Indirect Bribing with Plausible Deniability

From a new working paper by Stefano Della Vigna, Ruben Durante, Brian Knight, and Eliana La Ferrara

We examine the evolution of advertising spending by firms over the period 1994 to 2009, during which Silvio Berlusconi was prime minister on and off three times, while maintaining control of Italy’s major private television network, Mediaset. We predict that firms attempting to curry favor with the government shift their advertising budget towards Berlusconi’s channels when Berlusconi is in power. Indeed, we document a significant pro-Mediaset bias in the allocation of advertising spending during Berlusconi’s political tenure. This pattern is especially pronounced for companies operating in more regulated sectors…

In the United States, Lyndon Johnson made his fortune, working through Lady Bird, in similar ways. As Robert Caro wrote in Means of Ascent:

As one businessman puts it: “Everyone knew that a good way to get Lyndon to help you with government contracts was to advertise over his radio station.”

Jack Shafer, drawing on Caro, summarizes the details in The Honest Graft of Lady Bird Johnson.

Hat tip: John van Reenen.

Freer trade in European and Spanish health care services

Spanish patients, like all Europeans, will now be able now choose which EU country to seek treatment in. The Cabinet last week approved a decree that implements an EU directive on cross-border healthcare. Under the system, patients will advance the money for their treatment abroad, but can request a reimbursement from their own country.

The directive aims to go one step beyond the emergency treatment already covered by the European Health Card and let patients choose another member state for specific, non-emergency treatment.

Spain however has concerns:

The State Council, the government’s key advisory body, has this week warned the government that the measure may put a major strain on Spain’s resources. “Given that our country is a recipient country for tourists, it seems likely that this could lead to an increase in demand for healthcare,” the State Council report on the law change says, which could result in “longer waiting lists.”

Additionally, reimbursement will not necessarily cover the total amount charged by the foreign hospital; instead Spanish authorities will use the official rates of each regional health service. Spain does not have a common set of rates; rather, each regional government sets its own public tariffs.

It might over time lead to higher prices. Here are some other possible implications:

Spain’s private health system could be the main beneficiary of this new system…This is because “prestigious and renowned” private health centers could get added clients now that member states have to reimburse their citizens. Of course foreigners could choose the public health system, but it would mean long waiting lists under the same conditions as Spanish patients.

Medical fees at both public and private hospitals in Spain are lower than in many other European countries. “It could well be that for Scandinavia it is cheaper to send patients to Spain,” notes Rivero.

There is more here. There is plenty of further information here, but only very recently has this cross-border directive been moving to a scale where it might make a real difference. Spain for instance seems to be a country which is cheap enough, sunny enough, and reliable enough to draw significant business.

Larry Summers on finance

It is certainly true that there has been a dramatic increase in the number of highly paid people in finance over the last generation. Recent studies reveal that most of the increase has resulted from an increase in the value of assets under management. (The percentage of assets that financiers take in fees has remained roughly constant.) Perhaps some policy could be found that would reduce these fees but the beneficiaries would be the owners of financial assets – a group that consists mainly of very wealthy people.

I hope you can fight through the FT gate here, the piece is interesting throughout.

Addendum: Ungated link is here.

Are genetics becoming more important for NBA success?

That’s hard to say, but a number of different models would predict that effect over time, as opportunities spread to a greater number of potential players. Here is a good article from Scott Cacciola:

For a growing number of fathers and sons, the N.B.A. is a family business. This season, 19 second-generation players have appeared in games — a total that represents 4.2 percent of the league, and is nearly twice as many players as a decade ago.

Consider that three second-generation players were selected to participate in Sunday night’s All-Star Game here: Stephen Curry of the Golden State Warriors, Kevin Love of the Minnesota Timberwolves and Kobe Bryant of the Los Angeles Lakers. (Bryant, voted in by the fans, will not play because of a knee injury.)

Even more progeny are on the way. Two of this country’s top college players — Andrew Wiggins, a freshman at Kansas, and Jabari Parker, a freshman at Duke — are sons of former N.B.A. players. Both are expected to be lottery picks whenever they decide to make themselves eligible for the draft.

Players and coaches cite several factors in the rise of second-generation players, who tend to benefit from genetics (it helps to be tall) and from early access to top-notch instruction. Steve Kerr, a former guard and front-office executive, likened the setting to being immersed in a “basketball think tank” from childhood.

Assorted links

1. Crowdsource dating advice, while you are on dates.

2. Seinfeld vs. LCD Soundsystem, or why many people succeed in their late 30s.

3. Extending unemployment benefits did increase joblessness, and the paper is here (pdf).

4. What really went wrong with the microfoundations of macroeconomics? Chris House writes: “The main thing New Keynesian research has been devoted to for the past 20 years is an exhaustive study of price rigidity. If anything was holding us back it was the extraordinary devotion of our energy and attention to the study of nominal rigidities. We now know more about the details of price setting than any other field in economics. As financial markets were melting down in 2008, many of us were regretting that allocation of our attention. We really needed a more refined empirical and theoretical understanding of how financial markets did or did not work.”

