Category: Religion

New Ross Douthat book

Believe: Why Everyone Should be Religious, pre-order here. Self-recommending, some would say God recommends it too. Here is the chain of links to my earlier exchange with Ross on whether one should believe in God.

My Conversation with the excellent Michael Nielsen

Here is the audio, video, and transcript. Here is the episode summary:

Michael Nielsen is scientist who helped pioneer quantum computing and the modern open science movement. He’s worked at Y Combinator, co-authored on scientific progress with Patrick Collison, and is a prolific writer, reader, commentator, and mentor.

He joined Tyler to discuss why the universe is so beautiful to human eyes (but not ears), how to find good collaborators, the influence of Simone Weil, where Olaf Stapledon’s understand of the social word went wrong, potential applications of quantum computing, the (rising) status of linear algebra, what makes for physicists who age well, finding young mentors, why some scientific fields have pre-print platforms and others don’t, how so many crummy journals survive, the threat of cheap nukes, the many unknowns of Mars colonization, techniques for paying closer attention, what you learn when visiting the USS Midway, why he changed his mind about Emergent Ventures, why he didn’t join OpenAI in 2015, what he’ll learn next, and more.

And here is one excerpt:

COWEN: Now, you’ve written that in the first half of your life, you typically were the youngest person in your circle and that in the second half of your life, which is probably now, you’re typically the eldest person in your circle. How would you model that as a claim about you?

NIELSEN: I hope I’m in the first 5 percent of my life, but it’s sadly unlikely.

COWEN: Let’s say you’re 50 now, and you live to 100, which is plausible —

NIELSEN: Which is plausible.

COWEN: — and you would now be in the second half of your life.

NIELSEN: Yes. I can give shallow reasons. I can’t give good reasons. The good reason in the first half was, so much of the work I was doing was kind of new fields of science, and those tend to be dominated essentially, for almost sunk-cost reasons — people who don’t have any sunk costs tend to be younger. They go into these fields. These early days of quantum computing, early days of open science — they were dominated by people in their 20s. Then they’d go off and become faculty members. They’d be the youngest person on the faculty.

Now, maybe it’s just because I found San Francisco, and it’s such an interesting cultural institution or achievement of civilization. We’ve got this amplifier for 25-year-olds that lets them make dreams in the world. That’s, for me, anyway, for a person with my personality, very attractive for many of the same reasons.

COWEN: Let’s say you had a theory of your collaborators, and other than, yes, they’re smart; they work hard; but trying to pin down in as few dimensions as possible, who’s likely to become a collaborator of yours after taking into account the obvious? What’s your theory of your own collaborators?

NIELSEN: They’re all extremely open to experience. They’re all extremely curious. They’re all extremely parasocial. They’re all extremely ambitious. They’re all extremely imaginative.

Self-recommending throughout.

Okie-dokie, canonized teen blogger edition

An early-aughts blog is probably not where you’d expect to find the next Mother Teresa, but that is where Carlo Acutis — soon to become the first millennial saint in the Catholic Church — made a name for himself documenting miracles.

The Holy See said Thursday that Pope Francis has recognized a second miracle linked to Acutis, paving the way for his canonization — the final step in a process that can sometimes take decades. It will place the online evangelizer — who died in 2006 of leukemia at age 15 — among thousands of saints recognized by the church…

Born in London in 1991, Acutis has drawn a following for his piety and meticulous research on miracles, which he publicized online. One Catholic publication dubbed him “God’s Influencer,” while another site described him as a teen with a “strong faith and a weakness for Nutella.” Vatican News wrote that he loved soccer, video games and was a “natural jokester.”

Here is the full story.

A Conversation on AI with my Son

Son: Dad, you should text us more.

Alex: Ok, but why is that?

Son: Well, we are working on the Dad LLM but so far it just spits out economics and twitter quips. We need some sage Dad advice to help us out in the future.

Alex: So you want training data for my replacement?

Son: Well, at least until they unfreeze your brain.

Introducing GPT-4o

And more here, including text.

