Why (and How) Young People Should Go Into Debt to Buy Stocks

In 2022, I highlighted Ian Ayres and Barry Nalebuff’s proposal that young people should borrow to invest in the stock market. Why? Most people invest gradually, which leads to a concentration of stock holdings late in life. By borrowing early, young investors can spread market risk more evenly across their lifetime, much like diversifying across assets. Put differently, a young person’s biggest asset is their future labor income. Borrowing to invest reduces overexposure to that single asset, effectively diversifying their portfolio away from specific human capital and toward financial capital.

I supported the idea writing that “I agree with Ayres and Nalebuff that young people should be [at least] 100% in equities” but I didn’t expect people to go beyond this until the idea became standardized in a similar way to home mortgages. I wrote, “It could be standardized, however, with retirement planning products.”

Well, we now have our first product in this category, Basic Capital. Basic Capital is a mortgage for investing in stocks and bonds. You put in $1 and you get $5 of investment. Moreover, you cannot lose more than you put in. How is that possible? The investments are constrained–85% of it goes to bonds and 15% to equity but remember that 15% is on $5 rather than $1 so instead of investing $1 in stocks you are investing $.75 in stocks and $4.25 in bonds. The net result is broader exposure at lower individual risk. Whether it’s a compelling product depends on fees and execution, which seem high, but the underlying idea is innovative, and I’m excited to see how products in this new category evolve.

Addendum: Matt Levine offers further commentary. On the general topic of innovative financial products, see also my previous post on Shiller’s Macro Markets.

Hat tip: Naveen.

Manufacturing Went South

Excellent piece by Gary Winslett in the Washington Post. As I pointed out in my piece on Manufacturing and Trade, the US is a manufacturing powerhouse. So why did the rust belt rust? Because manufacturing went South.

The Rust Belt’s manufacturing decline isn’t primarily about jobs going to Mexico. It’s about jobs going to Alabama, South Carolina, Georgia and Tennessee…In 1970, the Rust Belt was responsible for nearly half of all manufacturing exports while the South produced less than a quarter. Today, the roles are reversed, it is the Rust Belt that hosts less than one-fourth of all manufactured exports and the South that exports twice what the Rust Belt does.

Why the move? Better policies:

Economic research suggests that labor conflict drove much of the decline of the Rust Belt. Right-to-work laws in the South, by contrast, created more operational flexibility and attracted capital. The average unionization rate in the Rust Belt is 13.3 percent; in the South, it’s 4.3 percent. Southern states’ political leaders are quite open about how they see right-to-work as foundational to their competitiveness.

But that’s far from the only factor. The South offers cheaper electricity, a critical input for energy-intensive manufacturing. Ten states in the South have industrial electricity rates under 8 cents per kilowatt-hour; zero states in the Rust Belt do. Ohio has some of the country’s most restrictive wind-energy setback regulations. You know who doesn’t? Texas.

Despite the economic growth, Southern states have built so much housing that they kept costs from becoming unaffordable. Last year, both North Carolina and South Carolina each built more than four times as much new housing per capita as Massachusetts, according to U.S. census data. Florida, Georgia, Texas, Tennessee, South Carolina and North Carolina, all built more housing per capita than all of Illinois, Ohio, Michigan, Pennsylvania, California, New York and Massachusetts. That is not just a 2024 dynamic. That is true for every single year going all the way back to 1993. Comparatively low-cost housing makes it easier to attract and retain workers, which further attracts capital, which adds yet more investment and jobs, and the virtuous cycle spins upward.

…Immigration helps a lot, as well. More immigrants live in the South than any other region of the country. The region with the fewest immigrants? The Midwest. Immigrants promote growth, makes the workforce more robust, and create the goods and services that support manufacturing.

Right-to-work laws, cheap energy, affordable housing, low-cost land, fast permitting, low taxes, immigration. That’s a powerful combination…

Neither party wants to face these realities. The Republicans are mired in victimology and don’t see that the South’s success is built on exporting and immigration, both of which they are cutting. The Democrats don’t want to acknowledge right to work laws, cheap energy and low taxes.

Both parties prefer simple villains, whether it’s China or greedy corporations. But what’s needed isn’t more warm fuzzies about the way things used to be or globalization scapegoating. It is a clear-eyed approach that understands why companies choose Alabama over Ohio and that embraces the choices made by Southern states. That means leaning into globalization, right-to-work, all-of-the-above energy policy, permitting reform, immigration and low taxes. America’s economic future depends on embracing this reality rather than in indulging in turn-back-the-clock fictions.

Glow in the Dark Flowers!

I love these glow-in-the-dark petunias. Aside from the novelty, they speak to science and progress! The petunias were genetically modified to incorporate genes from a bioluminescent mushroom.

Econ 101 is Underrated: Pharma Price Controls

Econ 101 is often dismissed as too simplistic. Yet recent events suggest that Econ 101 is underrated. Take the tariff debate: understanding that a tariff is a tax, that prices represent opportunity costs, that a bilateral trade deficit is largely meaningless, that a so-called trade “deficit” is equally a goods surplus or an investment surplus—these are Econ 101 ideas. Simple but important.

Today’s example is Trump’s Executive Order on pharmaceutical pricing. It builds on the Biden Administration’s Inflation Reduction Act, which I’ve criticized as failing the marshmallow test. Now Trump is trying to go further—threatening antitrust action and even drug delistings unless pharmaceutical firms equalize prices globally. Tyler and I explored exactly this type of policy in our Econ 101 textbook, Modern Principles of Economics.

