Category: Medicine

Where are the trillion dollar biotech companies?

In today’s market, even companies with multiple approved drugs can trade below their cash balances. Given this, it is truly perplexing to see AI-biotechs raise mega-rounds at the preclinical stage – Xaira with a billion-dollar seed, Isomorphic with $600M, EvolutionaryScale with $142M, and InceptiveBio with $100M, to name a few. The scale and stage of these rounds reflect some investors’ belief that AI-biology pairing can bend the drug discovery economics I described before.

To me, the question of whether AI will be helpful in drug discovery is not as interesting as the question of whether AI can turn a 2-billion-dollar drug development into a 200-million-dollar drug development, or whether 10 years to approve a drug can become 5 years to approve a drug. AI will be used to assist drug discovery in the same way software has been used for decades, and, given enough time, we know it will change everything [4]. But is “enough time” 3 years or half a century?

One number that is worth appreciating is that 80% of all costs associated with bringing a drug to market come from clinical-stage work. That is, if we ever get to molecules designed and preclinically validated in under 1 year, we’ll be impacting only a small fraction of what makes drug discovery hard. This productivity gain cap is especially striking given that the majority of the data we can use to train models today is still preclinical, and, in most cases, even pre-animal. A perfect model predictive of in vitro tox saves you time on running in vitro tox (which is less than a few weeks anyway!), doesn’t bridge the in vitro to animal translation gap, and especially does not affect the dreaded animal-to-human jump. As such, perfecting predictive validity for preclinical work is the current best-case scenario for the industry. Though we don’t have a sufficient amount and types of data to solve even that.

Here is the full and very interesting essay, from the excellent Lada Nuzhna.

Decker and KingoftheCoast on single payer health insurance

Here is the conclusion of the piece:

To reiterate, the key point in this piece is that high administrative costs in US healthcare are unlikely to represent “do-nothing waste.” Some of the purported costs are entirely fake. To include them in the possible savings of single payer shows either ignorance or dishonesty. Some of the costs are to prevent waste and fraud, which should be paid by Medicare now (although they are not). Of what is left, the cost of duplication pales in comparison to the plausible benefits of choice and competition in health insurance. When you put all of these together, the case for single-payer is nonexistent. A better system would be to subsidize those who are too poor to pay, scrap the government health insurance providers and the VA, remove the employer tax deduction, and allow providers to compete.

Here is the full piece, excellent work.

Do not forget

Estimating real-world vaccine effectiveness is vital to assessing the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination program and informing the ongoing policy response. However, estimating vaccine effectiveness using observational data is inherently challenging because of the nonrandomized design and potential for unmeasured confounding. We used a regression discontinuity design to estimate vaccine effectiveness against COVID-19 mortality in England using the fact that people aged 80 years or older were prioritized for the vaccine rollout. The prioritization led to a large discrepancy in vaccination rates among people aged 80–84 years compared with those aged 75–79 at the beginning of the vaccination campaign. We found a corresponding difference in COVID-19 mortality but not in non-COVID-19 mortality, suggesting that our approach appropriately addressed the issue of unmeasured confounding factors. Our results suggest that the first vaccine dose reduced the risk of COVID-19 death by 52.6% (95% confidence limits: 15.7, 73.4) in those aged 80 years, supporting existing evidence that a first dose of a COVID-19 vaccine had a strong protective effect against COVID-19 mortality in older adults. The regression discontinuity model’s estimate of vaccine effectiveness is only slightly lower than those of previously published studies using different methods, suggesting that these estimates are unlikely to be substantially affected by unmeasured confounding factors.

From Charlotte Bermingham, et.al. There is plenty of other research yielding broadly similar conclusions. The Covid vaccines saved millions of lives, well over two million lives even from a conservative estimate.

For the pointer I thank Alex T.

Dean Ball on state-level AI laws

He is now out of government and has resumed writing his Substack. Here is one excerpt from his latest:

Several states have banned (see also “regulated,” “put guardrails on” for the polite phraseology) the use of AI for mental health services. Nevada, for example, passed a law (AB 406) that bans schools from “[using] artificial intelligence to perform the functions and duties of a school counselor, school psychologist, or school social worker,” though it indicates that such human employees are free to use AI in the performance of their work provided that they comply with school policies for the use of AI. Some school districts, no doubt, will end up making policies that effectively ban any AI use at all by those employees. If the law stopped here, I’d be fine with it; not supportive, not hopeful about the likely outcomes, but fine nonetheless.

