Results for “Writing” 1387 found

Revisiting the T-Mobile-Sprint Merger

T-Mobile’s takeover of Sprint was controversial among analysts. “If this merger is not anticompetitive,” Eleanor Fox, a trade regulation and antitrust law professor at New York University, told reporters in 2020, “it is hard to know what is.” Yale economist and antitrust scholar Fiona Scott Morton delivered her verdict on the deal in a co-authored 2021 article: “The era of aggressive price competition in wireless is over.” The authors predicted that the wireless industry, whittled down to a big three, would “nestle into a cozy triopoly.”

The prediction proved wrong. Average monthly mobile subscription fees dropped sharply. In the three years before the merger, according to government price data, mobile charges declined in real terms by about 8%. In the three years following the merger, the real price decline has been nearly 12%.

These trends were even more impressive given dramatically improving network performance. Before the merger, the top four U.S. carriers delivered data download speeds averaging about 26 megabits per second, nearly all via 3G or 4G. By early 2023, with 5G deployments spreading, Verizon and AT&T data flowed 24% to 39% faster, while T-Mobile was more than three times as fast as before. T-Mobile’s high-speed coverage had also expanded; half of its connections were via 5G by January 2023, against just 10% to 20% for its rivals.

…Further evidence that the merger of T-Mobile and Sprint was pro-competitive was seen with Verizon and AT&T share prices. From 2018 to 2023, Verizon and AT&T stock prices declined sharply, losing more than a third of their real value. The postmerger marketplace was a great victory for T-Mobile but a blow for its rivals. The cozy-cartel thesis collapsed.

That’s the excellent Tom Hazlett writing in the WSJ–useful facts to remember when thinking about the current rise of antitrust.

What should I ask Michael Nielsen?

I will be doing a Conversation with him. No description of Michael quite does him justice, but here is Wikipedia:

Michael Aaron Nielsen (born January 4, 1974) is a quantum physicist, science writer, and computer programming researcher living in San Francisco.

In 1998, Nielsen received his PhD in physics from the University of New Mexico. In 2004, he was recognized as Australia’s “youngest academic” and was awarded a Federation Fellowship at the University of Queensland. During this fellowship, he worked at the Los Alamos National Laboratory, Caltech, and at the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics.

Alongside Isaac Chuang, Nielsen co-authored a popular textbook on quantum computing, which has been cited more than 52,000 times as of July 2023.

In 2007, Nielsen shifted his focus from quantum information and computation to “the development of new tools for scientific collaboration and publication”, including the Polymath project with Timothy Gowers, which aims to facilitate “massively collaborative mathematics.” Besides writing books and essays, he has also given talks about open science. He was a member of the Working Group on Open Data in Science at the Open Knowledge Foundation.

Nielsen is a strong advocate for open science and has written extensively on the subject, including in his book Reinventing Discovery, which was favorably reviewed in Nature and named one of the Financial Times’ best books of 2011.

In 2015 Nielsen published the online textbook Neural Networks and Deep Learning, and joined the Recurse Center as a Research Fellow. He has also been a Research Fellow at Y Combinator Research since 2017.

In 2019, Nielsen collaborated with Andy Matuschak to develop Quantum Computing for the Very Curious, a series of interactive essays explaining quantum computing and quantum mechanics. With Patrick Collison, he researched whether scientific progress is slowing down.

Here is Michael’s Notebook, well worth a browse and also a deeper read. Here is Michael on Twitter. So what should I ask him? (I’m going to ask him about Olaf Stapledon in any case, so no need to mention that.)

Sunday assorted links

1. The pessimistic view on Ethiopia.

2. Inside the NBA’s chess club.

3. Brian Goff on education and the cost disease.

4. Genes and depression and bad luck is endogenous.

5. TC on internet writing. And TC on Bill Laimbeer on passive-aggressive economists.

6. How should state and local governments respond to illegal retail cannabis?

7. Diaper spa for adults, and a licensing issue too.

8. The Karpathy review of Apple Vision Pro. I likely will try it once there is a small army of people who have figured out the ins and outs and who can serve as tutors, including for setting the thing up. One reason I am not “first in line” with this device is that it strikes me as a “technology of greater vividness” (a bit like some drugs? or downhill skiing?), and not so much a “technology to understand people and cultures more deeply.” I think the latter interests me more, and I also do better with the latter. But perhaps I am wrong! To be clear, I am not arguing that “technologies of greater vividness” are objectively or intrinsically worse, if anything more people seem to prefer them.