5. Chopin’s Heart.

Practical gradualism vs. moral absolutism, for immigration and revolution

After reading Alex’s post I was a bit worried I would wake up this morning and find the blog retitled, maybe with a new subtitle too. Just a few quick points:

1. There is a clear utilitarian case against open borders, namely that it will — in some but not all cases — lower the quality of governance and destroy the goose that lays the golden eggs. The world’s poor would end up worse off too. I wonder if Alex will apply his absolutist idea on fully open borders to say Taiwan.

2. Alex’s examples don’t support his case as much as he suggests. The American Revolution compromised drastically on slavery, among other matters. (And does Alex even favor that revolution? Should he? Can you be a moral absolutist on both that revolution and on slavery?) American slavery ended through a brutal war, not through the persuasiveness of moral absolutists per se. The British abolished slavery for off-shore islands, but they were very slow to dismantle colonialism, and would have been slower yet if not for two World Wars and fiscal collapse. Should the British anti-slavery movement have insisted that all oppressive British colonialism be ended at the same time? You may argue this one as you wish, but the point is one of empirics, not that the morally absolutist position is generally better.

3. Gay marriage is like “open borders for Canadians.” I’m for both, but I don’t see many people succeeding with the “let’s privatize marriage” or “let’s allow any consensual marriage” arguments, no matter what their moral or practical merits may be. Gay marriage advocates were wise to stick with the more practical case, again choosing an interior solution. Often the crusades which succeed are those which feel morally absolute to their advocates and which also seem like practically-minded compromises to moderates and the undecided.

4. Large numbers of important changes have come quite gradually, including women’s rights, protection against child abuse, and environmentalism, among others. I don’t for instance think parents should ever hit their children, but trying to make further progress on children’s rights by stressing this principle is probably a big mistake and counterproductive.

5. The strength of tribalist intuitions suggests that the moral arguments for fully open borders will have a tough time succeeding or even gaining basic traction in a world where tribalist sentiments have very often been injected into the level of national politics and where, nationalism, at least in the wealthier countries, is perceived as working pretty well. The EU is by far the biggest pro-immigration step we’ve seen, which is great, but we’re seeing the limits of how far that can be pushed. My original post gave some good evidence that a number of countries — though not the United States — are pretty close to the point of backlash from further immigration. Rather than engaging such evidence, I see many open boarders supporters moving further away from it.

6. In the blogosphere, is moralizing really that which needs to be raised in relative status?

Addendum: Robin Hanson adds comment.

And: Alex responds in the comments:

Some good points but only point number #5 actually addresses my argument. I argued that strong, principled moral arguments are most likely to succeed. Point #5 rests on mood affiliation. I know because having a different mood I read the facts in that point in entirely the opposite way. Namely that it’s amazing that although our moral instincts were built on the tribe we have managed to expand the moral circle far beyond the tribe. Having come so far I see no reason why we can’t continue to expand the moral circle to include all human beings. The open borders of the EU is indeed a triumph. Let’s create the same thing with Canada and then lets join with the EU.

Do not make the mistake (as in point #2) of thinking that the moral argument only succeeds when we make fully moral choices. It also succeeds by pushing people to move in the right direction when other arguments would not do that at all.

The cable television market is growing more contestable

The Satellite TV Providers industry is in the midst of a revolution, supplying popular family shows, news, movies, sports, documentaries and other products to a growing swarm of eager subscribers willing to pay for in-home entertainment. For example, the introduction of high-definition (HD) TV vastly improved the quality of shows and attracted subscribers even as disposable income dropped during the Great Recession. “In addition to a dramatically improved reputation for quality, new networks, channel offerings and bonus features are strengthening the industry’s appeal to consumers,” says IBISWorld industry analyst Doug Kelly. Higher spending on industry services is anticipated to result in 5.6% annualized revenue growth to $41.4 billion in the five years to 2012. This climb includes an expected 3.8% increase in 2012 as more consumers continue subscribing to satellite TV…

Over the next five years, the industry will face escalating competition from other media.

Have I mentioned Hulu TV and YouTube and Netflix, especially the non-broadband requiring discs? How about reading the internet? How about using your iPad to watch downloaded movies and TV shows? New social media for sharing? “Let them download somewhere else”? There is a reason why “cable” and “cord cutting” appear so frequently in the same sentence.