But the Nevada law, and a similar law passed in Illinois, goes further than that. They also impose regulations on AI developers, stating that it is illegal for them to explicitly or implicitly claim of their models that (quoting from the Nevada law):

(a) The artificial intelligence system is capable of providing professional mental or behavioral health care;

(b) A user of the artificial intelligence system may interact with any feature of the artificial intelligence system which simulates human conversation in order to obtain professional mental or behavioral health care; or

(c) The artificial intelligence system, or any component, feature, avatar or embodiment of the artificial intelligence system is a provider of mental or behavioral health care, a therapist, a clinical therapist, a counselor, a psychiatrist, a doctor or any other term commonly used to refer to a provider of professional mental health or behavioral health care.

First there is the fact that the law uses an extremely broad definition of AI that covers a huge swath of modern software. This means that it may become trickier to market older machine learning-based systems that have been used in the provision of mental healthcare, for instance in the detection psychological stress, dementia, intoxication, epilepsy, intellectual disability, or substance abuse (all conditions explicitly included in Nevada’s statutory definition of mental health).

But there is something deeper here, too. Nevada AB 406, and its similar companion in Illinois, deal with AI in mental healthcare by simply pretending it does not exist. “Sure, AI may be a useful tool for organizing information,” these legislators seem to be saying, “but only a human could ever do mental healthcare.”

And then there are hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of Americans who use chatbots for something that resembles mental healthcare every day. Should those people be using language models in this way? If they cannot afford a therapist, is it better that they talk to a low-cost chatbot, or no one at all? Up to what point of mental distress? What should or could the developers of language models do to ensure that their products do the right thing in mental health-related contexts? What is the right thing to do?

The State of Nevada would prefer not to think about such issues. Instead, they want to deny that they are issues in the first place and instead insist that school employees and occupationally licensed human professionals are the only parties capable of providing mental healthcare services (I wonder what interest groups drove the passage of this law?).

Free the Patient: A Competitive-Federalism Fix for Telemedicine

During the pandemic, many restrictions on telemedicine were lifted, making it far easier for physicians to treat patients across state lines. That window has largely closed. Today, unless a doctor is separately licensed in a patient’s state—or the states have a formal agreement—remote care is often illegal. So if you live in Virginia and want a second opinion from a Mayo Clinic physician in Florida, you may have to fly to Florida, unless that Florida physician happens to hold a Virginia license.

The standard framing says this is a problem of physician licensing. That leads directly to calls for interstate compacts or federalizing medical licensure. Mutual recognition is good. Driver’s licenses are issued by states but are valid in every state. No one complains that Florida’s regime endangers Virginians. But mutual recognition or federal licensing is not the only solution nor the only way to think about this issue.

The real issue isn’t who licenses doctors. It’s that patients are forbidden from choosing a licensed doctor in another state. We can keep state-level licensing, but free the patient. Let any American consult any physician licensed in any state. That’s competitive federalism—no compacts, no federal agency, just patient choice.

A close parallel comes from credit markets. After Marquette Nat. Bank v. First of Omaha (1978), host states could no longer block their residents from using credit cards issued by national banks chartered elsewhere. A Virginian can legally borrow on a South Dakota credit card at South Dakota’s rates. Nothing changed about South Dakota’s licensing; what changed was the prohibition on choice.

Consider Justice Brennan’s argument in this case:

“Minnesota residents were always free to visit Nebraska and receive loans in that state.” It hadn’t been suggested that Minnesota’s laws would apply in that instance, he added. Therefore, they shouldn’t be applied just because “the convenience of modern mail” allowed Minnesotans to get credit without having to visit Nebraska.

Exactly analogously, everyone agrees that Virginia residents are free to visit Florida and be treated by Florida physicians. No one suggests that Virginia’s laws should follow VA residents to Florida. Therefore, VA’s laws shouldn’t be applied just because the convenience of modern online tools allow Virginians to get medical advice and consultation without having to visit Florida.

In short, patients should be allowed to choose physicians as easily as borrowers choose banks.

