Category: Medicine

Big, Fat, Rich Insurance Companies

In my post, Horseshoe Theory: Trump and the Progressive Left, I said:

Trump’s political coalition isn’t policy-driven. It’s built on anger, grievance, and zero-sum thinking. With minor tweaks, there is no reason why such a coalition could not become even more leftist. Consider the grotesque canonization of Luigi Mangione, the (alleged) murderer of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson. We already have a proposed CA ballot initiative named the Luigi Mangione Access to Health Care Act, a Luigi Mangione musical and comparisons of Mangione to Jesus. The anger is very Trumpian.

In that light, consider one of Trump’s recent postings:

THE ONLY HEALTHCARE I WILL SUPPORT OR APPROVE IS SENDING THE MONEY DIRECTLY BACK TO THE PEOPLE, WITH NOTHING GOING TO THE BIG, FAT, RICH INSURANCE COMPANIES, WHO HAVE MADE $TRILLIONS, AND RIPPED OFF AMERICA LONG ENOUGH.

Why are US Clinical Trials so Expensive?

Dave Ricks, CEO of Eli Lilly, speaking on the excellent Cheeky Pint Podcast (hosted by John Collison, sometimes joined by Patrick as in this episode) had the clearest discussion of why US clinical trial costs are so expensive that I have read.

One point is obvious once you hear it: Sponsors must provide high-end care to trial participants–thus because U.S. health care is expensive, US clinical trials are expensive. Clinical trial costs are lower in other countries because health care costs are lower in other countries but a surprising consequence is that it’s also easier to recruit patients in other countries because sponsors can offer them care that’s clearly better than what they normally receive. In the US, baseline care is already so good, at least at major hospital centers where you want to run clinical trials, that it’s more difficult to recruit patients. Add in IRB friction and other recruitment problems, and U.S. trial costs climb fast.

Patrick

I looked at the numbers. So, apparently the median clinical trial enrollee now costs $40,000. The median US wage is $60,000, so we’re talking two thirds. Why and why couldn’t it be a 10th or a hundredth of what it is?David (00:10:50):

Yeah, brilliant question and one we’ve spent a lot of time working on…“Why does a trial cost so much?” Well, we’re taking the sickest slice of the healthcare system that are costing the most. And we’re ingesting them. We’re taking them out of the healthcare system and putting them in a clinical trial. Typically we pay for all care. So we are literally running the healthcare system for those individuals and that is in some ways for control, because you want to have the best standard of care so your experiment is properly conducted and it’s not just left to the whims of hundreds of individual doctors and people in Ireland versus the US getting different background therapies. So you standardize that, that costs money because sort of leveling up a lot of things, but then also in some ways you’re paying a premium to both get the treating physicians and have great care to get the patient. We don’t offer them remuneration, but they get great care and inducement to be in the study because you’re subjecting yourself quite often, not all the case, but to something other than the standard of care, either placebo or this. Or, in more specialized care, often it’s standard care plus X where X could actually be doing harm, not good. So people have to go into that in a blinded way and I guess the consideration is you’ll get the best care.Patrick (00:12:51):

Of the $40,000. How much of that should I look at as inducement and encouragement for the patient and how much should I look at it as the cost of doing things given the regulatory apparatus that exists?David (00:13:02):

The patient part is the level up part and I would say 20, 30% of the cost of studies typically would be this. So you’re buying the best standard of care, you’re not getting something less. That’s medicine costs, you’re getting more testing, you’re getting more visits, and then there is a premium that goes to institutions, not usually to the physician, the institution to pay for the time of everybody involved in it plus something. We read a lot about it in the NIH cuts, the 60% Harvard markup or whatever. There’s something like that in all clinical trials too. Overhead coverage, whatnot. But it’s paying for things that aren’t in the trial.Patrick (00:13:40):

US healthcare is famously the most expensive in the world. Yes. Do you run trials outside the US?David (00:13:44):

Yeah, actually most. I mean we want to actually do more in the US. This is a problem I think for our country. Take cancer care where you think, okay, what’s the one thing the US system’s really good at? If I had cancer, I’d come to the US, that’s definitely true. But only 4% of patients who have cancer in the US are in clinical trials. Whereas in Spain and Australia it’s over 25%.And some of that is because they’ve optimized the system so it’s easier to run and then enroll, which I’d like to get to, people in the trials. But some of it is also that the background of care isn’t as good. So that level up inducement is better for the patient and the physician. Here, the standard’s pretty good, so people are like, “Do I want to do something where there’s extra visits and travel time?” There’s another problem in the US which is, we have really good standards of care but also quite different performing systems and we often want to place our trials in the best performing systems that are famous, like MD Anderson or the Brigham. And those are the most congested with trials and therefore they’re the slowest and most expensive. So there’s a bit of a competition for place that goes on as well.

