Category: Economics

What should I ask John Arnold?

Yes, I will be doing a Conversation with him. John might be the smartest person I know about the energy sector and also about philanthropy. Here is the opening of his Wikipedia entry:

John Douglas Arnold (born 1974) is an American philanthropist, former Enron executive, and founder of Arnold Ventures LLC, formerly the Laura and John Arnold Foundation. In 2007, Arnold became the youngest billionaire in the U.S. His firm, Centaurus Advisors, LLC, was a Houston-based hedge fund specializing in trading energy products that closed in 2012. He now focuses on philanthropy through Arnold Ventures LLC. Arnold is a board member of Breakthrough Energy Ventures and since February 2024, is a member of the board of directors of Meta.

So what should I ask him?

Markets expand to fill empty spaces

How does a start-up founder hire a software engineer or a tech worker find a date in 2025? They could share a job posting on LinkedIn, log on to a dating app — or leave a handwritten note in a Waymo.

“Looking to hire senior software engineers to work on AI/music project,” said the note, a retro touch in a futuristic setting, with the company’s website and Angelini’s email scrawled below. That same day, another Waymo rider snapped a photo of the note and posted it on the social media platform X, where it has been reshared nearly 200 times, received more than 4,000 likes and more than 300,000 views…

A few days later, another handwritten ad found in a Waymo was shared on X from a single man looking for a date. The bachelor described himself as a 26-year-old who works in tech but “doesn’t make it my whole personality” and left a phone number for interested parties to text. The post has gotten more than 200 replies.

Problems in Treasury markets (from my email)

Max writes to me:

“Hope you’re doing well. And the craziness in the world hasn’t been affecting you too much. I know I’ve written to you about cash-treasury basis a couple of times over the years. The situation has unfortunately become somewhat more acute and has started to get wider media attention.

There are some good accounts of the issue in the media, by Matt Levine for example But, there are a few things being missed even in high quality media accounts:

- The issue is now a global one, which has not been the case historically. German bunds now trade at a negative swap spread (the yield on cash bonds is higher than on similar tenor swaps). This is a fairly recent development. It suggests the problem has shifted from being primarily a shortage of USD cash (though that is still true to a significant degree), to a global oversupply of longer dated bonds.

- A crunch in repo funding does not seem to be primarily responsible here. Balance sheet efficient methods of intermediating repo (sponsored repo) are more available now than they have been in the past. And they haven’t solved the problem.

- Permitting bond basis to fluctuate is quite pernicious. It meaningfully reduces the negative correlation between long bonds and risk assets. Meaningully reducing the attractiveness of holding them in a portfolio and increasing funding costs.

- At this point, global government debt outstanding is so large basis is so high that failing to correct this issue has a meaningful budget impact. Not only in the US, but across the Western world.

I think there is a straightforward solution: The Fed has clear cut authority to trade Treasury forwards during open market operations. Which would alleviate the pressure on dealer balance sheets, relieve market dysfunction, and help restore basis to more natural levels. And do so without relying on emergency authorities.”

America’s Tourism Deficit: How the French Are Winning the Currency War One Croissant at a Time

Every year, American tourists pour billions of dollars into France, wandering the Louvre, sipping overpriced espresso in Montmartre, and snapping selfies along the Seine—while far fewer French tourists bother making the reverse pilgrimage to admire, say, Disney World. The result? A massive tourism deficit.

On paper, this reflects wealth differentials and revealed preferences – Americans, being richer and more numerous than the French, express a high demand for old world Parisian experiences. But behind this innocent wanderlust is something more sinister. When Americans vacation in France, that’s counted as a US import of tourism. When French people vacation here—fewer, more begrudgingly—that’s a US export. So voilà, the tourism deficit creates a trade deficit, an excess of imports over exports!

The tourism deficit means there is a steady leak of the world’s reserve currency into the hands of a nation famous for its cheese, wine, and suspicion of American capitalism. France, using little more than museums and moodiness, is accumulating dollars from innocent American travelers. And they’re not just hoarding them for kicks. Those dollars are claims on real assets. First it’s a Napa vineyard. Then a Brooklyn fintech startup. Eventually, who knows? The Port of Long Beach? The Federal Reserve’s snack bar?