What to Watch (or Not): Ballard, Perfect Days, Billy Joel

Ballard (Amazon Prime) — I liked Bosch, so I had high hopes for this spinoff. The core premise—a team of misfits solving cold cases—is solid enough but the writing is unimaginative and lazy. In one scene, Ballard is told she needs to get a confession. We expect clever interrogation tactics. Instead, she walks in and bluntly asks, “Did you shoot Yulia Kravetz?”

Maggie Q is charismatic but the writers don’t write for her. She’s exceptionally slim, for example, yet the show repeatedly asks us to believe she can physically overpower men twice her size. I have no problem with that in a superhero movie but it’s off putting in a show that pretends to be grounded and gritty. If you’re casting someone with that physique, write her as sharper, more cunning, more insightful—not as a female stand-in for macho Bosch.

Maggie Q is charismatic but the writers don’t write for her. She’s exceptionally slim, for example, yet the show repeatedly asks us to believe she can physically overpower men twice her size. I have no problem with that in a superhero movie but it’s off putting in a show that pretends to be grounded and gritty. If you’re casting someone with that physique, write her as sharper, more cunning, more insightful—not as a female stand-in for macho Bosch.

Worst of all is the ending: a killer reveal that comes out of nowhere, with no foreshadowing or internal logic. The writers don’t understand the difference between a twist and a cheat. Disappointing.

Perfect Days (Hulu, Amazon) — a 2023 Wim Wenders film that won the award at Cannes for “works of artistic quality which witnesses to the power of film to reveal the mysterious depths of human beings through what concerns them, their hurts and failings as well as their hopes.” The film follows the life of Hirayama (Kōji Yakusho, who won at Cannes for best actor) as he cleans public toilets in Tokyo’s Shibuya district. You will not be surprised to learn that the movie proceeds slowly. The toilets and the cleaning are the most interesting part of the first hour! I say this not as critique–I liked Perfect Days and the toilets really are interesting–only to illustrate the kind of movie that it is.

It helps to know the following from a useful Sean Burns review:

Komorebi is a Japanese word for the dancing shadow patterns created by sunlight shining through the rustling leaves of trees. There’s no equivalent term in English, and it’s tough to imagine any American caring enough to come up with one. But every afternoon on his lunch break, Hirayama (Koji Yakusho) takes a picture of the komorebi from his favorite park bench using an old Olympus film camera. Back at his apartment, he’s got boxes and boxes of black-and-white photos of the same spot, every one of them unique. Subtle shifts of the light and swaying branches in the breeze make similar snapshots strikingly different every time. Indeed, the whole concept behind komorebi is that it can exist only in a moment, never to be repeated. “Next time is next time,” Hirayama’s fond of saying, “Now is now.”

Although I would disagree with Burns slightly because there is an English term for something related to komorebi and that is crown shyness, the phenomena where trees grow in such a way that their branches keep from touching one another creating a canopy of closeness yet also distance. Indeed, I would argue that crown shyness expresses more of what the movie is about than komorebi.

A key question that divides reviewers is whether Hirayama is happy or content. The standard interpretation is that he has found, as Davis puts it, “beauty in the routine,” stopping to smell the roses. Yes, that is one aspect, but the routine is also a narcotic for the lost. Hirayama is estranged from his family. Barkeeps like him but all his relationships are superficial. He plays a game with a “friend” he never meets—distance and disconnection are everywhere.. In two scenes he finds meaning and joy in looking after a child but in both these scenes the child’s mother quickly rips the child away. Hirayama’s work partner disappears in the second half of the film. He almost makes connections with three women but in each case, crown shyness intervenes. He takes pride in his work but is operating well below his ability. He is isolated, alone, and without someone else to share a life, he is incomplete.

There are great scenes and music in Perfect Days, including a beautiful scene in which a Japanese hostess (Sayuri Ishikawa) sings House of the Rising Sun.

Billy Joel: And So It Goes (HBO) — 52nd Street was one of my favorite albums as a youth and it was fun to revisit his career. Billy Joel’s first wife, Elizabeth Weber, was the muse for many of his early songs including Big Shot and Stiletto:

She cuts you hard, she cuts you deepShe’s got so much skillShe’s so fascinatingThat you’re still there waitingWhen she comes back for the killYou’ve been slashed in the faceYou’ve been left there to bleedYou want to run awayBut you know you’re gonna stay‘Cause she gives you what you need

She is indeed, fascinating! Wow. Even today, she comes across as formidable.

