Category: Law

My excellent Conversation with Helen Castor

Here is the audio, video, and transcript. Here is part of the episode summary:

Tyler and Helen explore what English government could and couldn’t do in the 14th century, why landed nobles obeyed the king, why parliament chose to fund wars with France, whether England could have won the Hundred Years’ War, the constitutional precedents set by Henry IV’s deposition of Richard II, how Shakespeare’s Richard II scandalized Elizabethan audiences, Richard’s superb artistic taste versus Henry’s lack, why Chaucer suddenly becomes possible in this period, whether Richard II’s fatal trip to Ireland was like Captain Kirk beaming down to a hostile planet, how historians continue to discover new evidence about the period, how Shakespeare’s Henriad influences our historical understanding, Castor’s most successful work habits, what she finds fascinating about Asimov’s I, Robot, the subject of her next book, and more.

Here is an excerpt from the opening sequence:

COWEN: Richard II and Henry IV — they’re born in the same year, namely 1367. Just to frame it for our listeners, could you give us a sense — back then, what was it that the English government could do and what could it not do? What is the government like then?

CASTOR: I think people might be surprised at quite how much government could do in England at this point in history because England, at this point, was the most centralized state in Europe, and that has two reasons. One is the Conquest of 1066 where the Normans have come in and taken the whole place over. Then, the other key formative period is the late 12th century when Henry II is ruling an empire that stretches from the Scottish border all the way down to southwestern France.

He has to have a system of government and of law that can function when he’s not there. By the late 14th century, when Richard and Henry — my two kings in this book — appear on the scene, the king has two key functions which appear on the two sides of his seal. On one side, he sits in state wearing a crown, carrying an orb and scepter as a lawgiver and a judge. That is a key function of what he does for his people. He imposes law. He gives justice. He maintains order.

On the other side of the seal, he’s wearing armor on a warhorse with a sword unsheathed in his hand. That’s his function as a defender of the realm in an intensely practical way. He has to be a soldier, a warrior to repel attacks or, indeed, to launch attacks if that’s the best form of defense. To do that, he needs money.

For that, the institution of parliament has developed, which offers consent to taxation that he can demonstrate is in the national interest. It has also come to be a law-making forum. Wherever he needs to make new laws, he can make statute law in Parliament that therefore, in its very nature, has the consent of the representatives of the realm.

COWEN: What is it, back then, that government cannot do?

CASTOR: What a government doesn’t have in the medieval period is, it doesn’t have a monopoly of force. In other words, it doesn’t have a police force. It doesn’t have a professional police force, and it doesn’t have a standing army, or at least by the late Middle Ages, England does have a permanent garrison in Calais, which is its outpost on the northern coast of France, but that’s not a garrison that can be recalled to England with any ease.

So, enforcement is the government’s key problem. To enforce the king’s edicts, it therefore relies on a hierarchy of private power on the landed, the great landowners of the kingdom, who are wealthy because of their possession of land, but crucially, also have control over people, the men who live and work on their land. If you need to get an enforcement posse — this is medieval English language that we use when we talk of sheriffs and posses — the county posse, the power of the county.

If you need to get men out quickly, you need to tap into those local power structures. You don’t have modern communications. You don’t have modern transport. The whole hierarchy of the king’s theoretical authority has to tap into and work through the private hierarchy of landed power.

COWEN: Why do those landed nobles obey the king? They’re afraid of the future raising of an army? Or they’re handed out some other benefit? What keeps the incentives all working together to the extent they stay working together?

CASTOR: They have a very important pragmatic interest in obeying the king because the king is the keystone of the hierarchy within which they are powerful and wealthy. Of course, they want more power and more wealth for themselves and for their dynasty, but importantly, they don’t want to risk everything to acquire more if it means serious danger that they might lose what they already have.

