The man who catalogues the Royal Family

Long before there was such a thing as “Big Data,” there was Tim O’Donovan, a retired insurance broker who has meticulously tabulated the British royal family’s engagements with pencil and paper every day for 40 years.

In a row of old-fashioned leather-bound ledgers, in a wisteria-fringed house in the village of Datchet, just west of London, he has amassed an extraordinary collection of raw data. The Autumn Dinner of the Fishmongers’ Company, convened in October by Princess Anne? It’s in there. The opening of the Pattern Weaving Shed in Peebles, Scotland? Of the Dumfries House Maze? Of a window at the Church of St. Martin in the Bull Ring? Noted.

Mr. O’Donovan, 87, is not part of the hurly-burly of royal commentary. Not only is he not active on social media, he claims never to have seen it. (“I am glad to say I don’t have anything to do with it,” he said, a bit starchily. “Everything I’ve heard about it is negative.”)

Every year, Mr. O’Donovan releases a comparative table listing the number of engagements attended by the highest-ranking royals, setting off a flurry of barbed commentary in the British news media. The feeding frenzy comes because Mr. O’Donovan, intentionally or not, has effectively invented a metric of how much the members of the royal family work.

He does it for fun, as his hobby:

Born into a family of avid collectors, he hungered in his 40s to undertake a statistical project; he had been impressed by a man who used public records to tabulate the waxing and waning popularity of baby names, publishing his findings once a year in a letter to the editor of The Times of London. He found his fodder in the Court Circular, an account of the royals’ engagements that appears in The Times of London. He decided to clip each one, paste it in a ledger and run the numbers, releasing his first results at the end of 1979.

Here is more from Ellen Barry (NYT). Here is an article on digital hoarders.

Saturday assorted links

Evidence for the Continental Axis Hypothesis

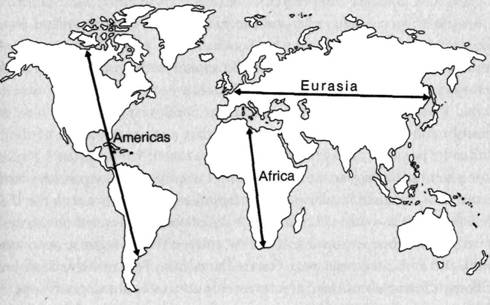

One of the most striking hypotheses in Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs, and Steel was that technology diffused more easily along lines of latitude than along lines of longitude because climate changed more rapidly along lines of longitude making it more difficult for both humans and technologies to adapt. Thus, a long East-West axis, such as that found in Eurasia, meant a bigger “market” for technology and thus greater development.

difficult for both humans and technologies to adapt. Thus, a long East-West axis, such as that found in Eurasia, meant a bigger “market” for technology and thus greater development.

A few pieces of evidence are suggestive:

Laitin and Robinson (2011) and Laitin et al. (2012) report that linguistic diversity has been historically more persistent across lines of latitude than longitude, suggesting that population movements were more prevalent East-West relative to North-South. Ramachandran and Rosenberg (2011) report similar evidence based on the geographic distribution of genetic variation. While these studies speak to greater movements of populations East-West relative to North-South, they do not speak directly to the diffusion of technologies and development. Alternatively, Olsson and Hibbs (2005) provide a cross-country analysis in which a variable measuring East-West orientation of major landmasses correlates significantly with present-day income levels. This finding explicitly links continental orientation to income levels. However, it does not speak directly to the mechanisms (e.g., more diffusion of technologies) leading to this correlation.

In Did Technology Transfer More Rapidly East-West than North-South?, from which I just quoted, Pavlik and Young offer more direct evidence on the natural direction of technological diffusion:

We employ Comin et al.’s (2010) data on ancient and early modern levels of technology adoption in a spatial econometric analysis. Historical levels of technology adoption in a (present-day) country are related to its lagged level as well as those of its neighbors. We allow the spatial effects to differ depending on whether they diffuse East-West or North-South. Consistent with the continental orientation hypothesis, East-West spatial effects are generally positive and stronger than those running North-South.

Very cool!

Damien Hirst markets in everything

The Palms Casino Resort in Las Vegas is taking the concept of luxe travel to a whole different level. Its new Damien-Hirst-designed Empathy Suite costs $100,000 a night.

