What I’ve been reading

1. Dervla Murphy, Full Tilt: Ireland to India with a Bicycle. She covered 3000 miles in the 1960s, and as she notes in the introduction: “Epictetus put it in a nutshell when he said, “For it is not death or hardship that is a fearful thing, but the fear of death and hardship.” Self-recommending. But don’t be fooled by the title — hardly any of the narrative takes place in India.

2. David E. Bernstein, Classified: The Untold Story of Racial Classification in America . A scathing and unfortunately spot-on indictment of America’s schemes of racial classification. So often those schemes turn out to be racist themselves. The Hmong cannot count as an “underrepresented group” because they are Asian!? Come on, people. There is no good way to do this work, and I am pleased to see David pointing this out so effectively.

3. Nelly Sachs, Flight and Metamorphosis, Poems. A lovely bilingual edition, covering her less-known post-Holocaust poetry. The quality is still very high and the page display is excellent.

Serhi Plokhy, Atoms and Ashes: A Global History of Nuclear Disasters is exactly what the subtitle promises.

Fernanda Melchor, Paradais is a new Mexican novel that has received a lot of attention. I thought English was “not good enough for it,” though the slang and format would challenge my Spanish. If you can read this properly in Spanish, I suspect it is excellent.

Daisy Hay, Dinner with Joseph Johnson is a good book about the Enlightenment publisher who interacted with Blake, Wordsworth, Coleridge, Benjamin Franklin, Priestly, Fuseli, and Mary Wollstonecraft, among others.

Halik Kochanski, Resistance: The Underground War Against Hitler, 1939-1945. So far I have had time only to browse it, but it appears to be both excellent and definitive.

Saturday assorted links

1. Predictions for Britain in 2050.

2. A skeptical case on fusion.

3. Swiss woman fined for feeding her neighbor’s cat.

4. “Although most individuals with IQs ≤ 90 did not have a college degree, the rate at which they completed college had increased approximately 6-fold in men and 10-fold in women relative to rates in the previous generation.” And it seems to be good for them.

The magnitude of depolicing

Using a time regression discontinuity design, we estimate a 72.7 percent decrease in lower-level “quality of life” arrests, and a 69 percent decrease in non-index crime arrests in Minneapolis following George Floyd’s death. Our results also show that the decrease in arrests is driven by a 69 percent decrease in police-initiated calls for service. Using the same approach, we find a much smaller decrease of 2.7 percent in arrests and a 1.5 percent decrease in police calls following police-involved shootings. Our results, thus, suggest that the Ferguson Effect exists, and it is much larger following highly publicized events of police violence such as George Floyd’s death.

That is from the new AER, by Maya Mikdash and Reem Zaiour, “Does (All) Police Violence Cause De-policing? Evidence from George Floyd and Police Shootings in Minneapolis.” The title I find slightly Straussian, I hope not outright naive.

The paradox of auction happiness

If you win something at auction, even if you end up paying your full bid, you are typically quite happy, rather than just a smidgen happy.

Then why didn’t you bid more in the first place?

Is your mistake being too happy, or is your mistake having bid too low?

Do you become happy only by winning discrete, decent-sized lumps of happiness, rather than smidgens of happiness? Does that even make sense?

Or is it just the value of winning per se, in which case there might be some other artificial way of manufacturing the same feeling?

Note this all runs a bit counter to winner’s curse arguments, which suggest you should be a smidgen unhappy when you win, not when you lose.

How should we best model this?

Friday assorted links

The Unfairness Doctrine

The great George Will hits another one out of the ballpark with some useful reminders:

Government pratfalls such as the Disinformation Governance Board are doubly useful, as reminders of government’s embrace of even preposterous ideas if they will expand its power, and as occasions for progressives to demonstrate that there is no government expansion they will not embrace.