But overall, I would say in our diabetes and cardiovascular trials, many, many more patients are in our trials outside the US than in and that really shouldn’t be other than cost of the system. And to some degree the tuning of the system, like I mentioned with Spain and Australia toward doing more clinical trials. For instance, here in the US, everywhere you get ethics clearance, we call it IRB. The US has a decentralized system, so you have to go to every system you’re doing a study in. Some countries like Australia have a single system, so you just have one stop and then the whole country is available to recruit those types of things.

Patrick (00:15:31):

You said you want to talk about enrollment?David (00:15:32):

Yeah, yeah. It’s fascinating. So drug development time in the industry is about 10 years in the clinic, a little less right now. We’re running a little less than seven at Lilly, so that’s the optimization I spoke about. But actually, half of that seven is we have a protocol open, that means it’s an experiment we want to run. We have sites trained, they’re waiting for patients to walk in their door and to propose, “Would you like to be in the study?” But we don’t have enough people in the study. So you’re in the serial process, diffuse serial process, waiting for people to show up. You think, “Wow, that seems like we could do better than that. If Taylor Swift can sell at a concert in a few seconds, why can’t I fill an Alzheimer’s study? There seem to be lots of patients.” But that’s healthcare. It’s very tough. We’ve done some interesting things recently to work around that. One thing that’s an idea that partially works now is culling existing databases and contacting patients.Patrick (00:16:27):

Proactive outreach.

See also Chertman and Teslo at IFP who have a lot of excellent material on clinical trial abundance.

Lots of other interesting material in this episode including how Eli Lilly Direct—driven largely by Zepbound—has quickly become a huge pharmacy. The direct-to-consumer model it represents could be highly productive as more drugs for preventing disease are developed. I am not as anti-PBM as Ricks and almost everyone in the industry are but I will leave that for another day.

Here is the Cheeky Pint Podcast main page.

More From Less: Optimizing Vaccine Doses

During COVID, I argued strongly that we should cut the Moderna dose in order to expand supply. In a paper co-authored with Witold Więcek, Michael Kremer and others, we showed that a half dose of Moderna was more effective than a full dose of AstraZenecs and that doubling the effective Moderna supply could have saved many lives.

It’s not just about COVID. My co-author on the COVID paper, Witold Więcek, has found other examples where a failure to run dose optimization trials cost lives:

Take the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine. For years after its introduction, countries administered it as a three-dose series. Then additional evidence emerged; eventually, a single dose proved to be non-inferior. This policy shift, driven by updated World Health Organization (WHO) guidance, has been a game-changer—massively reducing delivery costs while expanding coverage in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). But it took 16 years from regulatory approval to WHO recommendation. Had this change been implemented just five years earlier, the paper estimates that 150,000 lives could have been saved.

Knowing the potential for dose optimization should encourage us to take a closer look at what we can do now. Więcek points to two high-opportunity projects:

- The pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) is already Gavi’s top cost driver, consuming $1 billion of its 2026–2030 budget. But new WHO SAGE guidance, from March 2025, suggests that in countries with consistently high coverage (≥80–90 percent over five years), either one of three shots could be dropped, or each of the three doses can be lowered to 40 percent of the standard dose. While implementation requires sufficient epidemiological surveillance, its cost would be offset by significant savings in vaccine costs: a retrospective analysis suggests that for the 2020–25 period this approach could have led to as much as $250 million in savings.

- New tuberculosis vaccines, currently in phase 2–3 trials, are another high-impact example. Given initial promising results, a future vaccine could prove highly effective, but may also become a significant cost driver for countries and/or Gavi—and optimization may prove highly beneficial both in terms of health and economic value.

Witold’s new paper is here and here is excellent summary blog post from which I have drawn.

Addendum: See also my paper on Bayesian Dose Optimization Trials and from Mike Doherty Particles that enhance mRNA delivery could reduce vaccine dosage and costs.