There is no big deal with Comcast acquiring Time Warner, also because the two companies serve separate districts. If anything the new consolidated entity will have stronger monopsony power over programs and can bid their prices down. (Isn’t ESPN with its sports contracts a monopoly of sorts, just as the sports leagues are?) We all know that monopolists facing lower marginal costs tend to lower price (contrary to Tim Wu), even if not by as much as we might like. Krugman worries that “This would, in turn, make it even harder for potential competitors to enter markets served by ComcastTimeWarner, strengthening its monopoly position.” A better sentence would have been “No five year period has so increased the contestability of the cable sector than the last five years in the United States.”

One might also add that if ComcastTimeWarner can bid down prices on programs, this need not keep out other competitors. Those programs are non-rivalrous in consumption, and the sellers can extend whatever price discounts they might wish to new competitors, to increase the demand for their products. The final equilibria here are complex, but in general the ability of a strong firm, in this setting, to bid down input prices is not a bad thing.

Addendum: If you wish to worry about something, it is how to get more competition within a single market, as you might for instance do through municipal wi-fi, the successor to 4G, and so on. Worrying about the horizontal spread of trading in one monopoly for another is beside the point. What I am seeing in various comments on Twitter is people with objections to cable monopolies, some of them valid objections, then objecting to possible changes in the market out of basic mood.

Assorted links

1. A Hindu nationalist explains his objections to the Wendy Doniger book. And why there isn’t more free speech in India.

3. Brand minimalism.

4. Is there yet further evidence that we live in a computer simulation?

5. Not good enough I suspect (this link is not quite safe for work).

The Moral Is the Practical

Tyler concedes the moral high ground to advocates of open borders but argues that the proposal is “doomed to fail and probably also to backfire in destructive ways.” In contrast, I argue that the moral high ground is tactically the best ground from which to launch a revolution. In Entrepreneurial Economics I wrote:

No one goes to the barricades for efficiency. For liberty, equality or fraternity, perhaps, but never for efficiency.

Contra Tyler, the lesson of history is that few things are as effective at launching a revolution as is moral argument. Without the firebrand Thomas “We have it in our power to begin the world over again“ Paine, the American Revolution would probably never have happened. Paine’s Common Sense, the most widely read book of its time, is about as far from Tyler’s synthetic, marginalist argument as one can imagine and it was effective.

When in 1787 Thomas Clarkson founded The Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade a majority of the world’s people were held in slavery or serfdom and slavery was considered by almost everyone as normal, as it had been considered for thousands of years and across many nations and cultures. Slavery was also immensely profitable and woven into the fabric of the times. Yet within Clarkson’s lifetime slavery would be abolished within the British Empire. Whatever one may say about this revolution one can certainly say that it was not brought about by a “synthetic and marginalist” approach. If instead of abolition, Clarkson had settled on the goal of providing for better living conditions for slaves on the voyage from Africa it seems quite possible that slavery would still be with us today.

When in 1787 Thomas Clarkson founded The Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade a majority of the world’s people were held in slavery or serfdom and slavery was considered by almost everyone as normal, as it had been considered for thousands of years and across many nations and cultures. Slavery was also immensely profitable and woven into the fabric of the times. Yet within Clarkson’s lifetime slavery would be abolished within the British Empire. Whatever one may say about this revolution one can certainly say that it was not brought about by a “synthetic and marginalist” approach. If instead of abolition, Clarkson had settled on the goal of providing for better living conditions for slaves on the voyage from Africa it seems quite possible that slavery would still be with us today.

In more recent times, civil unions have gone nowhere while equality of marriage has succeeded beyond all expectation. The problem with civil unions, and with the synthetic and marginalist approach more generally, is that even though it offers everyone something that they want, it concedes the moral high ground–perhaps there is something different about gay marriage which makes it ok to treat it differently–and for that reason it attracts few adherents. Moreover, the argument for civil unions doesn’t force the opposition to enunciate the moral arguments for their opposition and when the moral ground of the opposition is weak that is a strategic failure.

The moral argument for open borders is powerful. How can it be moral that through the mere accident of birth some people are imprisoned in countries where their political or geographic institutions prevent them from making a living? Indeed, most moral frameworks (libertarian, utilitarian, egalitarian, and others) strongly favor open borders or find it difficult to justify restrictions on freedom of movement. As a result, people who openly defend closed borders sound evil, even when they are simply defending what most people implicitly accept. When your opponents occupy ground that they cannot–even on their own moral premises–defend then it is time to attack.

*Fragile by Design*

That is the new banking book by Charles W. Calomiris and Stephen H. Haber and the subtitle is The Political Origins of Banking Crises & Scarce Credit. I went to review it, but came back to the thought that I liked Arnold Kling’s review better than what I was coming up with, here goes:

I am now reading Fragile by Design by Charles Calomiris and Stephen Haber. I posted a few months ago on an essay they wrote based on the book. I also attended yesterday an “econtalk live,” where Russ Roberts interviewed the authors in front of live audience for a forthcoming podcast. You might look forward to listening–the authors are very articulate and they speak colorfully, e.g. describing the United States as being “founded by troublemakers” who achieved independence through violence, as opposed to the more boring Canadians.

