The Most Expensive Mile of Subway Track on Earth

Blogger Alon Levy first drew attention to the fact that building a subway costs far more in New York City than elsewhere in the United States or the world. In a superb investigation the NYTimes updates that finding and investigates why:

The estimated cost of the Long Island Rail Road project, known as “East Side Access,” has ballooned to $12 billion, or nearly $3.5 billion for each new mile of track — seven times the average elsewhere in the world. The recently completed Second Avenue subway on Manhattan’s Upper East Side and the 2015 extension of the No. 7 line to Hudson Yards also cost far above average, at $2.5 billion and $1.5 billion per mile, respectively.

So why are costs so high? The NYTimes concludes:

For years, The Times found, public officials have stood by as a small group of politically connected labor unions, construction companies and consulting firms have amassed large profits.

Trade unions, which have closely aligned themselves with Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo and other politicians, have secured deals requiring underground construction work to be staffed by as many as four times more laborers than elsewhere in the world, documents show.

Construction companies, which have given millions of dollars in campaign donations in recent years, have increased their projected costs by up to 50 percent when bidding for work from the M.T.A., contractors say.

Consulting firms, which have hired away scores of M.T.A. employees, have persuaded the authority to spend an unusual amount on design and management, statistics indicate.

Where the Times piece goes well beyond what has been discussed before is the detail by which it supports these conclusions and the careful comparison with similar but much cheaper projects elsewhere in the world such as Paris.

It will not escape notice that New York buys subway construction the way all of America buys health care.

Read the whole thing.

Why has investment been weak?

Germán Gutiérrez and Thomas Philippon have a new paper on this topic:

We analyze private fixed investment in the U.S. over the past 30 years. We show that investment is weak relative to measures of profitability and valuation — particularly Tobin’s Q, and that this weakness starts in the early 2000’s. There are two broad categories of explanations: theories that predict low investment along with low Q, and theories that predict low investment despite high Q. We argue that the data does not support the first category, and we focus on the second one. We use industry-level and firm-level data to test whether under-investment relative to Q is driven by (i) financial frictions, (ii) changes in the nature and/or localization of investment (due to the rise of intangibles, globalization, etc), (iii) decreased competition (due to technology, regulation or common ownership), or (iv) tightened governance and/or increased short-termism. We do not find support for theories based on risk premia, financial constraints, safe asset scarcity, or regulation. We find some support for globalization; and strong support for the intangibles, competition and short-termism/governance hypotheses. We estimate that the rise of intangibles explains 25-35% of the drop in investment; while Concentration and Governance explain the rest. Industries with more concentration and more common ownership invest less, even after controlling for current market conditions and intangibles. Within each industryyear, the investment gap is driven by firms owned by quasi-indexers and located in industries with more concentration and more common ownership. These firms return a disproportionate amount of free cash flows to shareholders. Lastly, we show that standard growth-accounting decompositions may not be able to identify the rise in markups.

On the road I have yet to read it, but it looks like one of the most important papers of the year.

My Law and Literature reading list 2018

The New English Bible, Oxford Study Edition [not all of it]

Guantanamo Diary, by Mohamedou Ould Slahi

Petina Gappah, The Book of Memory

Glaspell’s Trifles, available on-line.

Year’s Best SF 9, edited by David G. Hartwell and Kathryn Cramer, used or Kindle edition is recommended

The Metamorphosis, In the Penal Colony, and Other Stories, by Franz Kafka, edited and translated by Joachim Neugroschel.

In the Belly of the Beast, by Jack Henry Abbott.

Sherlock Holmes, The Complete Novels and Stories, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, volume 1, also on-line.

I, Robot, by Isaac Asimov.

Juan Gabriel Vasquez, Reputations

The Pledge, Friedrich Durrenmatt.

Ian McEwan, The Children Act

Shakespeare, The Tempest, Folger edition

Margaret Atwood, Hag-Seed

Curtis Dawkins, The Graybar Hotel

Movies: To be determined.