Incentives matter, and supply is elastic

Now we read that in a Harvard job market paper, by Olivia Zhao with co-author Edward Kong:

Pharmaceutical firms’ incentives to develop new drugs stem from expected profitability. We explore how market exclusivity, a policy that shapes these expectations, influences pharmaceutical innovation. First, we estimate the effects of extending market exclusivity for antibiotics, a drug class where private returns to development historically had not internalized the high social value of new innovation. Using a difference-in-differences approach, we find that a policy that approximately doubled the market exclusivity period for certain antibiotics increased innovative activity. Patent f ilings for antibiotics increased by 47%, and we find suggestive evidence that preclinical studies and phase 3 trial initiations also increased under the policy. Building on these empirical findings, we estimate a structural model of firms’ drug development decisions to predict how market exclusivity extensions of varying lengths would affect innovation in antibiotics and other therapeutic areas. Our reduced form and structural findings suggest that market exclusivity—especially if targeted to high-social-value, low-market-return areas—can be an effective tool for realigning incentives and stimulating innovation, but stress that baseline market size and interactions between market and patent exclusivities affect this policy lever’s impacts.

Here is the paper, I guess for such work, intended for such an audience, one does not refer to history’s greatest villain? And here is their paper on market incentives and antibiotics. Via Nicholas Decker.

“Gender without Children”

What would the lives of women look like if they knew from an early age that they would not have children? Would they make different choices about human capital or early career investments? Would they behave differently in the marriage market? Would they fare better in the labor market? In this paper, we follow 152 women diagnosed with the Mayer-Rokitanski-Kuster-Hauser (MRKH) type I syndrome. This congenital condition, diagnosed at puberty, is characterised by the absence of the uterus in otherwise phenotypically normal 46, XX females. Using granular health registries matched with administrative data from Sweden, we confirm that MRKH is not associated with worse health, nor with differential pre-diagnosis characteristics, and that it has a large negative impact on the probability to ever live with a child. Relative to women from the general population, women with the condition have better educational outcomes, tend to marry and divorce at the same rate, but mate with older men, and hold significantly more progressive beliefs regarding gender roles. The condition has also very large positive effects on earnings and employment. Dynamics reveal that most of this positive effect emerges around the arrival of children in women in the general population, with little difference before. We also find that women with MRKH perform as well as men in the labor market in the long run. Results confirm that “child penalties” on the labor market trajectories of women are large and persistent and that they explain the bulk of the remaining gender gap.

That is from recent work by Tatiana Pazem, with co-authors Camille Landais, Peter Lundberg, Erik Plug & Johan Vikstrom. Tatiana is on the job market from LSE, with her main job market paper being “Pension Reforms and Consumption in Retirement: Evidence from French Transactions and Bank Data.”

The microfoundations of the baby boom?

Between 1936 and 1957, fertility rates in the U.S. increased 62 percent and the maternal mortality rate declined by 93 percent. We explore the effects of changes in maternal mortality rates on white and nonwhite fertility rates during this period, exploiting contemporaneous or lagged changes in maternal mortality at the state-by-year level. We estimate that declines in maternal mortality explain 47-73 percent of the increase in fertility between 1939 and 1957 among white women and 64-88 percent of the increase in fertility among nonwhite women during our sample period.

Here is the full article by Christopher Handy and Katharine Shester, via the excellent Kevin Lewis. Overall, I take this as a negative for the prospect of another, future baby boom? We just cannot make maternity all that much safer, starting from current margins.

Privatizing Law Enforcement: The Economics of Whistleblowing

The False Claims Act lets whistleblowers sue private firms on behalf of the federal government. In exchange for uncovering fraud and bringing the case, whistleblowers can receive up to 30% of any recovered funds. My work on bounty hunters made me appreciate the idea of private incentives in the service of public goals but a recent paper by Jetson Leder-Luis quantifies the value of the False Claims Act.

Leder-Luis looks at Medicare fraud. Because the government depends heavily on medical providers to accurately report the services they deliver, Medicare is vulnerable to misbilling. It helps, therefore, to have an insider willing to spill the beans. Moreover, the amounts involved are very large giving whistleblowers strong incentives. One notable case, for example, involved manipulating cost reports in order to receive extra payments for “outliers,” unusually expensive patients.

On November 4, 2002, Tenet Healthcare, a large investor-owned hospital company, was sued under the False Claims Act for manipulating its cost reports in order to illicitly receive additional outlier payments. This lawsuit was settled in June 2006, with Tenet paying $788 million to resolve these allegations without admission of guilt.

