’re some savories and a sweet — maybe for 40 rupees, you get all of that.

And it was actually the core mechanism for reconciling Brahminical cultures of different kinds with a certain amount of social mobility. People came from outside. They were working in Kolkata. Kolkata was a big city in India. All the immigrants came. What would they eat? I think a lot of these sweet shops were a place where you actually don’t just get sweets — you get savories as well. And savories are excellent.

In Kolkata, if you go out for the day, the safest place to eat is in a sweet shop. It’s always freshly made savories available. You eat the freshly made savories, and you get some sweets at the end.

COWEN: Are higher wage rates bad for the highest-quality sweets? Because rich countries don’t seem to have them.

BANERJEE: Oh no, rich countries have fabulous sweets. I mean, at France —

COWEN: Not like in Kolkata.

BANERJEE: France has fabulous sweets. I think the US is exceptional in the quality of the . . . let me say, the fact that you don’t get actually excellent sweets in most places —

And this on music:

BANERJEE: Well, I think Bengal was never the place for vocal. As a real, I would say a real addict of vocal Indian classical music, I would say Bengal is not, never the center of . . . If you look at the list of the top performers in vocal Indian classical music, no one really is a Bengali.

In instrumental, Bengal was always very strong. Right now, one of the best vocalists in India is a man who lives in Kolkata. His name is Rashid Khan. He’s absolutely fabulous in my view, maybe the best. On a good day, he’s the best that there is. He’s not a Bengali. He’s from Bihar, I think, and he comes and settles in Kolkata. I think a Hindi speaker by birth, other than a Bengali. So I don’t think Bengal ever had top vocalists.

It had top instrumentalists, and Ravi Shankar, Ali Akbar Khan, Nikhil Banerjee — these were all Bengali instrumentalists. Even now, I would say the best instrumentalists, a lot of them are either Bengali or a few of them are second . . . Vilayat Khan and Imrat Khan were the two great non-Bengali instrumentalists of that period, I would say, of the strings especially. And they both settled in Kolkata, so that their children grew up in Kolkata.

And the other great instrumentalists are these Kolkata-born. They went to the same high school as I did. There were these Kolkata-born, not of Bengali families, but from very much the same culture. So I think Kolkata still is the place which produces the best instrumentalists — sitarists, sarod players, et cetera.

COWEN: Why is the better vocal music so often from the South?

Definitely recommended, Abhijit was scintillating throughout.

*Capital and Ideology*, by Thomas Piketty

This book is more than 1000 pp., here are my impressions:

1. About 600 pp. of this book is a carefully done history of the accumulation and sometimes dissipation of wealth and property. You can evaluate that material without reference to any particular set of political views.

2. At some point the book veers into partisan issues such as the wealth tax. Many of those parts remain interesting, but it also becomes clear that Piketty is “out to lunch,” to wit (p.591):

To return to the Soviet attitude toward poverty, it is important to try to understand why the government took such a radical stance against all forms of private ownership of the means of production, no matter how small. Criminalizing carters and food peddlers to the point of incarcerating them may seem absurd, but there was a certain logic to the policy. Most important was the fear of not knowing where to stop. If one began by authorizing private ownership of small businesses, would one be able to set limits?

I can think of a less naive explanation of Soviet attitudes toward the private sector. Piketty also calls for “participatory socialism” (p.592), a dubious doctrine not to be confused with say Nordic social democracy. For instance, Sweden (among other countries) seems to have fairly extreme wealth inequality.

3. The sentence “Real wages are much higher in America than in Western Europe” does not come easily to his pen. Nor does “The United States is a remarkably successful innovator, let’s see what we can learn from that.” Or even “Raising wages is more important than merely limiting inequality.” Those seems to be banished thoughts in the Piketty intellectual universe.

4. The sections on Soviet and socialist experience can only be called “delusional.” In his account, if only a few political decisions had gone the other way, the USSR might have ended up on a path similar to that of Norway (p.603 and thereabouts).

You know, maybe you think that the inequalities of the current day are much worse than people had been expecting. but that should not revise your view of socialism and the Soviet Union, two matters fairly well settled by historical research.

5. Give these lenses, it is impossible for Piketty to offer any commentary on recent events (about the last 400 pp. of the book) that is anything other than distorted and unreliable. There is massive distrust of the wealthy in this book, and virtually no distrust of concentrated state power.

6. There is a considerable sum of useful and valuable material in this book, and I would not try to dissuade anyone inclined from reading it. Nonetheless I suspect its main import is as another sign of the growing compartmentalization of academic discourse — good work intermingled with highly questionable partisan material — and how so many academics, if the mood affiliation tilts in the right direction, will tolerate or even encourage that.