Assorted Thursday links

1. Why did Bitcoin take so long? And is it ugly?

2. Cashless restaurants in NYC (NYT).

3. “...infants who look like their father at birth are healthier one year later. The reason is such father–child resemblance induces a father to spend more time engaged in positive parenting.” If looks could kill…

4. Are wealthier millionaires happier?

6. Does faculty tweeting help the reputation of universities?

In Understanding Business Fluctuations Not all GDP is Equal

In standard macroeconomic models, GDP is GDP and an industry is important only to the extent that it produces GDP. In other words, there are big industries and small industries but there are no special industries. The standard view implies that the structure of production can be ignored. It doesn’t matter, for example, whether an industry sells to final consumers or to other businesses. It doesn’t matter whether an industry sells an easy-to-substitute product or a hard-to-substitute product. And it doesn’t matter whether an industry is a weak-tie link or a strong-tie link. Thus, in the standard view, the oil industry is no more important for understanding economic fluctuations than say the retail sales industry, since they are about the same size.

The standard view isn’t arbitrary, Hulten proved that it was true under certain assumptions. Hulten’s theorem appeared to offer a very useful simplification and so it diverted the attention of economists away from trying to model the structure of production.

But I’ve always been skeptical. One reason is that rapid increases in the price of oil have preceded almost all U.S. recessions (see Hamilton’s papers) and such increases appear to be much more important than the size of the oil sector would allow. More generally, although the canonical real business cycle model emphasizes aggregate technology shocks, I’ve always looked favorably on variations with sectoral shocks–this is one reason why Modern Principles is one of the few principles of economics textbooks to devote significant attention to real shocks, including oil shocks, and the mechanisms that can transmit and amplify these shocks from one sector to the wider economy.

The sectoral approach gets new support in a recent paper, The Macroeconomic Impact of Microeconomic Shocks: Beyond Hulten’s Theorem (non-gated) by Baqaee and Farhi. The authors show that Hulten’s theorem offers a true simplification only under very restrictive conditions. Relax those conditions and what seem like second-order mechanisms can have first-order effects. The structure of production–how industries are linked to one another, elasticities of substitution, reallocation speeds and so forth–matters in theory.

In a calibration Baqaee and Farhi consider “the response of GDP to shocks to specific industries” and:

…It turns out that for a large negative shock, the “oil and gas” industry produces the largest negative response in GDP – this despite the fact that the oil and gas industry is not the largest industry in the economy.

Why do so many intellectuals favor governmental solutions?

Building on an essay by Robert Nozick, here is Julian Sanchez:

If the best solutions to social problems are generally governmental or political, then in a democratic society, doing the work of a wordsmith intellectual is a way of making an essential contribution to addressing those problems. If the best solutions are generally private, then this is true to a far lesser extent: The most important ways of doing one’s civic duty, in this case, are more likely to encompass more direct forms of participation, like donating money, volunteering, working on technological or medical innovations that improve quality of life, and various kinds of socially conscious entrepreneurial activity.

You might, therefore, expect a natural selection effect: Those who feel strongly morally motivated to contribute to the amelioration of social ills will naturally gravitate toward careers that reflect their view about how this is best achieved. The choice of a career as a wordsmith intellectual may, in itself, be the result of a prior belief that social problems are best addressed via mechanisms that are most dependent on public advocacy, argument and persuasion—which is to say, political mechanisms.

…If the world is primarily made better through private action, then the most morally praiseworthy course available to a highly intelligent person of moderate material tastes might be to pursue a far less inherently interesting career in business or finance, live a middle-class lifestyle, and devote one’s wealth to various good causes. In this scenario, after all, the intellectual who could make millions for charity as a financier or high-powered attorney, but prefers to take his compensation in the form of leisure time and interesting work, is not obviously morally better than the actual financier or attorney who uses his monetary compensation to purchase material pleasures.

Here is the full essay, via Jeffrey Flier.

Further points on how to understand modern India (from the comments)

Good post.

There are a few other topics that can serve as useful handles to “understand” India.