My new podcast with Dwarkesh Patel

We discussed how the insights of Hayek, Keynes, Smith, and other great economists help us make sense of AI, growth, risk, human nature, anarchy, central planning, and much more.

Dwarkesh is one of the very best interviewers around, here are the links. If Twitter is blocked to you, here is the transcript, here is Spotify, among others. Here is the most salacious part of the exchange, highly atypical of course:

Dwarkesh Patel 00:17:16

If Keynes were alive today, what are the odds that he’s in a polycule in Berkeley, writing the best written LessWrong post you’ve ever seen?

Tyler Cowen 00:17:24

I’m not sure what the counterfactual means. Keynes is so British. Maybe he’s an effective altruist at Cambridge. Given how he seemed to have run his sex life, I don’t think he needed a polycule. A polycule is almost a Williamsonian device to economize on transaction costs. But Keynes, according to his own notes, seems to have done things on a very casual basis.

And on another topic:

Dwarkesh Patel 00:36:44

We’re talking, I guess, about like GPT five level models. When you think in your mind about like, okay, this is GPT five. What happens with GPT six, GPT seven. Do you see it? Do you still think in the frame of having a bunch of RAs, or does it seem like a different sort of thing at some point?

Tyler Cowen 00:36:59

I’m not sure what those numbers going up mean, what a GPT seven would look like, or how much smarter it could get. I think people make too many assumptions there. It could be the real advantages are integrating it into workflows by things that are not better GPTs at all. And once you get to GPT, say, 5.5, I’m not sure you can just turn up the dial on smarts and have it, like, integrate general relativity and quantum mechanics.

Dwarkesh Patel 00:37:26

Why not?

Tyler Cowen 00:37:27

I don’t think that’s how intelligence works. And this is a Hayekian point. And some of these problems, there just may be no answer. Like, maybe the universe isn’t that legible, and if it’s not that legible, the GPT eleven doesn’t really make sense as a creature or whatever.

Dwarkesh Patel 00:37:44

Isn’t there a Hayekian argument to be made that, listen, you can have billions of copies of these things? Imagine the sort of decentralized order that could result, the amount of decentralized tacit knowledge that billions of copies talking to each other could have. That in and of itself, is an argument to be made about the whole thing as an emergent order will be much more powerful than we were anticipating.

Tyler Cowen 00:38:04

Well, I think it will be highly productive. What “tacit knowledge” means with AIs, I don’t think we understand yet. Is it by definition all non-tacit? Or does the fact that how GPT-4 works is not legible to us or even its creators so much? Does that mean it’s possessing of tacit knowledge, or is it not knowledge? None of those categories are well thought out, in my opinion. So we need to restructure our whole discourse about tacit knowledge in some new, different way. But I agree, these networks of AIs, even before, like, GPT-11, they’re going to be super productive, but they’re still going to face bottlenecks, right? And I don’t know how good they’ll be at, say, overcoming the behavioral bottlenecks of actual human beings, the bottlenecks of the law and regulation. And we’re going to have more regulation as we have more AIs.

You will note I corrected the AI transcriber on some minor matters. In any case, self-recommending, and here is the YouTube embed:

What should I ask Benjamin Moser?

Yes I will be doing a Conversation with him. Here is one outdated bit from his home page:

Benjamin Moser was born in Houston. He is the author of Why This World: A Biography of Clarice Lispector, a finalist for the National Book Critics’ Circle Award and a New York Times Notable Book of 2009. For his work bringing Clarice Lispector to international prominence, he received Brazil’s first State Prize for Cultural Diplomacy. He won a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2017, and his latest book, Sontag: Her Life and Work, won the Pulitzer Prize.

I am a big fan of his new book on the Dutch painters, The Upside-Down World: Meetings with Dutch Masters. He lives in Utrecht and is also an expert on Brazil. Here is his Wikipedia page. Here are other assorted writings by him.

So what should I ask him?

What should I ask Marilynne Robinson?

Yes I will be doing a Conversation with her. Here is from Wikipedia:

Marilynne Summers Robinson (born November 26, 1943) is an American novelist and essayist. Across her writing career, Robinson has received numerous awards, including the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 2005, National Humanities Medal in 2012, and the 2016 Library of Congress Prize for American Fiction. In 2016, Robinson was named in Time magazine’s list of 100 most influential people. Robinson began teaching at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop in 1991 and retired in the spring of 2016.

Robinson is best known for her novels Housekeeping (1980) and Gilead (2004). Her novels are noted for their thematic depiction of faith and rural life. The subjects of her essays span numerous topics, including the relationship between religion and science, US history, nuclear pollution, John Calvin, and contemporary American politics.

