Assorted Gary Becker links

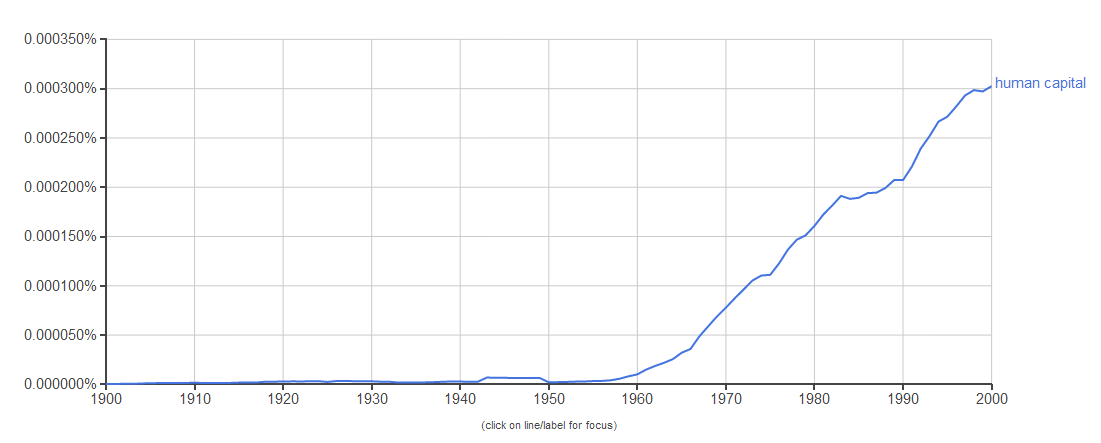

The Rise of Human Capital

No economist was more responsible for the appreciation, understanding and analysis of the fact that people invest in improving their productivity than was Gary Becker.

Some neglected Gary Becker open access pieces

Summarizing Becker’s contributions is like trying to summarize economics and it is not really possible. I believe he has the best “30th best” paper of any economist, living or dead.

Here are a few Becker articles which are not even his best known work:

1. “Irrational Behavior and Economic Theory.” Can the theorems of economics survive the assumption of irrational behavior? (hint: yes)

2. “Altruism, Egoism, and Genetic Fitness: Economics and Sociobiology.” The title says it all, from 1976.

3. “A Note on Restaurant Pricing and Other Examples of Social Influence on Price.” Why don’t successful restaurants just raise the prices for Saturday night seatings?

4. “The Quantity and Quality of Life and the Evolution of World Inequality” (with Philipson and Soares). The causes and importance of converging lifespans.

5. “Competition and Democracy.” From 1958, but most people still ignore this basic point about why government very often does not improve on market outcomes.

6. “The Challenge of Immigration: A Radical Solution.” Auction off the right to enter this country.

Assorted links

Gary Becker has passed away

Greg Mankiw offers the sad news. He was perhaps the greatest living economist.

Make three claims when trying to persuade

Suzanne B. Shu and Kurt A. Carlson have a paper (pdf) on this claim:

How many positive claims should be used to produce the most positive impression of a product or service? This article posits that in settings where consumers know that the message source has a persuasion motive, the optimal number of positive claims is three. More claims are better until the fourth claim, at which time consumers’ persuasion knowledge causes them to see all the claims with skepticism. The studies in this paper establish and explore this pattern, which is referred to as the charm of three. An initial experiment finds that impressions peak at three claims for sources with persuasion motives but not for sources without a persuasion motive. Experiment 2 finds that this occurs for attitudes and impressions, and that increases in skepticism after three claims explain the effect. Two final experiments examine the process by investigating how cognitive load and sequential claims impact the effect.

Here is a NYT summary of those results.

Rude salespeople make you buy fancy things

Here is a new result, although it is based on surveys rather than market data:

It’s no secret that salespeople at upscale shops can be a little snobbish, if not outright rude, the researchers note. Consumer complaints recently have pressured some luxury retailers to train their staffs to be more approachable; Louis Vuitton even went as far as decorating the entrance of its Beverly Hills store with a smiling cartoon apple in 2007. But if luxury retailers want to continue to rake in the dough, they actually should do the exact opposite, the study found. The ruder the salesperson the better.

In four online surveys, Ward and Dahl had participants imagine interactions with different types of salespeople under a bunch of different conditions. Variables included the imagined store’s level of luxury, the extent of the salesperson’s haughtiness, how well the salesperson represented the store’s brand, and how closely participants themselves related with the brand. The results:

- Rejection makes people want to buy luxury goods. A salesperson’s condescending attitude has little effect on consumers’ desire to buy more affordable brands like Gap and American Eagle, though.

- Rejection is stronger when salespeople convincingly embody brands in the way they act and dress. Sloppy salespeople aren’t as intimidating.

- People who really want to own a particular brand are even more influenced by rejection. Instead of switching their loyalties, customers just become more attached.

- Rejection works best in the short term. While great at pressuring people into buying something in the moment, dismissive staff may still alienate customers in the long run.

The results fall into a long line of research that demonstrates the extent to which rejection can jar our fragile self-conceptions.

The article is based on:

…a forthcoming study in theJournal of Consumer Research,Morgan Ward of Southern Methodist University and Darren Dahl of the Sauder School of Business…

The pointer is from Roman Hardgrave.