1. Study the folk history of the popular Indian pilgrimage sites –

For a lot of people, Hinduism is associated with abstruse metaphysics, mysticism, Vedanta, and Yoga. And this obsession with the high falutin theoretical stuff, means that many students of Hinduism don’t pay as much attention to the pop-religion on the ground. And this religion is best understood by actually understanding the few hundred important pilgrimage sites scattered across the country. Each of these sites is ancient and has a “legend” associated with it. (the so-called Sthala Purana). The civilizational unity of India is largely accomplished because of the pan Indian reverence for these pilgrimage sites. Be it Benaras in the North, Kolhapur in the west, Srirangam in the south, or Puri in the East. A nice way to get started on this is Diana Eck’s book – “India – A Sacred Geography” where she makes a strong case for the theory that the idea of one India is one that is primarily stemming out of the pilgrimage experience of Hindus.

This study of pop religion will be messy and frustrating for people from an Abrahamic monotheistic background. But there is no better way to understand what makes Indians tick spiritually, and why every Indian is a millionaire when it comes to Religion.

2. Study of the history of Indian mathematics –

This may seem like an odd handle to understand India. But in my view it is useful, because Indian mathematical tradition that goes back to roughly 700 BCE, is one that is highly empirical, algebraic, and averse to theorizing and rigorous proofs. So it tells you a lot about the Indian mind. Which is very different from the Greek mind, in that it places a very very low premium on “neatness”, and a high premium on “improvisation”.

Unlike the Greeks, Indian mathematics is not that big on geometry. And also not that big on “visualization”. While someone like Euclid leveraged diagrams to make his point, Indian mathematicians like Brahmagupta and Bhaskara I/II, just stated results in 2-line or 4-line verses.

The Indian mathematical tradition is arguably the greatest Indian contribution to human civilization. Particularly the decimal number system, infinite series, and the algebraic orientation in general (markedly different from the Greek emphasis on geometry). The tradition includes Sulba Sutras (700BCE), Aryabhata (400CE), Varahamihira (400CE), Brahmagupta (500-600CE), Bhaskara I (600CE), Bhaskara II (1100-1200 CE), and ofcourse the famed Kerala school of mathematics (14th century). Madhava from the Kerala school approximated Pi to 13 decimal places. In more recent times, the most distinguished mathematical mind is ofcourse Srinivasa Ramanujan, very much a man in the Indian tradition, who disdained proofs and conventional rigor, and instead relied on intuition and heuristics.

3. Study of Indian poetry and music and its emphasis on meter

This is something that is again uniquely Indian – the very very high emphasis on meter. Which is a consequence of the Indian oral tradition and cultural aversion to writing. Which continues to this day. The emphasis on meter and rhyming was partly an aid to memorization and rote learning. And this emphasis begins with the Vedas (the earliest religious literature, preserved orally for some 1500 years before they were written down in the common era) And you see this in Indian poetry and even Indian film music to this day! Bollywood songs are characterized by their metrical style and perfect rhyming, which you don’t always see in western popular music. In that sense, the metrical legacy of the Vedas is still alive in popular culture.

That is from Shrikanthk.

Amateur meteorology in India

India’s amateur forecasters are not formally trained in meteorology. Still, many people rely on individual blogs or Facebook pages that have built reputations after years of forecasting. “U r a gr8 help” reads a message Srikanth received from one reader of his Chennai Rains blog, which he manages with two other people. Another reader invited the Chennai Rains team to his wedding.

Weather wonks such as Srikanth are scattered around India. In the financial hub of Mumbai, 64-year-old retired businessman Rajesh Kapadia has become a local hero for the predictions on his blog, Vagaries of the Weather. Kapadia’s passion for meteorology started when his father gave him a wall-mounted thermometer as a teenager. At first, people mocked his weather obsession. “They thought I was a madman looking at clouds,” he said.

In the northern Indian city of Rohtak, 16-year-old Navdeep Dahiya sends local farmers WhatsApp and Facebook weather alerts while studying for school exams. Dahiya describes 2014 as his “golden year” — it was the year he went on a school trip to the India Meteorological Department. “I saw how farmers are helped by the weather,” he said. “I saw how they use all these gadgets to predict weather.”