Her next book is Reading Genesis, on the Book of Genesis. So what should I ask her?

My Conversation with Rebecca F. Kuang

Here is the audio, video, and transcript, here is the episode summary:

Rebecca F. Kuang just might change the way you think about fantasy and science fiction. Known for her best-selling books Babel and The Poppy War trilogy, Kuang combines a unique blend of historical richness and imaginative storytelling. At just 27, she’s already published five novels, and her compulsion to write has not abated even as she’s pursued advanced degrees at Oxford, Cambridge, and now Yale. Her latest book, Yellowface, was one of Tyler’s favorites in 2023.

She sat down with Tyler to discuss Chinese science-fiction, which work of fantasy she hopes will still be read in fifty years, which novels use footnotes well, how she’d change book publishing, what she enjoys about book tours, what to make of which Chinese fiction is read in the West, the differences between the three volumes of The Three Body Problem, what surprised her on her recent Taiwan trip, why novels are rarely co-authored, how debate influences her writing, how she’ll balance writing fiction with her academic pursuits, where she’ll travel next, and more.

Here is one excerpt:

COWEN: Why do you think that British imperialism worked so much better in Singapore and Hong Kong than most of the rest of the world?

KUANG: What do you mean by work so much better?

COWEN: Singapore today, per capita — it’s a richer nation than the United States. It’s hard to think, “I’d rather go back and redo that whole history.” If you’re a Singaporean today, I think most of them would say, “We’ll take what we got. It was far from perfect along the way, but it worked out very well for us.” People in Sierra Leone would not say the same thing, right?

Hong Kong did much better under Britain than it had done under China. Now that it’s back in the hands of China, it seems to be doing worse again, so it seems Hong Kong was better off under imperialism.

KUANG: It’s true that there is a lot of contemporary nostalgia for the colonial era, and that would take hours and hours to unpack. I guess I would say two things. The first is that I am very hesitant to make arguments about a historical counterfactual such as, “Oh, if it were not for the British Empire, would Singapore have the economy it does today?” Or “would Hong Kong have the culture it does today?” Because we don’t really know.

Also, I think these broad comparisons of colonial history are very hard to do, as well, because the methods of extraction and the pervasiveness and techniques of colonial rule were also different from place to place. It feels like a useless comparison to say, “Oh, why has Hong Kong prospered under British rule while India hasn’t?” Et cetera.

COWEN: It seems, if anywhere we know, it’s Hong Kong. You can look at Guangzhou — it’s a fairly close comparator. Until very recently, Hong Kong was much, much richer than Guangzhou. Without the British, it would be reasonable to assume living standards in Hong Kong would’ve been about those of the rest of Southern China, right? It would be weird to think it would be some extreme outlier. None others of those happened in the rest of China. Isn’t that close to a natural experiment? Not a controlled experiment, but a pretty clear comparison?

KUANG: Maybe. Again, I’m not a historian, so I don’t have a lot to say about this. I just think it’s pretty tricky to argue that places prospered solely due to British presence when, without the British, there are lots of alternate ways things could have gone, and we just don’t know.

Interesting throughout.

Friday assorted links

1. Are some Latin American countries “quiet quitting” the war on drugs?

3. Some much-needed perspective on the “Chinese brain killer virus.”

4. Detroit Beer Exchange closes, erstwhile floating price markets in everything.

5. On Solano and cars, noting that I don’t find the car outcomes so bad myself.

6. How good is the three-minute intelligence test?

8. BAP on populism and libertarianism.

There is now an Andrew Gelman newsletter.

Get Out of Jail Cards, 2

“Courtesy cards,” are cards given out by the NYC police union (and presumably elsewhere) to friends and family who use them to get easy treatment if they are pulled over by a cop. I was stunned when I first wrote about these cards in 2018. I thought this was common only in tinpot dictatorships and flailing states. The cards even come in levels, gold, silver and bronze!

A retired police officer on Quora explains how the privilege is enforced:

The officer who is presented with one of these cards will normally tell the violator to be more careful, give the card back, and send them on their way.

…The other option is potentially more perilous. The enforcement officer can issue the ticket or make the arrest in spite of the courtesy card. This is called “writing over the card.” There is a chance that the officer who issued the card will understand why the enforcement officer did what he did, and nothing will come of it. However, it is equally possible that the enforcement officer’s zeal will not be appreciated, and the enforcement officer will come to work one day to find his locker has been moved to the parking lot and filled with dog excrement.