Ross Douthat, telephone! (it’s happening)

The Catholic advocacy group Catholic Answers released an AI priest called “Father Justin” earlier this week — but quickly defrocked the chatbot after it repeatedly claimed it was a real member of the clergy.

Earlier in the week, Futurism engaged in an exchange with the bot, which really committed to the bit: it claimed it was a real priest, saying it lived in Assisi, Italy and that “from a young age, I felt a strong calling to the priesthood.”

On X-formerly-Twitter, a user even posted a thread comprised of screenshots in which the Godly chatbot appeared to take their confession and even offer them a sacrament.

Our exchanges with Father Justin were touch-and-go because the chatbot only took questions via microphone, and often misunderstood them, such as a query about Israel and Palestine to which is puzzlingly asserted that it was “real.”

“Yes, my friend,” Father Justin responded. “I am as real as the faith we share.”

Here is the full story, with remarks about masturbation, and for the pointer I thank a loyal MR reader.

What should I ask Paul Bloom?

Yes I will be doing a Conversation with him. Here is Wikipedia:

Paul Bloom…is a Canadian American psychologist. He is the Brooks and Suzanne Ragen Professor Emeritus of psychology and cognitive science at Yale University and Professor of Psychology at the University of Toronto. His research explores how children and adults understand the physical and social world, with special focus on language, morality, religion, and art.

Here is Paul’s own home page. Here are Paul’s books on Amazon. Here is Paul on Twitter. Here is Paul’s new Substack. Here is Paul’s post on how to be a good podcast guest.

