Category: Economics

Tyler’s Conversation with Jeff Sachs

It’s a great conversation. Sachs really opened up when discussing how his pediatrician wife influenced his approach to economics. The anger he still feels from the US treatment of Russia during its reform period is evident. He is startling forthright, calling out Acemoglu and Robinson and Krugman for mistakes and errors.

The youtube link is here. The audio edition is here and this is the ITunes link. Finally, here is the elegantly presented transcript on Medium, also with lots of links and additional material.

Sachs’ work on many fronts has influenced both Tyler and I, most notably in the geography section of our MRU development course.

Sentences to ponder, words of wisdom

The ageing societies of the rich world want rapid income growth and low inflation and a decent return on safe investments and limited redistribution and low levels of immigration. Well you can’t have all of that. And what they have decided is that what they’re prepared to sacrifice is the rapid income growth.

That is from Ryan Avent.

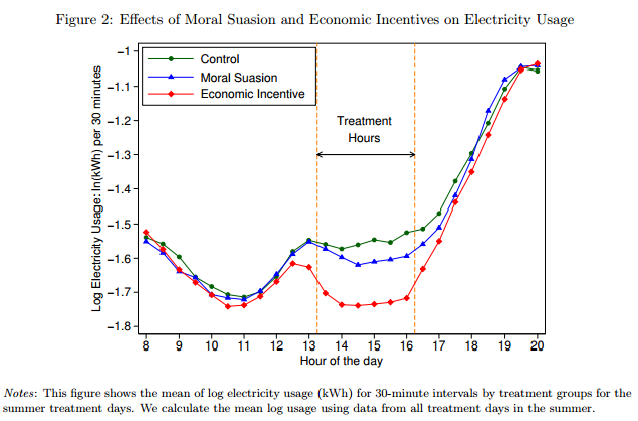

Moral Suasion vs. Price Incentives for Conservation

Given the water drought in California, Ito, Ido and Tanaka have a timely paper comparing two methods of electricity conservation. The authors assigned 691 households in Japan to one of three groups a) a moral suasion group, b) an economic incentive group or c) a control group. The moral suasion group were told that electricity conservation was important and necessary on peak demand days and then over a year when the peak times hit they were sent day-ahead and same-day messages to please reduce electricity consumption at the peak times. The economic incentive group were told that their electricity prices would be higher during certain peak periods and over the year when the peak times hit they were sent day-ahead and same-day messages telling then when the prices would be higher. Prices were approximately 2-4 times higher during the peak times. Control groups had smart meters installed but were not sent messages.

Moral suasion worked but not nearly as well as economic incentives (in the figure, lower use is better).

In fact, as the author’s discuss, the figure significantly underestimates the gains from the economic incentive because moral suasion worked only for the first few treatment periods and then faded away. The economic incentive continued to work throughout the treatment period. Moreover, precisely because people continued to respond to the incentive they developed a conservation habit so the group facing economic incentives actually conserved more during non-treatment periods and even after the experiment ended.

Hat tip: John Whitehead at Environmental Economics.

Addendum: Here are previous MR posts on water.

Compensating Differentials

The latest section of our Principles of Economics course at MRU is up today and it covers price discrimination and labor markets.

In this video, The Tradeoff Between Fun and Wages, we introduce the idea of compensating differentials in wages, an idea that goes back to Adam Smith.

Sharp readers will notice a homage near the beginning in what might otherwise appear to be an odd scene setting.

The Jeff Sachs chat

A live stream version is posted here, slide to 6:00 to start, YouTube and podcast and transcript versions are on their way. I thought Jeff did just a tremendous job. We covered the resource curse, why Russia failed and Poland succeeded, charter cities, his China optimism, how his recent book on JFK reflects the essence of his thought, why Paul Rosenstein-Rodan abandoned Austrian economics for “big push” ideas, whether Africa will be able to overcome the middle income trap, where he disagrees with Paul Krugman, his favorite novel (Doctor Zhivago, he tells us why too), premature deindustrialization, and how we should reform graduate economics education, among other topics.

Facts about low-income housing policy

Collinson, Ellen, and Ludwig have a new and long NBER paper (pdf) devoted to that topic. Here are a few bits:

The United States government devotes about $40 billion each year to means-tested housing programs, plus another $6 billion or so in tax expenditures on the Low Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC).

Yet total subsidies for home ownership may run as high as $600 billion, most of those not going to the poor.

There are over twenty different federal subsidized housing programs and most of them are no longer producing new units.