The savings from the defendants alone were significant but Leder-Luis looks for the deterrent effect—the reduction in fraud beyond the firms directly penalized. He finds that after the Tenet case, outlier payments fell sharply relative to comparable categories, even at hospitals that were never sued.

Tenet settled the outlier case for $788 million, but outlier payments were around $500 million per month at the time of the lawsuit and declined by more than half following litigation. This indicates that outlier payment manipulation was widespread… for controls, I consider the other broad types of payments made by Medicare that are of comparable scale, including durable medical equipment, home health care, hospice care, nursing care, and disproportionate share payments for hospitals that serve many low-income patients.

…the five-year discounted deterrence measurement for the outlier payments computed is $17.46 billion, which is roughly nineten times the total settlement value of the outlier whistleblowing lawsuits of $923 million.

[Overall]…I analyze four case studies for which whistleblowers recovered $1.9 billion in federal funds. I estimate that these lawsuits generated $18.9 billion in specific deterrence effects. In contrast, public costs for all lawsuits filed in 2018 amounted to less than $108.5 million, and total whistleblower payouts for all cases since 1986 have totaled $4.29 billion. Just the few large whistleblowing cases I analyze have more than paid for the public costs of the entire whistleblowing program over its life span, indicating a very high return on investment to the FCA.

As an aside, Leder-Luis uses synthetic control but allows the controls to come from different time periods. I’m less enthused by the method because it introduces another free parameter but given the large gains at small cost from the False Claims Act, I don’t doubt the conclusion:

The results of this analysis suggest that privatization is a highly effective way to combat fraud. Whistleblowing and private enforcement have strong deterrence effects and relatively low costs, overcoming the limited incentives for government-conducted antifraud enforcement. A major benefit of the False Claims Act is not just the information provided by the whistleblower but also the profit motive it provides for whistleblowers to root out fraud.

Are the ACA exchanges unraveling?

After all, that is what economists predicted if the mandate was not tightly enforced. Here is the latest reprt:

Premiums for the most popular types of plans sold on the federal health insurance marketplace Healthcare.gov will spike on average by 30 percent next year, according to final rates approved by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and shown in documents reviewed by The Washington Post.

The higher prices — affecting up to 17 million Americans who buy coverage on the federal marketplace — reflect the largest annual premium increases by far in recent years.

Here is the full article.

The MR Podcast: Our Favorite Models, Session 2: The Baumol Effect

On The Marginal Revolution Podcast this week we continue discussing some of our favorite models with a whole episode on the Baumol effect (with a sideline into the Linder effect). I say our favorite models, but the Baumol Effect is not one of Tyler’s favorite models! I thought this was a funny section:

TABARROK: When you look at all of these multiple sectors, the repair sector, repairing of clothing, repairing of shoes, repairing of cars, repairing of people, it’s not an accident that these are all the same thing. Healthcare is the repairing of people. Repair services, in general, have gone up because it’s a very labor-intensive area of the economy. It’s all the same thing. That’s why I like the Baumol effect, because it explains a very wide set of phenomena.

COWEN: A lot of things are easier to repair than they used to be, just to be clear. You just buy a new one.

TABARROK: That’s my point. You just buy a new one.

COWEN: It’s so cheap to buy a new one.

TABARROK: Exactly. The new one is manufactured. That’s the whole point, is the new one takes a lot less labor. The repair is much more labor intensive than the actual production of the good. When you actually produce the good, it’s on a factory floor, and you’ve got robots, and they’re all going through da-da-da-da-da-da-da. Repair services, it’s unique.

COWEN: I think you’re not being subjectivist enough in terms of how you define the service. The service for me, if my CD player breaks, is getting a stream of music again. That is much easier now and cheaper than it used to be. If you define the service as the repair, well, okay, you’re ruling out a lot of technological progress. You can think of just diversity of sources of music as a very close substitute for this narrow vision of repair. Again, from the consumer’s point of view, productivity on “repair” has been phenomenal.

TABARROK: That is a consequence of the Baumol effect, not a denial of the Baumol effect. Because of the Baumol effect, repair becomes much more expensive over time, so people look for substitutes. Yes, we have substituted into producing new goods. It works both ways. The new goods are becoming cheaper to manufacture. We are less interested in repair. Repair is becoming more expensive. We’re more interested in the new goods. That’s a consequence of the Baumol effect.