They have every interest in maintaining the hierarchy as it already is, within which they can then . . . It’s like having a referee…

A very good episode, definitely recommended. I enjoyed all of Helen’s books, most notably the recent

Shorting Your Rivals: A Radical Antitrust Remedy

Conventional antitrust enforcement tries to prevent harmful mergers by blocking them but empirical evidence shows that rival stock prices often rise when a merger is blocked—suggesting that many blocked mergers would have increased competition. In other words, we may be stopping the wrong mergers.

In a clever proposal, Ayres, Hemphill, and Wickelgren (2024) argue that requiring merging firms to short the stock of a close competitor would powerfully realign incentives.

Suppose firms A and B want to merge. Regulators allow the merger on one condition: A-B must take a sizable short position in firm C, a direct competitor. If the merger is anti-competitive and leads to higher industry prices, C’s profits and stock price rise, and A-B takes a financial hit. But if the merger is pro-competitive and drives prices down, C’s stock falls and A-B profits.

A short creates two desirable effects:

- Selection Effect: Only those mergers that are expected to lower prices (and hurt rivals) are financially attractive to the merging parties.

- Incentive Effect: Post-merger, A-B has less incentive to raise prices because doing so boosts C’s stock price, triggering losses on the short.

The short isn’t perfect. Markets might be too shallow, or the rival’s stock could rise for unrelated reasons which imposes extra risk. The authors suggest fixes: instead of a short, require the firm to write Margrabe-style call option. These options have strike prices which float relative to another asset, for example a market or industry price. In this case, A-B would be penalized not if the market as a whole rose but only if the rival outperforms the market.

But the cleanest solution doesn’t require financial instruments at all. Just tie executive pay to relative performance—make the A-B CEO’s bonus depend on beating C’s performance. This is good for shareholders, aligns incentives even in private markets, and doesn’t require making big public bets.

Shorting your rivals sounds strange. But it’s a clever way to force firms to reveal whether their merger helps consumers—or just themselves. Or as I like to say, a bet is a tax on bullshit.

Hat tip: Kevin Lewis.

Addendum: See also this earlier paper, Incentive Contracts as Merger Remedies by Werden, Froeb and Tschantz.

D’accord !

That is from the French embassy in the UK.

The political culture/holiday culture that is French

The French government proposed cutting two public holidays per year to boost economic growth as part of a budget plan that it billed as a “moment of truth” to avoid a financial crisis. But in a country where vacations are sacred, the idea — unsurprisingly — prompted outrage across the political spectrum, suggesting it may have little chance of becoming law.

Here is more from Annabelle Timsit at the Washington Post. How many countries will, over the next ten years, in fact prove governable?

The Role of Blood Plasma Donation Centers in Crime Reduction

The United States is one of the few OECD countries to pay individuals to donate blood plasma and is the most generous in terms of remuneration. The opening of a local blood plasma center represents a positive, prospective income shock for would-be donors. Using detailed data on the location of blood plasma centers in the US and two complementary difference-indifferences research designs, we study the impact of these centers on crime outcomes. Our findings indicate that the opening of a plasma center in a city leads to a 12% drop in the crime rate, an effect driven primarily by property and drug-related offenses. A within-city design confirms these findings, highlighting large crime drops in neighborhoods close to a newly opened plasma center. The crime-reducing effects of plasma donation income are particularly pronounced in less affluent areas, underscoring the financial channel as the primary mechanism behind these results. This study further posits that the perceived severity of plasma center sanctions against substance use, combined with the financial channel, significantly contributes to the observed decline in drug possession incidents.

That is from a new paper by Brendon McConnell and Mariyana Zapryanova. Via the excellent Kevin Lewis.

To what extent will factories return to cities?

Cities and small towns have tried to revitalize their downtowns by rolling back certain rules and requirements to help promote new developments and bring life to empty streets.

Now, they’re returning to an earlier era, when craftspeople such as food makers, woodworkers and apparel designers were integral parts of neighborhood life, and economic activity revolved around them.