Make no mistake: France’s true comparative advantage isn’t wine or luxury goods—it’s the ruthless extraction of tourism dollars, performed with flawless precision, a disdainful shrug, and a little help from Emily in Paris. We’re being out-traded, one overpriced pastry at a time, by a nation whose strategic horizon spans centuries—and whose Netflix marketing is impeccable.

The political implications are, shall we say, obvious.

From now on, we demand a tourism balance. No more visa waivers, no more jet-setting to Provence until they send an equal number of French tourists to Branson, Missouri. It’s high time the French get over their Napoleon complex and start to appreciate American corn dogs and Dolly Parton. France needs to treat us with the same respect as the friendly countries that enthusiastically dispatch high-spending tourists to our shores.

It’s one-for-one, or the deal is off. Tourism parity or rien! Point final.

AI on Tariffs

There is some evidence that the White House used AI to come up with a quick and dirty (and incorrect) formula to correlate tariff rates with trade deficits. I have no problem with using AI, I think they just didn’t go far enough. The White House should have asked the AI a question like this:

Suppose the US imposed tariffs on other countries in an effort to reduce bilateral trade deficits to zero using the formula for the tariff of (exports-imports)/imports. What do you estimate would be the consequences of such a policy?

Answer (O1 Pro):

A tariff schedule keyed to bilateral deficits—imposing a rate equal to (US exports − US imports) / US imports—would be extremely disruptive and unlikely to achieve its goal. Key points:

Immediate Impact on Prices and Supply Chains

If the US imports more than it exports from a given country, (exports − imports) is negative, making the tariff percentage negative unless the formula is modified (e.g., by absolute value). In practice, one would presumably set a positive tariff aimed at closing the bilateral gap.

Such high tariffs would sharply raise import prices for both consumers and firms reliant on foreign inputs. It would encourage attempts to switch suppliers but at the cost of disrupting supply chains and increasing production expenses.

Retaliation and Trade War Dynamics

Targeted countries would almost certainly retaliate with their own tariffs. Retaliation would damage US export sectors—especially agriculture and high-value manufacturing—and risk a broader trade war.

Countries with a US trade surplus would apply punitive measures that shift US business to alternative suppliers, undermining the very exports the policy is meant to foster.

Misalignment with Macroeconomic Fundamentals

Bilateral imbalances reflect global production patterns, comparative advantage, and macro factors like savings–investment imbalances and currency flows. A country that persistently imports more overall does so because it’s running a capital account surplus. Tariffs don’t fundamentally alter that global saving–investment arithmetic.

If the US still runs an overall current account deficit, restricting imports from some countries will simply shift deficits to others. Global supply chains will rearrange, but the total US deficit will be largely unchanged.

Violation of Trade Agreements

Such a policy almost certainly violates WTO rules, since it imposes discriminatory tariffs based on bilateral imbalances. The resulting litigation and sanctions would add more uncertainty.

Net Effect: Reduced Efficiency, Higher Costs

Economically, the net effect is negative. Costs rise for US consumers and US manufacturers reliant on imported inputs. Retaliatory measures reduce export opportunities. Overall trade volume shrinks. Growth slows, and no fundamental improvement in the US external balance occurs.

In summary, a bilateral “deficit-equalizing” tariff policy would create severe distortions, invite retaliation, and do little to fix the structural causes of US trade deficits. Empirical evidence and standard trade theory both suggest it would reduce economic efficiency and likely harm US producers and consumers alike.

Good answer.

Hat tip: SB.

A Blueprint for FDA Reform

The new FDA report from Joe Lonsdale and team is impressive. It has a lot of new material, is rich in specifics and bold in vision. Here are just a few of the recommendation which caught my eye:

From the prosaic: GMP is not necessary if you are not manufacturing:

In the U.S., anyone running a clinical trial must manufacture their product under full Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP) regardless of stage. This adds enormous cost (often $10M+) and more importantly, as much as a year’s delay to early-stage research. Beyond the cost and time, these requirements are outright irrational: for example, the FDA often requires three months of stability testing for a drug patients will receive after two weeks. Why do we care if it’s stable after we’ve already administered it? Or take AAV manufacturing—the FDA requires both a potency assay and an infectivity assay, even though potency necessarily reflects infectivity.

This change would not be unprecedented either. By contrast, countries like Australia and China permit Phase 1 trials with non-GMP drug with no evidence of increased patient harm.