…Using radio spectrum scarcity as an excuse, even before the Fairness Doctrine was created, Republicans running Washington in the late 1920s pressured a New York station owned by the Socialist Party to show “due regard” for other opinions. What regard was “due”? The government knew. So, it prevented the Chicago Federation of Labor from buying a station, saying all stations should serve “the general public.”

In 1939, Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration conditioned one station’s license renewal on ending anti-FDR editorials. (Tulane Law School professor Amy Gajda’s new book, “Seek and Hide: The Tangled History of the Right to Privacy,” reports that earlier, FDR had “unsuccessfully pushed for a code of conduct for newspapers as part of the Depression-era National Recovery Act and had envisioned bestowing on compliant newspapers an image of a blue eagle as a sort of presidential seal of approval.”)

John F. Kennedy’s Federal Communications Commission harassed conservative radio, and when a conservative broadcaster said Lyndon B. Johnson used the Gulf of Tonkin incident in 1964 as an excuse for Vietnam escalation, the Fairness Doctrine was wielded to force the broadcaster to air a response.

Hat tip: Don Boudreaux at Cafe Hayek.

“NAIMBY” goes beyond just belling the cat

In April, Akureyri—the largest municipality in the country’s north, with a population of 19,000 people and some 2,000 to 3,000 cats—decided to ban their feline residents from night roaming outside. Neighboring Húsavík banned cats several years ago from going outdoors day and night. Other Icelandic towns are considering bans as the issue of free-roaming cats increasingly makes its way from online forums to local politics, with the arguments generally falling into two categories. Some people—the “no animals in my backyard” or NAIMBY-ists—proclaim free-roaming cats are nuisances that should be confined like any other pet. Others think beyond the anthropocentric: cats kill birds and disrupt ecosystems.

And:

Surveys suggest Icelanders’ support for cat curfews is highest in regions with private homes and private gardens. Their reasoning is predominantly idiosyncratic, likening roaming cats to visits from rowdy town drunks. To paraphrase some online comments about cat visitations: “cat urine sprayed the patio,” “challenged another cat to a 3:00 a.m. duel and killed the yellow daffodils,” “last week he came into the house, and the pharmacy is out of pet-allergy drugs.” Cat supporters reply along the lines of, “Get a life and try to tolerate the outside world; cats are a delight and have roamed Iceland as long as we have.”

Here is the full Icelandic story, from the always excellent The Browser. Is there a corresponding YAIMBY movement?

The fall of Sri Lanka

After the end of a devastating 26-year civil war in 2009, the island of 22mn had the makings of an Asian economic success story. Under governments run by the powerful Rajapaksa family, annual economic growth peaked at 9 per cent. By 2019, the World Bank had classified the island as an upper-middle income country. Sri Lankans enjoyed a per capita income double that of neighbours such as India, along with longer lifespans thanks to strong social services such as healthcare and education. The country tapped international debt lenders to rebuild, becoming a key private Asian bond issuer and participant in China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

And yet now everything is in tatters (that passage is from a very good FT piece). Here is one bit:

Sri Lanka’s reserves have fallen from $7.5bn in November 2019 to the point where finding $1mn is “a challenge”, Wickremesinghe, the new prime minister, said in an address last week. This has meant shortages of not only fuel but food and medicine, with hospitals forced to postpone surgeries. The country has the worst inflation in Asia at about 30 per cent in April and the currency has almost halved in value since it was floated in March. The UN Development Programme says that nearly half the population is in danger of falling below the poverty line, and warns of a looming humanitarian crisis as the urban poor and former middle class begin to cut back on meals.

And:

“Most people are down to one meal a day”, says her neighbour, Mohammad Akram, “but are embarrassed to admit it.”

I believe we have not yet internalized how rapidly a middle income country can fall from grace and into utter chaos.