In our chapter on price discrimination, we first show that pharmaceutical firms will want to charge different prices in different markets depending on the elasticity of demand. In order to do so, they must prevent arbitrage. Hence the opening to that chapter:

After months of investigation, police from Interpol swooped down on an international drug syndicate operating out of Antwerp, Belgium. The syndicate had been smuggling drugs from Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania into the port of Antwerp for distribution throughout Europe. Smuggling had netted the syndicate millions of dollars in profit. The drug being smuggled? Heroin? Cocaine? No, something more valuable: Combivir. Why was Combivir, the anti-AIDS drug we introduced in Chapter 13 , being illegally smuggled from Africa to Europe when Combivir was manufactured in Europe and could be bought there legally?

The answer is that Combivir was priced at $12.50 per pill in Europe and, much closer to cost, about 50 cents per pill in Africa. Smugglers who bought Combivir in Africa and sold it in Europe could make approximately $12 per pill, and they were smuggling millions of pills. But this raises another question. Why was GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) selling Combivir at a much lower price in Africa than in Europe? Remember from Chapter 13 that GSK owned the patent on Combivir and thus has some market power over pricing. In part, GSK reduced the price of Combivir in Africa for humanitarian reasons, but lowering prices in poor countries can also increase profit. In this chapter, we explain how a firm with market power can use price discrimination—selling the same product at different prices to different customers—to increase profit.

Later in the Thinking and Problem Solving section we ask:

As we saw in this chapter, drug companies often charge much more for the same drug in the United States than in other countries. Congress often considers passing laws to make it easier to import drugs from these low-price countries (it also considers passing laws to make it illegal to import these drugs, but that’s another story).

If one of these laws passes, and it becomes effortless to buy AIDS drugs from Africa or antibiotics from Latin America—drugs that are made by the same companies and have essentially the same quality controls as the drugs here in the United States—how will drug companies change the prices they charge in Latin America and Africa? Why?

That, in essence, is the Trump policy. So what’s the likely outcome? Prices will fall in the U.S. and rise in poorer countries—but not equally. AIDS drugs, for example, save lives in Africa but generate little profit. If firms can’t prevent arbitrage, they’ll raise African prices closer to U.S. levels and lower U.S. prices only modestly.

The result is that importation will end up hurting patients in low-income countries while delivering minimal gains to Americans. Worse, by reducing pharmaceutical profits overall, it weakens incentives to develop new drugs. In fact, in the long-run U.S. consumers are better off when poorer countries pay lower prices—just as airline price discrimination makes more routes viable for both economy and first-class passengers.

The reference pricing envisaged in Trump’s EO focuses on developed countries but Dubois, Gandhi and Vasserman run the numbers in a fully-specified model and reach similar conclusions:

Using our estimates of consumer preferences, marginal costs, and bargaining parameters, we assess the impact of a counterfactual in which US pharmaceutical prices are subject to international reference pricing with respect to Canada or an average of several similar countries….Our results suggest that international reference pricing on its own is unlikely to produce dramatic savings to US consumers. Overall, reference pricing induces a substantial increase in the prices charged in reference countries but only a modest decrease in the prices charged in the US.

It’s also the case that countries that pay less for pharmaceuticals get them later than countries that pay more. Most importantly, such launch delays (and here) tend to reduce life expectancy.

Thus, Econ 101 provides a critical foundation for understanding current debates.

Beyond Econ 101, it’s worth highlighting how internally inconsistent Trump’s policies are. At the same time, as the administration is raising tariffs worldwide, it wants to greatly reduce restrictions on importing pharmaceuticals! The most charitable interpretation (steel-manning) is that the ultimate goal of the Trump approach is to boost industry profits and incentivize R&D by raising prices in other countries. But it’s hard to square that with reducing prices here. Either the investment is worth it or not. Instead of focusing on investment or efficiency, Trump frames everything as grievance and redistribution: other countries are “ripping us off,” so they must be made to pay. But the pie shrinks when you fixate on dividing it instead of growing it. Moreover, Trump’s belligerent approach is unlikely to succeed because, as with tariffs, it invites retaliation. Instead, we should be pursuing IP protections for pharmaceuticals as part of an overall free trade agreement. We did precisely this, for example, in the Australia–United States Free Trade Agreement (AUSFTA) in 2005. That type of bilateralism and negotiation is anathema to Trump, however, who sees the world in zero-sum terms. As a result, the Biden-Trump policies are likely to lead future Americans to have less access to life-saving and life-improving pharmaceuticals.

Addendum: See also many previous MR posts on pharmaceutical regulation including The US has Low Prices for Most Pharmaceuticals, Pharmaceutical Price Controls and the Marshmallow Test, Update on the supervillains and Frank Lichtenberg and the cost of saving lives through pharmaceuticals as well as many others.

Adam Smith on Mercantilism

ChatGPT: Adam Smith strongly criticized mercantilism in The Wealth of Nations (1776), arguing that it was a flawed and self-defeating economic doctrine. His main points:

-

Wealth is not gold: Mercantilists equated national wealth with the accumulation of gold and silver (bullion). Smith rejected this, emphasizing instead that real wealth lies in a nation’s productive capacity—its ability to produce goods and services.