The FDA carved out a limited exemption to this requirement in 2008, but its hands are tied by statute from taking further steps. Congress must act to fully exempt Phase 1 trials from statutory GMP. GMP has its place in commercial-scale production. But patients with six months to live shouldn’t be denied access to a potentially lifesaving therapy because it wasn’t made in a facility that meets commercial packaging standards.

Design data flows for AIs:

With modern AI and digital infrastructure, trials should be designed for machine-readable outputs that flow directly to FDA systems, allowing regulators to review data as it accumulates without breaking blinding. No more waiting nine months for report writing or twelve months for post-trial review. The FDA should create standard data formats (akin to GAAP in finance) and waive documentation requirements for data it already ingests. In parallel, the agency should partner with a top AI company to train an LLM on historical submissions, triaging reviewer workload so human attention is focused only where the model flags concern. The goal is simple: get to “yes” or “no” within weeks, not years.

Publish all results:

Clinical trials for drugs that are negative are frequently left unpublished. This is a problem because it slows progress and wastes resources. When negative results aren’t published, companies duplicate failed efforts, investors misallocate capital, and scientists miss opportunities to refine hypotheses. Publishing all trial outcomes — positive or negative—creates a shared base of knowledge that makes drug development faster, cheaper, and more rational. Silence benefits no one except underperforming sponsors; transparency accelerates innovation.

The FDA already has the authority to do so under section 801 of the FDAAA, but failed to adopt a more expansive rule in the past when it created clinicaltrials.gov. Every trial on clincaltrials.gov should have a publication associated with it that is accessible to the public, to benefit from the sacrifices inherent in a patient participating in a clinical trial.

To the visionary:

We need multiple competing approval frameworks within HHS and/or FDA. Agencies like the VA, Medicare, Medicaid, or the Indian Health Service should be empowered to greenlight therapies for their unique populations. Just as the DoD uses elite Special Operations teams to pioneer new capabilities, HHS should create high-agency “SWAT teams” that experiment with novel approval models, monitor outcomes in real time using consumer tech like wearables and remote diagnostics, and publish findings transparently. Let the best frameworks rise through internal competition—not by decree, but by results.

…Clinical trials like the RECOVERY trial and manufacturing efforts like Operation Warp Speed were what actually moved the needle during COVID. That’s what must be institutionalized. Similarly, we need to pay manufacturers to compete in rapidly scaling new facilities for drugs already in shortage today. This capacity can then be flexibly retooled during a crisis.

Right now, there’s zero incentive to rapidly build new drug or device manufacturing plants because FDA reviews move far too slowly. Yet, when crisis strikes, America must pivot instantly—scaling production to hundreds of millions of doses or thousands of devices within weeks, not months or years. To build this capability at home, the Administration and FDA should launch competitive programs that reward manufacturers for rapidly scaling flexible factories—similar to the competitive, market-driven strategies pioneered in defense by the DIU. Speed, flexibility, and scale should be the benchmarks for success, not bureaucratic checklists. While the drugs selected for these competitive efforts shouldn’t be hypothetical—focus on medicines facing shortages right now. This ensures every dollar invested delivers immediate value, eliminating waste and strengthening our readiness for future crises.

To prepare for the next emergency, we need to practice now. That means running fast, focused clinical trials on today’s pressing questions—like the use of GLP-1s in non-obese patients—not just to generate insight, but to build the infrastructure and muscle memory for speed.

Read the whole thing.

Hat tip: Carl Close.

Britain’s productivity problem

A big chunk of it is coming from the health care sector. Information and communications are not growing in productivity as rapidly as before, and Britain has done less well boosting productivity with tech and also in oil and gas extraction. Here is the thread, here is the underlying study from the Resolution Foundation. This is important work.

A contagion of uncertainty

That is my latest piece for The Free Press, here is one excerpt:

It is not merely that the policies keep on changing. We are seeing that the policies didn’t have much of a rational basis to begin with. Exactly how were all those threatened tariff rates calculated to begin with? A debate is raging across the internet and social media, but it seems they did not have much of a logical basis. We even were ready to put a tariff rate of 10 percent on the Heard Island and McDonald Islands (where?), which are inhabited mostly by penguins.