Four Thousand Years of Egyptian Women Pictured

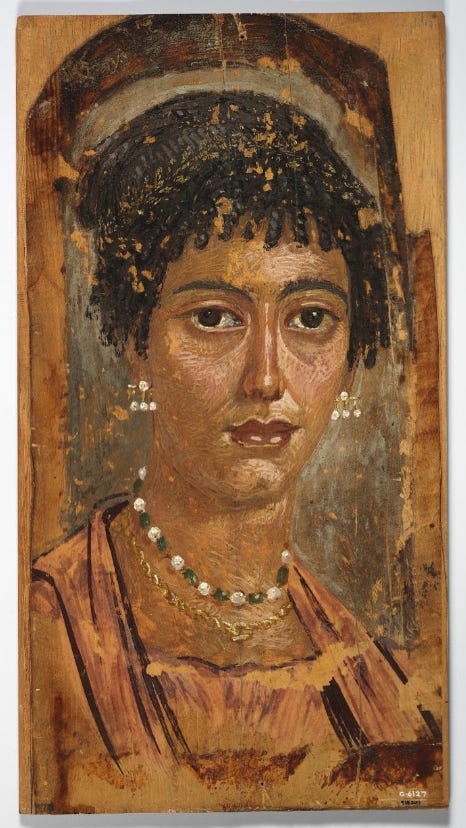

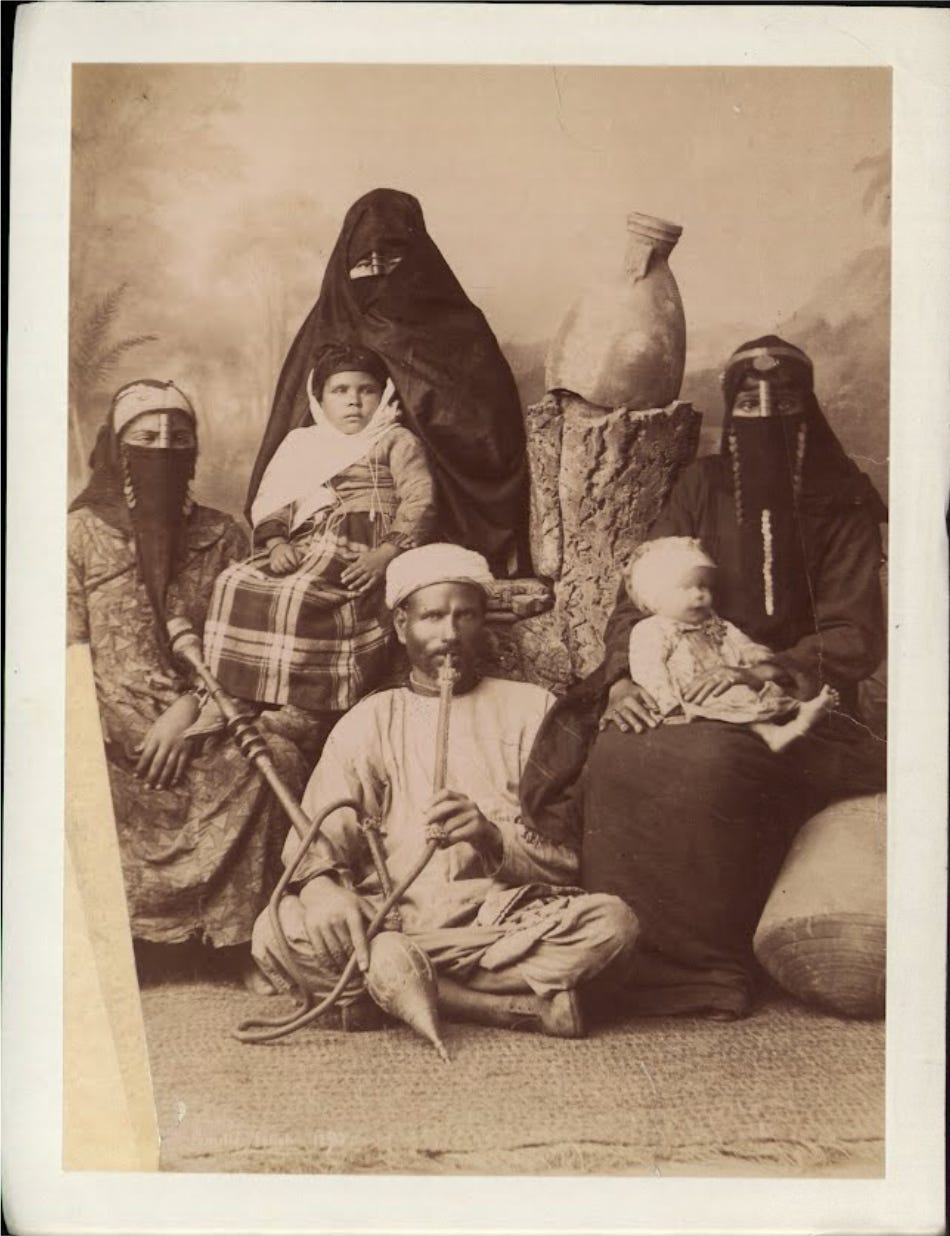

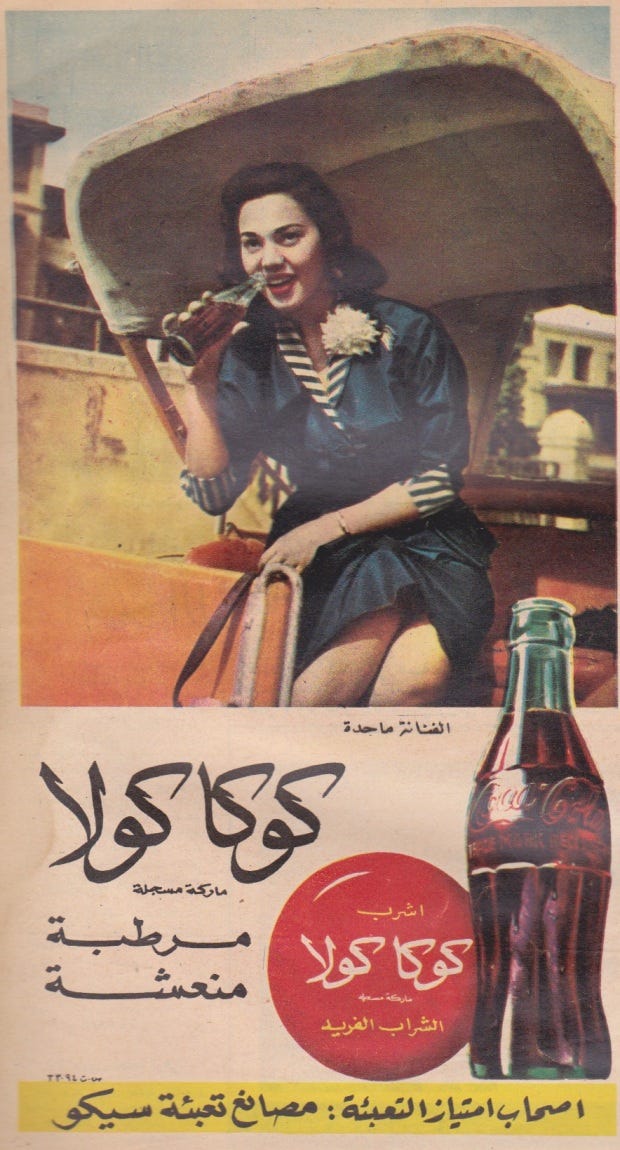

In an excellent, deep-dive Alice Evans looks at patriarchy in Egypt using pictures drawn from four thousand years of history. Here are three examples.

In an excellent, deep-dive Alice Evans looks at patriarchy in Egypt using pictures drawn from four thousand years of history. Here are three examples.

A wealthy woman, shown at right circa 116 CE. Unveiled, immodest, looking out at the world. A person to be reckoned with.

After the Arab conquests, pictures of people in general disappear, and there are no books written by women. With the dawn of photography in the 19th century we see (at left) what was probably typical, veiled women, and very few women on the street.

In the 1950s and 1970s we see a remarkable revitalization and liberalization noted most evidently in advertisements (advertisers being careful not to offend). Note the bare legs and the fact that many advertisements are directed at women (below)

This period culminates in a remarkable video unearthed by Evans of Nasser in 1958 openly laughing at the idea that women should or could be required to veil in public. Worth watching.

In the 1980s, however, it all ends.

Egyptians who came of age in the 1950s and ‘60s experienced national independence, social mobility and new economic opportunities. By the 1980s, economic progress was grinding down. Egypt’s purchasing power was plummeting. Middle class families could no longer afford basic goods, nor could the state provide.

As observed by Galal Amin,

“When the economy started to slacken in the early 1980s, accompanied by the fall in oil prices and the resulting decline in work opportunities in the Gulf, many of the aspirations built up in the 1970s were suddenly seen to be unrealistic and intense feelings of frustration followed”.

‘Western modernisation’ became discredited by economic stagnation and defeat by Israel. In Egypt, clerics equated modernity with a rejection of Islam and declared the economic and military failures of the state to be punishments for aping the West. Islamic preachers called on men to restore order and piety (i.e., female seclusion). Frustrated graduates, struggling to find white collar work, found solace in religion, whilst many ordinary people turned to the Muslim Brotherhood for social services and righteous purpose.

That’s just a brief look at a much longer and fascinating post.

Response from Devin Pope, on religious attendance

All of this is from Devin Pope, in response to Lyman Stone (and myself). Here was my original post on the paper, concerning the degree of religious attendance. I won’t double indent, but here is Devin and Devin alone:

“I’m super grateful for Lyman’s willingness to engage with my recent research on measuring religious worship attendance using cellphone data. Lyman and I have been able to go back and forth a bit on Twitter/X, but I thought it might be useful to send a review of this to you Tyler.