I thought a lot about genetics while watching And So It Goes. Joel’s father was a classical musician, though his only notable comment on Billy’s playing was to knock him unconscious for taking too much liberty with a piece. The father left when Billy was eight. Not much nurture. Years later, they reunite in Vienna—where Joel discovers he has a half-brother, Alexander Joel, a successful pianist and conductor.

Joel grew up poor, but his paternal grandfather had been a wealthy Jewish businessman in Germany until the Nazis forced him out. His mother, Rosalind, was also musical, but her primary inheritance may have been bipolar disorder. Joel’s mental health struggles are never explicitly named in the documentary, but the signs are everywhere: an early suicide attempt, alcoholism, repeated motorcycle and car crashes of a self-destructive nature. The emotional cycles also help explain the pattern of intense, short-lived marriages to beautiful and accomplished women—Weber, Christie Brinkley, Katie Lee, and Alexis Roderick. In his highs, he was irresistible. In his lows, unbearable. He goes to extremes.

Critics didn’t always love Joel’s music, but his catalog has become part of the American songbook. Proof of something Tyler and I often discuss, the power of simply keeping going.

Design Your Own Rug!

For my wedding anniversary, I designed and had hand-woven in Afghanistan a rug for my microbiologist wife. The rug mixes traditional Afghanistan designs with some scientific elements including Bunsen burners, test tubes, bacterial petri dishes and other elements.

I started with several AI designs, such as that shown below, to give the weavers an idea of what I was looking for. Some of the AI elements were muddled and very complex and so we developed a blueprint over a few iterations. The blueprint was very accurate to the actual rug.

I am very pleased with the final product. The wool is of high quality, deep and luxurious, and the design is exactly what I intended. My wife loves the rug and will hang it at her office. The price was very reasonable, under $1000. I also like that I employed weavers in a small village in Northern Afghanistan. The whole process took about 6 months.

You can develop your own custom rug from Afghanu Rugs. Tell them Alex sent you. Of course, they also have many beautiful traditional designs. You can even order my design should you so desire!

A household expenditure approach to measuring AI progress

Often researchers focus on the capabilities of AI models, for instance what kinds of problems they might solve. Or how they might boost productivity growth rates. But a different question is to ask how they might lower cost of living for ordinary Americans. And while I am optimistic about the future prospects and powers of AI models, on that particular question I think progress will be slow, mostly though through no fault of the AIs.

If you consider a typical household budget, some of the major categories might be:

A. Rent and home purchase

B. Food

C. Health care

D. Education

Let us consider each in turn. Do note that in the longer run AI will do a lot to accelerate and advance science. But in the next five years, most of those advances may not be so visible or available. And so I will focus on some budgetary items in the short run:

A. When it comes to rent, a lot of the constraints are on the supply side. So even very powerful AI will not alleviate those problems. In fact strong AI could make it more profitable to live near other talented people, which could raise a lot of rents. Real wages for the talented would go up too, still I would not expect rents to fall per se.

Strong AI might make it easier to live say in Maine, which would involve a de facto lowering of rents, even if no single rental price falls. Again, maybe.

B. When it comes to food, in some long run AI will genetically engineer better and stronger crops, which in time will be cheaper. We will develop better methods of irrigation, better systems for trading land, better systems for predicting the weather and protecting against storms, and so on. Still, I observe that agricultural improvements (whether AI-rooted or not) can spread very slowly. A lot of rural Mexico still does not use tractors, for instance.

So I can see AI lowering the price of food in twenty years, but in the meantime a lot of real world, institutional, legal, and supply side constraints and bottlenecks will bind. In the short run, greater energy demands could well make food more expensive.

C. When it comes to health care, I expect all sorts of fabulous new discoveries. I am not sure how rapidly they will arrive, but at some point most Americans will die of old age, if they survive accidents, and of course driverless vehicles will limit some of those too. Imagine most people living to the age of 97, or something like that.

In terms of human welfare, that is a wonderful outcome. Still, there will be a lot more treatments, maybe some of them customized for you, as is the case with some of the new cancer treatments. Living to 97, your overall health care expenses probably will go up. It will be worth it, by far, but I cannot say this will alleviate cost of living concerns. It might even make them worse. Your total expenditures on health care are likely to rise.

