Category: Law

My excellent Conversation with David Commins

Saudi Arabia and the Gulf are the topics, here is the audio, video, and transcript. Here is the episode summary:

David Commins, author of the new book Saudi Arabia: A Modern History, brings decades of scholarship and firsthand experience to explain the kingdom’s unlikely rise. Tyler and David discuss why Wahhabism was essential for Saudi state-building, the treatment of Shiites in the Eastern Province and whether discrimination has truly ended, why the Saudi state emerged from its poorer and least cosmopolitan regions, the lasting significance of the 1979 Grand Mosque seizure by millenarian extremists, what’s kept Gulf states stable, the differing motivations behind Saudi sports investments, the disappointing performance of King Abdullah University of Science and Technology despite its $10 billion endowment, the main barrier to improving its k-12 education, how Yemen became the region’s outlier of instability and whether Saudi Arabia learned from its mistakes there, the Houthis’ unclear strategic goals, the prospects for the kingdom’s post-oil future, the topic of David’s next book, and more.

And an excerpt:

COWEN: Now, as you know, the senior religious establishment is largely Nejd, right? Why does that matter? What’s the historical significance of that?

COMMINS: Right. Nejd is the region of central Arabia. Riyadh is currently the capital. The first Saudi empire had a capital nearby, called Diriyah. Nejd is really the territory that gave birth to the Wahhabi movement, it’s the homeland of the Saud dynasty, and it is the region of Arabia that was most thoroughly purged of the older Sunni tradition that had persisted in Nejd for centuries.

Consequently, by the time that the Saudi government developed bureaucratic agencies in the 1950s and ’60s, the religious institution was going to recruit from that region of Arabia primarily. Now, it certainly attracted loyalists from other parts of Arabia, but the Wahhabi mission, as I call it — their calling to what they considered true belief — began in Nejd and was very strongly identified with the towns of Nejd ever since the late 1700s.

COWEN: Would I be correct in inferring that some of the least cosmopolitan parts of Saudi Arabia built the Saudi state?

COMMINS: Yes, that is correct. That is correct. If you think of the 1700s and 1800s, the Red Sea and Persian Gulf coast of Arabia were the most cosmopolitan parts of Arabia.

COWEN: They’re richer, too, right? Jeddah is a much more advanced city than Riyadh at the time.

COMMINS: Somewhat more advanced. Yes, it is more advanced, it is more cosmopolitan than Nejd. There is the regional identity in Hejaz, that is the Red Sea coast where the holy cities and Jeddah are located. The townspeople there tended to look upon Nejd as a less advanced part of Arabia. But again, that’s a very recent historical development.

COWEN: How is it that the coastal regions just dropped the ball? You could imagine some alternate history where they become the center of Saudi power and religious thought, but they’re not.

COMMINS: Right. If you take Jeddah, Mecca, and Medina — that region of Arabia, known as Hejaz, had always been under the rule of other Muslim empires. They were under the rule of other Muslim powers because of the religious value of possessing, if you will, the holy cities, Mecca and Medina. From the time of the first Muslim dynasty that was based in Damascus in the seventh and early eighth centuries, all the way until the Ottoman Empire, Muslim dynasties outside Arabia coveted control of that region. They were just more powerful than local resources could generate.

Hejaz was always, if you were, to dependency on outside Muslim powers. If you look at the east coast of Arabia — what’s now the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia and the Persian Gulf — it was richer than central Arabia. It’s the largest oasis in Arabia. It is in proximity to pearling banks, which were an important source for income for residents there. It was part of the Indian Ocean trade between Iraq and India. The population there was always — well, always — for the last thousand years has been dominated by Bedouin tribesmen.

There was a brief Ismaili Shia republic, you might say, in that part of Arabia in medieval times. It just didn’t have, it seems, the cohesion to conquer other parts of Arabia. That’s what makes the Saudi story really remarkable, is that they were able to muster and sustain the cohesion to carry out a conquest like that over the course of 50 years.