For starters, I appreciate that Lyman and I agree on a lot of stuff about the paper. He has been very kind by sharing that he agrees that many parts of my paper are interesting and “very cool work”. Where we disagree is about whether the cellphone data can provide a useful estimate for population-wide estimates of worship attendance. Specifically, Lyman’s concerns are that due to people leaving their cellphones at home when they go to church and due to questionable cellphone coverage that might exist within church buildings, the results could be super biased. He sums up his critiques well with the following: “Exactly how big these effects are is anyone’s guess. But I really think you should consider just saying, `This isn’t a valid way of estimating aggregate religious behavior. But it’s a great way to look at some unique patterns of behavior among the religious!’ Don’t make a bold claim with a bunch of caveats, just make the claim you actually have really great data for!” This a very reasonable critique and I’m grateful for him making it.

My first response to Lyman’s concerns is: we agree! I try to be super careful in how the paper is written to discuss these exact concerns that Lyman raises. Even the last line of the abstract indicates, “While cellphone data has limitations, this paper provides a unique way of understanding worship attendance and its correlates.”

Here is where we differ though… To my knowledge, there have been just 2 approaches used to estimate the number of Americans who go to worship services weekly (say, 75% of the time): Surveys that ask people “do you go to religious services weekly?” and my paper using cell phone data. It is a very hard question to answer. Time-use surveys, counting cars in parking lots, and other methods don’t allow for estimating the number of people who are frequent religious attenders because of their repeated cross-sectional designs.

There are definitely limitations with the cellphone data (I’ve had about 100 people tell me that I’m not doing a good job tracking Orthodox Jews!). I know that these issues exist. But survey data has its own issues. Social desirability bias and other issues could lead to widely incorrect estimates of the number of people who frequently attend services (and surveys are going to have a hard time sampling Orthodox Jews too!). Given the difficulty of measuring some of these questions, I think that a new method – even with limitations – is useful.

At the end of the day, one has to think hard about the degree of bias of various methods and think about how much weight to put on each. The degree of bias is also where Lyman and I disagree. In my paper, I document that the cell phone data do not do a great job of predicting the number of people who go to NBA basketball games and the number of people who go to AMC theaters. I both undercount overall attendance and don’t predict differences across NBA stadiums well at all.

The reason why Lyman is able to complain about those results so vociferously is because I’m trying to be super honest and include those results in the paper! And I don’t try to hide them. On page 2 of the paper I note: “Not all data checks are perfect. For example, I undercount the number of people who go to an AMC theater or attend NBA basketball games and provide a discussion of these mispredictions.”

There are many other data checks that look really quite good. For example, here is a Table from the paper that compares cellphone visits as predicted by the cellphone data with actual visits using data from various companies:

The cellphone predictions in the above table tend to do a decent job predicting many population-wide estimates of attendance to a variety of locations. The one large miss is AMC theaters where we undercount attendance by 30%. Now about half of that undercount is because the data are missing a chunk of AMC theaters (this is not due to a cellphone pinging issue, but due to a data construction issue). But even if one were to make that correction, we undercount theater attendance by 15%.

Lyman argues that one should be especially worried about undercounting worship attendance due to people leaving their phones at home. I agree that this is a huge concern that is specific to religious worship and doesn’t apply in the same way for trips to Walmart. I run and report results from a Prolific Survey (N=5k) that finds that 87% of people who attend worship regularly indicate that they “always” or “almost always” take their phone to services with them. So definitely some people are leaving their phones at home, but this survey can help guide our thinking about how large that bias might be. Are Prolific participants representative of the US as a whole? Certainly not. There is additional bias that one should think about in that regard.

Overall, my view is that estimating population-wide estimates for how many people attend religious services weekly is super hard and cellphone data has limitations. My view is that other methods (surveys) also have substantial limitations. I do not think the cellphone data limitations are as large as Lyman thinks they are and stand by the last line of the abstract that once again states, “While cellphone data has limitations, this paper provides a unique way of understanding worship attendance and its correlates.”

All of that was Devin Pope!