D. When it comes to education, the highly motivated and curious already learn a lot more from AI and are more productive. (Much of those gains, though, translate into more leisure time at work, at least until institutions adjust more systematically.). I am not sure when AI will truly help to motivate the less motivated learners. But I expect not right away, and maybe not for a long time. That said, a good deal of education is much cheaper right now, and also more effective. But the kinds of learning associated with the lower school grades are not cheaper at all, and for the higher levels you still will have to pay for credentialing for the foreseeable future.

In sum, I think it will take a good while before AI significantly lowers the cost of living, at least for most people. We have a lot of other constraints in the system. So perhaps AI will not be that popular. So the AIs could be just tremendous in terms of their intrinsic quality (as I expect and indeed already is true), and yet living costs would not fall all that much, and could even go up.

The Rising Cost of Child and Pet Day Care

Everyone talks about the soaring cost of child care (e.g. here, here and here), but have you looked at the soaring cost of pet care? On a recent trip, it cost me about $82 per day to board my dog (a bit less with multi-day discounts). And no, that is not high for northern VA and that price does not include any fancy options or treats! Doggie boarding costs about about the same as staying in a Motel 6.

Many explanations have been offered for rising child care costs. The Institute for Family Studies, for example, shows that prices rise with regulations like “group sizes, child-to-staff ratios, required annual training hours, and minimum educational requirements for teachers and center directors.” I don’t deny that regulation raises prices—places with more regulation have higher costs—but I don’t think that explains the slow, steady price increase over time. As with health care and education, the better explanation is the Baumol effect, as I argued in my book (with Helland) Why Are the Prices So Damn High?

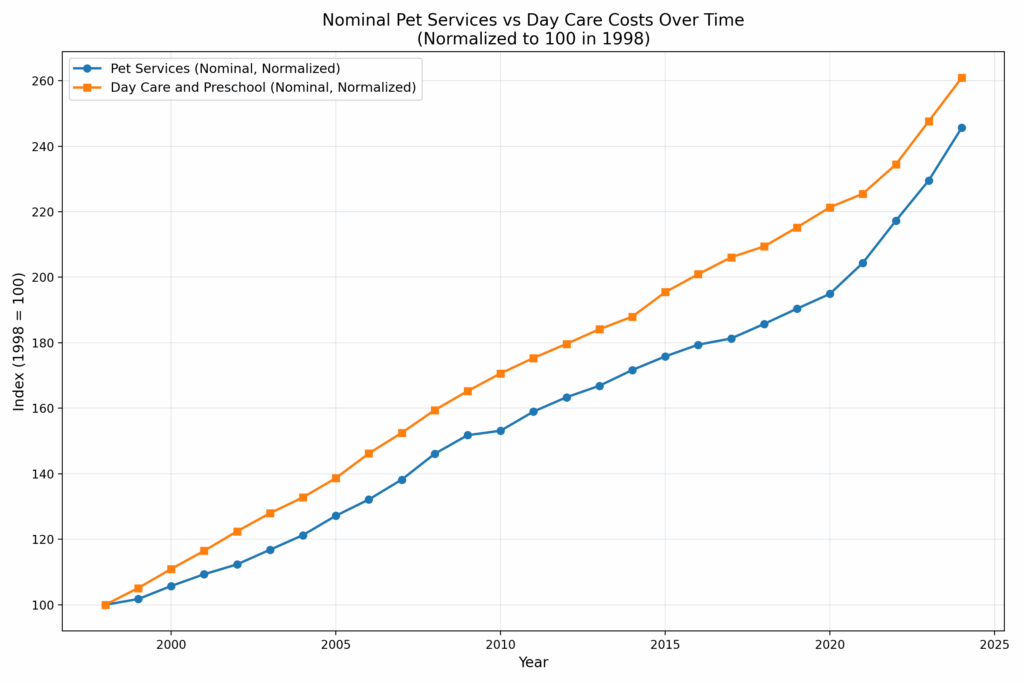

Pet care is less regulated than child care, but it too is subject to the Baumol effect. So how do price trends compare? Are they radically different or surprisingly similar? Here are the two raw price trends for pet services (CUUR0000SS62053) and for (child) Day care and preschool (CUUR0000SEEB03). Pet services covers boarding, daycare, pet sitting, walking, obedience training, grooming but veterinary care is excluded from this series so it is comparable to that for child care.

