Thursday assorted links

1. Nowrasteh and Bourne on DOGE.

2. “The paradox of India: Punjab is over 60% vegetarian, but Tandoori chicken and butter chicken are its most popular dishes outside the state. Tamil Nadu is less than 1% vegetarian, but its “pure veg” idly, dosa, sambhar, pongal, etc are its most popular dishes outside the state.” Link here.

3. Trump’s remarks on the Kennedy Center (NYT).

4. Helsinki architecture (NYT).

6. By decisive margins, Americans want Trump to adhere to court rulings.

Caleb Watney on risk and science funding

Right now, DOGE is treating efficiency as a simple cost-cutting exercise. But science isn’t a procurement process; it’s an investment portfolio. If a venture capital firm measured efficiency purely by how little money it spent, rather than by the returns it generated, it wouldn’t last long. We invest in scientific research because we want returns — in knowledge, in lifesaving drugs, in technological capability. Generating those returns sometimes requires spending money on things that don’t fit neatly into a single grant proposal.

While it’s true that indirect costs serve an important function, they can also create perverse incentives: When the government promises to cover expenses, expenses tend to go up. But instead of slashing funding indiscriminately, we should be thinking about how to get the most out of every dollar we invest in science.

That means streamlining research regulations. Universities are drowning in bureaucracy. Since 1990, there have been 270 new rules that complicate how we conduct research. Institutional Review Boards, intended to protect people from being unethically experimented on in studies, now regularly review low-risk social science surveys that pose no real ethical concerns. Researchers generate reams of paperwork in legally mandated disclosures of every foreign contract and collaboration, even for countries such as the Netherlands that present no geopolitical risk.

We must also rethink how we select scientific research to fund.

Caleb is co-CEO of the Institute for Progress, here is more from the NYT.

My excellent Conversation with Ezra Klein

Ezra is getting plenty of coverage for his very good and very on the mark new book with Derek Thompson, Abundance. So far it is a huge hit after only a few days. I figured this conversation would be most interesting, and add the most value, if I tried to push him further from a libertarian point of view (a sign of respect of course). Here is the audio, video, and transcript. Here is part of the episode summary:

In this conversation, Ezra and Tyler discuss how the abundance agenda interacts with political polarization, whether it’s is an elite-driven movement, where Ezra favors NIMBYism, the geographic distribution of US cities, an abundance-driven approach to health care, what to do about fertility decline, how the U.S. federal government might prepare for AGI, whether mass layoffs in government are justified, Ezra’s recommended travel destinations, and more.

Lots of good back and forth, here is one excerpt:

COWEN: Here’s a question from a reader, and I’m paraphrasing. “I can see why you would favor Obamacare and an abundance agenda because Obamacare throws a lot more resources at the healthcare sector in some ways. It did have Medicare cuts, but nonetheless, it’s not choking the sector. But if you favor an abundance agenda, can you then possibly favor single-payer health insurance through the government, which does tend to choke resources and stifle innovation?”

KLEIN: I think it would depend on how you did the single-payer healthcare. Here, we should talk about — because it’s referenced glancingly in the book in a place where you and I differ — but the supervillain view that I hold and your view, which is that you should negotiate drug prices. I’ve always thought on that because I think in some ways, it’s a better toy example than single payer versus Obamacare.

I think you want to take the amount of innovation you’re getting very, very, very seriously. I’ve written pieces about this, that I think if you’re going to do Medicare drug pricing at any kind of significant level, you want to be pairing that with a pretty significant agenda to make drug discovery much easier, to make testing much easier.

And:

COWEN: What should the US federal government do to prepare for AGI? We should just lay off people, right?

KLEIN: [laughs] I would not say it that way. I wouldn’t say just lay off people. I think that’s some of what we’re doing.

COWEN: No, not just, but step one.

KLEIN: Do you think that’s step one? Do you buy this DOGE’s preparation-for-AGI argument that you hear?

COWEN: I think maybe a fifth of them think that. Maybe it’s step two or step three, but it’s a pretty early step, right?

KLEIN: I think that the question of AI or AGI in the federal government, in anywhere — and this is one reason I’ve not bought this argument about DOGE — is you have to ask, “Well what is this AI or AGI doing? What is its value function? What prompt have you given it? What have you asked it to execute across the government and how?”

Alignment, which we have primarily talked about in terms of whether or not the AI, the superintelligence makes us all into paperclips, is a constant question of just near-term systems as well. I think the question of how should we prepare for AGI or for AI in the federal government first has to do with deciding what we would like the AI or the AGI to do. That could be different things to different areas.