Qubit teleportation between non-neighbouring nodes in a quantum network

Future quantum internet applications will derive their power from the ability to share quantum information across the network. Quantum teleportation allows for the reliable transfer of quantum information between distant nodes, even in the presence of highly lossy network connections. Although many experimental demonstrations have been performed on different quantum network platforms, moving beyond directly connected nodes has, so far, been hindered by the demanding requirements on the pre-shared remote entanglement, joint qubit readout and coherence times. Here we realize quantum teleportation between remote, non-neighbouring nodes in a quantum network. The network uses three optically connected nodes based on solid-state spin qubits. The teleporter is prepared by establishing remote entanglement on the two links, followed by entanglement swapping on the middle node and storage in a memory qubit. We demonstrate that, once successful preparation of the teleporter is heralded, arbitrary qubit states can be teleported with fidelity above the classical bound, even with unit efficiency. These results are enabled by key innovations in the qubit readout procedure, active memory qubit protection during entanglement generation and tailored heralding that reduces remote entanglement infidelities. Our work demonstrates a prime building block for future quantum networks and opens the door to exploring teleportation-based multi-node protocols and applications.

Here is the Nature paper, by S.L.N. Hermans, et.al., via the excellent Kevin Lewis.

Thursday assorted links

“A political football” takes on new meaning (MIE)

The concept and governance of name, image, and likeness has always been highly politicized. But the deals themselves have largely stayed out of politics — until now.

Dresser Winn, a quarterback at the University of Tennessee at Martin, has signed a partnership to support the candidacy of Colin Johnson, who is running for District Attorney General for Tennessee’s 27th Judicial District.

The deal is considered to be the first to support a political candidate. It’s also an example of how athletes who may not have major followings or a Power 5 platform can ink partnerships in their community, as one of Winn’s agents, Dale Hutcherson, pointed out on Twitter.

The deal was born when both of Winn’s agents, Dale and Sam Hutcherson, came up with the idea and presented it to him, he told Front Office Sports.

“I’ve been lifelong friends with Colin. He’s always supported me,” he said. From there, it was an easy decision to sign with the candidate.

As part of the partnership, Winn said he wore a campaign shirt during a football camp that he ran last weekend. On Monday, his announcement on Twitter included photos of himself and Johnson — both of whom were wearing campaign apparel — spending time on a football field. The tweet encouraged voters to ensure they were registered for the August election.

As for future promotions, Winn said they’re going to “see how things go from here.”

Winn declined to disclose financial terms of the deal.

America! Here is the full story, via Daniel Lippman.

The best arguments for and against the alien visitation hypothesis

Those are the subject of my latest Bloomberg column, about 2x longer than usual, WaPo link here. Excerpt, from the segment on arguments against:

The case against visits by aliens:

1. Alien sightings remain relatively rare.

Let’s say alien drone probes can make it here. That would imply the existence of a very advanced civilization that can span great distances and command energy with remarkable efficiency. If that’s the case, why isn’t the sky full of aliens? Why aren’t there sightings from more than just military craft?

So the question is not so much, “Why don’t we see aliens?” as, “Why don’t we see more of them?” It is a perfectly valid (and embarrassing) question. On one hand, the aliens are impressive enough to send craft here. On the other, they seem constrained by scarcity.

Are we humans like those bears filmed in the Richard Attenborough nature programs, worthy of periodic visits from drone cameras but otherwise of little interest? The reality is that bears, and indeed most other animals, see humans quite often…

3. The alien-origin hypothesis relies too much on the “argument from elimination.”

The argument from elimination is a common rhetorical tactic, but it can lead you astray. You start by listing what you think are all the possibilities and rule them out one by one: Not the Russians, not sensor error, and so on — until the only conclusion left is that they are alien visitors. As Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes once said: “When you have eliminated all which is impossible, then whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth.”

The argument from elimination works fine when there is a fixed set of possibilities, such as the murder suspects on a train. The argument is more dangerous when the menu of options is unclear in the first place. Proponents of the alien origin view spend too much time knocking down other hypotheses and not enough time making the case for the presence of aliens.