Dahiya soon set up his own weather station at home; he has thermometers, an automatic rain gauge and a digital screen. Now known as Rohtak Weatherman, Dahiya sends out weather reports in Hindi and gets phone calls from farmers in the region asking for predictions.

That is from Vidhi Doshi at WaPo. I would be very interested in knowing how the forecasts of the amateurs (probably not the right word at this point) compare to the professionals.

Wednesday assorted links

How to think about 2018 — predictions for the year to come

That is the topic of my latest Bloomberg column, here is one bit:

The onset of a new year brings plenty of predictions, and so I will hazard one: Many of the biggest events of 2018 will be bound together by a common theme, namely the collision of the virtual internet with the real “flesh and blood” world. This integration is likely to steer our daily lives, our economy, and maybe even politics to an unprecedented degree.

For instance, the coming year will see a major expansion of the “internet of things”…

And:

But whatever your prediction for the future, this integration of real and virtual worlds will either make or break bitcoin and other crypto-assets.

And:

So far the process-oriented and Twitter-oriented foreign policies have coexisted, however uneasily. I see 2018 as the year where these two foreign policies converge in some manner. Either Trump’s tweets end up driving actual foreign policy and its concrete, “boots on the ground” realization, or the real-world policy prevails and the tweets become far less relevant.

There is much more at the link, including a discussion of cyberwar, China and facial surveillance technologies, and the French attempt to ban smartphones at schools.

Critique of the blockchain contra blockchain

Here is an excellent Kai Stinchcombe essay, piling together many of the extant criticisms of blockchains, here is one excerpt:

There are four additional problems with a blockchain-driven approach. First, you’re relying on single-point encryption — your own private keys — rather than a more sophisticated system that might involve two-factor authorization, intrusion detection, volume limits, firewalls, remote IP tracking, and the ability to disconnect the system in an emergency. Second, price tradeoffs are entirely implausible — the bitcoin blockchain has consumed almost a billion dollars worth of electricity to hash an amount of data equivalent to about a sixth of what I get for my ten dollar a month dropbox subscription. Fourth, systematically choosing where and how much to replicate data is an advantage in the long run — the blockchain’s defaults on data replication just aren’t that smart. And finally, Dropbox and Box.com and Google and Microsoft and Apple and Amazon and everyone else provide a set of valuable other features that you don’t actually want to go develop on your own. Analogous to Visa, the problem isn’t storing data, it’s managing permissions, un-sharing what you shared before, getting an easy-to-view document history, syncing it on multiple devices, and so on.

Overstated, in my view, but worth a ponder nonetheless. How many years does blockchain get before we start being unimpressed? Ten? Thirty?

