What should I ask Jimmy Wales?

Yes I will be doing a Conversation with him. Here is his uh…Wikipedia page. So what should I ask?

My podcast with The Economist

Here is the proper link.

Friday assorted links

1. Is Baghadad now a boomtown? (The Economist) And tourists are returning to Iraq to see ancient Babylon.

3. Claims.

5. Should the Germans stop teaching Goethe? (no)

6. Bob Cooter, RIP.

7. Nepal update.

Are we building an “animal internet”?

Should we?

Human owners of parrots in the study reported that the birds seemed happier when they could interact online with other parrots and not just with people…

Scientists are using digital technology to revolutionise animal communication and move towards an “animal internet”, using new products such as phones for dogs and touchscreens for parrots.

Experiments by Glasgow university have enabled several species, from parrots and monkeys to cats and dogs, to enjoy long-distance video and audio calls. They have also developed technology for monkeys and lemurs in zoos to trigger soothing sounds, smells or video images on demand.

Ilyena Hirskyj-Douglas, who heads the university’s Animal-Computer Interaction Group, started by developing a DogPhone that enables animals to contact their owners when they are left alone.

Her pet labrador Zack calls her by picking up and shaking an electronic ball containing an accelerometer. When this senses movement, it sets up a video call on a laptop, allowing Zack to interact with her whenever he chooses. She can also use the system to call him. Either party is free to pick up or ignore the call.

…When a parrot wanted to connect with a distant friend, a touchscreen showed a selection of other birds available online. The parrots learned to activate the screen, designed specially for them, by touching it gently with their tongues rather than pecking aggressively with their beaks.

“We had 26 birds involved,” said Hirskyj-Douglas. “They would use the system up to three hours a day, with each call lasting up to five minutes.” The interactions ranged from preening and playing with toys to loud vocal exchanges.

Here is more from Clive Cookson from the FT. Via Malinga.

The polity that is Albania

Albania has become the first country in the world to have an AI minister — not a minister for AI, but a virtual minister made of pixels and code and powered by artificial intelligence.

Her name is Diella, meaning sunshine in Albanian, and she will be responsible for all public procurement, Prime Minister Edi Rama said Thursday.

During the summer, Rama mused that one day the country could have a digital minister and even an AI prime minister, but few thought that day would come around so quickly.

Here is the full story, we will see how this develops. Diella also is tokenized. Via MN.

A new RCT on banning smartphones in the classroom

Widespread smartphone bans are being implemented in classrooms worldwide, yet their causal effects on student outcomes remain unclear. In a randomized controlled trial involving nearly 17,000 students, we find that mandatory in-class phone collection led to higher grades — particularly among lower-performing, first-year, and non-STEM students — with an average increase of 0.086 standard deviations. Importantly, students exposed to the ban were substantially more supportive of phone-use restrictions, perceiving greater benefits from these policies and displaying reduced preferences for unrestricted access. This enhanced student receptivity to restrictive digital policies may create a self-reinforcing cycle, where positive firsthand experiences strengthen support for continued implementation. Despite a mild rise in reported fear of missing out, there were no significant changes in overall student well-being, academic motivation, digital usage, or experiences of online harassment. Random classroom spot checks revealed fewer instances of student chatter and disruptive behaviors, along with reduced phone usage and increased engagement among teachers in phone-ban classrooms, suggesting a classroom environment more conducive to learning. Spot checks also revealed that students appear more distracted, possibly due to withdrawal from habitual phone checking, yet, students did not report being more distracted. These results suggest that in-class phone bans represent a low-cost, effective policy to modestly improve academic outcomes, especially for vulnerable student groups, while enhancing student receptivity to digital policy interventions.

That is from a recent paper by Alp Sungu, Pradeep Kumar Choudhury, and Andreas Bjerre-Nielsen. Note with grades there is “an average increase of 0.086 standard deviations.” I have no problem with these policies, but it mystifies me why anyone would put them in their top five hundred priorities, or is that five thousand? Here is my earlier post on Norwegian smart phone bans, with comparable results.

That was then, this is now

My prediction from 2021:

If Russia and Belarus became a single political unit, there would be only a thin band of land, called the Suwalki Gap, connecting the Baltics to the rest of the European Union. Unfortunately, that same piece of territory would stand in the way of the new, larger Russia connecting with the now-cut off Russian region of Kaliningrad. Over the long term, could the Baltics maintain their independence? If not, the European Union would show it is entirely a toothless entity, unable to guarantee the sovereignty of its members.