The room is the most expensive in America, beating out one at The Mark hotel, which previously held the accolade at $75,000 a night. And Empathy is also one of the world’s most expensive hotel accommodations, according to The Palms. (In fact, it’s potentially the most expensive: The Royal Penthouse Suite at the President Wilson Hotel in Geneva — at about $80,000 a night — was the world’s most expensive suite in 2018, according to Lonely Planet.)

…The room was designed by world-renowned artist Hirst and showcases a number of his well-known original pieces, like the iconic “Winner/Loser,” with two bull sharks suspended in formaldehyde.

Hirst — who is known for controversial pieces — also created a 13-seat curved bar filled with medical waste, and hanging above the bar is Hirst’s “Here for a Good Time, Not a Long Time,” which features a marlin skeleton and taxidermy marlin.

Here is more text and photos, noting that perhaps the high price is in part “advertising” so that major gamblers feel good when the room is comped to them?

Those new service sector jobs is this one in fact torture?

Imagine: For the rest of your life, you are assigned no tasks at work. You can watch movies, read books, work on creative projects or just sleep. In fact, the only thing that you have to do is clock in and out every day. Since the position is permanent, you’ll never need to worry about getting another job again.

Starting in 2026, this will be one lucky (or extremely bored) worker’s everyday reality, thanks to a government-funded conceptual art project in Gothenburg, Sweden. The employee in question will report to Korsvägen, a train station under construction in the city, and will receive a salary of about $2,320 a month in U.S. dollars, plus annual wage increases, vacation time off and a pension for retirement. While the artists behind the project won’t be taking applications until 2025, when the station will be closer to opening, a draft of the help-wanted ad is already available online, as Atlas Obscura reported on Monday.

The job’s requirements couldn’t be simpler: An employee shows up to the train station each morning and punches the time clock. That, in turn, illuminates an extra bank of fluorescent lights over the platform, letting travelers and commuters know that the otherwise functionless employee is on the job. At the end of the day, the worker returns to clock out, and the lights go off. In between, they can do whatever they want, aside from work at another paying job.

That is by Antonia Noori Farzan at WaPo. The project is called “Eternal Employment.”

For the pointer I thank Peter Sperry.

China non-fact of the day

China’s economy is about 12 per cent smaller than official figures indicate, and its real growth has been overstated by about 2 percentage points annually in recent years, according to research. The findings in the paper published on Thursday by the Brookings Institution, a Washington think-tank, reinforced longstanding scepticism about Chinese official statistics. They also add to concerns that China’s slowdown is more severe than the government has acknowledged. Even based on official data, China’s economy grew at its slowest pace since 1990 last year at 6.6 per cent.

That is from Gabriel Wildau of the FT — adjust your debt to gdp ratios accordingly.

Friday assorted links

The Brother Earnings Penalty

This paper examines the impact of sibling gender on adolescent experiences and adult labor market outcomes for a recent cohort of U.S. women. We document an earnings penalty from the presence of a younger brother (relative to a younger sister), finding that a next-youngest brother reduces adult earnings by about 7 percent. Using rich data on parent-child interactions, parents’ expectations, disruptive behaviors, and adult outcomes, we provide a first step at examining the mechanisms behind this result. We find that brothers reduce parents’ expectations and school monitoring of female children while also increasing females’ propensity to engage in more traditionally feminine tasks. These factors help explain a portion of the labor market penalty from brothers.

That is by Angela Cooks and Eleonora Patacchin in Labour Economics. Once again, family niche effects seem to matter. Via the excellent Kevin Lewis.

Writers vs. entrepreneurs, publishers vs. venture capitalists

Henry Oliver asks:

In what ways are writers and entrepreneurs similar? Why doesn’t publishing have more of a VC structure and attitude? Could authorship be made more productive and better quality with VC in publishing and theatre? Are movies better at this?

Publishing has one feature in common with venture capital, namely that most financed undertakings are failures and the most profitable successes can be hard to predict in advance. Furthermore, publishers are always on the lookout for the soon-to-be-hot, hitherto unpublished author, the next Mark Zuckerberg so to speak. And books, like software and also successful social networks, are rapidly scalable. You can sell millions with a big hit. But here are a few differences:

1. A lot of VC is person-focused. The VC company builds a relationship with a young talent, and in some cases the hope is that the second or third business makes it, or that the person can be steered in the proper direction early on. Authors, in contrast, are more mobile across publishers, and the publisher usually is buying “a book” rather than “a relationship with the author.” Some wags would say that a publisher is buying a title, a cover, and the author’s social media presence.