Not a single step of this process has inspired confidence. A variety of people are trying to defend the Trump plans on social media, but with markets plummeting they have not been convincing. We saw a three-day market loss of about 13 percent, and no coherent government response.

Who in the Trump administration has presented any account of its policies to the public with any degree of knowledge, competence, or credible reassurance? What I have seen is Secretary of Commerce Howard Lutnick speaking about the new jobs Americans might have assembling iPhones, something which currently would most likely be done in a Chinese factory. Who is supposed to be thrilled by that vision of the American future? Or should we be reassured by the possibility that Lutnick did not mean that remark literally, but instead was speaking out of mere carelessness?

One lesson I am learning — yet again — is just how many people will defend a status quo backed by power…

Manufacturing and Trade

It has become popular in some circles to argue that trade—or, in the more “sophisticated” version, that the dollar’s reserve-currency status—undermines U.S. manufacturing. In reality, there is little support for this claim.

Let’s begin with some simple but often overlooked points.

- The US is a manufacturing powerhouse. We produce $2.5 trillion of value-added in manufacturing output, more than ever before in history.

- As a share of total employment, employment in manufacturing is on a long-term, slow, secular trend down. This is true not just in the United States but in most of the world and is primarily a reflection of automation allowing us to produce more with less. Even China has topped out on manufacturing employment.

- A substantial majority of US imports are for intermediate goods like capital goods, industrial supplies and raw materials that are used to produce other goods including manufacturing exports! Tariffs, therefore, often make it more costly to manufacture domestically.

- The US is a big country and we consume a lot of our own manufacturing output. We do export and import substantial amounts, but trade is not first order when it comes to manufacturing. Regardless of your tariff theories, to increase manufacturing output we need to increase US manufacturing productivity by improving infrastructure, reducing the cost of energy, improving education, reducing regulation and speeding permitting. You can’t build in America if you can’t build power plants, roads and seaports.

- The US is the highest income large country in the world. It’s hard to see how we have been ripped off by trade. China is much poorer than the United States.

- China produces more manufacturing output than the United States, most of which it consumes domestically. China has more than 4 times the population of the United States. Of course, they produce more! India will produce more than the United States in the future as well. Get used to it. You know what they say about people with big shoes? They have big feet. Countries with big populations. They produce a lot. More Americans would solve this “problem.”

- Most economists agree that there are some special cases for subsidizing and protecting a domestic industry, e.g. military production, vaccines.

The seven points cover most of the ground but more recently there has been an argument that the US dollar’s status as a reserve currency, which we used to call the “exorbitant privilege,” is now somehow a nefarious burden. This strikes me as largely an ex-post rationalization for misguided policies, but let’s examine the core claim: the US’s status as a reserve currency forces the US dollar to appreciate which makes our exports less competitive on world markets. Tariffs are supposed to (somehow?) depreciate the currency solving this problem. Every step is questionable. Note, for example, that tariffs tend to appreciate the dollar since the supply of dollars declines. Note also that if even if tariffs depreciated the currency, depreciating the currency doesn’t help to increase exports if you have cut imports (see Three Simple Principles of Trade Policy). I want to focus, however, on the first point does the US status as world reserve currency appreciate the dollar and hurt exports? This is mostly standard economics so its not entirely wrong but I think it misses key points even for most economists.

Countries hold dollars to facilitate world trade, and this benefits the United States. By “selling” dollars—which we can produce at minimal cost (albeit it does help that we spend on the military to keep the sea lanes open)—we acquire real goods and services in exchange, realizing an “exorbitant privilege.” Does that privilege impose a hidden cost on our manufacturing sector? Not really.

In the short run, increased global demand for dollars can push up the exchange rate, making exports more expensive. Yet this effect arises whatever the cause of the increased demand for dollars. If foreigners want to buy more US tractors this appreciates the dollar and makes it more expensive for foreigners to buy US computers. Is our tractor industry a nefarious burden on our computer industry? I don’t think so but more importantly, this is a short-run effect. Exchange rates adjust first, but other prices follow, with purchasing power parity (PPP) tendencies limiting any long-term overvaluation.