Department of Ho-Hum

Or should that read Department of Uh-Oh?:

Asteroids caused 26 nuclear-scale explosions in the Earth’s atmosphere between 2000 and 2013, a new report reveals.

Some were more powerful – in one case, dozens of times stronger – than the atom bomb blast that destroyed Hiroshima in 1945 with an energy yield equivalent to 16 kilotons of TNT.

Most occurred too high in the atmosphere to cause any serious damage on the ground. But the evidence was a sobering reminder of how vulnerable the Earth was to the threat from space, scientists said.

There is more here. You will find asteroid protection presented as the paradigmatic example of a public good in…um…my favorite Principles text.

Assorted links

1. Data on blockbuster movies.

2. Can China use its capital in a time of crisis?

3. My Piketty NYT column from July: “If you’d like to know where American political debates are headed, the data suggest a simple answer. The next major struggle — in economic terms at least — will be over whether taxes on personal wealth should rise — and by how much.” I believe this was the first coverage of Piketty in a major media outlet.

4. The prices of Qatari license plates.

5. First Bay area sex truck (what does this imply about living quarters?)

Cuba claims that plain tobacco packaging is anti-capitalist

Cuba has waded into the debate over plain tobacco packaging and has complained to the World Trade Organisation (WTO) over the UK’s plans.

According to a report in the Daily Telegraph, Cuba claimed that the law would be “anti-capitalist” and would threaten free trade. The Communist country added that plain packaging would lead to an increase in counterfeit cigarettes, leading to health risks to people smoking black market cigarettes.

Cuba’s letter to the WTO’s Committee to Technical Barriers on Trade concluded: “Cuba expresses great concern over the UK Parliament’s decision to move ahead with the process of implementation of plain packaging of tobacco products, without waiting for a settlement of the complaint against Australia before the WTO Dispute Settlement Body.”

That is not the silliest statement they have issued. There is more here, and for the pointer I thank R.

Stefan Homburg on Piketty

It is a useful overview (pdf, but better link here) of some of the major problems in the argument, here is one key passage:

Piketty’s erroneous claim is due to the implicit assumption that savings are never consumed, nor spent on charitable purposes or used to exert power over others. It is only under this outlandish premise that wealth grows at the rate r. If people use their savings later on, as they do in the Diamond model as well as in reality, the growth of wealth is independent of the return on capital. This holds all the more in the presence of taxes.

Piketty’s allegation that the relationship r>g implies a rising wealth-income ratio is not only logically flawed, however, but also rebutted by his own data: On p. 354, the author reports that the return on capital has consistently exceeded the world growth rate over the last 2,000 years. According to his “central contradiction of capitalism”, this would have implied steadily increasing wealth-income ratios. Yet, over the last two centuries or so, the period for which data are available, wealth-income ratios have remained relatively stable in countries like the United States or Canada. In countries such as Britain, France, or Germany, which were heavily affected by the wars, wealth-income ratios declined at the start of World War I and recovered after the end of World War II. The book’s references to these wars and the implied destruction of capital abound. They are intended to rescue the claim that r>g implies an ever rising wealth-income ratio. The United States and Canada as obvious counter-examples remain unmentioned in this context.

For the pointer I thank David Levey.

Assorted links

Does speaking a foreign language make us more utilitarian?

Albert Costa et.al. say yes:

Should you sacrifice one man to save five? Whatever your answer, it should not depend on whether you were asked the question in your native language or a foreign tongue so long as you understood the problem. And yet here we report evidence that people using a foreign language make substantially more utilitarian decisions when faced with such moral dilemmas. We argue that this stems from the reduced emotional response elicited by the foreign language, consequently reducing the impact of intuitive emotional concerns. In general, we suggest that the increased psychological distance of using a foreign language induces utilitarianism. This shows that moral judgments can be heavily affected by an orthogonal property to moral principles, and importantly, one that is relevant to hundreds of millions of individuals on a daily basis.

The Plos paper is here, hat tip from Vic Sarjoo. And here is another Robin Hanson post on “near vs. far.”

*Anarchy Unbound: Why Self-Governance Works Better Than You Think*

That is the new, forthcoming Peter Leeson book, available here.

Do social problems cause economic problems, or vice versa?

Some discussions stemming from Charles Murray and Paul Krugman raised this perennial issue a while ago. Some on the right suggest that economic struggles of middle class to lower class males (and females) stem from the social dysfunctionality of some of those males. An alternative view is that the lack of good jobs for such men is driving the social problems. Over at The Upshot, David Leonhardt reports on some recent evidence:

The behavior gap between rich and poor children, starting at very early ages, is now a well-known piece of social science. Entering kindergarten, high-income children not only know more words and can read better than poorer children but they also have longer attention spans, better-controlled tempers and more sensitivity to other children.

All of which makes the comparisons between boys and girls in the same categories fairly striking: The gap in behavioral skills between young girls and boys is even bigger than the gap between rich and poor.

By kindergarten, girls are substantially more attentive, better behaved, more sensitive, more persistent, more flexible and more independent than boys, according to a new paper from Third Way, a Washington research group. The gap grows over the course of elementary school and feeds into academic gaps between the sexes. By eighth grade, 48 percent of girls receive a mix of A’s and B’s or better. Only 31 percent of boys do.

I say if the problem has started that early, the social issues are unlikely to be purely derivative of the economic issues.