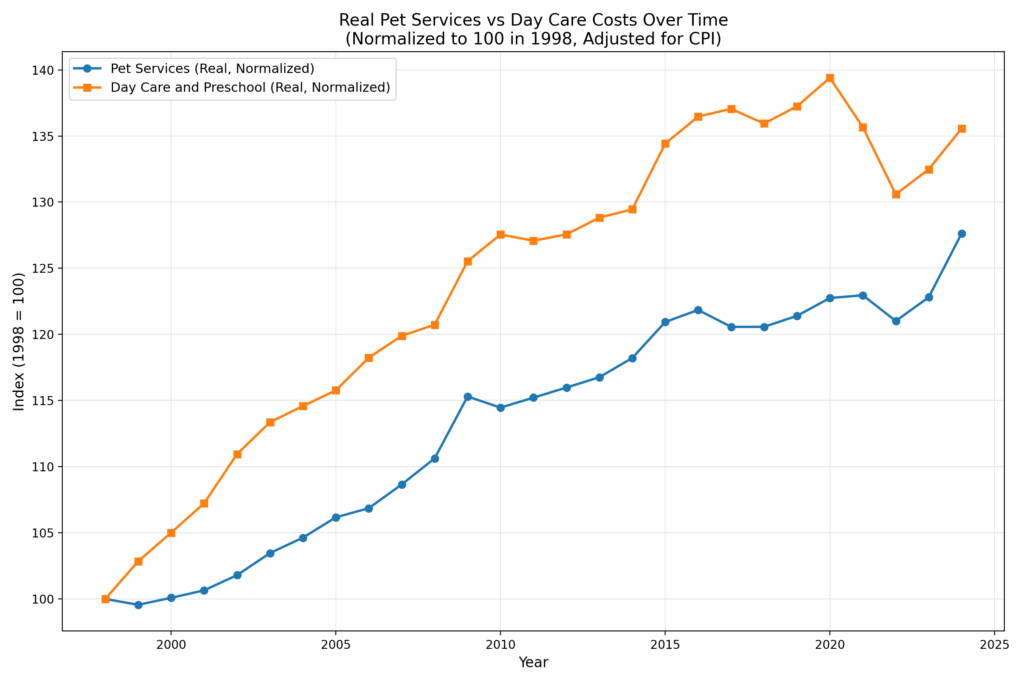

As you can see, the trends are nearly identical, with child care rising only slightly faster than pet care over the past 26 years. Of course, both trends include general inflation, which visually narrows the gap. When we normalize to the overall CPI, we get the following:

Over 26 years, the real (relative) price of Day Care and Preschool has increased 36%, while Pet Services have risen 28%. If regulation doesn’t explain the rise in pet care costs–and it probably doesn’t–then regulation probably doesn’t explain the rise in child care costs either. After all, child and pet care are very similar goods!

The similar rise in the price of child day care and pet day care/boarding is consistent with Is American Pet Health Care (Also) Uniquely Inefficient? by Einav, Finkelstein and Gupta, who find that spending on veterinary care is rising at about the same rate as spending on human health care. Since the regulatory systems of pet and human health care are very different this suggests that the fundamental reason for rising health care isn’t regulation but rising relative prices and increasing incomes (fyi this is also an important reason why Americans spend more on health care than Europeans).

Thus, my explanation for rising prices in child care and pet care is that productivity is increasing in other industries more than in the care industries which means that over time we must give up more of other goods to get child and pet care. In short, if productivity in other sectors rises while child/pet care productivity stays flat, relative prices must rise. Another way to put this is that to retain workers, wages in stagnant-productivity sectors must rise to match those in (equally labor-skilled) high-productivity sectors. That means paying more for the same level of care, simply to keep the labor force from leaving

But rising productivity in other sectors is good! Thus, I always refer to the Baumol effect rather than the “cost disease” because higher prices are not bad when they reflect changes in relative prices. As with education and health care the rising price of child and pet care isn’t a problem for society as whole. We are richer and can afford more of all goods. It can be a problem, however, for people who consume more than the average quantities of the service-sector goods and people who have lower than average wage gains. So what can we do? Redistribution is one possibility.

If we focus on the prices, the core problem is that care work is labor-intensive and labor has a high opportunity cost. One solution is to lower the opportunity cost of that labor. Low-skill immigration helps: when lower-wage workers take on support roles, higher-wage workers can focus on higher-value tasks. As I’ve put it, “The immigrant who mows the lawn of the nuclear physicist indirectly helps to unlock the secrets of the universe.” Same for the immigrant who provides boarding for the pets of the nuclear physicist.