Tuesday assorted links

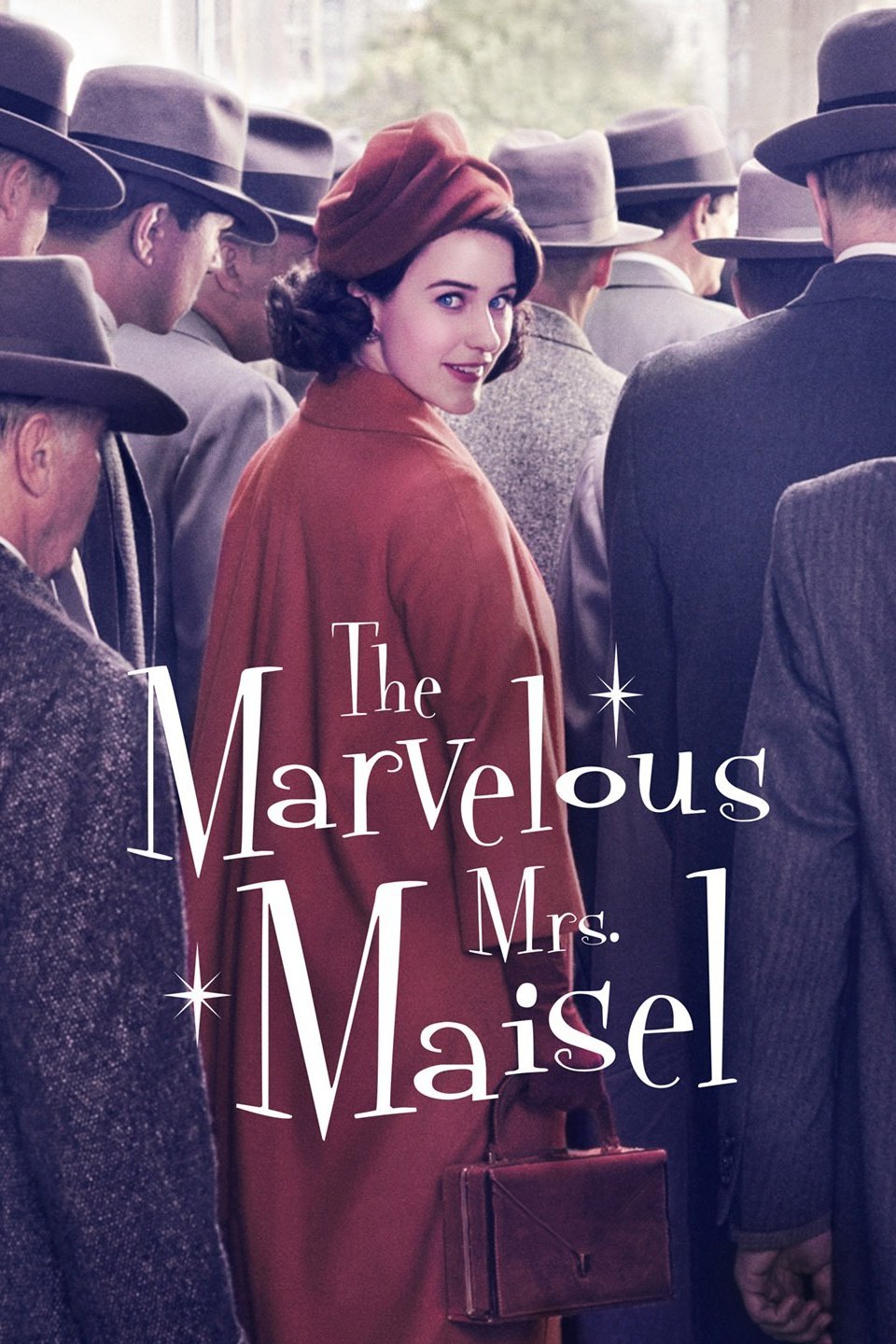

Binge-Worthy and Not Binge-Worthy

Top of my list for binge-worthy over the holiday season is The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel on Amazon Prime. It’s written and directed by Amy Sherman-Palladino and like her previous show, The Gilmore Girls, it features whip-smart women spouting fast-paced dialogue but here decidedly more ribald and foul-mouthed. The show, set in 1958 New York, features Rachel Brosnahan as the eponymous Midge Maisel who,  when her husband leaves her for a shiksa, finds unexpected release by explosively ripping into the situation in a public monologue that gets her arrested for indecency alongside comedian Lenny Bruce. Midge is at the center of three New York City Jewish cultures, the intellectual, represented by her father the mathematician Abe Weissman (in an excellent performance by Tony Shalhoub), the Yiddish business culture as represented by her father-in-law, Moishe Maisel played by Kevin Pollak, and the cultural critic represented by Lenny Bruce (played by Luke Kirby). I especially liked the show as a portrait of the young artist, drawing on and combining all three cultures, honing her material, working it out, mastering the process. Brosnahan as Midge is the very definition of winning. Alex Borstein as aspiring agent Susie Myerson gets some of the best lines. The children are mute and faceless, an interesting choice.