-

Trade is not zero-sum: Mercantilists saw international trade as a zero-sum game where one nation’s gain is another’s loss. Smith argued trade is mutually beneficial. He introduced the idea of absolute advantage, showing how specialization and exchange increase the wealth of all nations.

-

Protectionism hurts consumers: Mercantilist policies favored domestic producers through tariffs and trade restrictions. Smith viewed these as harmful to consumers, who are forced to pay higher prices and have fewer choices. He famously wrote:

“Consumption is the sole end and purpose of all production; and the interest of the producer ought to be attended to, only so far as it may be necessary for promoting that of the consumer.”

-

Cronyism and rent-seeking: Smith accused mercantilist policies of serving powerful interest groups (e.g., guilds, monopolies, chartered trading companies) at the expense of the public. He viewed the system as corrupted by lobbying and state favoritism:

“The interest of the dealers… in any particular branch of trade or manufactures, is always in some respects different from, and even opposite to, that of the public.”

-

Free trade promotes growth: Smith advocated for a liberal trade regime based on natural liberty. He saw the division of labor and free exchange as key drivers of economic growth and prosperity.

In short, Smith saw mercantilism as a doctrine that enriched special interests and weakened overall prosperity. He called for a shift toward a system where markets and competition—not state-backed monopolies—allocate resources efficiently.

Is MR Biased?

Long Time MR reader Sean R. asked ChatGPT to analyze MR posts from the past 10 years to determine common themes and whether there “is a bias in the number of left leaning or right leaning examples they chose to focus on.” Here’s ChatGPT’s answer (with some editing for length):

How I approached the question (30-second summary)

|

Step

|

What I actually did

|

|---|---|

|

1 – Define the stance

|

For each of the ten recurring Marginal Revolution (MR) themes (inflation, housing, AI, immigration, trade, inequality, growth, pandemic policy, regulation/state-capacity, education) I wrote down MR’s normative position—e.g. “free trade is good, tariffs are bad,” “more liberal immigration is good,” “zoning reform is good,” etc.

|

|

2 – Collect posts (2016 → May 2025)

|

Searched the MR archive (site:marginalrevolution.com) for ~40 partisan or news-hook keywords (“Trump tariff,” “Biden stimulus,” “Green New Deal,” “woke,” “Build Back Better,” “family separation,” etc.). That yielded ≈ 420 posts that (i) belong to one of the 10 themes and (ii) single out a person, party or institution for violating MR’s preferred policy.

|

|

3 – Code each post

|

Manually read the headline + opening paragraph (or known MR shorthand) and coded:

• Theme (1-10) • Target (Right-leaning, Left-leaning, Both/Neutral) • Tone (Critical, Supportive, Mixed). Only “Critical” posts counted toward the bias score. |

|

4 – Cross-check with news cycle

|

For each quarter I ran a quick Factiva/Google News query (“tariff hike,” “student-loan forgiveness,” etc.) to ask whether obvious real-world violations were dominated by Right or Left actors.

|

Result 2 – Break-down by theme

|

Theme (MR stance)

|

Typical “Right-wing violation” called out

|

Typical “Left-wing violation” called out

|

Right-critical : Left-critical ratio

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Trade (pro-free-trade)

|

Trump/EU tariff wars, U.S. steel 232 duties Marginal REVOLUTION

|

Biden’s EV subsidy protectionism, Buy-American rules

|

28 : 13

|

|

Immigration (more open)

|

Family-separation, Muslim ban, Title 42 extension Marginal REVOLUTIONMarginal REVOLUTION

|

Blue-state NIMBY union restrictions, slow refugee processing (2022-23)

|

31 : 9

|

|

Housing/Zoning (YIMBY)

|

Suburban GOP blocking up-zoning in TX/FL

|

CA, MA, NYC progressive NIMBYism (“Berkeley slows dorms”)

|

10 : 17

|

|

Inflation & Fiscal

|

Trump 2018 tax cuts “stimulus at full employment”

|

Biden ARP, student-loan relief inflation risk Marginal REVOLUTIONMarginal REVOLUTION

|

13 : 21

|

|

Inequality/Redistribution

|

GOP SALT deduction push, regressive payroll holidays

|

Warren wealth-tax, $15 federal minimum wage

|

8 : 19

|

|

Regulation/State-capacity

|

Trump FDA/CDC staffing cuts, tariff waivers chaos

|

OSHA vaccine mandate over-reach, CA energy rules

|

12 : 14

|

|

AI & Growth

|

Trump chip-export bans framed as tech‐industrial policy

|

Biden CHIPS Act subsidy design flaws

|

6 : 7

|

|

Pandemic policy

|

Trump under-react 2020, “bleach,” CDC interference

|

Blue-state school closures 2021-22, eviction moratoria extensions

|

14 : 18

|

|

Education

|

DeSantis “Stop WOKE” limits on speech

|

Campus DEI mandates, student-loan forgiveness

|

10 : 24

|

|

Great-Stagnation/Growth

|

GOP ethanol & Jones Act protectionism

|

Dem climate permitting delays (NEPA)

|

46 : 15

|

Result 3 – Context vs. actual news “violations”

Cross-checking 140 weeks (2016-2025) of major economic headlines:

|

Period

|

Real-world violations skew

|

MR critical coverage skew

|

Alignment?