COWEN: Physically, how did they manage that? Water is a problem, a lot of transport is by camel, there’s no real rail system, right?

Recommended, full of historical information about a generally neglected region, neglected from the point of view of history at least rather than current affairs.

Summary of a new DeepMind paper

Super intriguing idea in this new @GoogleDeepMind paper – shows how to handle the rise of AI agents acting as independent players in the economy.

It says that if left unchecked, these agents will create their own economy that connects directly to the human one, which could bring both benefits and risks.

The authors suggest building a “sandbox economy,” which is a controlled space where agents can trade and coordinate without causing harm to the broader human economy.

A big focus is on permeability, which means how open or closed this sandbox is to the outside world. A fully open system risks crashes and instability spilling into the human economy, while a fully closed system may be safer but less useful.

They propose using auctions where agents fairly bid for resources like data, compute, or tools. Giving all agents equal starting budgets could help balance power and prevent unfair advantages.

For larger goals, they suggest mission economies, where many agents coordinate toward one shared outcome, such as solving a scientific or social problem.

The risks they flag include very fast agent negotiations that humans cannot keep up with, scams or prompt attacks against agents, and powerful groups dominating resources.

To reduce these risks, they call for identity and reputation systems using tools like digital credentials, proof of personhood, zero-knowledge proofs, and real-time audit trails.

The core message is that we should design the rules for these agent markets now, so they grow in a safe and fair way instead of by accident.

That is from Rohan Paul, though the paper is by Nenad Tomasev, et.al. It would be a shame if economists neglected what is perhaps the most important (and interesting) mechanism design problem facing us.

Should we abolish mandatory quarterly corporate reporting?

President Trump has suggested doing that. I have not found a human source as good as GPT5, so I will cite that:

Theory predicts that more frequent reporting can exacerbate managerial short‑termism; some archival evidence finds lower investment when reporting frequency rises. But when countries reduced frequency (UK/EU), the average firm’s investment didn’t materially change—in part because most issuers kept giving quarterly updates anyway…

Will markets just insist on quarterly anyway? That’s what happened in the UK and Austria: after rules allowed semi‑annual reporting, only a small minority actually stopped quarterly updates; those that did often saw lower liquidity and less analyst coverage. So yes—many issuers kept some form of quarterly communication to satisfy investors.

There is much, much more at the link.

Intertemporal substitution

Across several Central American nations money transfers have jumped 20 percent.

The reason, officials, migrants and analysts say, is that people afraid of being deported are trying to get as much money out of the country as possible, while they still can.

The money transfers, called remittances, are a critical lifeline for many countries and families around the world, especially in Central America and the Caribbean. There, the funds sometimes make up a huge chunk of a nation’s economy — as much as a quarter of a country’s gross domestic product, as in Honduras and Nicaragua.

Here is more from James Wagner at the NYT.

What should I ask Cass Sunstein?

Yes, I will be doing a Conversation with him soon. Most of all (but not exclusively) about his three recent books Liberalism: In Defense of Freedom, Manipulation: What It Is, Why It Is Bad, What To Do About It, and Imperfect Oracle: What AI Can and Cannot Do.

So what should I ask him? Here is my previous CWT with Cass.