when her husband leaves her for a shiksa, finds unexpected release by explosively ripping into the situation in a public monologue that gets her arrested for indecency alongside comedian Lenny Bruce. Midge is at the center of three New York City Jewish cultures, the intellectual, represented by her father the mathematician Abe Weissman (in an excellent performance by Tony Shalhoub), the Yiddish business culture as represented by her father-in-law, Moishe Maisel played by Kevin Pollak, and the cultural critic represented by Lenny Bruce (played by Luke Kirby). I especially liked the show as a portrait of the young artist, drawing on and combining all three cultures, honing her material, working it out, mastering the process. Brosnahan as Midge is the very definition of winning. Alex Borstein as aspiring agent Susie Myerson gets some of the best lines. The children are mute and faceless, an interesting choice.

Bright, the $90 million “epic” on Netflix is watchable but ho-hum. The premise seems straight out of Hollywood mad libs: orcs+elves+buddy cop movie in modern LA. Let’s get Will Smith! The undertones of “orcs are like gang-banger blacks” was off-putting.

Godless on Netflix was a near miss. It’s a Western and has a great performance by Jeff Daniels as a spiritual, psychopath gang leader. In fact, I liked everyone in it including Michelle Dockery and Scoot McNairy (Gordon Clark from Halt and Catch Fire) but the show has no center. Is it about Dockery’s character, the single mom with an Indian son, trying to make it on the farm? Is it about the town of women who all instantly lost their husbands in a terrifying mining accident? It is about the going-blind Sheriff trying to track  down the killer-gang in one last attempt to win the woman he loves? Or is it about the buffalo cowboys trying to make their way in a white man’s land after the civil war? Any of these stories could have been, indeed would have been, interesting but they are all touched upon and then dropped. Focus goes instead to the “hero,” the bad-guy orphan turned (for reasons we never learn) good. Boring. Oh, and what the hell is going on with the ghost Indian?

down the killer-gang in one last attempt to win the woman he loves? Or is it about the buffalo cowboys trying to make their way in a white man’s land after the civil war? Any of these stories could have been, indeed would have been, interesting but they are all touched upon and then dropped. Focus goes instead to the “hero,” the bad-guy orphan turned (for reasons we never learn) good. Boring. Oh, and what the hell is going on with the ghost Indian?

Speaking of Halt and Catch Fire it’s on AMC and Netflix and also makes my binge-worthy list. It’s about the rise of the personal computer and the internet. The first season was very good. The second season flagged with a bunch of unnecessary and diverting plots about sex, including a bizarre AIDS subplot. It got back on track in the third season, however, and finishes with the wonderful fourth season and the transcendent Goodwill episode.

The Punisher on Netflix. Binge-worthy! Be forewarned, however, this is the most violent of the Marvel superhero shows. Lots of homage here to Dirty Harry, Goodfellas the infamous eye-ball scene from Casino (NSFW and maybe NSFH). The surface plot, guess who the bad guy is?, was boring and predictable but there’s also lots of interesting commentary on war, the bonding of men (hints of fraternal polyandry) and the pull of amoral familism when society seems to be breaking down.

Canada facts of the day

The estimate comes from Canada’s bureau of statistics, which studied marijuana consumption between 1960 and 2015.

The government has promised to research the drug’s affect on the economy and society as it ramps up its plans to legalise cannabis next summer.

The report also found that use has gone up over the years as it has become more popular with adults.

In the 1960s and 1970s cannabis was primarily consumed by young people, according to Statistics Canada.

But in 2015, only 6% of 15-17 year olds smoked cannabis recreationally, compared to two thirds of adults over 25.

Here is the story, via Mark Thorson.

Uber as an ambulance substitute

Using an ambulance to travel to the hospital in an emergency can cost upwards of $1,000 USD. Now research demonstrates that a significant number of people are instead choosing Uber to perform the same service.

The paper – currently being peer reviewed – examines the effect on ambulance usage as Uber was introduced to 766 cities across 43 states. According its findings, even the most conservative estimate shows a seven percent reduction in people traveling via ambulance where the service is available.

Here is the full story, via Jeffrey Deutsch. File under “Even with surge pricing, bending the cost curve.”