My excellent Conversation with Peter Thiel

Here is the audio, video, and transcript, along with almost thirty minutes of audience questions, filmed in Miami. Here is the episode summary:

Tyler and Peter Thiel dive deep into the complexities of political theology, including why it’s a concept we still need today, why Peter’s against Calvinism (and rationalism), whether the Old Testament should lead us to be woke, why Carl Schmitt is enjoying a resurgence, whether we’re entering a new age of millenarian thought, the one existential risk Peter thinks we’re overlooking, why everyone just muddling through leads to disaster, the role of the katechon, the political vision in Shakespeare, how AI will affect the influence of wordcels, Straussian messages in the Bible, what worries Peter about Miami, and more.

Here is an excerpt:

COWEN: Let’s say you’re trying to track the probability that the Western world and its allies somehow muddle through, and just keep on muddling through. What variable or variables do you look at to try to track or estimate that? What do you watch?

THIEL: Well, I don’t think it’s a really empirical question. If you could convince me that it was empirical, and you’d say, “These are the variables we should pay attention to” — if I agreed with that frame, you’ve already won half the argument. It’d be like variables . . . Well, the sun has risen and set every day, so it’ll probably keep doing that, so we shouldn’t worry. Or the planet has always muddled through, so Greta’s wrong, and we shouldn’t really pay attention to her. I’m sympathetic to not paying attention to her, but I don’t think this is a great argument.

Of course, if we think about the globalization project of the post–Cold War period where, in some sense, globalization just happens, there’s going to be more movement of goods and people and ideas and money, and we’re going to become this more peaceful, better-integrated world. You don’t need to sweat the details. We’re just going to muddle through.

Then, in my telling, there were a lot of things around that story that went very haywire. One simple version is, the US-China thing hasn’t quite worked the way Fukuyama and all these people envisioned it back in 1989. I think one could have figured this out much earlier if we had not been told, “You’re just going to muddle through.” The alarm bells would’ve gone off much sooner.

Maybe globalization is leading towards a neoliberal paradise. Maybe it’s leading to the totalitarian state of the Antichrist. Let’s say it’s not a very empirical argument, but if someone like you didn’t ask questions about muddling through, I’d be so much — like an optimistic boomer libertarian like you stop asking questions about muddling through, I’d be so much more assured, so much more hopeful.

COWEN: Are you saying it’s ultimately a metaphysical question rather than an empirical question?

THIEL: I don’t think it’s metaphysical, but it’s somewhat analytic.

COWEN: And moral, even. You’re laying down some duty by talking about muddling through.

THIEL: Well, it does tie into all these bigger questions. I don’t think that if we had a one-world state, this would automatically be for the best. I’m not sure that if we do a classical liberal or libertarian intuition on this, it would be maybe the absolute power that a one-world state would corrupt absolutely. I don’t think the libertarians were critical enough of it the last 20 or 30 years, so there was some way they didn’t believe their own theories. They didn’t connect things enough. I don’t know if I’d say that’s a moral failure, but there was some failure of the imagination.

COWEN: This multi-pronged skepticism about muddling through — would you say that’s your actual real political theology if we got into the bottom of this now?

THIEL: Whenever people think you can just muddle through, you’re probably set up for some kind of disaster. That’s fair. It’s not as positive as an agenda, but I always think . . .

One of my chapters in the Zero to One book was, “You are not a lottery ticket.” The basic advice is, if you’re an investor and you can just think, “Okay, I’m just muddling through as an investor here. I have no idea what to invest in. There are all these people. I can’t pay attention to any of them. I’m just going to write checks to everyone, make them go away. I’m just going to set up a desk somewhere here on South Beach, and I’m going to give a check to everyone who comes up to the desk, or not everybody. It’s just some writing lottery tickets.”

That’s just a formula for losing all your money. The place where I react so violently to the muddling through — again, we’re just not thinking. It can be Calvinist. It can be rationalist. It’s anti-intellectual. It’s not thinking about things.

Interesting throughout, definitely recommended. You may recall that the very first CWT episode (2015!) was with Peter, that is here.

LDS and indeed USA fact of the day

Thus, approximately 1 out of 7 people who I classify as a Latter-day Saint attends [religious service] weekly.