Even if there were no formal political union between Russia and Belarus, the territorial continuity and integrity of the EU could soon be up for grabs. The EU has more at stake in an independent Belarus than it likes to admit.

Here is the Bloomberg column from that time. I had always thought such an altercation would occur before Russia moved on Ukraine, but of course that prediction turned out to be wrong. My view was that Putin would first seek to weaken NATO, and Ukraine would be closer to the end of the menu than the beginning. In any case, I have been saying to some friends lately that, in history, the Trump presidency will (that is will, not should) be judged by how he handles the eastern European “situation.” Do note by the way that the recent Russian drones were launched from Belarus.

Thursday assorted links

The British War on Slavery

In August of 1833 the British passed legislation abolishing slavery within the British Empire and putting more than 800,000 enslaved Africans on the path to freedom. To make this possible, the British government paid a huge sum, £20 million or about 5% of GDP at the time, to compensate/bribe the slaveowners into accepting the deal. In inflation adjusted terms this is about £2.5 billion today (2025) but relative to GDP the British spent an equivalent of about $170 billion to free the slaves, a very large expenditure.

Indeed, the expenditure was so large that the money was borrowed and the final payments on the debt were not made until 2015. When in 2015 a tweet from the British Treasury revealed this surprising fact, there was a paroxysm of outrage as if slaveholders were still being paid off. I see the compensation in much more positive terms.

Of course, in an ideal world, compensation would have been paid to the slaves, not the slaveowners. Every man has a property in his own person and it was the slaves who had had their property stolen. In an ideal world, however, slavery would never have happened. Thus, the question the British abolitionists faced is not what happens in an ideal world but how do we get from where we are to a better world? Compensating the slaveowners was the only practical and peaceful way to get to a better world. As the great abolitionist William Wilberforce said on his deathbed “Thank God that I should have lived to witness a day in which England is willing to give twenty millions sterling for the abolition of slavery!”

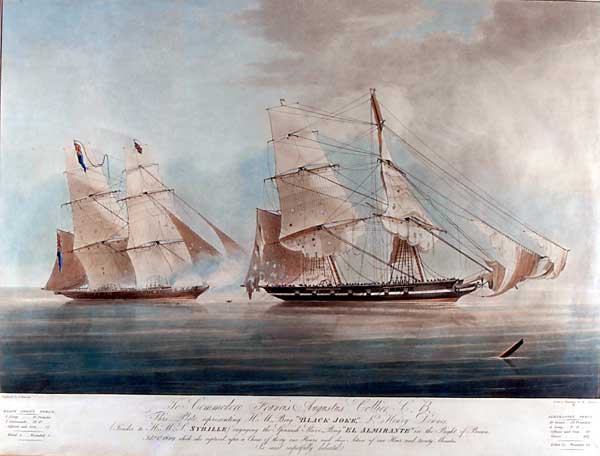

The 1833 Slavery Abolition Act was preceded by the 1807 Slave Trade Act which had banned trade in slaves. In an excellent new paper, The long campaign: Britain’s fight to end the slave trade, economist historians Yi Jie Gwee and Hui Ren Tan assemble new archival data to assess how the Royal Navy’s anti slave-trade patrols expanded over time, how effective they were at curtailing the trade, the influence of supply-side enforcement versus demand-side changes on ending the trade, and why Britain persisted with this costly campaign.

Britain’s naval suppression campaign began on a modest scale but the campaign grew in strength throughout the 19th century, peaking in the late 1840s to early 1850s when over 14% of the entire Royal Navy fleet was deployed to anti-slavery patrols. The British patrols captured some 1,600 ships and freed some 150,000 people destined for slavery but they were at best only modestly successful at reducing the slave trade. The big impact came when Brazil, the largest remaining market for enslaved labor (by the mid-19th century, nearly 80% of trans-Atlantic slave voyages sailed under Brazilian or Portuguese flags), enacted its anti slave-trade law in 1850. Britain’s campaign was not without influence on the demand side however as passage of the Aberdeen Act in 1845 allowed the Royal Navy to seize Brazilian slave ships and that put pressure on Brazil and helped spur the 1850 law.