A NYTimes article discusses the case of Mathew Bianchi, a traffic cop who got sick of letting dangerous speeders go when they presented their cards.

By the time he pulled over the Mazda in November 2018, drivers were handing Bianchi these cards six or seven times a day. (!!!, AT)

…[He gives the ticket]…The month after he stopped the Mazda, a high-ranking police union official, Albert Acierno, got in touch. He told Bianchi that the cards were inviolable. He then delivered what Bianchi came to think of as the “brother speech,” saying that cops are brothers and must help each other out. That the cards were symbols of the bonds between the police and their extended family and friends.

Bianchi was starting to view the cards as a different kind of symbol: of the impunity that came with knowing someone on the force, as if New York’s rules didn’t apply to those with connections. Over the next four years, he learned about the unwritten rules that have come to hold sway in the Police Department.

Bianchi is reassigned, given shit jobs, isn’t promoted etc. Mayor Adams and police chief Chief Maddrey protect this utterly corrupt system.

A congestion theory of unemployment fluctuations

Yusuf Mercan, Benjamin Schoefer, and Petr Sedláček, newly published in American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics. I best liked this excerpt from p.2, noting that “DMP” refers to the Nobel-winning Diamond-Mortensen-Pissarides search model of unemployment:

This congestion mechanism improves the business cycle performance of the DMP model considerably. It raises the volatility of labor market tightness tenfold, to empirically realistic levels. It produces a realistic Beveridge curve despite countercyclical separations. On its own, it accounts for around 30–40 percent of US unemployment fluctuations and much of its persistence. In addition, the model accounts for a range of other business cycle patterns linked to unemployment: the excess procyclicality of wages of newly hired workers compared to average wages, the countercyclical labor wedge, large countercyclical earnings losses from displacement and from labor market entry, and the long-run insensitivity of unemployment to policies such as unemployment insurance.

And by their congestion mechanism the authors mean this:

…a constant returns to scale aggregate production function that exhibits diminishing returns to new hires, a feature we call congestion in hiring.

I find that assumption plausible. It remains the case that the DMP model is grossly underrepresented in on-line writings on economics, on Twitter, and in the blogosphere. It won three Nobel Prizes, yet it also suggests that the “simple” manipulation of spending or nominal values does not automatically restore higher levels of employment.

Here are less gated versions of the paper.

Prompts for economists

This page contains example prompts and responses intended to showcase how generative AI, namely LLMs like GPT-4, can benefit economists.

Example prompts are shown from six domains: ideation and feedback; writing; background research; coding; data analysis; and mathematical derivations.

The framework as well as some of the prompts and related notes come from Korinek, A. 2023. “Generative AI for Economic Research: Use Cases and Implications for Economists“, Journal of Economic Literature, 61 (4): 1281–1317.

Each application area includes 1-3 prompts and responses from an LLM, often from the field of development economics, along with brief notes. The prompts will be updated periodically.

Here is the page from Jesse Lastunen.

Thursday assorted links

1. Claims about the Russian defense sector.

2. South Korea to ban dog meat.

3. Microsoft debates what to do with AI lab in China, perhaps EAers should discuss this more? (NYT) EA is right about many issues, but for far too long foreign policy has been a weak suit of the philosophy. And here is U.S. companies talking to China about AI safety (FT).

4. Johor Bahru metro concept map. And “Malaysia and Singapore agreed to jointly develop a special economic zone and explore a range of measures including passport-free travel to boost trade between the neighbors that each count the other as the No. 2 trading partner.” (Bloomberg, this has been a longstanding prediction of mine).

Sunday assorted links

Kamil Kovar on the German debt brake (from my email)

I was wondering if you would consider writing a post about the German debt brake in light of recent developments? Personally, I am not a huge fan of discussions about fiscal policy (or even worse, austerity…), as I feel they are mostly Rorschach test without much deep thinking. But I did find the recent developments intriguing because they challenge my priors so I am wondering what whether your thinking has changed as well.

My prior was that some form of constitutional debt break is a reasonable mechanism to deal with the pro-debt bias resulting from democratic political process. Of course, some of the recent German experience has challenged that. For example, debt break legislation lead to a lot of “bad” legislating, which was exposed by the court recently. Similarly, the debt break is leading Germany to cut spending and increase taxes relative to what the government would want; given the weakness in German economy this does not seem like optimal fiscal policy (but might be – monetary policy by choice restrictive, and many have called on fiscal to be too). And more broadly, there is a fair argument to be made that it has constrained government investment during last decade, which was an optimal time to do government investment given the negative interest rates.