To see why, imagine a global single-currency world (e.g., a gold standard or a stablecoin pegged to the US dollar). In this scenario, increased demand for US assets would primarily lead to lower US interest rates or higher US asset prices, equilibrating the market without altering the relative price of US goods through the exchange rate mechanism. With freely floating exchange rates, the exchange rate moves first and the effect of the increased demand is moderated and spread widely but as other prices adjust the long-run equilibrium is the same as in a world with one currency. There’s no permanent “extra” appreciation that would systematically erode manufacturing competitiveness. Notice also that the moderating effect of floating exchange rates works in both directions so when there is deprecation the initial effect is spread more widely giving industries time to adjust as we move to the final equilibrium.

None of this to deny that some industries may feel short-run pressure from currency swings but these pressures are not different from all of the ordinary ups and down of market demand and supply, some of which, as I hove noted, floating exchange rates tend to moderate.

Ensuring a robust manufacturing sector depends on sound domestic policies, innovation, and workforce development, rather than trying to devalue the currency or curtail trade. Far from being a nefarious cost, the U.S. role as issuer of the world’s reserve currency confers significant financial and economic advantages that, in the long run, do not meaningfully erode the nation’s manufacturing base.

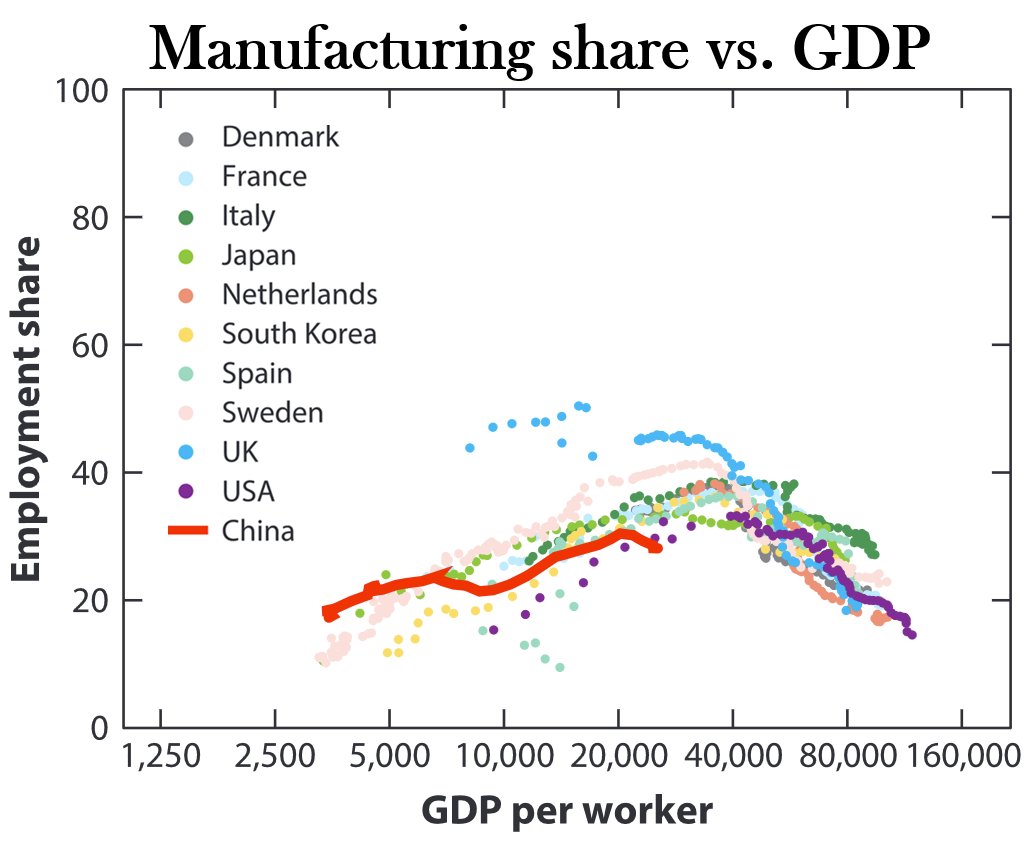

Manufacturing share vs. GDP

Via Basil Halperin. This is not a question of confusing causation and correlation, if anything it is the protectionists who have such an error in their mind’s eye. These days the average U.S. service sector job pays more than a manufacturing job.

Tariff sentences to ponder

We find that only 15.1 percent of the decline in goods-sector employment from 1992 to 2012 stems from U.S. trade deficits; most of the decline is due to differential productivity growth.