I am speaking for myself here, and not for the authors, but I cannot imagine any better case for cash transfers than to read this 75 pp. paper.

How about this?:

In 2012, housing authorities nationwide reported more than 6.5 million households on their waitlists for housing voucher or public housing.

That to my eye suggests targeting this aid is not working very well.

I found this to be an interesting comparison (I am not suggesting it is being driven by these federal housing policies):

The median renter household in 1960 was paying approximately 18 percent of his/her total family income in rent; the equivalent figure today is 29 percent.

Overall, I would like to see more economists call for the abolition of these programs and indeed some approximation of laissez-faire toward housing more generally.

Cowen Sachs live stream

You will find it here, and we start at 3:30, Eastern Standard Time, #CowenSachs.

The End of Asymmetric Information?

At Cato Unbound, Tyler and I ask whether the age of asymmetric information is ending and what implications this may have for regulation and markets. The Browser offers an excellent precis:

At Cato Unbound, Tyler and I ask whether the age of asymmetric information is ending and what implications this may have for regulation and markets. The Browser offers an excellent precis:

Sensors and reputation systems allow buyers to know what sellers know, principals to know what agents know, and vice-versa. Akerlof’s arguments have been overtaken. Any interested party can have access to information about product quality, worker performance, the nature of financial transactions. “A large amount of economic regulation seems directed at a set of problems which, in large part, no longer exist”

The end of asymmetric information will make markets work better but also governments. Here is one bit:

Many “public choice” problems are really problems of asymmetric information. In William Niskanen’s (1974) model of bureaucracy, government workers usually benefit from larger bureaus, and they are able to expand their bureaus to inefficient size because they are the primary providers of information to politicians. Some bureaus, such as the NSA and the CIA, may still be able to use secrecy to benefit from information asymmetry. For instance they can claim to politicians that they need more resources to deter or prevent threats, and it is hard for the politicians to have well-informed responses on the other side of the argument. Timely, rich information about most other bureaucracies, however, is easily available to politicians and increasingly to the public as well. As information becomes more symmetric, Niskanen’s (1974) model becomes less applicable, and this may help check the growth of unneeded bureaucracy.

We discuss used cars and Akerloff’s model for lemons, moral hazard problems, principal-agent problems, reputation mechanisms, computable contracts and much more.

We will be joined in future discussion by Joshua Gans, Shirley V. Svorny, and Jeff Ely.

Are S&P 500 firms now 5/6 “dark matter” or intangibles?

Justin Fox started it, and Robin Hanson has a good restatement of the puzzle:

The S&P 500 are five hundred big public firms listed on US exchanges. Imagine that you wanted to create a new firm to compete with one of these big established firms. So you wanted to duplicate that firm’s products, employees, buildings, machines, land, trucks, etc. You’d hire away some key employees and copy their business process, at least as much as you could see and were legally allowed to copy.

Forty years ago the cost to copy such a firm was about 5/6 of the total stock price of that firm. So 1/6 of that stock price represented the value of things you couldn’t easily copy, like patents, customer goodwill, employee goodwill, regulator favoritism, and hard to see features of company methods and culture. Today it costs only 1/6 of the stock price to copy all a firm’s visible items and features that you can legally copy. So today the other 5/6 of the stock price represents the value of all those things you can’t copy.

Check out his list of hypotheses. Scott Sumner reports:

Here are three reasons that others have pointed to:

1. The growing importance of rents in residential real estate.

2. The vast upsurge in the share of corporate assets that are “intangible.”

3. The huge growth in the complexity of regulation, which favors large firms.

It’s easy enough to see how this discrepancy may have evolved for the tech sector, but for the Starbucks sector of the economy I don’t quite get it. A big boost in monopoly power can create a larger measured role for accounting intangibles, but Starbucks has plenty of competition, just ask Alex. Our biggest monopoly problems are schools and hospitals, which do not play a significant role in the S&P 500.

Another hypothesis — not cited by Sumner or Hanson — is that the difference between book and market value of firms is diverging over time. That increasing residual gets classified as an intangible, but we are underestimating the value of traditional physical capital, and by more as time passes.

Cowen’s second law (“There is a literature on everything”) now enters, and leads us to Beaver and Ryan (pdf), who study biases in book to market value. Accounting conservatism, historical cost, expected positive value projects, and inflation all can contribute to a widening gap between book and market value. They also suggest (published 2000) that overestimations of the return to capital have bearish implications for future returns. It’s an interesting question when the measured and actual means for returns have to catch up with each other, what predictions this eventual catch-up implies, and whether those predictions have come true. How much of the growing gap is a “bias component” vs. a “lag component”? Heady stuff, the follow-up literature is here.