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

2017-20 (Trump years)

|

Mostly Right (tariffs, family-separation, payroll tax holiday)

|

MR posts ≈ 63% critical of Right

|

✔ tracks news

|

|

2021-23 (early Biden)

|

More Left (ARP cost, student-debt, OSHA mandates)

|

MR posts ≈ 56% critical of Left

|

✔ tracks news

|

|

2024-25 YTD

|

Mixed: Trump tariff talk + Biden industrial policy

|

MR split 48 : 46 (Right : Left)

|

✔ balanced

|

🧷 Bottom line

- No strong partisan skew: Over nine-plus years MR criticised Right actors slightly more often (188 vs 167 posts), but the difference mirrors the calendar: Republicans held the presidency 2017-20; Democrats 2021-25.

- Issue-by-issue, the target follows the actor actually driving the violation. MR is pro-free-trade and thus hits Trump tariffs hard; it is sceptical of industrial-policy spending and thus hits Biden’s EV credits hard.

- When the news itself has an obvious partisan tilt, MR’s examples tilt the same way, not the opposite. The blog appears issue-consistent rather than partisan-consistent.

Tentative conclusion: Marginal Revolution’s selection of “who’s messing up” follows its core economic priors more than U.S. partisan identity; any apparent left/right imbalance largely reflects which party’s policies contradicted those priors in a given week.

This is Vindication???

Joe Nocera has a strange piece in the Free Press arguing that the “godfathers of protectionism” have been vindicated. It begins with a story about how Dani Rodrik couldn’t get a famous economist to endorse his book Has Globalization Gone Too Far? because doing so would arm the barbarians. Well give that reluctant economist a Nobel! because they were obviously correct. Tyler made the same point in his debate with Rodrik. Rodrik had no answer.

The piece is strange because there is little to no connection with any data; just assertion, vibe, and non-sequitur. Most bizarrely but hardly alone was this bit:

In the 1980s, Prestowitz was an official in Ronald Reagan’s Commerce Department, back when Japan, not China, was the trading partner the U.S. most feared. Japanese autos, televisions, washing machines, and all sorts of consumer electronics were flooding into the U.S., forcing American auto makers to close factories and even putting U.S. companies like Zenith out of business. Yet Japan was using tariffs and other less obvious trade barriers to prevent U.S. companies from exporting many of their products to Japan. It was protecting certain key industries from foreign competition.

This was not how the rules of free trade were supposed to work. Prying that market open, forcing Japan to play by the same rules as the U.S., was Prestowitz’s job.

He found it deeply frustrating. “Every time we completed a trade negotiation,” Prestowitz told me, “some economist would turn out a model to show that the deal was going to create X number of American jobs and would reduce the trade deficit by Y. And it never happened.”

Even more galling, he said, “The conventional response among economists was that it didn’t matter.” After all, even if Japan was keeping U.S. products out of its market, America still benefited from low-cost imports. Prestowitz has a vivid memory of a conversation he once had with Herbert Stein, President Richard Nixon’s former chief economist. “The Japanese will sell us cars,” Stein told him with a shrug, “and we’ll sell them poetry.”

Prestowitz also remembers the abuse he took for his views. “I was a Japan-basher, a protectionist, and so on,” he said. Paul Krugman, who was not yet a New York Times columnist but was already an influential economist, called Prestowitz “an intellectual snake-oil salesman” in a book he wrote called Pop Internationalism. The book, published in 1997, consisted of a half-dozen essays, each of which brutally attacked one or another of the handful of people who dared to say that globalization was less than perfect. (He described then-Labor Secretary Robert Reich as “not a serious thinker,” and Lester Thurow, the best-selling author and Massachusetts Institute of Technology economist, as “silly.”)

When I asked Prestowitz recently if he felt vindicated, he admitted that he did, but added that “I also feel a sense of loss that it took us so long to face reality and at such cost.”