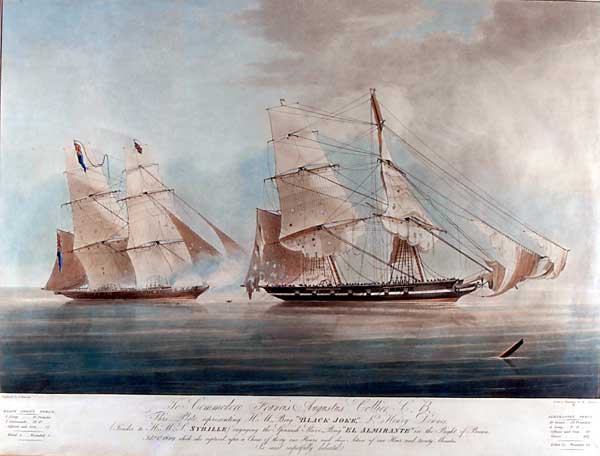

The British War on Slavery

In August of 1833 the British passed legislation abolishing slavery within the British Empire and putting more than 800,000 enslaved Africans on the path to freedom. To make this possible, the British government paid a huge sum, £20 million or about 5% of GDP at the time, to compensate/bribe the slaveowners into accepting the deal. In inflation adjusted terms this is about £2.5 billion today (2025) but relative to GDP the British spent an equivalent of about $170 billion to free the slaves, a very large expenditure.

Indeed, the expenditure was so large that the money was borrowed and the final payments on the debt were not made until 2015. When in 2015 a tweet from the British Treasury revealed this surprising fact, there was a paroxysm of outrage as if slaveholders were still being paid off. I see the compensation in much more positive terms.

Of course, in an ideal world, compensation would have been paid to the slaves, not the slaveowners. Every man has a property in his own person and it was the slaves who had had their property stolen. In an ideal world, however, slavery would never have happened. Thus, the question the British abolitionists faced is not what happens in an ideal world but how do we get from where we are to a better world? Compensating the slaveowners was the only practical and peaceful way to get to a better world. As the great abolitionist William Wilberforce said on his deathbed “Thank God that I should have lived to witness a day in which England is willing to give twenty millions sterling for the abolition of slavery!”

The 1833 Slavery Abolition Act was preceded by the 1807 Slave Trade Act which had banned trade in slaves. In an excellent new paper, The long campaign: Britain’s fight to end the slave trade, economist historians Yi Jie Gwee and Hui Ren Tan assemble new archival data to assess how the Royal Navy’s anti slave-trade patrols expanded over time, how effective they were at curtailing the trade, the influence of supply-side enforcement versus demand-side changes on ending the trade, and why Britain persisted with this costly campaign.

Britain’s naval suppression campaign began on a modest scale but the campaign grew in strength throughout the 19th century, peaking in the late 1840s to early 1850s when over 14% of the entire Royal Navy fleet was deployed to anti-slavery patrols. The British patrols captured some 1,600 ships and freed some 150,000 people destined for slavery but they were at best only modestly successful at reducing the slave trade. The big impact came when Brazil, the largest remaining market for enslaved labor (by the mid-19th century, nearly 80% of trans-Atlantic slave voyages sailed under Brazilian or Portuguese flags), enacted its anti slave-trade law in 1850. Britain’s campaign was not without influence on the demand side however as passage of the Aberdeen Act in 1845 allowed the Royal Navy to seize Brazilian slave ships and that put pressure on Brazil and helped spur the 1850 law.

The suppression patrols were expensive (consuming ships, men, and funds), and Britain derived no direct economic benefit from them. Yet, even during the Napoleonic Wars, the Opium Wars, and the Crimean War, the Royal Navy continued to station ships, even high-tech steam ships, off West Africa to catch slavers. Due to the expense, the patrols were controversial and there were attempts to end them. Gwee and Tan look at the votes on ending the patrols and find that ideology was the dominant factor explaining support for the patrols, that is a principled opposition to the slave trade and a belief in the moral cause of abolition kept Britain in the war against slavery even at considerable expense.

Ordinarily, I teach politics without romance and look for interest as an explanation of political action and while I don’t doubt that doing good and doing well were correlated, even during abolition, I also agree with Gwee and Tan that the British war on slavery was primarily driven by ideology and moral principle as both the compensation plan and the support of the anti-slavery patrols attest.

British taxpayers shouldered an enormous military and financial burden to eliminate slavery, reflecting a generosity of spirit and a sincere attempt to address a moral wrong—an act of atonement that stands as one of the most unusual and significant in history.