My sense — talking to a bunch of people in the companies has helped me conceptualize this better — is that the first thing I would do is begin to ask, what do I think the opportunities of AI are, scientifically and in terms of different kinds of discoveries…

And this:

COWEN: Let me give you another right-wing view, and tell me what you think. The notion that the most important feature of state capacity is whether a state has enough of its citizens willing to fight and die for it. In that case, the United States, Israel, but a pretty small number of nations have high state capacity, and most of Western Europe really does not because they don’t have militaries that mean anything. Is that just the number one feature of abundance in state capacity?

Recommended, obviously.

The importance of the chronometer

The chronometer, one of the greatest inventions of the modern era, allowed for the first time for the precise measurement of longitude at sea. We examine the impact of this innovation on navigation and urbanization. Our identification strategy leverages the fact that the navigational benefits provided by the chronometer varied across different sea regions depending on the prevailing local weather conditions. Utilizing high-resolution data on climate, ship routes, and urbanization, we argue that the chronometer significantly altered transoceanic sailing routes. This, in turn, had profound effects on the expansion of the British Empire and the global distribution of cities and populations outside Europe.

That is from a newly published paper by Martina Miotto and Luigi Pascali. Via the excellent Kevin Lewis.

Wednesday assorted links

The New Geography of Labor Markets

We use matched employer-employee data to study where Americans live in relation to employer worksites. Mean distance from employee home to employer worksite rose from 15 miles in 2019 to 26 miles in 2023. Twelve percent of employees hired after March 2020 live at least fifty miles from their employers in 2023, triple the pre-pandemic share. Distance from employer rose more for persons in their 30s and 40s, in highly paid employees, and in Finance, Information, and Professional Services. Among persons who stay with the same employer from one year to the next, we find net migration to states with lower top tax rates and areas with cheaper housing. These migration patterns greatly intensify after the pandemic and are much stronger for high earners. Top tax rates fell 5.2 percentage points for high earners who stayed with the same employer but switched states in 2020. Finally, we show that employers treat distant employees as a more flexible margin of adjustment.

That is from a new NBER working paper by Mert Akan, et.al.

“Explain to me the blog Marginal Revolution, throwing in random German terms, and also weaving in the story of a circus clown.”

From DeepSeek:

**Marginal Revolution** – the *Wirtschaftswunder* (economic miracle) of blogs, where Tyler Cowen and Alex Tabarrok dissect the *Zeitgeist* (spirit of the age) through the lens of economics, culture, and *Hintergedanken* (ulterior motives). Founded in 2003, it’s a *Schnellimbiss* (fast-food joint) for ideas: bite-sized posts on everything from pandemic policy to why cilantro tastes like *Seife* (soap) to some people. Its ethos? *„Think globally, snack intellectually.“*

Now, meet **Klaus**, a *Zirkusclown* from Heidelberg whose *Clownswagen* (clown car) doubled as a mobile library of economic theory. While his peers mastered *Luftballontiere* (balloon animals), Klaus obsessed over *Anreize* (incentives) and *Knappheit* (scarcity). One night, after a *Desaster* of a show (audience: three bored *Kindergartenkinder*), he stumbled upon Marginal Revolution. *„Ach du lieber!“* he gasped. *„These Ökonomen understand comedy! Markets are just a *Tanz* (dance) of supply and demand!“*

Klaus’s *Erleuchtung* (epiphany)? Apply Cowen’s *„Tyler’s Law“* (*„Most of life is about signaling“*) to clowning. He ditched his rainbow wig for a *Bowlerhut* (bowler hat), rebranded as *„Herr Marginal,“* and crafted acts that mirrored economic principles:

– **The Tragedy of the Commons**: Juggle pies while a rival clown (*Doppelgänger* in a Tyler Cowen mask) “overgrazed” the audience’s laughter.

– **Creative Destruction**: Chainsaw his unicycle to build a *Schwebebalken* (balance beam) of innovation.

– **Schadenfreude Economics**: “Accidentally” squirt *Senf* (mustard) on wealthy patrons, testing if laughter correlates with income elasticity.

The *Zirkusdirektor* (ringmaster) fumed: *„Clowns sollen lustig sein, nicht klug!“* (Clowns should be funny, not smart!). But Klaus’s *Wissenschaft des Lachens* (science of laughter) drew crowds. His pièce de résistance? A *Pantomime* on **hyperinflation**, where he blew up a rubber *Hund* (dog) until it popped, showering the crowd with confetti *Geld* (money). *„Seht her!“* he cried. *„Gelddrucken ist wie Clownerie—zu viel, und es endet in *Chaos!“*

MargRev’s comment section erupted. Cowen himself tweeted: *„Klaus versteht die *Unsichtbare Hand* besser als manche Nobelpreisträger.“* (Klaus grasps the Invisible Hand better than some Nobel laureates.)