New York City changed its zoning rules last year for the first time in decades to allow small-scale producers in neighborhoods where they had long been restricted. The City of Elgin, a suburb of Chicago, approved a code change last fall allowing retailers to make and sell products in the same space. In 2022, Baltimore passed a bill that allows small-scale food processing and art-studio-related businesses in commercial zones.

And Seattle’s City Council will vote in September on a plan that includes changing rules to allow artisan manufacturers in residential neighborhoods. Supporters said the proposal would help create the kind of walkable mixed-use neighborhoods that were common in an earlier era.

…Over the past decade, hundreds of U.S. cities and small towns have revised their land-use codes to allow small-scale producers — from coffee roasters to makers of jewelry and furniture — in downtowns and neighborhoods. Many small producers started to disappear from those areas around the turn of the 20th century with the advent of mass production; as large-scale factories generated enormous waste and pollution, cities restricted them near residences. Now, most of the businesses allowed to operate under the new rules employ between one and 30 people.

Blame Canada! Measles Edition

Polimath has a good post on measles. The recent spike in U.S. cases has drawn alarm. As the New York Times reports:

There have now been more measles cases in 2025 than in any other year since the contagious virus was declared eliminated in the United States in 2000, according to new data released Wednesday by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The grim milestone represents an alarming setback for the country’s public health and heightens concerns that if childhood vaccination rates do not improve, deadly outbreaks of measles — once considered a disease of the past — will become the new normal.

But as Polimath notes, U.S. vaccination rates remain above 90% nationally. The problem isn’t broad domestic anti-vax sentiment but rather concentrated gaps in coverage, often within insular religious communities. These local shortfalls do explain how outbreaks spread once they begin—but how do they begin in the first place, given these communities are islands within a largely vaccinated country? Polimath says blame Canada! (and Mexico!)

The greater concern in my mind is not the problem of low measles vaccination coverage in the United States, but among our immediate neighbors. In Ontario, the MMR vaccination rate among 7-year-olds is under 70%. As in the examples above, this rate seems to be particularly low “in specific communities”, whatever that is supposed to mean. This has resulted in the ongoing spread of measles such that Ontario’s measles infection rate is 40 times higher than the United States. Canada officially “eliminated” measles in 1998. But with vaccine rates as low as they are, it seems like Canada is at risk for losing that “elimination” status and becoming an international source for measles.

Similarly, Mexico is having a measles outbreak that is substantially worse than the US outbreak. Importantly, the Mexican outbreak has been the worst in the Chihuahua province (over 3,000 cases), which borders Texas and New Mexico.

I’m less interested in blame than in the useful reminder that not all politics is American politics. Vaccination rates have dipped worldwide and not in response to U.S. politics or RFK Jr. In fact, despite RFK Jr. the U.S. is doing better than some of its North American and European peers. Outbreaks here may be triggered by cross-border exposure, not failures in U.S. public health alone. Not all politics is American—and not all American outcomes are made in America.

Hat tip: the excellent Stephen Landry.

Surveillance is growing

California residents who launched fireworks for the 4th of July have tickets coming in the mail, thanks to police drones that were taking note. One resident, for example, racked up $100,000 in fines last summer due to the illegal use of fireworks. “If you think you got away with it, you probably didn’t,” said Sacramento Fire Department Captain Justin Sylvia. “What may have been a $1,000 fine for one occurrence last year could now be $30,000 because you lit off so many.” Homeowners who weren’t even present at the property also have tickets coming in the mail due to the social host ordinance.

Here is the source. Elsewhere (NYT):

Hertz and other agencies are increasingly relying on scanners that use high-res imaging and A.I. to flag even tiny blemishes, and customers aren’t happy…

Developed by a company called UVeye, the scanning system works by capturing thousands of high-resolution images from all angles as a vehicle passes through a rental lot’s gates at pickup and return. A.I. then compares those images and flags any discrepancies.

The system automatically creates and sends damage reports, Ms. Spencer said. An employee reviews the report only if a customer flags an issue after receiving the bill. She added that fewer than 3 percent of vehicles scanned by the A.I. system show any billable damage.