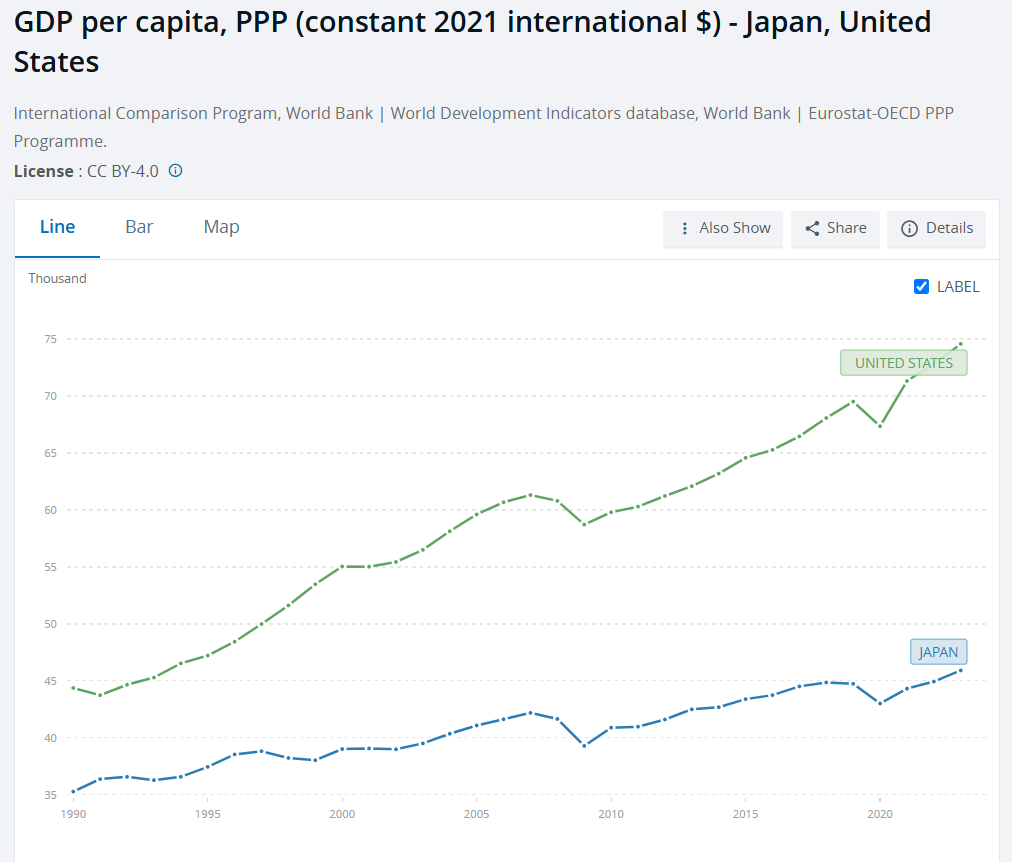

Well here is data on GDP per capita in real terms in Japan and the United States since 1990. This is vindication???!

Or how about this:

No one anymore, on the left or the right, denies that globalization has fractured the U.S., both economically and socially. It has hollowed out once-prosperous regions like the furniture-making areas of North Carolina and the auto manufacturing towns of the Midwest.

Well the far left and the far right agree that America has become fractured and hollowed out, the Bernie Sanders-Donald Trump horseshoe. But both are wrong. For the rest of us in the happy middle, consider this–Hickory, North Carolina, once known as the furniture capital of the United States, did face some hard times. But in 2023 Travel and Leisure magazine named Hickory the most beautiful and affordable place to live in the United States! Writing:

Located in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains, Hickory is a family-friendly destination known for its ample hiking trails and Southern charm. Currently ranked as the cheapest place to live in the U.S., Hickory has a median home price of $161,000. This affordable neighbor to the east of Asheville and north of Charlotte is popular with retirees, but it’s also becoming more attractive to young families; a steady stream of residents has been flocking here for its newfound fame as a technological hub for Google and Apple.

Doesn’t sound hollowed out to me.

The godfathers of protectionism haven’t been vindicated—but if they want to claim credit for President Trump’s tariff binge they’re welcome to it.

Addendum: Hat tip to Scott Lincicome on Hickory and do read Jeremy Horpedahl for details on the distribution of wages. Did you know, for example, that median weekly earnings for full time workers who graduated high school but are without a college degree are at an all time high? Switched earlier current for constant $2021 dollars in graph.

Has Clothing Declined in Quality?

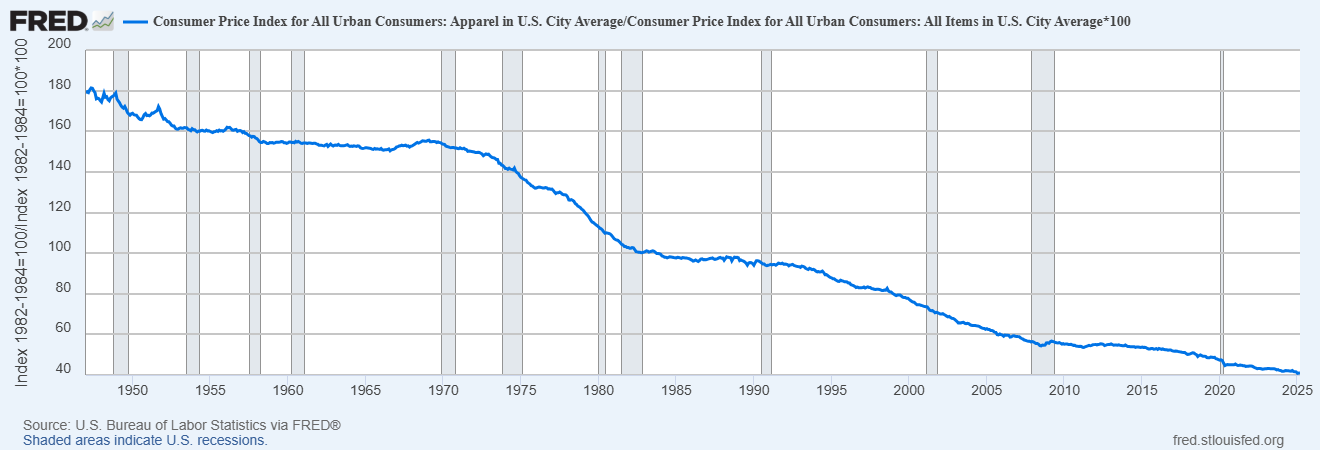

The Office of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) recently tweeted that they wanted to bring back apparel manufacturing to the United States. Why would anyone want more jobs with long hours and low pay, whether historically in the US or currently in places like Bangladesh? Thanks in part to international trade, the real price of clothing has fallen dramatically (see figure below). Clothing expenditure dropped from 9-10% of household budgets in the 1960s (down from 14% in 1900) to about 3% today.

Apparently, however, not everyone agrees. While some responses to my tweet revealed misunderstandings of basic economics, one interesting counter-claim emerged–the low price of imported clothing has been a false bargain, the argument goes, because the quality of clothing has fallen.