2. Entrepreneurs commonly have more than one VC, but authors, for a single book, do not have multiple publishers.

3. For the vast majority of books which do not make a profit, this is evident within the first three weeks of release or perhaps before release altogether. The publisher may drop its resource commitment to the author very quickly, and even yank the PR people off the case. This further loosens the bond between the talent (the author) and the funders of the talent (the publisher). In contrast, VC rounds can last five or ten years, with commitments made in advance and possibly a board seat as part of the deal.

4. Venture capitalists will introduce their entrepreneurs to an entire network of supporting talent and connections. Publishers will edit and advise on a manuscript, but it is much more of an arm’s length relationship, and a publisher might do very little to bring an author into any kind of network.

5. The major publishing houses are clustered in Manhattan, just as the major venture capitalist firms are clustered in the Bay Area. But the publishers don’t find a pressing need to have their authors living in or near NYC, though for some other reasons that is convenient for the author doing eventual media appearances.

6. Publishers often care a great deal about an author’s preexisting platforms, such as Twitter followers or ability to get on NPR. Venture capitalists realize that a very good product can overcome the lack of initial renown. When Page and Brin started Google, they didn’t, believe it or not, have any Twitter followers at all. In fact, you couldn’t even Google them.

What else?

Ghent bleg

What to do and where to eat? I thank you all in advance for your wisdom and counsel.

Thursday assorted links

1. Why did hats fall out of fashion?

2. Vero on U.S. industrial policy (NYT).

3. Deepfakes are not yet such a problem.

5. Rolf Degen on “popular belief.” And asparagus.

Theranos was Fraudulent, What About Its Patents?

In Launching the Innovation Renaissance I argued that patents should be given for specific inventions rather than just for broad “ideas”:

Thomas Edison invented and patented numerous products: the light bulb, the phonograph, movie film and much else besides. (At one point the patent office required that patents be accompanied by working models.) The invention of products typically requires the expenditure of sunk costs in a way that the creation of ideas does not. Today it is not necessary to implement an idea to patent it, and many patentable ideas are so broadly phrased that they could not be implemented in a model.

Edison famously said that “genius is one percent inspiration, ninety-nine percent perspiration.” A patent system should reward the 99 percent perspiration, not the 1 percent inspiration. In inventing the light bulb, for example, Edison laboriously experimented with some 6,000 possible materials for the filament before hitting upon bamboo. If Edison were to patent the light bulb today, he would not need to go to such lengths. Instead, Edison could patent the use of an “electrical resistor for the production of electro-magnetic radiation,” a patent that would have covered oven elements as well as light bulbs.

, who holds the Mark Cuban Chair to Eliminate Stupid Patents at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, points out in an excellent article that giving patents for vaguely stated ideas was exactly the problem with Theranos and its so-called patents.

Holmes found a more receptive audience at the USPTO. She says she spent five straight days at her computer drafting a patent application. The provisional application, filed in September 2003 when Holmes was just 19 years old, describes “medical devices and methods capable of real-time detection of biological activity and the controlled and localized release of appropriate therapeutic agents.” This provisional application would mature into many issued patents. In fact, there are patent applications still being prosecuted that claim priority back to Holmes’ 2003 submission.

But Holmes’ 2003 application was not a “real” invention in any meaningful sense. We know that Theranos spent years and hundreds of millions of dollars trying to develop working diagnostic devices. The tabletop machines Theranos focused on were much less ambitious than Holmes’ original vision of a patch. Indeed, it’s fair to say that Holmes’ first patent application was little more than aspirational science fiction written by an eager undergraduate.

…Two legal doctrines are relevant here. The “utility” requirement of patent law requires that the invention work. And the “enablement” requirement means that the application has to describe the invention with enough detail to allow a person in the relevant field to build and use it. If the applicant herself can’t build the invention with nearly unlimited time and money, it does not seem like the enablement requirement could possibly be satisfied.

The USPTO generally does a terrible job of ensuring that applications meet the utility and enablement standards.

Despite never having built a working product, Theranos accumulated hundreds of patents. These patents are now the only thing of value left but the patents aren’t valuable because of breakthrough science, the patents are valuable because they can be used to force people who do breakthrough science to cough up part of their return.