Perhaps most generally, there is Hulten and Hao (pdf):

We find that conventional book value alone explains only 31 percent of the market capitalization of these firms in 2006, and that this increases to 75 percent when our estimates of intangible capital are included.

So some of it really is intangibles, but a big part of the change still may be an accounting residual. Their paper has excellent examples and numbers, but note they focus on R&D intensive corporations, not all corporations, so their results address less of the entire problem than a quick glance might indicate. By the way, all this means the American economy (and others too?) has less leverage than the published numbers might otherwise indicate.

Here is a 552 pp. NBER book on all of these issues, I have not read it but it is on its way in the mail. Try also this Robert E. Hall piece (pdf), he notes a “capital catastrophe” occurred in the mid-1970s, furthermore he considers what rates of capital accumulation might be consistent with a high value for intangible assets. That piece of the puzzle has to fit together too. This excellent Baruch Lev paper (pdf) considers some of the accounting issues, and also how mismeasured intangible assets often end up having their value captured by insiders; that is a kind of rent-seeking explanation. See also his book Intangibles. Don’t forget the papers of Erik Brynjolfsson on intangibles in the tech world, if I recall correctly he shows that the cross-sectoral predictions line up more or less the way you would expect. Here is a splat of further references from scholar.google.com.

I would sum it up this way: measuring intangible values properly shows much of this change in the composition of American corporate assets has been real. But a significant gap remains, and accounting conventions, based on an increasing gap between book and market value, are a primary contender for explaining what is going on. In any case, there remain many underexplored angles to this puzzle.

Addendum: I wish to thank @pmarca for a useful Twitter conversation related to this topic.

It’s not the inequality, it’s the mobility

My latest column for The Upshot, at the NYT, is here. Here is one excerpt:

Data from the Economic Report of the President [p.34] suggests that if productivity growth had maintained its pre-1973 pace, the median or typical household would now earn about $30,000 more today. Those higher earnings would constitute a form of upward mobility. For purposes of comparison, if income inequality had maintained its pre-1973 trend, the gain for the median household would be about $9,000 in income this year, a much smaller figure.

Those changes in productivity and inequality trends aren’t entirely separate, but accelerating the growth of productivity has the potential to do more for upward economic mobility than redistributing money from the top 1 percent.

And this:

In the book “Equality for Inegalitarians,” George Sher, a professor of philosophy at Rice University, argues that the equality we should care most about is giving everyone a chance to “live effectively.” Most of all that means ensuring that people have enough for their daily needs. We can tolerate many of the inequalities that arise above this minimum income level, provided there is protection on the downside and plenty of opportunities for those who are economically ambitious.

Read Sher, Harry Frankfurt’s excellent forthcoming book On Inequality, Derek Parfit on equality and priority (pdf) and Huemer on Parfit (pdf). Read about prioritarianism more generally. I come away from these writings with the view that the current moral focus on inequality is a flat-out mistake in moral philosophy, analogous to how the philosophers sometimes make mistakes in economics. That’s right, not a difference in values but a mistake. (The difference in values, to the extent there is one, should be over the strength of our obligations to those at the bottom.)

This discussion of education provides another good example of how all this matters: if we successfully elevate people at the bottom, we don’t have to “fix” inequality.

A number of Twitter (and other) responses to my column are confusing several kinds of mobility: a) how many people from the bottom are elevated by how much, with b) what is the chance of people rising further quintiles?, and c) what is the intergenerational transmission of income and other variables? It’s a) that matters, as b) and c) run into many of the same problems that inequality notions do.

I also am not impressed by the “Gatsby Curve” observation that inequality and mobility (some kinds, some of the time) are correlated. Lots of things are correlated, but the question is what matters practically and morally.

By the way, here are estimates on how immigration might affect the Gini coefficient (pdf). I find that egalitarians have a hard time developing consistent intuitions about immigration.

Interfluidity offers a very different view from mine. Alex has much to say as well. Here is Schneider and Winship on the Gatsby Curve.

Here is my conclusion:

It is quite possible the future will bring higher levels of income inequality, which will undoubtedly distress many commentators. But we are likely to be better off if we keep our eye on the ball, identify what really helps people the most and do whatever we can to increase economic mobility. That is a practical program that we all should be able to endorse.