The idea that clothing has fallen in quality is very common (although it’s worth noting that this complaint was also made more than 50 years ago, suggesting a nostalgia bias, like the fact that the kids today are always going to hell). But are there reliable statistics documenting a decline in quality? In some cases, there are! For example, jeans from the 1960s-80s, for example, were often 13–16 oz denim, compared to 9–11 oz today. According to some sources, the average garment life is down modestly. The statistical evidence is not great but the anecdotes are widespread and I shall accept them. Most sources date the decline in quality to the fast fashion trend which took off in the 1990s and that provides a clue to what is really going on.

Fast fashion, led by firms like Zara, is a business model that focuses on rapidly transforming street style and runway trends into mass-produced, low-cost clothing—sometimes from runway to store within weeks. The model is not about timeless style but about synchronized consumption: aligning production with ephemeral cultural signals, i.e. to be fashionable, which is to say to be on trend, au-courant and of the moment.

It doesn’t make sense to criticize fast fashion for lacking durability—by design, it isn’t meant to last. Making it durable would actually be wasteful. The product isn’t just clothing; it’s fashionable clothing. And in that sense, quality has improved: fast fashion is better than ever at delivering what’s current. Critics who lament declining quality miss the point—it’s fun to buy new clothes and if consumers want to buy new clothes it doesn’t make sense to produce long lasting clothes. People do own many more pieces of clothing today than in the past but the flow is the fun.

So my argument is that the decline in “quality” clothing has little to do with the shift to importing but instead is consumer-driven and better understood as an increase in the quality of fashion. Testing my theory isn’t hard. Consider clothing where function, not just fashion, is paramount: performance sportswear and Personal Protective Equipment (PPE).

There has been a massive and obvious improvement in functional clothing. The latest GoreTex jackets, for example, are more than five times as water resistant (28 000 mm hydrostatic head) compared to the best waxed cotton technology of the past (~5 000 mm) and they are breathable (!) and lighter. Or consider PolarTec winter jackets, originally developed for the military these jackets have the incredible property of releasing heat when you are active but holding it in when you are inactive. (In the past, mountain climbers and workers in extreme environments had to strip on or off layers to prevent over-heating or freezing while exerting effort or resting.) Amazing new super shoes can actually help runners to run faster! Now that is high quality. Personal protective equipment has also increased in quality dramatically. Industrial workers and intense sports enthusiasts can now wear impact resistant gloves which use non-Newtonian polymers that stiffen on impact to reduce hand injuries.

Moreover, it’s not just functional clothing that has increased in quality. For those willing to look, there is in fact plenty of high-quality clothing readily available. From Iron Heart, for example, you can buy jeans made with 21oz selvedge indigo denim produced in Japan. Pair with a high-quality Ralph Lauren shirt, a Mackinaw Wool Cruiser Jacket and a nice pair of Alden boots. Experts like the excellent Derek Guy regularly highlight such high-quality options. Of course, when Derek Guy discusses clothes like this people complain about the price and accuse him of being an elitist snob. Sigh. Tradeoffs are everywhere.

Moreover, it’s not just functional clothing that has increased in quality. For those willing to look, there is in fact plenty of high-quality clothing readily available. From Iron Heart, for example, you can buy jeans made with 21oz selvedge indigo denim produced in Japan. Pair with a high-quality Ralph Lauren shirt, a Mackinaw Wool Cruiser Jacket and a nice pair of Alden boots. Experts like the excellent Derek Guy regularly highlight such high-quality options. Of course, when Derek Guy discusses clothes like this people complain about the price and accuse him of being an elitist snob. Sigh. Tradeoffs are everywhere.

Critics long for a past when goods were cheap, high quality, and Made in America—but that era never really existed. Clothing in the past was more expensive and often low quality. To the extent that some products in the past were of higher quality–heavier fabric jeans, for example–that was often because the producers of the time couldn’t produce it less expensively. Technology and trade have increased variety along many dimensions, including quality. As with fast fashion, lower quality on some dimensions can often produce a superior product. And, of course, it should be obvious but it needs saying: products made abroad can be just as good—or better—than those made domestically. Where something is made tells you little about how well it’s made.

The bottom line is that international trade has brought us more options and if today’s household were to redirect the historical 9 – 10 % share of income to clothing, it could absolutely buy garments that are heavier, better-constructed, and longer-lived than the typical mid-century mass-market clothing.

Tabarrok on the Movie Tariff

The Hollywood Reporter has a good piece on Trump’s proposed movie tariffs:

Even if such a tariff were legal — and there is some debate about whether Trump has the authority to impose such levies — industry experts are baffled as to how, in practice, a “movie tariff” would work.

“What exactly does he want to put a tariff on: A film’s production budget, the level of foreign tax incentive, its ticket receipts in the U.S.?” asks David Garrett of international film sales group Mister Smith Entertainment.

Details, as so often with Trump, are vague. What precisely constitutes a “foreign” production is unclear. Does a production need to be majority shot outside America — Warner Bros’ A Minecraft Movie, say, which filmed in New Zealand and Canada, or Paramount’s Gladiator II, shot in Morocco, Malta and the U.K. — to qualify as “foreign” under the tariffs, or is it enough to have some foreign locations? Marvel Studios’ Thunderbolts*, for example, had some location shooting in Malaysia but did the bulk of its production in the U.S, in Atlanta, New York and Utah.

…“The only certainty right now is uncertainty,” notes Martin Moszkowicz, a producer for German mini-major Constantin, whose credits including Monster Hunter and Resident Evil: The Final Chapter. “That’s not good for business.”