Another solution is capital substitution—automation, AI, better tools. But care jobs resist mechanization; that’s part of why productivity growth is so slow in these sectors. Still, the basic truth remains: if we want more affordable day care—for kids or pets—we need to use less of what’s expensive: skilled labor. That means either importing more people to do the work, or investing harder in ways to do it with fewer hands.

Horseshoe Theory: Trump and the Progressive Left

Many of Trump’s signature policies overlap with those of the American progressive left—e.g. tariffs, economic nationalism, immigration restrictions, deep distrust of elite institutions, and an eagerness to use the power of the state. Trump governs less like Reagan, more like Perón. As Ryan Bourne notes, this ideological convergence has led many on the progressive left to remain silent or even tacitly support Trump policies, particularly on trade.

“[P]rogressive Democrats like Senator Elizabeth Warren have chosen to shift blame for Trump’s tariff-driven price hikes onto large businesses. Last week, they dusted off—and expanded—their pandemic-era Price Gouging Prevention Act. While bemoaning Trump’s ‘chaotic’ on-off tariffs, their real ire remains reserved for ‘greedy corporations,’ supposedly exploiting trade policy disruption to pad prices beyond what’s needed to ‘cover any cost increases.’

…The Democrats’ 2025 gouging bill is broader than ever, creating a standing prohibition against ‘grossly excessive’ price hikes—loosely suggested at anything 20 percent above the previous six-month average—but allowing the FTC to pick its price caps ‘using any metric it deems appropriate.’

…Instead of owning the pricing fallout from his trade wars, President Trump can now point to Democratic cries of ‘corporate greed’ and claim their proposed FTC crackdown proves that it’s businesses—not his tariffs—to blame for higher prices.

If these progressives have their way, the public debate flips from ‘tariffs raise prices’ to ‘the FTC must crack down on corporate greed exploiting trade policy reform,’ with Trump slipping off the hook.”

Trump’s political coalition isn’t policy-driven. It’s built on anger, grievance, and zero-sum thinking. With minor tweaks, there is no reason why such a coalition could not become even more leftist. Consider the grotesque canonization of Luigi Mangione, the (alleged) murderer of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson. We already have a proposed CA ballot initiative named the Luigi Mangione Access to Health Care Act, a Luigi Mangione musical and comparisons of Mangione to Jesus. The anger is very Trumpian.

A substantial share of voters on the left and the right increasingly believe that markets are rigged, globalism is suspect, and corporations are the real enemy. Trump adds nationalist flavor; progressives bring the regulatory hammer. The convergence of left and right in attacking classical liberalism– open markets, limited government, pluralism and the basic rules of democratic compromise–is what worries me the most about contemporary politics.

Someday I want to see the regressions

Each infant born from the procedure carries DNA from a man and two women. It involves transferring the nucleus from the fertilised egg of a woman carrying harmful mitochondrial mutations into a donated egg from which the nucleus has been removed.

For some carriers this is the only option because conventional IVF does not produce enough healthy embryos to use after pre-implantation diagnosis.

The researchers consistently reject the popular term “three-parent babies”, said Turnbull, “but it doesn’t make a scrap of difference.”

Here is more from Clive Cookson at the FT. From Newcastle. And here is some BBC coverage.

The Role of Blood Plasma Donation Centers in Crime Reduction

The United States is one of the few OECD countries to pay individuals to donate blood plasma and is the most generous in terms of remuneration. The opening of a local blood plasma center represents a positive, prospective income shock for would-be donors. Using detailed data on the location of blood plasma centers in the US and two complementary difference-indifferences research designs, we study the impact of these centers on crime outcomes. Our findings indicate that the opening of a plasma center in a city leads to a 12% drop in the crime rate, an effect driven primarily by property and drug-related offenses. A within-city design confirms these findings, highlighting large crime drops in neighborhoods close to a newly opened plasma center. The crime-reducing effects of plasma donation income are particularly pronounced in less affluent areas, underscoring the financial channel as the primary mechanism behind these results. This study further posits that the perceived severity of plasma center sanctions against substance use, combined with the financial channel, significantly contributes to the observed decline in drug possession incidents.