And this:

There is an argument that is often used against the alien-origin hypothesis, but in fact can be turned either way: If they are alien visitors, why don’t we have better and more definitive forms of evidence? Why is the available video evidence so hard to interpret? Why isn’t there a proverbial “smoking gun” of proof for an alien spacecraft?

This particular counter isn’t entirely convincing. First, the best evidence may be contained in the still-classified materials. Second, the same question can be used against non-alien hypotheses. If the sensor readings were just storms or some other mundane phenomena, surely that would become increasingly obvious over time with better satellite imaging.

The continued, ongoing and indeed intensifying mystery of the sightings seems to militate in favor of a truly unusual explanation. It will favor both the alien-visitation and the religious-miracle hypotheses. If it really were a flock of errant birds, combined with some sensor errors, we would know by now.

Recommended.

Wednesday assorted links

That is now, this was then, Taiwan edition

Words matter, in diplomacy and in law.

Last week President Bush was asked if the United States had an obligation to defend Taiwan if it was attacked by China. He replied, “Yes, we do, and the Chinese must understand that. Yes, I would.”

The interviewer asked, “With the full force of the American military?”

President Bush replied, “Whatever it took” to help Taiwan defend itself.

A few hours later, the president appeared to back off this startling new commitment, stressing that he would continue to abide by the “one China” policy followed by each of the past five administrations.

Where once the United States had a policy of “strategic ambiguity” — under which we reserved the right to use force to defend Taiwan but kept mum about the circumstances in which we might, or might not, intervene in a war across the Taiwan Strait — we now appear to have a policy of ambiguous strategic ambiguity. It is not an improvement.

Here is the full 2001 Wapo Op-Ed — can you guess who the author was? Hint: a prominent Senator at the time. Via tekl.

The Parent Trap–Review of Hilger

Nate Hilger has written a brave book. Almost everyone will find something to hate about The Parent Trap. Indeed, I hated parts of it. Yet Hilger is willing to say truths that are often not said and for that I would rather applaud than cancel.

Nate Hilger has written a brave book. Almost everyone will find something to hate about The Parent Trap. Indeed, I hated parts of it. Yet Hilger is willing to say truths that are often not said and for that I would rather applaud than cancel.

Hilger argues that the problems of poverty, pathology and inequality that bedevil the United States are not primarily due to poor schools, discrimination, or low incomes per se. The primary cause is parents: parents who are unable to teach their children the skills that are necessary to succeed in the modern world. Since parents can’t teach the necessary skills, Hilger calls for the state to take their place with a dramatic expansion of not just child care but collective parenting.

Let’s unpack some details. Begin with schooling. It’s very common to bemoan the state of schools in the “inner city” or to complain about “local financing” which supposedly guarantees that poor counties will have underfunded schools. All of this, however, is decades out-of-date.

A hundred years ago there really were massive public-school resource gaps by class and race. These days, however, state and federal spending play a larger role than local property tax revenue and distribute educational resources more progressively….In fact, when we include federal aid, 42 states spent more on poor school districts than on rich school districts in 2012. The same pattern holds between schools within districts

….The highest spending districts are large urban centers such as New York City, Boston and Baltimore. These cities spend large sums to educate rich and poor children alike. p. 10-11

Hilger is correct. No matter what you saw on The Wire, Baltimore spends more than sixteen thousand dollars per student, among the highest in the nation in large school districts and above average for the nation as a whole. Public schools are quite egalitarian in funding with any bias running towards more funding for poorer districts.

Schools, Hilger writes are “actually the smallest and most equalizing part of a much larger skill-building system.” The real problem, says Hilger, are parents.

But what about discrimination? When it comes to wage discrimination, Hilger is brutally honest:

If we compare individuals with similar cognitive test scores, Black college graduates earn higher wages than white college graduates. Studies that don’t control for test score differences but examine earnings gaps within specific professions—lawyers, physicians, nurses, engineers, scientists—tend to find Black workers earn zero to 10 percent less than white workers. These gaps could reflect discrimination, unmeasured skill differences, or other factors such as geography. In any case, such gaps are small compared to the 50 percent overall Black-white earnings gap and reinforce the idea that closing skills gaps would go a long way toward closing income gaps.