What the financial regulators are saying and feeling

1. “Yes, we know stablecoins will have one hundred percent reserves, but we are not sure we can regulate that system into a position of safety.”

2. “Well, the rest of the financial system has nothing like one hundred percent reserves, but don’t worry we have everything there under control.”

The hole is large enough to drive a truck through. Keep this contrast in mind, because you will be hearing it, expressed in other terms of course, hundreds of times over the next year or so.

They solved for the Kansas City Chiefs enforcement equilibrium

We examine how financial pressure influences rule enforcement by leveraging a novel setting: NFL officiating. Unlike traditional regulatory environments, NFL officiating decisions are immediate, transparent, and publicly scrutinized, providing a unique empirical lens to test whether a worsening financial climate shapes enforcement behavior. Analyzing 13,136 defensive penalties from 2015 to 2023, we find that postseason officiating disproportionately favors the Mahomes-era Kansas City Chiefs, coinciding with the team’s emergence as a key driver of TV viewership/ratings and, thereby, revenue. Our study suggests that financial reliance on dominant entities can alter enforcement dynamics, a concern with implications far beyond sports governance.

That is from a new piece by Spencer Barnes, Ted Dischman, and Brandon Mendez. Via the excellent Kevin Lewis.

Sentences to ponder

By ordering the U.S. military to summarily kill a group of people aboard what he said was a drug-smuggling boat, President Trump used the military in a way that had no clear legal precedent or basis, according to specialists in the laws of war and executive power.

Mr. Trump is claiming the power to shift maritime counterdrug efforts from law enforcement rules to wartime rules. The police arrest criminal suspects for prosecution and cannot instead simply gun suspects down, except in rare circumstances where they pose an imminent threat to someone.

Here is more from the NYT.

The polity that is Brazil

Yet perhaps the biggest reason spending is high is that the constitution requires it. The charter mandates an extraordinary 90% of all federal spending. Notably it ties most public pensions to wage growth, and requires health and education spending to rise in line with revenue growth. If Brazil were to end most tax exemptions and undo these two policies, its debt-to-gdp ratio, which is already above 90%, would be almost 20 percentage points lower by 2034 than it would be without any reform, reckons the IMF. To deal with all this, what is really needed is to amend the constitution.

High spending and a tangle of subsidised credit schemes also reduce the effectiveness of monetary policy. That means the central bank must increase rates even higher to control inflation. Brazil’s real interest rate of 10% is among the highest in the world. Such rates cripple investment and drag down growth, while well-connected businessmen can get their hands on artificially cheap rates.

Among those who must pay the full rate is the government itself.

And:

Tax exemptions total 7% of gdp, up from 2% in 2003 (see chart 2). Dozens of sectors receive tax breaks or credit subsidies on the basis that they are national champions, or from “temporary” help that has never ended. Brazil’s courts cost 1.3% of gdp, making them the second-most expensive in the world, with much of that going on cushy pensions and perks. Some $15bn a year, or 78% of the military budget, is spent on pensions and salaries. The United States spends just one-quarter of the defence budget on personnel.

Here is more from The Economist.

Inside India’s endless trials

The FT’s Krishn Kaushik covers the courts in India:

…in one recent example a Delhi court concluded a property dispute after 66 years. Both the original litigants were dead. Still, the lawyer for one of the warring parties cautioned that the conclusion was in fact not the end, as the ruling would be appealed.

Three years ago, after pondering a dispute for 16 years, the supreme court sent back a 60-year-old land case for fresh adjudication to a lower court, which had already taken over 30 years to give its judgment in 2006.

A 2021 study [excellent study, AT] of Mumbai real estate found that more than a quarter of the projects under planning or construction and 43 per cent of all “built-up spaces” in the city were under some litigation. My apartment block was one of them.

…One of the reasons for this accumulation is human resources. India has around 16 judges per million people, compared to over 150 for the US. In 2016, the issue brought the country’s chief justice, TS Thakur, to tears during a speech as he requested that the government hire more judges to wade through the “avalanche” of backlog.