I think it is an outstanding book, although in my opinion it is marred by their focus on CRA lending as a cause of the recent financial crisis. This is a flaw because (a) they might be wrong and (b) even if they are right, they will turn off many potential readers who might otherwise find much to appreciate in the book. Everyone, regardless of ideology, should read the book. It offers a lot of food for thought.

I am only part-way through it. The story as far as I can tell is this:

1. There is a lot of overlap between government and banking. Governments, particularly as territories coalesced into nation states, needed to raise funds for speculative enterprises, such as wars and trading empires. Banks need to enforce contracts, e.g., by taking possession of collateral in the case of a defaulted loan. Government needs the banks, and the banks need government.

2. If the rulers are too powerful, they may not be able to credibly commit to leaving banks assets alone, so it may be hard for banks to form. But if the government is not powerful enough, it cannot credibly commit to enforcing debt contracts, so that it may be hard for banks to form.

3. Think of democracies as leaning either toward liberal or populist. By liberal, the authors mean Madisonian in design, to curb power in all forms. By populist, the authors mean responsive to the will of popular coalitions of what Madison called factions.

4. If you are lucky (as in Canada), your banking policies are grounded in a liberal version of democracy, meaning that the popular will is checked, and regulation serves to implement a stable banking system. If you are unlucky (as in the U.S.), your banking policies are grounded in the populist version of democracy. Banking policy reflects a combination of debtor-friendly interventionism and regulations that favor rent-seeking coalitions who shift burdens to taxpayers. The result is an unstable system.

I may not be stating point 4 in the most persuasive way. I am not yet persuaded by it. In fact, I think libertarians will be at least as troubled as progressives are by some of the theses that the authors promulgate.

Joseph Nocera calls me on the phone

On Friday, I called Tyler Cowen, the George Mason University economist (and a contributor to The New York Times) to ask what he thought about the relationship between technological innovation and jobs. He told me that he mostly agreed with Brynjolfsson and McAfee about the future, though he disagreed with their assessment of the past. (One of his recent books is titled “The Great Stagnation.”)

Yes, he said, technology would replace humans for certain kinds of jobs, but he could also envision growth in the service sector. “The jobs will be better than they sound,” he said. “A lot of them will require skill and training, and will also pay well. I think we’ll get to driverless cars and much better versions of Siri fairly soon,” he added. “That will make the rate of labor force participation go down.”

Then he chuckled. He had recently been in a meeting with someone, explaining his views. “So what you’re saying,” the man concluded, “is that the pessimists are right. But it’s going to be much better than they think.”

Arrived in my pile

1. Michael Szenberg and Lall Ramrattan, editors, Secrets of Economics Editors.

2. Joel Slemrod and Christian Gillitzer, Tax Systems.

Facebook is introducing more choices for gender identification

You don’t have to be just male or female on Facebook anymore. The social media giant is adding a customizable option with about 50 different terms people can use to identify their gender, as well as three preferred pronoun choices: him, her or them.

I’m all for this development, and I’ll note one extra thing: people who write on “the paradox of choice” are unlikely to ever use this as an example.

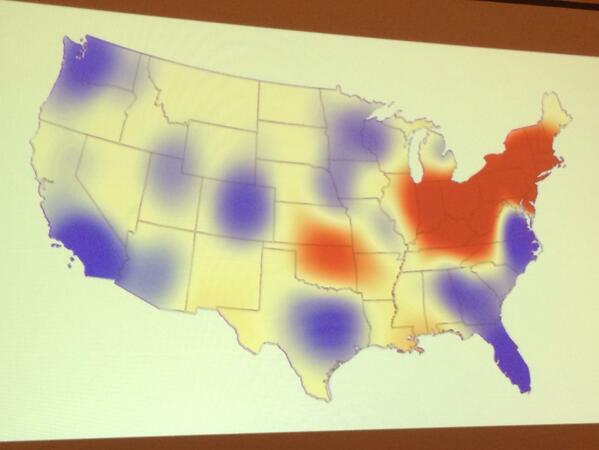

Personality by region

As indicated by words on blogs: red is high neurotic, blue is low. Highly speculative of course:

Assorted links

1. Dan Klein at The Atlantic on the history of the concept of liberalism, and the Scots tradition.

2. Lesser known improvements in the U.S. labor market. Also, proposed minimum wage hike to cover disabled workers.

3. Tandem-pawn chess, designed to put humans on an equal footing with computers.

4. The “hot hand” idea enjoys a resurgence.

5. Growing economies of scale in Bitcoin mining.

6. How a Pandora lawsuit may overturn the economics of the music industry.

7. Update on the Italian situation. And what is wrong with Finland?