Here is the full paper by Kehoe, Ruhl, and Steinberg, via Zack Mazlish. I believe we have covered this issue before.

Why Do Domestic Prices Rise With Tarriffs?

Many people think they understand why domestic prices rise with tariffs–domestic producers take advantage of reduced competition to jack up prices and increase their profits. The explanation seems cynical and sophisticated and its not entirely wrong but it misses deeper truths. Moreover, this “explanation” makes people think that an appropriate response to domestic firms raising prices is price controls and threats, which would make things worse. In fact, tariffs will increase domestic prices even in perfectly competitive industries. Let’s see why.

Suppose we tax imports of French and Italian wine. As a result, demand for California wine rises, and producers in Napa and Sonoma expand production to meet it. Here’s the key point: Expanding production without increasing costs is difficult, especially so for any big expansion in normal times.

To produce more, wine producers in Napa and Sonoma need more land. But the most productive, cost-effective land is already in use. Expansion forces producers onto less suitable land—land that’s either less productive for wine or more valuable for other purposes. Wine production competes with the production of olive oil, dairy and artisanal cheeses, heirloom vegetables, livestock, housing, tourism, and even geothermal energy (in Sonoma). Thus, as wine production expands, costs increases because opportunity costs increase. As wine production expands the price we pay is less production of other goods and services.

Thus, the fundamental reason domestic prices rise with tariffs is that expanding production must displace other high-value uses. The higher money cost reflects the opportunity cost—the value of the goods society forgoes, like olive oil and cheese, to produce more wine.

And the fundamental reason why trade is beneficial is that foreign producers are willing to send us wine in exchange for fewer resources than we would need to produce the wine ourselves. Put differently, we have two options: produce more wine domestically by diverting resources from olive oil and cheese, or produce more olive oil and cheese and trade some of it for foreign wine. The latter makes us wealthier when foreign producers have lower costs.

Tariffs reverse this logic. By pushing wine production back home, they force us to use more costly resources—to sacrifice more olive oil and cheese than necessary—to get the same wine. The result is a net loss of wealth.

Note that tariffs do not increase domestic production, they shift domestic production from one industry to another.

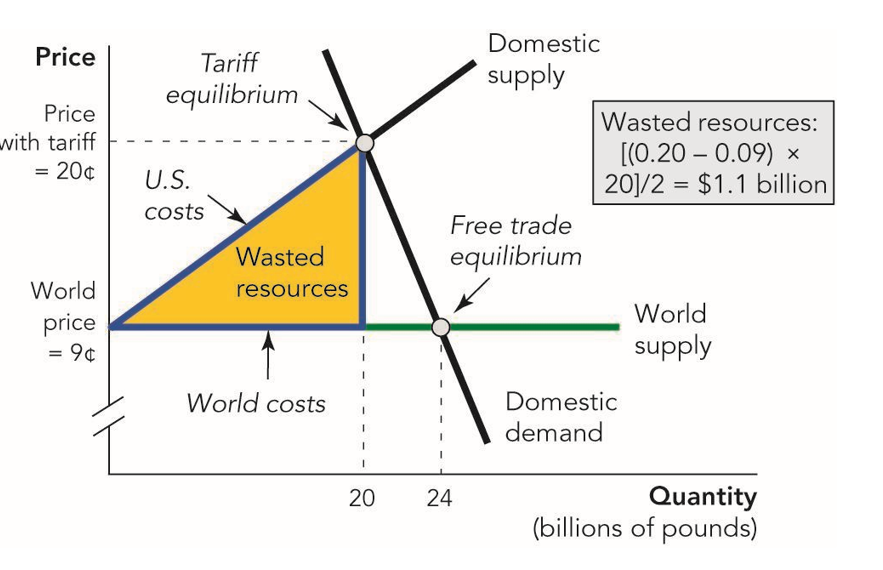

Here’s the diagram, taken from Modern Principles, using sugar as the example. Without the tariff, we could buy sugar at the world price of 9 cents per pound. The tariff pushes domestic production up to 20 billion pounds.

As the domestic sugar industry expands it pulls in resources from other industries. The value of those resources exceeds what we would have paid foreign producers. That excess cost is represented by the yellow area labeled wasted resources—the value of goods and services we gave up by redirecting resources to domestic sugar production instead of using them to produce other goods and services where we have a comparative advantage.