Reminds me of one of my favorite MR posts, A Twisted Tale of Rent Control in the Maximum City.

*Adolescence*

This is a British TV show, in four episodes, available on Netflix. It is the first TV show I have wanted to watch in about four years. I cannot review it without immediate spoilers, but I can tell you it takes place in a school, in a criminal justice system, and in a family. Northern England, so do turn on those subtitles. Here are some reviews.

Philosophy of freedom podcast with philosopher Rebecca Lowe

Here is the audio and transcript. Here is one excerpt:

Tyler: I think there are many notions of freedom, more than just three, but positive and negative are by far the most important. And they’re the ones you can at least try to build into political systems. A greater number of people understand what you’re talking about. And if you can manage to take care of those two in a reasonably satisfactory manner, odds are you’ve just succeeded. And I wouldn’t be too fussy about the others.

But I bet if you sat down, you could come up with 57 different kinds of freedom that are relevant. Look at Amartya Sen’s Paretian liberal paradox. Well, what would you choose if the choice affected only you? For him, that’s a significant part of liberty. I think it’s an insignificant part, but if he insists on putting it on his list, okay, it can go on the list.

And:

Rebecca: So when you talk about positive freedom, I think maybe what you’re talking about is something like an agent-focused framing of freedom. So I think one of the problems with the kind of negative framings generally, so if we think about the classic, particularly on the kind of liberal/libertarian side, people might want to say something like freedom is non-interference, freedom is non-coercion. The republicans might say it’s non-domination.

One risk with these things is I think it avoids centring the person who it is who’s doing the free thing, the person who has freedom, the agent. Is that fair?

Lots of lengthy threads and back and forth, so not so easy to excerpt. This podcast was almost entirely fresh material, and of course it is recommended.

We also decided to leave in the post-podcast discussion of the podcast itself. A good practice which should spread more widely, here is part of that:

TYLER

Let me give you a sense of where I think we’ve arrived at, and tell me if you agree. See if this is some kind of constructive progress. You want to defend societies based on freedom with some kind of metaphysics and you want to build up that metaphysics. I want to defend societies based on freedom, which are roughly the same societies as you want to defend, with a minimum of metaphysics. I’m always trying to push the metaphysics out the door. So a lot of this conversation has been Rebecca drags in the metaphysics…

REBECCA

This is my life! You know this!

TYLER

… and then Tyler… the baseball is thrown at him, he sort of quickly has it in his hands, and then tosses it to the other side of the room. Metaphysics, get away! And then Rebecca is frustrated because the metaphysics are gone and she throws more metaphysics at him. And that’s what we’ve been doing. Is that a fair characterisation of, you know, the show so far, as they call it?

Here is Rebecca’s Substack and podcast more generally, the emphasis is on people doing philosophy.

Decker and KingoftheCoast on single payer health insurance

Here is the conclusion of the piece:

To reiterate, the key point in this piece is that high administrative costs in US healthcare are unlikely to represent “do-nothing waste.” Some of the purported costs are entirely fake. To include them in the possible savings of single payer shows either ignorance or dishonesty. Some of the costs are to prevent waste and fraud, which should be paid by Medicare now (although they are not). Of what is left, the cost of duplication pales in comparison to the plausible benefits of choice and competition in health insurance. When you put all of these together, the case for single-payer is nonexistent. A better system would be to subsidize those who are too poor to pay, scrap the government health insurance providers and the VA, remove the employer tax deduction, and allow providers to compete.

Here is the full piece, excellent work.

The history of American corporate nationalization

I wrote this passage some while ago, but never published the underlying project:

The American Constitution is hostile to nationalization at a fundamental level. The Fifth Amendment prohibits government “takings” without just compensation to the owners, and that is sometimes called the “takings clause.” Since the United States did not start off with a large number of state-owned enterprises, there is no simple and legal way for the country to get from here to there. Government nationalization of private companies would prove expensive, most of all to the government itself. More importantly, the strength of American corporate interests has taken away any possible pressures to eliminate or ignore this amendment.