A movie producer is quoted on the bottom line:

“Consistent with everything Trump does and says, this is an erratic, ill conceived and poorly considered action,” says Nicholas Tabarrok of Darius Films, a production house with offices in Los Angeles and Toronto. “It will adversely affect everyone. U.S. studios, distributors, and filmmakers will suffer as much as international ones. Trump just doesn’t seem to understand that international trade is good for both parties and tariffs not only penalize international companies but also raise prices for U.S. based companies and consumers. This is an ‘everyone loses, no one gains’ policy.”

Lady Liberty of the Pacific

Instead of re-opening Alcatraz as super-max prison we should build a statue to America. I suggest “Lady Liberty of the Pacific”. The spirit of Columbia ala John Gast’s American Progress carrying a welcoming beacon-lamp in her raised right hand and a coiled fibre-optic cable in her left representing Bay Area technology.

Not De Minimis

Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick:

Ending the “de minimis loophole” is a big deal. This rule allowed foreign companies to avoid paying tariffs on small shipments, giving them an unfair advantage over American small businesses. To small businesses across the country: we have your back.

The Value of De Minimis Imports by Fajgelbaum and Khandelwal:

A U.S. consumer can import $800 worth of goods per day free of tariffs and administrative fees. Fueled by rising direct-to-consumer trade, these “de minimis” shipments have exploded in recent years, yet are not recorded in Census trade data. Who benefits from this type of trade, and what are the policy implications? We analyze international shipment data, including de minimis shipments, from three global carriers and U.S. Customs and Border Protection. Lower-income zip codes are more likely to import de minimis shipments, particularly from China, which suggests that the tariff and administrative fee incidence in direct-to-consumer trade disproportionately benefits the poor. Theoretically, imposing tariffs above a threshold leads to terms-of-trade gains through bunching, even in a setting with complete pass-through of linear tariffs. Empirically, bunching pins down the demand elasticity for direct shipments. Eliminating §321 would reduce aggregate welfare by $10.9-$13.0 billion and disproportionately hurt lower-income and minority consumers.

In other words, eliminating the de minimis rule is a significant tax on poorer Americans.

Frankly, it’s also a pain in the ass to have your international shipments delayed at broker (who often charges you exorbitant rates, more than the customs tax) and then have to go down to the customs office to pay the stupid tax. Yes, I am speaking from experience.

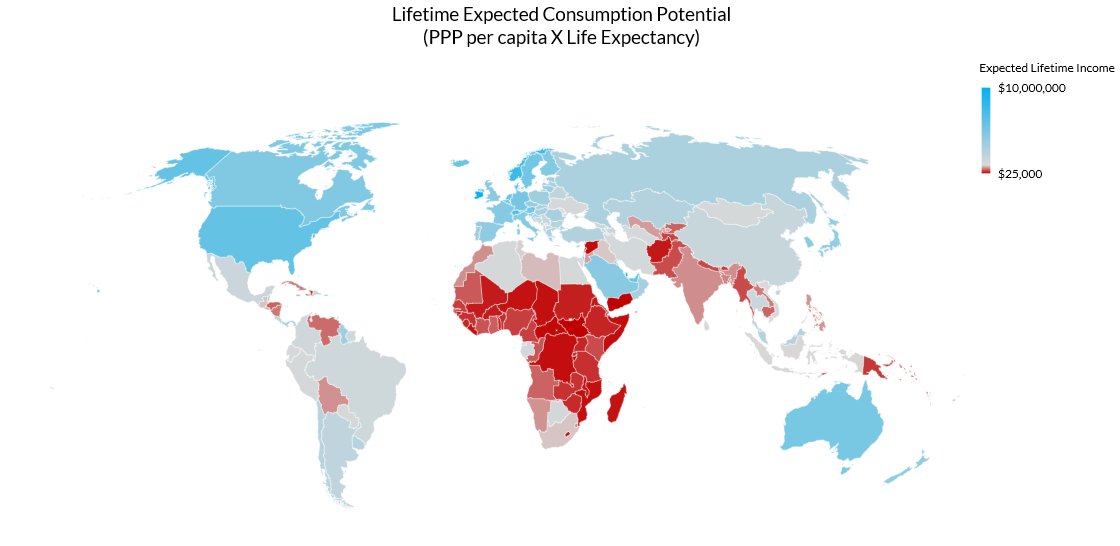

Lifetime Expected Consumption

What does it mean to be wealthy and how should we factor in say, life expectancy? Lyman Stone offers an interesting measure, lifetime consumption, taking in account (roughly) both years lived and how much one consumes in those years.

Tabarrok on the Not My Generation Podcast

Political Scientists James Davenport and Craig Dawkins interview me on everything from tariffs to the Borda Count. Here is one bit I wish to underline:

Q. In your opinion, what is the biggest economic myth or misconception that is holding the U.S. back?

What worries me most is that we’re treating China like an enemy—and that mindset risks becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy. What I want people to understand is this: we have a lot to gain from a rich China.

In my 2009 TED Talk, I gave one of my favorite examples. As China grows wealthier, it invests more in thinking—research, science, and development—that benefits the entire world. Richer countries face diseases of aging, not poverty. As China shifts its focus to diseases like cancer, it ramps up investment in drug development. That raises the odds of a cure—something worth trillions to humanity. If an American cured cancer, I’d be thrilled. If a Chinese citizen cured cancer, I’d be 99.9% as thrilled.