All of this, of course, is explained in Modern Principles, the best textbook for principles of economics. Needed now more than ever.

Five insights from farm animal economics

By Martin Gould, here is one excerpt:

Halting plans for a large, polluting factory farm feels like a clear win — no ammonia-laden air burning residents’ lungs, no waste runoff contaminating local drinking water, and seemingly fewer animals suffering in industrial confinement. But that last assumption deserves scrutiny. What protects one community might actually condemn more animals to worse conditions elsewhere.

Consider the UK: Local groups celebrate blocking new chicken farms. But because UK chicken demand keeps growing — it rose 24% from 2012-2022 — the result of fewer new UK chicken farms is just that the UK imports more chicken: it almost doubled its chicken imports over the same time period. While most chicken imported into the UK comes from the EU, where conditions for chickens are similar, a growing share comes from Brazil and Thailand, where regulations are nonexistent. Blocking local farms may slightly reduce demand via higher prices, but it also risks sentencing animals to worse conditions abroad.

The same problem haunts government welfare reforms — stronger standards in one country can just shift production to places with worse standards. But advocates are getting smarter about this. They’re pushing for laws that tackle both production and imports at once. US states like California have done this — when it banned battery cages, it also banned selling eggs from hens caged anywhere. The EU is considering the same approach. It’s a crucial shift: without these import restrictions, both farm bans and welfare reforms risk exporting animal suffering to places with even worse conditions. And advocates have prioritized corporate policies, which avoid this problem, as companies pledge to stop selling products associated with the worst animal suffering (like caged eggs), regardless of where they are produced.

Common sense from Ross Douthat

Now for my own view. I think trying to reshore some manufacturing and decouple more from China makes sense from a national security standpoint, even if it costs something to G.D.P. and the stock market. Using revenue from such a limited, China-focused tariff regime to pay down the deficit seems entirely reasonable.

I am more skeptical that such reshoring will alleviate specific male blue-collar social ills, because automation has changed the industries so much that I suspect you would need some sort of social restoration first to make the current millions of male work force dropouts more employable.

And I am extremely skeptical of any plan that treats pre-emptive global disruption as the key to avoiding a deficit crisis down the road. The “instigate a crisis now before our position weakens” has a poor track record in real wars — I don’t think trade wars are necessarily different.

Here is the full NYT piece. And from Armand Domalewski on Twitter: “there is no industry in America with stronger protectionism than the shipbuilding industry. The Jones Act makes it illegal to ship anything between two points in the US on a ship not built in the US and crewed by Americans. And yet America’s shipbuilding industry is nonexistent”

In Defense of Econ 101

People sometimes dismiss basic economic reasoning, “that’s just Econ 101!” yet most policymakers couldn’t pass the exam. Here’s an apropos bit from our excellent textbook, Modern Principles of Economics.

Do you shop at Giant, Safeway, or the Piggly Wiggly? If you do, you run a trade deficit with those stores. That is, you buy more goods from them than they buy from you (unless, of course, you work at one of these stores or sell them goods from your farm). The authors of this book also run a trade deficit with supermarkets. In fact, we have been running a trade deficit with Whole Foods for many years. Is our Whole Foods deficit a problem?

Our deficit with Whole Foods isn’t a problem because it’s balanced with a trade surplus with someone else. Who? You, the students, whether we teach you or whether you have bought our book. You buy more goods from us than we buy from you. We export education to you, but we do not import your goods and services. In short, we run a trade deficit with Whole Foods but a trade surplus with our students. In fact, it is only because we run a trade surplus with you that we can run a trade deficit with Whole Foods. Thanks!

The lesson is simple. Trade deficits and surpluses are to be found everywhere. Taken alone, the fact that the United States has a trade deficit with one country is not special cause for worry. Trade across countries is very much like trade across individuals. Not every person or every country can run a trade surplus all the time. Suddenly, a trade deficit does not seem so troublesome, even though the word “deficit” makes it sound like a problem or an economic shortcoming.

We continue on to discuss ” What if the United States runs a trade deficit not just with China or Japan or Mexico but with the world as a whole, as indeed it does? Is that a bad thing?”

Here’s a good Noah Smith piece if you want the details.