As Nazer puts it:

Accused of having lied to investors and endangered patients, the company leaves us with a parting gift: a portfolio of landmines for any company that actually solves the problems Theranos failed to solve.

The real threats to free speech on campus

That is the topic of my latest Bloomberg column, here is an excerpt:

…being at a state school is hardly a guarantee of tolerance. Teaching at a state university does widen the scope of what a professor can say without being fired. But ongoing student protests or unfavorable treatment from colleagues can make continued employment so unpleasant that a person simply decides to leave. In my experience, most professors aren’t in it for the money — rather, they love their work. Loving your work is a gift that can be taken away rather easily, regardless of whatever formal legal protections there may be.

Or consider the position of a student. You might have the legal right to start a pro-Trump group on campus. But you might be dissuaded from doing so if you fear your professors would respond by writing you mediocre letters of recommendation.

What really matters on campus is what the most obstreperous participants in these debates consider to be acceptable behavior and speech, and how far they will take their protests. These individuals are usually those with relatively little to lose from strident behavior, and perhaps some local status to gain. They may be students, or they may not; they can be student counselors, or faculty members, or even low-level university bureaucrats.

I explain in the piece why my own university, George Mason, has been strong in this regard. And I am not crazy about the new proposed Trump executive order:

The relevant troublemakers are hardly ever university administrators. Yet they would inevitably become entangled in any tighter federal free-speech regulations. I have found such administrators to be pragmatic and able to see multiple sides of an issue, even if I do not always agree with their stances. Their primary goal is usually to get the rancor and protests to go away, so the business of the university can return to normal. Placing more constraints on their behavior could actually weaken their hand — by limiting their ability to mollify unruly student groups, for instance.

The full piece offers several additional arguments of note, so do read the whole thing. Here is my conclusion:

I’m all for free speech, whether for public or private schools. But the fight has to be won in the hearts and minds of students and workers, not by the federal government.

Work isn’t so bad

Although we spend much of our waking hours working, the emotional experience of work, versus non-work, remains unclear. While the large literature on work stress suggests that work generally is aversive, some seminal theory and findings portray working as salubrious and perhaps as an escape from home life. Here, we examine the subjective experience of work (versus non-work) by conducting a quantitative review of 59 primary studies that assessed affect on working days. Meta-analyses of within-day studies indicated that there was no difference in positive affect (PA) between work versus non-work domains. Negative affect (NA) was higher for work than non-work, although the magnitude of difference was small (i.e., .22 SD, an effect size comparable to that of the difference in NA between different leisure activities like watching TV versus playing board games). Moderator analyses revealed that PA was relatively higher at work and NA relatively lower when affect was measured using “real-time” measurement (e.g., Experience Sampling Methodology) versus measured using the Day Reconstruction Method (i.e., real-time reports reveal a more favorable view of work as compared to recall/DRM reports). Additional findings from moderator analyses included significant differences in main effect sizes as a function of the specific affect, and, for PA, as a function of the age of the sample and the time of day when the non-work measurements were taken. Results for the other possible moderators including job complexity and affect intensity were not statistically significant.

That is from a new paper by Martin J. Biskup, Seth Kaplan, Jill C. Bradley-Geist, and Ashley A. Membere. Such meta-analyses have their problems, but I consider other kinds of analysis, with complementary results, in my forthcoming book Big Business: A Love Letter to an American Anti-Hero.

Via Rolf Degen.

Hypnotist markets in everything

Those new service sector jobs:

This hypnotist charges half a bitcoin for helping you remember your lost cryptocurrency password…

“If you’ve got, you know, $100,000, $200,000, $300,000 worth of bitcoin in a wallet and you can’t get access to it, there’s a lot of stress there,” he says. “So it’s not just as simple as saying, okay, we’re going to go do a 30-minute hypnosis session and enhance your memory.”

Miller declined to specify the exact number of participants in his bitcoin password recovery program or how much money he’s recovered, citing client confidentiality. However, he says that there are currently “several people” in his program, who are experiencing varying degrees of success.

Generally, a person who created their password more recently will have an easier time unlocking this memory, he says. Likewise, a client who is feeling low stress will have an easier time remembering their password than one under high stress.

Miller is located in Greenville, South Carolina.

For the pointer I thank Nick Glenn.

Daniel Nazer

Daniel Nazer