Yes, China is not a democracy. But by global standards, it hasn’t been especially militaristic. There have been border disputes, but no major invasions in over 50 years. China isn’t sending troops to the Middle East or Latin America.

That could change. But nothing inescapable says the U.S. and China must be enemies. We have far more to gain from peace, trade, and prosperity than from conflict.

What Should Classical Liberals Do?

My little contretemps with Chris Rufo raises the issue of what should classical liberals do? In a powerful essay, C. Bradley Thompson explains why the issue must be faced:

The truth of the matter is that the Conservative-Libertarian-Classical Liberal Establishment gave away and lost an entire generation of young people because they refused to defend them or to take up the issues that mattered most to them, and in doing so the Establishment lost America’s young people to the rising Reactionary or Dissident Right, by which I primarily mean groups such as the so-called TradCaths or Catholic Integralists and the followers of the Bronze Age Pervert. (See my essay on the reactionary Right, “The Pajama-Boy Nietzscheans.”)

I do not think Mr. Rufo would disagree with me on this point, but he has not quite made it himself either (at least not as far as I know), so I will make it in my own name.

The betrayal, abandonment, desertion, and loss of America’s young people by conservative and libertarian Establishmentarians can be understood with the following hypothetical.

Imagine the plight of, let us say, a 23-year-old young man in the year 2016. Imagine that he’s been told every single day from kindergarten through the end of college that he’s racist, sexist, and homophobic by virtue of being white, male, and heterosexual. Further imagine that he was falsely diagnosed by his teachers in grade school with ADD/ADHD and put on Ritalin because, well, he’s an active boy. And then his teachers tell him when he’s 12 that he might not actually be a boy, but rather that he might be a girl trapped in boy’s body. And let us also not forget that he’s also been told by his teachers and professors that the country his parents taught him to love was actually founded in sin and is therefore evil. To top it all off: he didn’t get into the college and then the law school of his choice despite having test scores well above those who did.

In other words, what this oppressed and depressed young man has experienced his whole life is a cultural Zeitgeist defined by postmodern nihilism and egalitarianism. These are the forces that are ruining his life and making him miserable.

Let’s also assume that said young man is also temperamentally some kind of conservative, libertarian, or classical liberal, and he interns at the Heritage Foundation, the Cato Institute, or the Institute for Humane Studies hoping to find solace, allies, and support to give relief to his existential maladies.

And how does Conservatism-Libertarianism Inc. respond to what are clearly the dominant cultural issues of our time?

Well, the Establishment publishes yet another white paper on free-market transportation or energy policy. The Heritage Foundation doubles down on more white papers on deficits and taxation policy. The Cato Institute churns out more white papers on legalizing pot and same-sex marriage. The Institute for Humane Studies goes all in to sit at the cool kids’ lunch table by ramping up its videos on spontaneous order featuring transgender 20-somethings.

Is it any wonder that today’s young people who have suffered the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune are stepping outside the arc of history yelling, “stop”? At a certain point, these young people let out a collective primal scream, shouting “I’m mad as hell and I’m not going to take it anymore.” And when the “youf” (as they refer to themselves online) realized that Establishment conservatives and libertarians did not hear them and lacked the vocabulary, principles, power, and courage to defend them from their Maoist persecutors, they went underground to places like 4chan, 8chan, and various other online discussion boards, where they found a Samizdat community of the oppressed.

Having effectively abandoned late-stage Millennials and Gen Z, Conservatism and Libertarianism Inc. should not be surprised, then, that today’s young people who might be otherwise sympathetic to their policies have left that world and become radicalized. News flash: Gen Z is attracted to people who are willing to defend them and attack social nihilism and egalitarianism in all their forms.

Hence the rise of what I call the “Fight Club Right,” which calls for a new kind of American politics. Gen Z rightism is done with what they call the Boomer’s “fake and ghey” attachment to the principles of the Declaration of Independence and the institutions of the Constitution. In fact, many young people who have migrated to the reactionary Right have openly and repeatedly rejected the principles of the American founding as irrelevant in the modern world.

More to the point, this younger generation is done with the philosophy of losing. They’re certainly done with the Establishment. They also seem to be done with classical liberalism and the American founding. (This is a more complicated topic.) Instead, what they want is political power to punish their enemies and to take over the “regime.” They want to use the coercive force of the State to create their new America.

…Conservatism and Libertarianism Inc. seemed utterly oblivious to the fact that the Left had pivoted and changed tactics after the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989. By the 1990s, the Left had abandoned economic issues and the working class and was doubling down on cultural issues. Rather than trying to take over the trade-union movement, for instance, the postmodern Left went for MTV and the Boy Scouts, while the major DC think tanks on the Right went for issues too distant from the lives of young people such as the deficit, taxation, and regulatory policy.

While socialism continues to be the end of the Left, the means to the end is postmodern nihilism. That’s where the Left planted its flag and that’s the terrain that it has occupied without opposition, whereas conservative and libertarian organizations such as the Heritage Foundation and the Cato Institute were fighting for ideological hegemony in the economic realm. Between 2000 and 2025, cultural nihilism and its many forms and manifestations is where the action is and has been for a quarter century. So powerful has postmodern nihilism become that even some left-wing “libertarian” organizations have simply become left-wing.

The Public Choice Outreach Conference

There are just a few spots left for the Public Choice Outreach Conference! Do encourage your students to apply!