I await the next installment in this series.

What does one hundred percent reserves for stablecoins mean?

I asked o3 pro about the Genius Act, and it gave me this answer (there is more at the link), consistent with other responses I have heard:

The statute’s policy goal is to keep a payment‑stablecoin issuer from morphing into a fractional‑reserve bank or a trading house while still giving it enough freedom to:

-

hold the specified reserve assets and manage their maturities;

-

use overnight Treasuries repo markets for cash management (explicitly allowed);

-

provide custody of customers’ coins or private keys.

Everything else—consumer lending, merchant acquiring, market‑making, proprietary trading, staking, you name it—would require prior approval and would be subject to additional capital/liquidity rules.

Recall also that the stablecoins are by law prohibited from paying interest, though the backing assets, such as T-Bills, will pay interest to the stablecoin issuer. Thus when nominal interest rates are high, the issuer will earn a decent spread and have no problem covering costs. When nominal interest rates are low or zero, fees on stablecoin issuance might be required, otherwise there is no way to cover the basic costs of operation.

What will be the costs of intermediation? In the financial sector as a whole, they are arguably about two percent. For money market funds, however, they are closer to 0.2 percent. (Since these entities will be strictly regulated, we cannot estimate fees by looking at current major stablecoin issuers. Across some different inquiries, o3 pro gave me intermediation cost estimates ranging from 0.8 percent to 3 percent.) Whatever number will be the case here, the intermediaries may need to resort to fees if market interest rates are very low, in order to break even. That may in turn induce individuals to yank money out of the accounts — who wants to keep paying those fees?

Perhaps a more likely problem would stem from interest rates that are fairly high. In that case, why hold zero-yielding stablecoins? The sector will again contract, though in an orderly fashion.

Perhaps the sector and its intermediaries are most stable for some band of interest rates “in the middle”?

Inspections of the backing assets are supposed to take place every month, though the regulator can take a look any time. I am not sure what is the optimal frequency. But I worry there is sometimes no “efficiency wage profit margin” to induce responsible behavior. After all, the issuers have no other lines of business and no other sources of revenue. Non-pecuniary competition for deposits might reduce profits further (“come get your free toaster!”). Thus being kicked out of the sector is no major penalty (for those parameter values), which puts a significant burden on the possibility of legal and felony punishments. It can be hard to pull the trigger on those, however.

If interest rates are somewhat higher though, the desire to keep that profit will create an economic incentive for responsible behavior, above and beyond the fear of legal penalties.

As I understand the legislation, the level of interest rates seems important for sector stability and also for the size of the sector. That is because there are no interest payments on stablecoins that can adjust with the underlying rates on the T-Bills. Perhaps that feature of the legislation should be reconsidered? Or perhaps issuer competition across non-pecuniary yields on the accounts will serve a sufficiently comparable purpose?

GAVI’s Ill-Advised Venture Into African Industrial Policy

GAVI, the Vaccine Alliance has saved millions of lives by delivering vaccines to the world’s poorest children at remarkably low cost. It’s frankly grotesque that RFK Jr. cites “safety” as a reason to cut funding—when the result of such cuts will be more children dying from preventable diseases. Own it.

You can find plenty of RFK Jr. criticism elsewhere, however, and GAVI is not above criticism. Thus, precisely because GAVI’s mission is important, I want to focus on a GAVI project that I think is ill-motivated and ill-advised, GAVI’s African Vaccine Manufacturing Accelerator (AVMA).