You can’t just say, “Oh, look, we solved the repair problem by throwing things out. Now we don’t have to worry about repairs.” Yes, that’s because repair became so much more expensive. A shift in relative prices caused people to innovate. I’m not saying that innovation doesn’t happen. One of the reasons that innovation happens is because the relative price of repair services is going up.

COWEN: That’s a minor effect. It’s not the case that, oh, I started listening to YouTube because it became too expensive to repair my CD player. It might be a very modest effect. Mostly, there’s technological progress. YouTube, Spotify, and other services come along, Amazon one-day delivery, whatever else. For the thing consumers care about, which is never what Baumol wanted to talk about. He always wanted to fixate on the physical properties of the goods, like the anti-Austrian he was.

It’s just like, oh, there’s been a lot of progress. It takes the form of networks with very complex capital and labor interactions. It’s very hard to even tease out what is truly capital intensive, truly labor intensive. You see this with the AI companies, all very mixed together. That just is another way of looking at why the predictions are so hard. You can only get the prediction simple by focusing very simply on these nonsubjectivist, noneconomic, physical notions of what the good has to be.

TABARROK: I think there’s too much mood affiliation there, Tyler.

COWEN: There’s not enough Kelvin Lancaster in Baumol.

Here’s the episode. Subscribe now to take a small step toward a much better world: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | YouTube.

The unraveling of Obamacare?

Paul Krugman has a recent post defending the exchange subsidies and tax credits that the Republicans wish to cut, talking with Jonathan Cohn about the “premium apocalypse” (and here). Whether or not one agrees with Krugman normatively, the arguments if anything convince me that Obamacare probably is not financially or politically stable.

To recap some history briefly:

1. Prior to passage, ACA advocates assured us that all three “legs of the stool” were necessary, most of all the mandate, to prevent adverse selection and skyrocketing premia. That argument made sense and was accepted by most economists, whether or not they favored ACA.

2. Obamacare passes by razor-thin margins, with a mandate.

3. The mandate proves extremely unpopular. Whether or not it is efficient, it puts a disproportionate share of the cost burden on other policy purchasers through the exchanges. The Republicans run against ACA and make some big gains.

4. Trump in essence “saves” Obamacare by in essence defusing enforcement of the mandate. The people who hated paying the very high premia could now back out of the system without getting into real trouble. As a result, much of the opposition to Obamacare, and the scare stories about expensive policies, dissipates.

5. Contrary to the predictions of the economists, Obamacare does not collapse. Enough people kept on signing up, perhaps because there is often a fair degree of “positive selection” into insurance coverage. Still, one has to wonder whether this will last.

6. Under the Biden administration, the Democrats support the continuation of premium support, but not with massive enthusiasm. It is expensive, though of course the Democrats did understand this is a centerpiece of Obamacare and they cannot give up on it. If you are calling the current situation a “premium apocalypse,” a lot of money has to be involved.

7. Putting aside the current Trump plans and the government shutdown and concomitant fight, how stable is this budget allocation over time? Is it possible that the economists (including Krugman and David Cutler) were right all along, albeit with a long lag, and the exchanges ultimately cannot work without a mandate? And that the premium support will just get more and more expensive?

It seems to be this scenario, while hardly proven, is really quite possible. One can blame Trump of course, but maybe the allocation no longer is sustainable over the medium term?

During the ACA debates, Megan McArdle frequently made the point that such a big policy passed by such small margins could not so easily last. A lot of people wanted to look past that observation, but was she so wrong?

Addendum: By the way, how are we supposed to pay for all of this? Repealing the recent Trump tax cuts and raising taxes on the rich doesn’t seem to come close to bringing the budget into balance. Endorse a VAT if you wish, but then do so! And let us have that debate. In the meantime everyone is just playing games with us.

More corruption in the Harvard leadership

Harvard School of Public Health Dean Andrea A. Baccarelli received at least $150,000 to testify against Tylenol’s manufacturer in 2023 — two years before he published research used by the Trump administration to link the drug to autism, a connection experts say is tenuous at best.

Baccarelli served as an expert witness on behalf of parents and guardians of children suing Johnson & Johnson, the manufacturer of Tylenol at the time. U.S. District Court Judge Denise L. Cote dismissed the case last year due to a lack of scientific evidence, throwing out Baccarelli’s testimony in the process.