The suppression patrols were expensive (consuming ships, men, and funds), and Britain derived no direct economic benefit from them. Yet, even during the Napoleonic Wars, the Opium Wars, and the Crimean War, the Royal Navy continued to station ships, even high-tech steam ships, off West Africa to catch slavers. Due to the expense, the patrols were controversial and there were attempts to end them. Gwee and Tan look at the votes on ending the patrols and find that ideology was the dominant factor explaining support for the patrols, that is a principled opposition to the slave trade and a belief in the moral cause of abolition kept Britain in the war against slavery even at considerable expense.

Ordinarily, I teach politics without romance and look for interest as an explanation of political action and while I don’t doubt that doing good and doing well were correlated, even during abolition, I also agree with Gwee and Tan that the British war on slavery was primarily driven by ideology and moral principle as both the compensation plan and the support of the anti-slavery patrols attest.

British taxpayers shouldered an enormous military and financial burden to eliminate slavery, reflecting a generosity of spirit and a sincere attempt to address a moral wrong—an act of atonement that stands as one of the most unusual and significant in history.

My Hope Axis podcast with Anna Gát

Here is the YouTube, here is transcript access, here is their episode summary:

The brilliant @tylercowen joins @TheAnnaGat for a lively, wide-ranging conversation exploring hope from the perspective of insiders and outsiders, the obsessed and the competitive, immigrants and hard workers. They talk about talent and luck, what makes America unique, whether the dream of Internet Utopia has ended, and how Gen-Z might rebel. Along the way: Jack Nicholson, John Stuart Mill, road trips through Eastern Europe, the Enlightenment of AI, and why courage shapes the future.

Excerpt:

Tyler Cowen: But the top players I’ve met, like Anand or Magnus Carlsen or Kasparov, they truly hate losing with every bone in their body. They do not approach it philosophically. They can become very miserable as a result. And that’s very far from my attitudes. It shaped my life in a significant way.

Anna Gát: I was so surprised. I was like, what? But actually, what? In Maggie Smith-high RP—what? This never occurred to me that losing can be approached philosophically.

Tyler Cowen: And I think always keeping my equanimity has been good for me, getting these compound returns over long periods of time. But if you’re doing a thing like chess or math or sports that really favors the young, you don’t have all those decades of compound returns. You’ve got to motivate yourself to the maximum extent right now. And then hating losing is super useful. But that’s just—those are not the things I’ve done. The people who hate losing should do things that are youth-weighted, and the people who have equanimity should do things that are maturity and age-weighted with compounding returns.

Excellent discussion, lots of fresh material. Here is the Hope Axis podcast more generally. Here is Anna’s Interintellect project, worthy of media attention. Most of all it is intellectual discourse, but it also seems to be the most successful “dating service” I am aware of.

How to think about AI progress

The Zvi has a good survey post on what is going on with the actual evidence. I have a more general point to make, which I am drawing from my background in Austrian capital theory.

There are easy projects, and there are hard projects. You might also say short-term vs. long-term investments.

The easier, shorter-term projects get done first. For instance, the best LLMs now have near-perfect answers for a wide range of queries. Those answers will not be getting much better, though they may be integrated into different services in higher productivity ways.

Those improvements will yield an ongoing stream of benefits, but you will not see much incremental progress in the underlying models themselves. Ten years from now, the word “strawberry” still will have three r’s, and the LLMs still will tell us that. There are other questions, such as “what is the meaning of life?” where the AI answers also will not get much better. I do not mean that statement as AI pessimism, rather the answers can only get so good because the question is not ideally specified in the first place.

Then there are the very difficult concrete problems, such as in the biosciences or with math olympiad problems, and so on. Progress in these areas seems quite steady and I would call it impressive. But it will take quite a few years before that progress is turned into improvements in daily life. Again, that does not have to be AI pessimism. Just look at how we run our clinical trials, or how long the FDA approval process takes for new drugs, or how many people are reluctant to accept beneficial vaccines. I predict that AI will not speed up those processes nearly as much as it ideally might.