The motivation behind the AVMA is to “accelerate the expansion of commercially viable vaccine manufacturing in Africa” to overcome “vaccine inequity” as illustrated during the COVID crisis. The problem with this motivation is that most of Africa’s delay in receiving COVID vaccines was driven by funding issues and demand rather than supply. Working with Michael Kremer and others, I spent a lot of time encouraging countries to order vaccines and order early not just to save lives but to save GDP. We were advisors to the World Bank and encouraged them to offer loans but even after the World Bank offered billions in loans there was reluctance to spend big sums. There were supply shortages in 2021 in Africa, as there were elsewhere, but these quickly gave way to demand issues. Doshi et al. (2024) offer an accurate summary:

Several reasons likely account for low coverage with COVID-19 vaccines, including limited political commitment, logistical challenges, low perceived risk of COVID-19 illness, and variation in vaccine confidence and demand (3). Country immunization program capacity varies widely across the African Region. Challenges include weak public health infrastructure, limited number of trained personnel, and lack of sustainable funding to implement vaccination programs, exacerbated by competing priorities, including other disease outbreaks and endemic diseases as well as economic and political instability.

Thus, lack of domestic vaccine production wasn’t the real problem—remember, most developed countries had little or no domestic production either but they did get vaccines relatively quickly. The second flaw in the rationale for the AVMA is its pan-African framing. Africa is a continent, not a country. Why would manufacturing capacity in Senegal serve Kenya better than production in India or Belgium? There’s a peculiar assumption of pan-African solidarity, as if African countries operate with shared interests that go beyond those observed in other countries that share a continent.

Both problems with the rationale for AVMA are illustrated by South Africa’s Aspen pharmaceuticals. Aspen made a deal to manufacture the J&J vaccine in South Africa but then exported doses to Europe. After outrage ensued it was agreed that 90% of the doses would be kept in Africa but Aspen didn’t receive a single order from an African government. Not one.

Now to the more difficult issue of capacity. Africa produces less than .1% of the world’s vaccines today. The African Union has what it acknowledges is an “ambitious goal” to produce over 60 percent of the vaccines needed for Africa’s population locally by 2040. To evaluate the plausibility of this goal do note that this would require multiple Serum‑of‑India‑sized plants.

More generally, vaccines are complex products requiring big up-front investments and long lead times:

Vaccine manufacturing is one of the most demanding in industry. First, it requires setting up production facilities, and acquiring equipment, raw materials, and intellectual property rights. Then, the manufacturer will implement robust manufacturing processes and manage products portfolio during the life cycle. Therefore, manufacturers should dispose of an experienced workforce. Manufacturing a vaccine is costly and takes seven years on average. For instance, it took about 5–10 years to India, China, and Brazil to establish a fully integrated vaccine facility. A longer establishment time can be expected for African countries lacking dedicated expertise and finance. Manufacturing a vaccine can costs several dozens to hundreds of million USD in capital invested depending on the vaccine type and disease indication.

All countries in Africa rank low on the economic complexity index, a measure of whether a country can produce sophisticated and complex products (based on the diversity and complexity of their export basket). But let us suppose that domestic production is stood up. We must still ask, at what price? If domestic manufacturing ends up being more expensive than buying abroad (as GAVI acknowledges is a possibility even with GAVI’s subsidies), will African countries buy “locally” and pay more or will solidarity go out the window?

Finally, even if complex vaccines are produced at a competitive price, we still haven’t solved the demand problem. GAVI again has a rather strange acknowledgment of this issue:

Secondly, adequate country demand is another critical enabler. For AVMA to be successful, African countries will need to buy the vaccines once they appear on the Gavi menu. The Secretariat is committed to ongoing work with the AU and Member States on demand solidarity under Pillar 3 of Gavi’s Manufacturing Strategy.

So to address vaccine inequity, GAVI is investing in local production….but the need to manufacture “demand solidarity” among African governments reveals both the flaw in the premise and the weakness of the plan.

Keep in mind that the WHO only recognizes South Africa and Egypt as capable of regulating the domestic production of vaccines (and Nigeria as capable of regulating vaccine imports). In other words, most African governments do not have regulatory systems capable of evaluating vaccine imports let alone domestic production.

GAVI wants to sell the AVMA as if were an AMC (Advance Market Commitment) but it isn’t. It’s industrial policy. An AMC would offer volume‑and‑price guarantees open to any manufacturer in the world. An AMC with local production constraints is a weighted down AMC, less likely to succeed.