“He cherry-picked and misrepresented study results and refused to acknowledge the role of genetics in the etiology” of autism spectrum disorder or ADHD, Cote wrote in her decision, which the plaintiffs have since appealed.

Here is more from The Crimson.

AI and the FDA

Dean Ball has an excellent survey of the AI landscape and policy that includes this:

The speed of drug development will increase within a few years, and we will see headlines along the lines of “10 New Computationally Validated Drugs Discovered by One Company This Week,” probably toward the last quarter of the decade. But no American will feel those benefits, because the Food and Drug Administration’s approval backlog will be at record highs. A prominent, Silicon Valley-based pharmaceutical startup will threaten to move to a friendlier jurisdiction such as the United Arab Emirates, and they may in fact do it.

Eventually, I expect the FDA and other regulators to do something to break the logjam. It is likely to perceived as reckless by many, including virtually everyone in the opposite party of whomever holds the White House at the time it happens. What medicines you consume could take on a techno-political valence.

Agreed—but the nearer-term upside is repurposing. Once a drug has been FDA approved for one use, physicians can prescribe it for any use. New uses for old drugs are often discovered, so the off-label market is large. The key advantage of off-label prescribing is speed: a new use can be described in the medical literature and physicians can start applying that knowledge immediately, without the cost and delay of new FDA trials. When the RECOVERY trial provided evidence that an already-approved drug, dexamethasone, was effective against some stages of COVID, for example, physicians started prescribing it within hours. If dexamethasone had had to go through new FDA-efficacy trials a million people would likely have died in the interim. With thousands of already approved drugs there is a significant opportunity for AI to discover new uses for old drugs. Remember, every side-effect is potentially a main effect for a different condition.

On Ball’s main point, I agree: there is considerable room for AI-discovered drugs, and this will strain the current FDA system. The challenge is threefold.