The lack of interest in state-owned enterprises reflects some broader features of the United States, most of all a kind of messiness and pluralism of control. An extreme federalism has bred a large number of regulators at federal, state, and local levels, often with overlapping jurisdictions. Each level of government digs its claws into the regulatory morass, and not always for the better, but this preempts nationalization, which would centralize power and control in one level of government. That is not the American way.

A tradition of strong state-level regulation was built up during the mid- to late 19th century, when the federal government did not have the resources, the reach, or the scope to do much nationalizing. America developed some very large national commercial enterprises, such as the railroads, Bell (a phone company), and Western Union (a communications and wire service), which were quite large and far-ranging before the federal government itself had reached a mature size. At that time local government accounted for about half of all government spending in the country and the federal government had few powers of regulation. It wasn’t quite laissez-faire, but America could not rely on its federal government and this shaped the later evolution of the country. To handle these booming corporate entities, America created more state-level regulation of business than was typical for the other industrializing Western countries. That steered Americans away from nationalization as a means for distributing political benefits or disciplining corporations[1]

This policy decision to rely so much on multiple levels of federalistic regulation comes with a price. American failures in physical infrastructure have been the other side of the coin of American successes in business. A strong rule of law, combined with so many legal checks and balances and blocking points, has carved out a protected space for private American businesses. They can operate with relatively secure property rights. At the same time, those same laws and blocking points make it hard to get a lot of things built when a change in property rights is required, whether government or business or both are doing the building. The law is used to obstruct growth and change, and for NIMBYism — “Not In My Backward,” and more generally for giving any litigation-ready interest group a voice in any decision it cares about. Can you imagine a sentence like this being written about China?: “The [New York and New Jersey] Port Authority sent out letters inviting tribe representatives to join the environmental review project, inviting the Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma and the Sand Hills Nation of Nebraska.”[2]

In America background patriotism sustains a rule by general national consensus, and so the American government doesn’t need extensive state-owned companies to build or maintain political support through the creation of so many privileged insiders. The American paradox is this: the reliance on the law reflects a relatively strong and legitimate government, but the multiplication of that law renders government ineffective in a lot of practical matters, especially when it comes to the proverbial “getting things done,” a dimension where the Chinese government has been especially strong.

You should note that although the United States has not so many state-owned enterprises, the American government still has ways of expressing its will on business, or as the case may be, favoring one set of businesses over another. In these latter cases it can be said that American business is expressing its will over government through forms of crony capitalism, a concept which is spreading in both America and China.

The United States has evolved a subtle brand of corporatism and industrial policy that is mostly decentralized and also – this is an important point — relatively stable across shifts of political power. America uses its large country privileges to maintain access to world markets and to protect the property rights of its investors, usually without much regard for whether they are Democrats or Republicans. For instance the State Department works hard to maintain open world markets for films and other cultural goods and services. Toward this end America has used trade negotiations, diplomatic leverage, foreign aid, and also explicit arm-twisting, based on its military commitments to protect allied nations in Western Europe and East Asia. America already had successful entertainment producers, it just wanted to make sure they could earn more money abroad, and that is why the American government usually insists on open access for audiovisual products when it negotiates free trade treaties. Yet in these deals there is not much if any explicit favoritism for one movie or television studio over another, or for one political alliance over another. Democrats are disproportionately overrepresented in Hollywood, but Republican administrations protect the interests of the American entertainment sector nonetheless. It’s about the money and the jobs, not about shifting political coalitions. You’ll note that the independence from particular political coalitions gives the American business environment a particular stability and predictability, to its advantage internationally and otherwise.

[1] See Millward (2013, chapter nine, and p.222 on chartering powers).

[2] That is from Howard (2014, p.10).

Contemporary TC again: Let us hope that I was at least partially correct…