None of this is to imply that GAVI has no role to play. In addition to a true AMC, GAVI could arrange contracts to pay existing global suppliers to maintain idle capacity that can pivot to African‑priority antigens within 100 days. GAVI could possibly also help with regulatory convergence. There is an African Medicines Agency which aims to operate like the EMA but it has only just begun. If the AMA can be geared up, it might speed up vaccine approval through mutual recognition pacts.

The bottom line is that the $1.2 billion committed to AVMA would likely better more lives if it was directed toward GAVI’s traditional strengths in pooled procurement and distribution, mechanisms that have proven successful over the past two decades. Instead, AVMA drags GAVI into African industrial policy. A poor gamble.

Labour considers fast-tracking approval of big projects

There are a few modest signs of progress in the UK (and Canada):

Ministers are exploring using the powers of parliament to cut the time it takes to approve new railways, power stations and other infrastructure projects.

In an attempt to promote growth, the government is examining whether it could pass legislation that would allow transport, energy and new town housing projects to circumvent swathes of the planning process.

The move could limit the ability of opponents to challenge projects in the courts and reduce scrutiny of some developments. It is loosely modelled on a Canadian scheme that was the brainchild of Mark Carney, the new prime minister and a former governor of the Bank of England.

The One Canadian Economy Act was passed by Canada’s parliament in June and gives Carney’s government powers to fast-track national projects. The Treasury is understood to be examining how a UK version could speed up the approval process for nationally significant infrastructure projects, such as offshore wind farms or even a third runway at Heathrow.

Here is more from The Times.

Tom Tugendhat on British economic stagnation

Second, and even more detrimental to younger generations, is a set of policies that have artificially created a highly damaging cult of housing. For many decades, too few houses have been built in the UK. Thanks in part to the tax system, housing has been transformed from a place to live and raise a family into a de facto tax free retirement fund that excludes the young. More than 56 per cent of the UK’s total housing wealth is owned by those over 60, while home ownership among those under 35 has collapsed to just 6 per cent. This has had profound social and economic consequences as fewer people marry and have children, further impairing long-term demographic regeneration. The result? More than 80 per cent of the growth in real per capita wealth over the past 30 years has come from appreciation of real estate, not from the financial investment that powers the economy.

Michael Tory, co-founder of Ondra Partners, has argued that this capital misallocation has created a self-reinforcing cycle, weakening our national and economic security. Without productive capital, we are wholly dependent on foreign investment and imported labour, straining housing supply and public services. These distortions can only be corrected through a rebalancing of our national capital allocation that puts long-term national interest above narrow electoral calculation. That means levelling the investment playing field to reduce the taxes on those whose long-term savings and investments in Britain’s future actually employ people and generate growth. Along with building more houses and stricter migration controls, this would bring home ownership into reach for younger generations.

British pension funds should invest more in British businesses as well. Here is more from the FT.

Trump Accounts are a Big Deal

Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill Act was signed into law on July 4, 2025. It’s so big that many significant features have been little discussed. Trump Accounts are one such feature under which every newborn citizen gets $1000 invested in the stock market. These accounts could radically change social welfare in the United States and be one important step on the way to a UBI or UBWealth. Here are some details:

- Government Contribution: A one-time $1,000 contribution per eligible child, invested in a low-cost, diversified U.S. stock index fund.

- Eligibility: U.S. citizen children born between January 1, 2025, and December 31, 2028 (with a valid Social Security number and at least one parent with a valid Social Security number).

- Employer Contributions: Employers can contribute up to $2,500 annually per employee’s child, and these contributions are excluded from the employee’s gross income for tax purposes. These are subject to the overall $5,000 annual contribution limit (indexed for inflation) per child (which includes parental contributions).