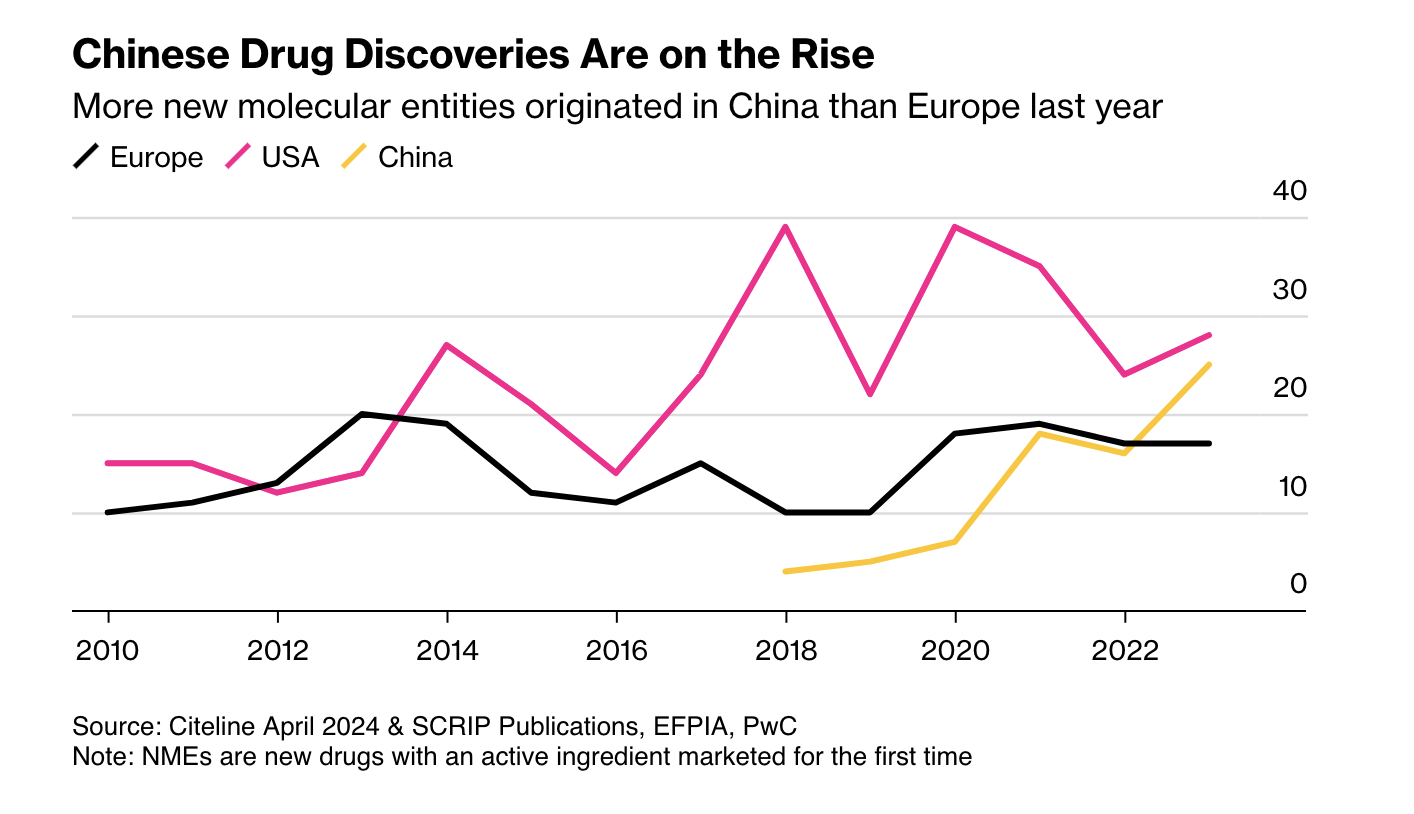

First, as Ball notes, more candidate drugs at lower cost means other regulators may become competitive with the FDA. China is the obvious case: it is now large and wealthy enough to be an independent market, and its regulators have streamlined approvals and improved clinical trials. More new drugs now emerge from China than from Europe.

Second, AI pushes us toward rational drug design. RCTs were a major advance, but they are in some sense primitive. Once a mechanic has diagnosed a problem, the mechanic doesn’t run a RCT to determine the solution. The mechanic fixes the problem! As our knowledge of the body grows, medicine should look more like car repair: precise, targeted, and not reliant on averages.

Closely related is the rise of personalized medicine. As I wrote in A New FDA for the Age of Personalized, Molecular Medicine:

Each patient is a unique, dynamic system and at the molecular level diseases are heterogeneous even when symptoms are not. In just the last few years we have expanded breast cancer into first four and now ten different types of cancer and the subdivision is likely to continue as knowledge expands. Match heterogeneous patients against heterogeneous diseases and the result is a high dimension system that cannot be well navigated with expensive, randomized controlled trials. As a result, the FDA ends up throwing out many drugs that could do good.

RCTs tell us about average treatment effects, but the more we treat patients as unique, the less relevant those averages become.

AI holds a lot of promise for more effective, better targeted drugs but the full promise will only be unlocked if the FDA also adapts.

Girls improve student mental health

Using individual-level data from the Add Health surveys, we leverage idiosyncratic variation in gender composition across cohorts within the same school to examine whether being exposed to a higher share of female peers affects mental health and school satisfaction. We find that being exposed to a higher proportion of female peers, despite only improving school satisfaction for boys, improves mental health for both boys and girls. The benefits are greater among boys of low socioeconomic backgrounds, who would otherwise be more likely to be exposed to violent and disruptive peers. We find suggestive evidence that the mechanisms driving our findings are consistent with stronger school friendships for boys and better self-image and grades for girls.

That is from a new NBER working paper by Monica Deza and Maria Zhu.

Is it the phones?

Or perhaps we should just credit Sydney Sweeney? That is from Chris Said.

One look at negative emotional contagion

This paper studies how peers’ genetic predisposition to depression affects own mental health during adolescence and early adulthood using data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health). I exploit variation within schools and across grades in same-gender grademates’ average polygenic score—a linear index of genetic variants—for major depressive disorder (the MDD score). An increase in peers’ genetic risk for depression has immediate negative impacts on own mental health. A one standard deviation increase in same-gender grademates’ average MDD score significantly increases the probability of being depressed by 1.9 and 3.8 percentage points for adolescent girls (a 7.2% increase) and boys (a 25% increase), respectively. The effects persist into adulthood for females, but not males. I explore several potential mechanisms underlying the effects and find that an increase in peers’ genetic risk for depression in adolescence worsens friendship, increases substance use, and leads to lower socioeconomic status. These effects are stronger for females than males. Overall, the results suggest that there are important social-genetic effects in the context of mental health.

That is from a recent paper by Yeongmi Jeong, via the excellent Kevin Lewis.