**Moral**: Marginal Revolution, like a *Zirkus*, thrives on *Überraschung* (surprise) and *Vielfalt* (diversity). Whether analyzing crypto or clowning, it’s all about the *Grenznutzen* (marginal utility) of ideas. And sometimes, the deepest truths wear red noses. *Prost mit Popcorn-Ökonomie!* 🎪🤡📉

*P.S.* Klaus’s next act? A *Game Theory* showdown: *„Das Gefangenendilemma mit Clowns—wer lacht zuerst, verliert.“* Spoiler: Everyone wins.

What do I think of the NIMBY contrarianism piece?

You know, the one from yesterday suggesting that tighter building restrictions have not led to higher real estate prices, at least not in the cross-sectional data? My sense is that it could be true, but we should not overestimate its import. In most circumstances, economists should focus on output, not prices per se. Let’s say we can build more homes, and prices for homes in that area do not fall. That can be a good thing! It is a sign that the homes are of high value, and people have the means to pay for them. It can be a sign that the higher residential density has not boosted crime rates, and so on. I find some of the more left-leaning YIMBY arguments are a bit too focused on distribution. I am happy if more YIMBY leads to a more egalitarian distribution of incomes, but I do not necessarily expect that. Often it leads to more agglomeration and higher wages, and high real estate prices too. The higher output and greater freedom of choice still are good outcomes.

Tuesday assorted links

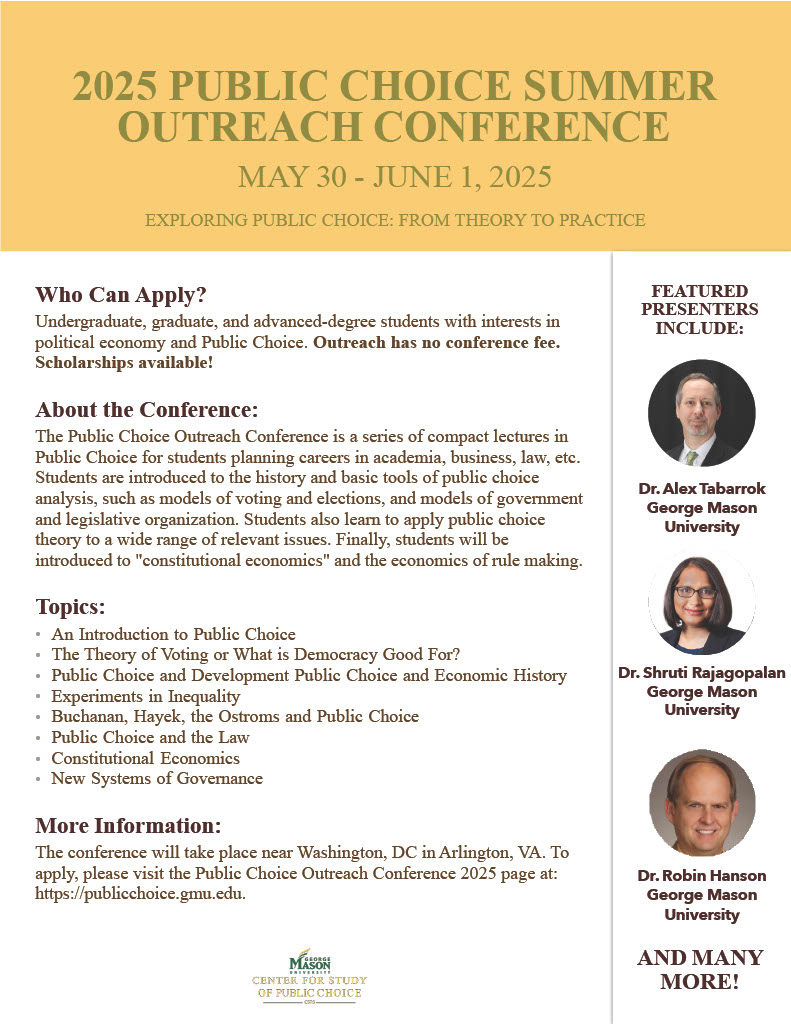

Public Choice Outreach Conference!

The annual Public Choice Outreach Conference is a crash course in public choice. The conference is designed for undergraduates and graduates in a wide variety of fields. It’s entirely free. Indeed scholarships are available! The conference will be held Friday May 30-Sunday June 1, 2025, near Washington, DC in Arlington, VA. Lots of great speakers. More details in the poster. Please encourage your students to apply.