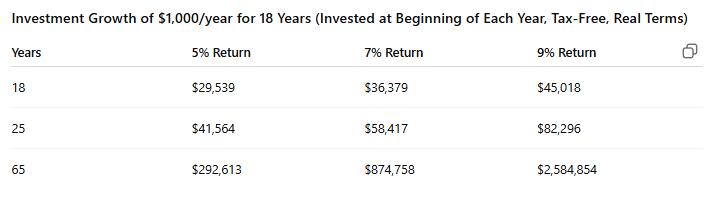

The employer contribution strikes me as important. Suppose that in addition to the initial $1000 government payment that on average $1000 is added per year for 18 years (by a combination of parent and parent employer contributions). Note that this is below the maximum allowed annual contribution of $5000. At a historically reasonable 7% real rate of return these accounts will be worth ~36k at age 18 (when the money can be fully withdrawn), $58k at age 25 and $875k at age 65 subject to uncertainty of course as indicated below.

The $1000 initial payment is available only for newborns but, as I read the text, the parent and employer donations can be made for any child under the age of 18 so this is basically an IRA for children. It’s slightly complicated because if the child or parents put after-tax money into the account that is not taxed at withdrawal (you get your basis back) but everything else is taxed on withdrawal as ordinary income like an IRA. There are approximately 3.5 million citizen births a year so the program will have direct costs of $3.5 billion plus indirect costs from reduced taxes due to the tax-free yearly contribution allowance, which as noted could be quite large as it can go to any child. Thus the program could be quite expensive. On the other hand, it’s clear that the accounts could reduce reliance on social security if held for long periods of time. The $1000 initial contribution is limited to four years but once 14 million kids get them, the demand will be to make them permanent.

BBB on drug price negotiations

The sweeping Republican policy bill that awaits President Trump’s signature on Friday includes a little-noticed victory for the drug industry.

The legislation allows more medications to be exempt from Medicare’s price negotiation program, which was created to lower the government’s drug spending. Now, manufacturers will be able to keep those prices higher.

The change will cut into the government’s savings from the negotiation program by nearly $5 billion over a decade, according to an estimate by the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office.

…the new bill spares drugs that are approved to treat multiple rare diseases. They can still be subject to price negotiations later if they are approved for larger groups of patients, though the change delays those lower prices.

This is the most significant change to the Medicare negotiation program since it was created in 2022 by Democrats in Congress.

Here is more from the NYT. Knowledge of detail is important in such matters, but one hopes this is the good news it appears to be.

Genetic Counseling is Under Hyped

In an excellent interview (YouTube; Apple Podcasts, Spotify) Dwarkesh asked legendary bio-researcher George Church for the most under-hyped bio-technologies. His answer was both surprising and compelling:

What I would say is genetic counseling is underhyped.

What Church means is that gene editing is sexy but for rare diseases carrier screening is cheaper and more effective. In other words, collect data on the genes of two people and let them know if their progeny would have a high chance of having a genetic disease. Depending on when the information is made known, the prospective parents can either date someone else or take extra precautions. Genetic testing now costs on the order of a hundred dollars or less so the technology is cheap. Moreover, it’s proven.

Since the early 1980s the Jewish program Dor Yeshorim and similar efforts have screened prospective partners for Tay-Sachs and other mutations. Before screening, Tay-Sachs struck roughly 1 in 3,600 Jewish births; today births with Tay-Sachs have fallen by about 90 percent in countries that adopted screening programs. As more tests are developed they can be easily integrated into the process. In addition to Tay-Sachs, Dor Yeshorim, for example, currently tests for cystic fibrosis, Bloom syndrome, and spinal muscular atrophy among other diseases. A program in Israel reduced spinal muscular atrophy by 57%. A study for the United States found that a 176 panel test was cost-effective compared to a minimal 5 panel test as did a similar study on a 569 panel test for Australia.

A national program could offer testing for everyone at birth. The results would then be part of one’s medical record and could be optionally uploaded to dating websites. In a world where Match.com filters on hobbies and eye color, why not add genetic compatibility?

Do it for the kids.

Addendum: See also my paper on genetic insurance (blog post here).