Hilger argues that racism does play an important role in explaining Black-white wage differentials but it’s the historical racism that made black parents less skilled and less able to pass on skills to their children. In the twentieth century, Asians, Hilger argues, were discriminated against in the United States at least much as Black Americans. But the Asians that came to the United States had high skills while the legacy of slavery meant that Black Americans began with low skills. Asians, therefore, were better able to overcome discrimination. The success of Nigerians and Jamaican immigrants in the United States also speaks to this point. (Long time readers may recall that in 2016 I dubbed Hilger’s paper on Asian Americans and Black Americans the Politically Incorrect Paper of the Year .)

Parental investment is surely important but Hilger overstates his case. He writes as if poorer parents have neither the abilities nor the time to teach their children while richer, better educated parents simply invest lots of hours and money imbuing their children with skills:

…the enormous variation in parents’ own academic skills has big implications for kids because we also demand that parents try to be tutors. During normal times, parents in America spend an average of six hours per week helping—or trying to help—their kids with school work. Six hours per week is more than K12 math and English teachers get with children…good tutoring by parents for six hours a week, every week, year after year of childhood could raise children’s future earnings by as much as $300,000.

The data on the effectiveness of SAT test-prep suggests that these efforts are not nearly so effective as Hilger argues. The parental investment story also doesn’t fit my experience. I didn’t spend six hours a week helping my kids with their homework. I doubt most parents do. I simply assumed my kids would do their work. I do recall that we signed my kids up for tutoring at Kumon, the Japanese math education center. My kids would complain bitterly when we took them for drill on the weekend. It was mostly filling out rote forms and my kids would hide or bury their drill sheets so we were always behind. Driving my kids to the Kumon center, monitoring them. and forcing them to do the work when they rebelled like longshoreman on work-to-rule was time consuming and it was ruining our weekends. I felt guilty, but after a while, my wife and I gave up. Today one of my sons is a civil engineer and the other is a math and economics major at UVA.

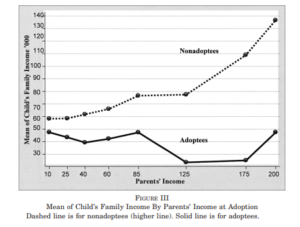

Hilger has an answer to this line of objection, or at least he says he does, but to my mind it’s a very odd answer. He argues, relying heavily on Sacerdote, that adoption studies show that more skilled parents result in more skilled kids. I find that answer odd because my reading of Sacerdote is that the effect of parents are small after you control for genetics—this is, as Hilger acknowledges, the conventional wisdom among psychologists. (See Caplan for an excellent review of the literature). It is true that Sacerdote plays up the effect of parents, but it looks small to me. Here is the effect of the adopted mother’s maternal education on the child’s education.

As you can see there is an effect but it is almost all from the mother going from having less than a high school education to graduating high school (11 to 12 years). In contrast, the mother can move from graduating high school to having a PhD and there is very little change in the education level of an adoptee. Note, however, that the effect on non-adoptees, i.e. biological children, is much larger throughout the entire range which suggests the influence of nature not nurture.

I am not surprised that there is some effect of parental education on child’s education because going to college is in part a cultural issue. Parents can influence cultural aspects of their children’s identity such as whether a child grows up up nominally Catholic, Mormon, or Hindu but they have relatively little effect on child religiosity, let alone personality or IQ. I think that a large fraction of the college wage premium is signaling (50% is a moderate estimate, Caplan thinks 90% is closer to the truth), so I am also not overly excited about college attendance as a marker of success.

The effect of parental income on the income of child adoptees is even more dramatic than on education—which is to say negligible. The income of the adopted parents has zero effect (!) on child’s income even as parent’s income varies by a factor of 20! The only correlation is with non-adoptee income—which again suggests the influence of nature not nurture.