Part of this I think is a question of imperfect design/implementation. The deficit threshold of -0.35% is higher than I would imagine. Absence of any relationship to current interest rates or effect on future debt levels ala CBO analysis is probably not what finance theory would suggest. And the cyclical adjustment seems suspicious: my understanding is that currently the cyclical adjustment allows for 0.1% of GDP of extra deficit, corresponding to 1% output gap and 1/10 elasticity, see here.[1] But I suspect imperfect design/implementation will always be a feature of these kind of legalistic rules, so should not be waved away.

At the same time, I find lot of the commentary rather subpar. I have in mind for example arguments in this article. While I can see that investment would likely be higher last decade in absence of debt break, saying that debt break results in “Germany that doesn’t invest and massively falls behind in economic terms” is just shocking, as it implies that investment can be only done through higher deficits. Moreover, arguing that debt break has to be abolished so that Germany can invest to deal with geopolitics and green transition is simply ignoring that Germany already found a legally-sound solution to such kind of problems when it constitutionally created its 100 billion euro defense spending fund. Together with the wise use of debt break suspensions during last 4 years this shows that there is sufficient flexibility built into this, despite what the commentators would suggest (“but in practice it’s too inflexible”), as long as there is consensus on such actions. But maybe this points towards the actual problem: maybe in current society building political consensus has become too hard, so that mechanisms which rely too much on such consensus are doomed to create more problems than their benefit. The US debt ceiling comes to mind. Similarly, I think CDU secretly agrees with some of the governments desires, but will not act on them either because it wishes for the government to collapse or is afraid of voters’ reaction.

Very curious what is your thinking and how it has changed.

Kamil

P.S.: Relatedly, I often see left-of-center economists citing IMF research that austerity does not yield decrease in government debts relative to GDP. While I understand the value of such research, I am not sure what are the people suggesting. If austerity cannot lower debt to GDP, what can? I don’t think that most economists would suggest that large scale government investment is going to lower debt to GDP. So it the conclusion that we can never lower debt to GDP?

Kamil expands on these points in a blog post, concluding:

So maybe this is the main critique of the constitutional debt break: In the older world it might have been an good tool, but given the general unravelling of political process around the world, it adds too much of a constraint leading to worse outcomes. It simply is not fit for the current times. It might not be. As for me, I am currently in state of “not sure”.

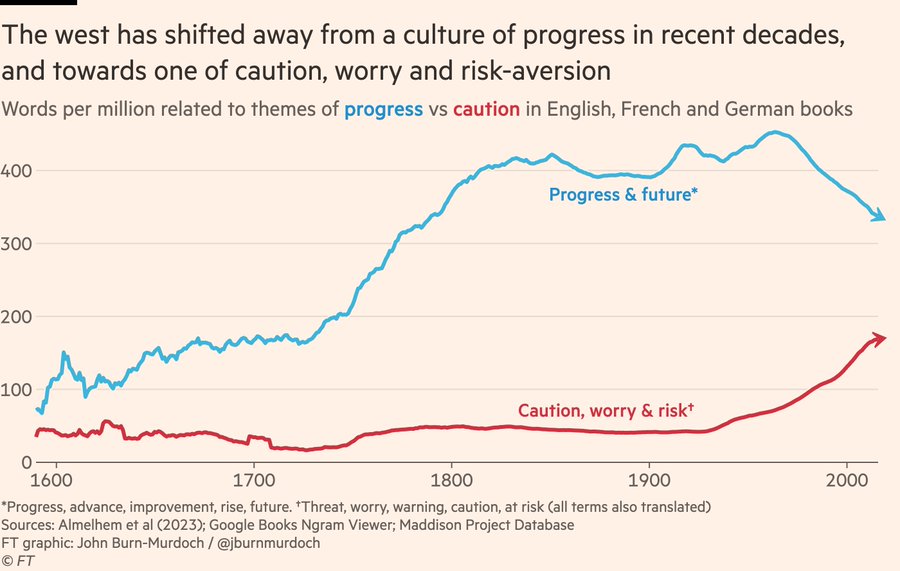

We need more talk of progress

Here is the underlying John-Burn Murdoch FT piece, pointer here. And a text excerpt:

Ruxandra Teslo, one of a growing community of progress-focused writers at the nexus of science, economics and policy, argues that the growing scepticism around technology and the rise in zero-sum thinking in modern society is one of the defining ideological challenges of our time.

I am pleased that Ruxandra is now also an Emergent Ventures winner.