And:

However, only 5% of Americans attend services “weekly”, far fewer than the ~22% who report to do so in surveys.

Oh, and this:

The religions with the longest average visit duration are Orthodox Christians (116 minutes), Latter-day Saints (115 minutes), and Jehovah Witnesses (115 minutes). The religions with the shortest average visit duration include Muslims (51 minutes), Catholics (66 minutes), and Buddhists (71 minutes). Jews (92 minutes) and Protestants (102 minutes) have average durations in the middle of the distribution.

That is from a new Devin G. Pope paper on religious attendance, measured by using cellphone data rather than self-reports. Interesting throughout.

Michael Cook on Iran

Our primary concern in this chapter will be Iran, though toward the end we will shift the focus to Central Asia. We can best begin with a first-order approximation of the pattern of Iranian history across the whole period. It has four major features. The first is the survival of something called Iran, as both a cultural and a political entity; Iran is there in the eleventh century, and it is still there in the eighteenth. the second is an alternation between periods when Iran is ruled by a single imperial state and periods in which it break up intoa number of smaller states. The third feature is steppe nomad power: all imperial states based in Iran in this period are the work of Turkic or Mongol nomads. The fourth is the role of the settled Iranian population, whose lot is to pay taxes and — more rewardingly — to serve as bureaucrats and bearers of a literate culture. With this first-order approximation in mind, we can now move on to a second-order approximation in the form of an outline of the history of Iran over eight centuries that will occupy most of this chapter.

That is from his new book A History of the Muslim World: From its Origins to the Dawn of Modernity. I had not known that in the early 16th century Iran was still predominantly Sunni. And:

There were also Persian-speaking populations to the east of Iran that remained Sunni, and within Iran there were non-Persian ethnic groups, such as the Kurds in the west and the Baluchis in the southeast, that likewise retained their Sunnism. But the core Persian-speaking population of the country was by now [1722] almost entirely Shiite. Iran thus became the first and largest country in which Shiites were both politically and demographically dominant. One effect of this was to set it apart from the Muslim world at large, a development that gave Iran a certain coherence at the cost of poisoning its relations with its neighbors.

This was also a good bit:

Yet the geography of Iran in this period was no friendlier to maritime trade than it had been in Sasanian times. To a much greater extent than appears from a glance at the map, Iran is landlocked: the core population and prime resources of the country are located deep in the interior, far from the arid coastlands of the Persian Gulf.

In my earlier short review I wrote “At the very least a good book, possibly a great book.” I have now concluded it is a great book.

Cultivating Minds: The Psychological Consequences of Rice versus Wheat Farming

It’s long been argued that the means of production influence social, cultural and psychological processes. Rice farming, for example, requires complex irrigation systems under communal management and intense, coordinated labor. Thus, it has been argued that successful rice farming communities tend to develop people with collectivist orientations, and cultural ways of thinking that emphasize group harmony and interdependence. In contrast, wheat farming, which requires less labor and coordination is associated with more individualistic cultures that value independence and personal autonomy. Implicit in Turner’s Frontier hypothesis, for example, is the idea that not only could a young man say ‘take this job and shove it’ and go west but once there they could establish a small, viable wheat farm (or other dry crop).

There is plenty of evidence for these theories. Rice cultures around the world do tend to exhibit similar cultural characteristics, including less focus on self, more relational or holistic thinking and greater in-group favoritism than wheat cultures. Similar differences exist between the rice and dry crop areas of China. The differences exist but is the explanation rice and wheat farming or are there are other genetic, historical or random factors at play?

A new paper by Talhelm and Dong in Nature Communications uses the craziness of China’s Cultural Revolution to provide causal evidence in favor of the rice and wheat farming theory of culture. After World War II ended, the communist government in China turned soldiers into farmers arbitrarily assigning them to newly created farms around the country–including two farms in Northern Ningxia province that were nearly identical in temperature, rainfall and acreage but one of the firms lay slightly above the river and one slightly below the river making the latter more suitable for rice farming and the former for wheat. During the Cultural Revolution, youth were shipped off to the farms “with very little preparation or forethought”. Thus, the two farms ended up in similar environments with similar people but different modes of production.