At this point in the book, it was almost inevitable that we were going to get yet another paean to the Perry Preschool Project and indeed Hilger waxes enthusiastically about Perry. Seriously? The Perry Preschool project started in the 1960s and had just 123 participants (58 in treatment and 65 in control!). There are more papers about the Perry Preschool project than there were participants. I am jaded.

Aside from the small sample size, the project had imperfect randomization and missing data and most importantly limited external validity. The Perry Preschool project treated a small group of disadvantaged African American children with low-IQs (IQs of 70-85 were part of the selection criteria). The treatment is usually described as “active learning pre-school” but it was more intrusive than that. Every week counselors would go to the homes of the kids to teach the parents (mostly mothers) how to raise their children. The training was important to the program. Indeed, Hilger notes, without sense of irony, that “facilitating greater skill growth in low-income children was so complicated that it required home visitors with advanced postsecondary degrees.” (p. 89). And what were the results?

The results were good! (Heckman et al. 2010, Belfield et al. 2006). But in the popular literature the impression one gets is that the program took a bunch of disadvantaged kids and helped them read and write, making them more middle-class and successful. Some of that happened but the big gains actually happened because the participants, especially the boys, were so socially dangerous and destructive that even a bit of normalization made life substantially better for everyone else. In particular 82% of the treated group of 33 males had been arrested by age 40, including for one murder, 4 rapes, 8 robberies, 11 assaults and 14 burglaries. The control group were worse. In the control group of 39 males there were 2 murders. Indeed the reduction of one murder in the treatment group accounts for a significant benefit of the entire Perry PreSchool project.

Hilger, to his credit, is reasonably clear that what is really needed is an intensive program for disadvantaged African Americans, especially males. In a stunning sentence he writes:

The more we rely on families rather than professionals to build skills in children, the tighter we link people’s current prospects to the prospects of their ancestors. p. 134

But he soon forgets or papers over the context of the Perry Preschool project and like everyone else in the literature uses this to support a national program for which there is no external validity. It’s hard to believe, given the lack of external validity, but Heckman et al. (2010) only exagerate mildly when they write:

The economic case for expanding preschool education for disadvantaged children is largely based on evidence from the HighScope Perry Preschool Program…

Hilger’s case for the difficulty of parenting is well taken—the FAFSA was a nightmare that taxed two PhDs in my family. But the bottom line is that most parents do just fine. Moreover, it’s shocking that in recounting the difficulties of parenting Hilger says hardly one word about an obvious factor which makes parenting more than twice as hard. Namely, single parenting. I was a single parent. Once for a whole week. Don’t do it. Get married, stay married. Perhaps Hilger didn’t want to appear to be too conservative.

Instead of recommending marriage and small targeted programs and more experiments, Hilger goes full Plato.

What would it look like if we [asked]…less not more of parents? It would look like professional experts managing more than the meagre 10 percent of children’s time currently managed by our public K12 system—much more. p. 184

And why should we do this? Because we are all part slaves and part slave-owners on a giant collective farm:

As fellow citizens who benefit from tax revenue, we all—even those of us without children—collectively own about 30 percent of any additional income other people’s children wind up earning. p. 197

Ugh. We own ourselves, not one another. Society isn’t about maximizing the collective it’s about free individuals coming together to produce rules so that we can enjoy the benefits of collective action while still living in a diverse society that respects individual rights, beliefs, and ways of living.

I told you I hated parts of The Parent Trap but Hilger has written an interesting and challenging book and he is mostly right that neither schooling nor labor market discrimination play a major role in the black-white wage gap. Hilger is probably also right that we spend too much on the elderly relative to the young. The idea of greater state involvement in the raising of children is on the table today in a way it hasn’t been for some time. See also Dana Susskind’s recent book Parent Nation. Changes on the margin may be warranted. Nevertheless, I stand with Aristotle and not Plato in thinking that raising children is better done by parents than by the state.