So the AI world before us is rather rapidly being bifurcated into two sectors:

a) progress already is extreme, and is hard to improve upon, and

b) progress is ongoing, but will take a long time to be visible to actual users and consumers

And so people will complain that AI progress is failing us, but mostly they will be wrong. They will be the victim of cognitive error and biases. The reality is that progress is continuing apace, but it swallows up and renders ordinary some of its more visible successes. What is left behind for future progress can be pretty slow.

The politics of depression in young adults

From a recent paper by Catherine Gimbrone, et.al.:

From 2005 to 2018, 19.8% of students identified as liberal and 18.1% identified as conservative, with little change over time. Depressive affect (DA) scores increased for all adolescents after 2010, but increases were most pronounced for female liberal adolescents (b for interaction = 0.17, 95% CI: 0.01, 0.32), and scores were highest overall for female liberal adolescents with low parental education (Mean DA 2010: 2.02, SD 0.81/2018: 2.75, SD 0.92). Findings were consistent across multiple internalizing symptoms outcomes. Trends in adolescent internalizing symptoms diverged by political beliefs, sex, and parental education over time, with female liberal adolescents experiencing the largest increases in depressive symptoms, especially in the context of demographic risk factors including parental education.

Here is the link. This is further evidence for what is by now a well-known proposition.

Wednesday assorted links

1. Flora Yuknovich, painter (NYT).

2. Further comments on Milei and Argentina.

3. My TA Zixuan Ma is starting a blog on China and also recommends these six books.

4. How is New College of Florida doing?

5. Some new Substacks from economics graduate students.

6. Machine learning for economists. And double descent and econometrics.

7. Flood the zone with AI-generated podcasts? “I think that people who are still referring to all AI-generated content as AI slop are probably lazy luddites.” I still think people do not really want this, but I suppose we will see.

8. Roland Fryer on education reform (WSJ).

AI-led job interviews

We study the impact of replacing human recruiters with AI voice agents to conduct job interviews. Partnering with a recruitment firm, we conducted a natural field experiment in which 70,000 applicants were randomly assigned to be interviewed by human recruiters, AI voice agents, or given a choice between the two. In all three conditions, human recruiters evaluated interviews and made hiring decisions based on applicants’ performance in the interview and a standardized test. Contrary to the forecasts of professional recruiters, we find that AI-led interviews increase job offers by 12%, job starts by 18%, and 30-day retention by 17% among all applicants. Applicants accept job offers with a similar likelihood and rate interview, as well as recruiter quality, similarly in a customer experience survey. When offered the choice, 78% of applicants choose the AI recruiter, and we find evidence that applicants with lower test scores are more likely to choose AI. Analyzing interview transcripts reveals that AI-led interviews elicit more hiring-relevant information from applicants compared to human-led interviews. Recruiters score the interview performance of AI-interviewed applicants higher, but place greater weight on standardized tests in their hiring decisions. Overall, we provide evidence that AI can match human recruiters in conducting job interviews while preserving applicants’ satisfaction and firm operations.

That is from a new paper by Brian Jabarian and Luca Henkel.

The evolution of the economics job market

In the halcyon days of 2015-19, openings on the economics job market hovered at around 1900 per year. In 2020, Covid was a major shock, but the market bounced back quickly in 2021 and 2022. Since then, though, the market has clearly been in a funk. 2023, my job market year, saw a sudden dip in postings. 2024 was even worse, with openings falling 16% lower than the 2015-19 average.

At the time, the sudden fall in 2023 seemed mysterious—it was an otherwise healthy year for the broader labor market. In hindsight, it seems like the 2021-22 recovery masked some underlying weakness. The 2020 job market had 500 fewer openings than the 2014-19 average; 2021 and 2022 together produced only around 100 more jobs than the 2014-19 average. In other words, the recovery never made up for the pandemic; by this crude logic, around 400 economist jobs were “destroyed”.

…And of course, all of this decline occurred before the litany of disasters that have recently hit the Econ job market. In May, Jerome Powell announced that the Federal Reserve—perhaps the largest employer of economists in America—would cut its workforce by 10%. The federal government has frozen hiring, as has the World Bank. Hit by the dual threat of fines and looming cuts to federal funding, Harvard, MIT, the University of Washington, Notre Dame, Northwestern University, among others, have announced hiring freezes and budget cuts.

Here is more from Oliver Kim, who also offers a much broader discussion of the meaning of all this.