The Anatomy of Marital Happiness

How can I not link to a new Sam Peltzman piece on such a topic? Here goes:

Since 1972, the General Social Survey has periodically asked whether people are happy with Yes, Maybe or No type answers. Here I use a net “happiness” measure, which is percentage Yes less percentage No with Maybe treated as zero. Average happiness is around +20 on this scale for all respondents from 1972 to the last pre-pandemic survey (2018). However, there is a wide gap of around 30 points between married and unmarried respondents. This “marital premium” is this paper’s subject. I describe how this premium varies across and within population groups. These include standard socio demographics (age, sex, race education, income) and more. I find little variety and thereby surface a notable regularity in US socio demography: there is a substantial marital premium for every group and subgroup I analyze, and this premium is usually close to the overall 30-point average. This holds not just for standard characteristics but also for those directly related to marriage like children and sex (and sex preference). I also find a “cohabitation premium”, but it is much smaller (10 points) than the marital premium. The analysis is mainly visual, and there is inevitably some interesting variety across seventeen figures, such as a 5-point increase in recent years.

Via the excellent, and married, Kevin Lewis.

The Institute for Museum and Library Services is going away

Last year the agency provided $266.7m in grants to libraries, museums and related institutions across the country and its territories. Those grants ranged widely in value and purpose, such as $343,521 to support an internship and fellowship programme at the Museo de Arte de Puerto Rico or $10,350 for the Art Museum of Eastern Idaho to develop new curricula for groups of visiting schoolchildren.

The Wilson Center at the Smithsonian will be gone, and:

The other agencies targeted for elimination in Trump’s executive order are the Federal Mediation and Conciliation Service, the United States Agency for Global Media (which operates the Voice of America media network), the United States Interagency Council on Homelessness, Community Development Financial Institutions Fund and the Minority Business Development Agency.

Here is the full story, I do not regard these as tragedies.

NIMBY contrarianism

The standard view of housing markets holds that the flexibility of local housing supply–shaped by factors like geography and regulation–strongly affects the response of house prices, house quantities and population to rising housing demand. However, from 2000 to 2020, we find that higher income growth predicts the same growth in house prices, housing quantity, and population regardless of a city’s estimated housing supply elasticity. We find the same pattern when we expand the sample to 1980 to 2020, use different elasticity measures, and when we instrument for local housing demand. Using a general demand-and-supply framework, we show that our findings imply that constrained housing supply is relatively unimportant in explaining differences in rising house prices among U.S. cities. These results challenge the prevailing view of local housing and labor markets and suggest that easing housing supply constraints may not yield the anticipated improvements in housing affordability.

That is from a new NBER working paper by Schuyler Louie, John A. Mondragon, and Johannes Wieland.

Monday assorted links

1. Does generative AI support the MAGA aesthetic style? (NYT)

2. Would you rather have married young?

3. Possible improvements in teen mental health?

4. LLMs produce funnier memes than the average human, though not as funny as the top humans.

5. On Becoming a Guinea Fowl is another good Zambian movie, here is the trailer.

What Did We Learn From Torturing Babies?

As late as the 1980s it was widely believed that babies do not feel pain. You might think that this was an absurd thing to believe given that babies cry and exhibit all the features of pain and pain avoidance. Yet, for much of the 19th and 20th centuries, the straightforward sensory evidence was dismissed as “pre-scientific” by the medical and scientific establishment. Babies were thought to be lower-evolved beings whose brains were not yet developed enough to feel pain, at least not in the way that older children and adults feel pain. Crying and pain avoidance were dismissed as simply reflexive. Indeed, babies were thought to be more like animals than reasoning beings and Descartes had told us that an animal’s cries were of no more import than the grinding of gears in a mechanical automata. There was very little evidence for this theory beyond some gesturing’s towards myelin sheathing. But anyone who doubted the theory was told that there was “no evidence” that babies feel pain (the conflation of no evidence with evidence of no effect).

Most disturbingly, the theory that babies don’t feel pain wasn’t just an error of science or philosophy—it shaped medical practice. It was routine for babies undergoing medical procedures to be medically paralyzed but not anesthetized. In one now infamous 1985 case an open heart operation was performed on a baby without any anesthesia (n.b. the link is hard reading). Parents were shocked when they discovered that this was standard practice. Publicity from the case and a key review paper in 1987 led the American Academy of Pediatrics to declare it unethical to operate on newborns without anesthesia.

In short, we tortured babies under the theory that they were not conscious of pain. What can we learn from this? One lesson is humility about consciousness. Consciousness and the capacity to suffer can exist in forms once assumed to be insensate. When assessing the consciousness of a newborn, an animal, or an intelligent machine, we should weigh observable and circumstantial evidence and not just abstract theory. If we must err, let us err on the side of compassion.

Claims that X cannot feel or think because Y should be met with skepticism—especially when X is screaming and telling you different. Theory may convince you that animals or AIs are not conscious but do you want to torture more babies? Be humble.

We should be especially humble when the beings in question are very different from ourselves. If we can be wrong about animals, if we can be wrong about other people, if we can be wrong about our own babies then we can be very wrong about AIs. The burden of proof should not fall on the suffering being to prove its pain; rather, the onus is on us to justify why we would ever withhold compassion.

Hat tip: Jim Ward for discussion.