You can pre-order the book here.

Sunday assorted links

1. “This wearable vest grows a self-sustaining garden watered by your own urine.”

2. “A self-educated philosopher who never completed high school, Olavo has formed a new generation of conservative leaders in Brazil through an online philosophy course he has taught for 10 years.” Main story link here.

3. How to fall in love with modern classical music.

4. Mostly non-profit hospitals: “Atlantic Health System, whose CEO is the AHA’s chairman, Brian Gragnolati, has sued patients for unpaid bills thousands of times this year, court records show, including a family struggling to pay bills for three children with cystic fibrosis.”

Saturday assorted links

1. History of the factory that made the Scrabble tiles. For one thing, I had never known of the Poe connection.

2. “‘Intended to induce awe’: codpiece thrusts itself back into fashion.”

3. Phil Magness on the 1619 project.

4. America’s newest and largest shopping mall (NJ, NYT).

There is now a NIMBY index

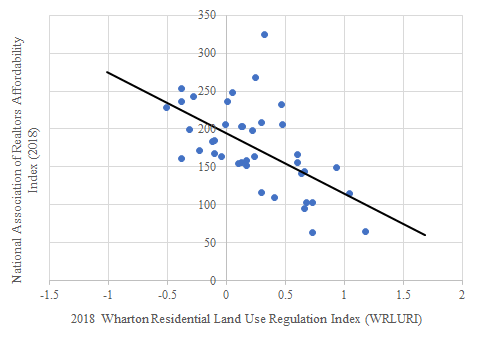

Check out the new NBER paper by Joseph Grourko, Jonathan Hartley, and Jacob Krimmel:

We report results from a new survey of local residential land use regulatory regimes for over 2,450 primarily suburban communities across the U.S. The most highly regulated markets are on the two coasts, with the San Francisco and New York City metropolitan areas being the most highly regulated according to our metric. Comparing our new data to that from a previous survey finds that the housing bust associated with the Great Recession did not lead any major market that previously was highly regulated to reverse course and deregulate to any significant extent. Moreover, regulation in most large coastal markets increased over time.

One embedded lesson is that the number of veto points over new construction is increasing. And “By our metric, about one half of all communities in the Regulation Change index increased regulation, one-third decreased, while only 18 percent showed no net change.”

Here is a graph of housing affordability vs. their index of restrictiveness:

Here is my earlier Bloomberg column calling for more indices — this is exactly what I wanted.

Friday assorted links

1. Shoplifters’ forum with discussion topics, some involving the idea of arbitrage.

2. Unconventional strategies for practicing Spanish.

3. The culture that is Sweden? Cook criticized for making food that is too tasty.

4. The culture that is (near) Maldon, Essex.

5. My two most read Bloomberg columns were on UFOs and Boomers.

6. Redux of a 2008 post: “For the people caught up in these intellectual traps, it all boils down to which groups of whiners they find most objectionable.”

Which researchers really work long hours?

No, not work smart but put in what would appear to be lots of extra hours. Why not measure who submits papers to journals in the off-work hours?:

Main outcome measures Manuscript and peer review submissions on weekends, on national holidays, and by hour of day (to determine early mornings and late nights). Logistic regression was used to estimate the probability of manuscript and peer review submissions on weekends or holidays.

Results The analyses included more than 49 000 manuscript submissions and 76 000 peer reviews. Little change over time was seen in the average probability of manuscript or peer review submissions occurring on weekends or holidays. The levels of out of hours work were high, with average probabilities of 0.14 to 0.18 for work on the weekends and 0.08 to 0.13 for work on holidays compared with days in the same week. Clear and consistent differences were seen between countries. Chinese researchers most often worked at weekends and at midnight, whereas researchers in Scandinavian countries were among the most likely to submit during the week and the middle of the day.

Emphasis added. Get this, you lazy bastards:

The average probability of a manuscript being submitted at the weekend for both journals was 0.14, and for a peer review it was 0.18. Peer review submissions during holidays had average probabilities of 0.13 (The BMJ) and 0.12 (BMJ Open), which were higher than the probabilities for manuscripts of 0.08 (The BMJ) and 0.10 (BMJ Open).

For weekend paper submission, China appears to be at about 0.22, India at about 0.09, see Figure 1. France, Italy, Spain, and Brazil all submit quite late in the afternoon, often a bit after 6 p.m.

That is from a new paper by Adrian Barnett, Inger Mewburn, and Sara Schroter. They do not tell us when they submitted it, but I wrote this blog post a wee bit after 8 p.m.

Via Michelle Dawson.