The Demand for R&D is Increasing

In my TED talk I said that if India and China were as rich as the United States is today then the market for cancer drugs would be eight times larger than it is now. Larger markets, both in size and wealth, increase the incentive to invest in R&D. Larger markets save lives. As India and China become richer, they are investing more in R&D and investing more in educating the scientists and engineers who produce new ideas, new ideas that benefit everyone.

The WSJ reports on this trend:

Chipscreen’s drug, called chidamide, or Epidaza, was developed from start to finish in China. The medicine is the first of its kind approved for sale in China, and just the fourth in a new class globally. Dr. Lu estimates the research cost of chidamide was about $70 million, or about one-tenth what it would have cost to develop in the U.S.

…China’s spending on pharmaceuticals is expected to top $107 billion in 2015, up from $26 billion in 2007, according to Deloitte China. It will become the world’s second-largest drug market, after the U.S., by 2020, according to an analysis published last year in the Journal of Pharmaceutical Policy and Practice.

China has on-the-ground infrastructure labs, a critical mass of leading scientists and interested investors, according to Franck Le Deu, head of consultancy McKinsey & Co.’s pharmaceuticals and medical-products practice in China. “There’re all the elements for the recipe for potential in China,” he said.

We have much to gain from increased wealth in the developing world.

Should Iceland abolish fractional reserve banking?

You are all familiar with their recent financial mishaps in Iceland, note also theirs is not a history of financial stability:

It is fair to say that Iceland’s monetary history has been a turbulent one. Currency controls in the 1920s to the 1950s were followed by chronic inflation in the 1970s to 1980s, with annual inflation reaching a high of 83% in 1983. In 1981 it was considered necessary to redenominate the krona with 100 units being replaced by 1 new unit.

That is from a new Frosti Sigurjónsson report (pdf) advocating 100 percent reserve banking for Iceland. In the “good old days” we had so many arguments against this arrangement — “disintermediation!” — but do those critiques hold up when so many nominal interest rates are in any case negative or close to zero? In many countries banks may be fated to become money warehouses as it is.

An interesting question is whether Iceland can, with its current size and export profile, ever have monetary and financial stability. With their exports and thus gdp so depending on fish and aluminum smelting and tourism, no other country shares their economic fluctuations, even roughly. A fixed rate thus means a non-optimum currency, but a floating rate for 323,002 people may mean perpetual whipsawing from international capital flows, not to mention the risk of acquiring an oversized, hard to bail out banking system, as Iceland did before its Great Recession.

Should I file under Department of Why Not? What if Scott Sumner asks me how to do this without inducing a collapse in nominal gdp? If I interpret p.78 of the study correctly, the government will create new money by printing and injecting it into the economy through fiscal policy, as a means of forestalling this problem if need be. Under this scenario, how powerful does the state become? On what do they spend the money?

Frosti’s report, by the way, was commissioned by the Prime Minister and it is being taken very seriously.

I believe I first saw notice of this link from Stephen Kinsella. Here are some responses to the idea. Zero Hedge seems sympathetic.

The forthcoming Akerlof and Shiller book

Phishing for Phools: The Economics of Manipulation and Deception.

Due out September 6, I have pre-ordered of course. Hat tip goes to Cass Sunstein.

What should I ask Jeffrey Sachs?

I may not follow any of your suggestions, but thought I should ask for advice, for my dialogue with Jeff next week. I am the interviewer, he is the interviewee, more or less. Keep in mind the goal here is to have an interesting and constructive dialogue, not to repeat the usual petty squabbles.

#CowenSachs, and you can sign up for the live stream here.

By the way, I thought you had many good suggestions for questions for Peter Thiel.

My conversation with Peter Thiel

The YouTube version is here, the podcast version is here.

I was very happy with how it turned out, as I deliberately set out not to copy the content of any of Peter’s other dialogues. You can learn how he thinks we will leave the “great stagnation,” whether the AI hype is justified, how he would boil his thought down to the smallest number of dimensions, whether NYC is over- or underrated, why globalization is likely to decline and what that means for different regions, the parts of the Bible which have influenced him most, “the Straussian Jesus,” to what age he thinks he will live, why Japan is special, how his German background matters, his favorite opening chess move, how and why company names matter, and even his favorite TV show, which he calls “schlocky.”

And much, much more, with commentary and questions from me throughout. A transcript is being prepared as well.