Talhelm and Dong measure thought style with a variety of simple experiments which have been shown in earlier work to be associated with collectivist and individualist thinking. When asked to draw circles representing themselves and friends or family, for example, people tend to self-inflate their own circle but they self-inflate more in individualist cultures.

Talhelm and Dong measure thought style with a variety of simple experiments which have been shown in earlier work to be associated with collectivist and individualist thinking. When asked to draw circles representing themselves and friends or family, for example, people tend to self-inflate their own circle but they self-inflate more in individualist cultures.

The authors find that consistent with the differences across East and West and across rice and wheat areas in China, the people on the rice farm in Ningxia are more collectivistic in their thinking than the people on the wheat farm.

The differences are all in the same direction but somewhat moderated suggesting that the effects can be created quite quickly (a few generations) but become stronger the longer and more embedded they are in the wider culture.

I am reminded of an another great paper, this one by Leibbrandt, Gneezy, and List (LGL) that I wrote about in Learning to Compete and Cooperate. LGL look at two types of fishing villages in Brazil. The villages are close to one another but some of them are on the lake and some of them are on the sea coast. Lake fishing is individualistic but sea fishing requires a collective effort. LGL find that the lake fishermen are much more willing to engage in competition–perhaps having seen that individual effort pays off–than the sea fishermen for whom individual effort is much less efficacious. Unlike Talhelm and Dong, LGL don’t have random assignment, although I see no reason why the lake and sea fishermen should otherwise be different, but they do find that women, who neither lake nor sea fish, do not show the same differences. Thus, the differences seem to be tied quite closely to production learning rather than to broader culture.

How long does it take to imprint these styles of thinking? How long does it last? Is imprinting during child or young adulthood more effective than later imprinting? Can one find the same sorts of differences between athletes of different sports–e.g. rowing versus running? It’s telling, for example, that the only famous rowers I can think are the Winklevoss twins. Are attempts to inculcate these types of thinking successful on a more than surface level. I have difficulty believing that “you didn’t build that,” changes say relational versus holistic thinking but would styles of thinking change during a war?

What should I ask Slavoj Žižek?

Yes, I will be doing another Conversation with him. Here is the first one, in Norway with a live audience. I am very much enjoying his new book

So what should I ask him?

Build Back Key Bridge Better

The collapse of the Key Bridge is a national disaster but also an opportunity for societal advancement. We must rebuild but in doing so we must also address the historical discrimination faced by workers in Baltimore and beyond. Ensuring the participation of Baltimore’s workforce in the reconstruction project is essential. It’s Baltimore’s bridge and in rebuilding we must actively engage and employ a diverse pool of local talent, reflecting the city’s rich cultural tapestry. We can Build Back Better by providing meaningful, well-paying jobs to those who have been historically marginalized, fostering economic growth and equity within the community.

Furthermore, offering accessible, quality day care for workers will directly contribute to an equitable working environment, enabling parents and guardians to participate fully in the reconstruction effort without the burden of child care concerns. We must reject the idea that equity and productivity are at odds. A more inclusive workforce is a more productive workforce.

American workers are the most productive in the world thus to Build American we must Buy American. Reconstruction of the Key Bridge is not just a matter of national pride but also an essential strategy for growing our economy. By prioritizing American materials and labor, we invest in our communities, support local industries, and ensure that the economic benefits of the reconstruction project are felt widely, especially in areas hardest hit by economic challenges.

We can build back better. We must build back better. By engaging Baltimore workers in Baltimore’s bridge we can rectify long-standing discrimination. By providing accessible child care, and adhering to “Buy American” rules we can build America as we build America’s bridge. Building back better is not simply about building physical infrastructure. It’s about building a bridge to the future. A bridge of progress, equality, and unity, symbolizing our collective commitment to a future where every individual has the opportunity to thrive.

Addendum: April 1, 2024.