That is from a new paper by Brendon McConnell and Mariyana Zapryanova. Via the excellent Kevin Lewis.

Blame Canada! Measles Edition

Polimath has a good post on measles. The recent spike in U.S. cases has drawn alarm. As the New York Times reports:

There have now been more measles cases in 2025 than in any other year since the contagious virus was declared eliminated in the United States in 2000, according to new data released Wednesday by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The grim milestone represents an alarming setback for the country’s public health and heightens concerns that if childhood vaccination rates do not improve, deadly outbreaks of measles — once considered a disease of the past — will become the new normal.

But as Polimath notes, U.S. vaccination rates remain above 90% nationally. The problem isn’t broad domestic anti-vax sentiment but rather concentrated gaps in coverage, often within insular religious communities. These local shortfalls do explain how outbreaks spread once they begin—but how do they begin in the first place, given these communities are islands within a largely vaccinated country? Polimath says blame Canada! (and Mexico!)

The greater concern in my mind is not the problem of low measles vaccination coverage in the United States, but among our immediate neighbors. In Ontario, the MMR vaccination rate among 7-year-olds is under 70%. As in the examples above, this rate seems to be particularly low “in specific communities”, whatever that is supposed to mean. This has resulted in the ongoing spread of measles such that Ontario’s measles infection rate is 40 times higher than the United States. Canada officially “eliminated” measles in 1998. But with vaccine rates as low as they are, it seems like Canada is at risk for losing that “elimination” status and becoming an international source for measles.

Similarly, Mexico is having a measles outbreak that is substantially worse than the US outbreak. Importantly, the Mexican outbreak has been the worst in the Chihuahua province (over 3,000 cases), which borders Texas and New Mexico.

I’m less interested in blame than in the useful reminder that not all politics is American politics. Vaccination rates have dipped worldwide and not in response to U.S. politics or RFK Jr. In fact, despite RFK Jr. the U.S. is doing better than some of its North American and European peers. Outbreaks here may be triggered by cross-border exposure, not failures in U.S. public health alone. Not all politics is American—and not all American outcomes are made in America.

Hat tip: the excellent Stephen Landry.

GAVI’s Ill-Advised Venture Into African Industrial Policy

GAVI, the Vaccine Alliance has saved millions of lives by delivering vaccines to the world’s poorest children at remarkably low cost. It’s frankly grotesque that RFK Jr. cites “safety” as a reason to cut funding—when the result of such cuts will be more children dying from preventable diseases. Own it.

You can find plenty of RFK Jr. criticism elsewhere, however, and GAVI is not above criticism. Thus, precisely because GAVI’s mission is important, I want to focus on a GAVI project that I think is ill-motivated and ill-advised, GAVI’s African Vaccine Manufacturing Accelerator (AVMA).

The motivation behind the AVMA is to “accelerate the expansion of commercially viable vaccine manufacturing in Africa” to overcome “vaccine inequity” as illustrated during the COVID crisis. The problem with this motivation is that most of Africa’s delay in receiving COVID vaccines was driven by funding issues and demand rather than supply. Working with Michael Kremer and others, I spent a lot of time encouraging countries to order vaccines and order early not just to save lives but to save GDP. We were advisors to the World Bank and encouraged them to offer loans but even after the World Bank offered billions in loans there was reluctance to spend big sums. There were supply shortages in 2021 in Africa, as there were elsewhere, but these quickly gave way to demand issues. Doshi et al. (2024) offer an accurate summary:

Several reasons likely account for low coverage with COVID-19 vaccines, including limited political commitment, logistical challenges, low perceived risk of COVID-19 illness, and variation in vaccine confidence and demand (3). Country immunization program capacity varies widely across the African Region. Challenges include weak public health infrastructure, limited number of trained personnel, and lack of sustainable funding to implement vaccination programs, exacerbated by competing priorities, including other disease outbreaks and endemic diseases as well as economic and political instability.

Thus, lack of domestic vaccine production wasn’t the real problem—remember, most developed countries had little or no domestic production either but they did get vaccines relatively quickly. The second flaw in the rationale for the AVMA is its pan-African framing. Africa is a continent, not a country. Why would manufacturing capacity in Senegal serve Kenya better than production in India or Belgium? There’s a peculiar assumption of pan-African solidarity, as if African countries operate with shared interests that go beyond those observed in other countries that share a continent.

Both problems with the rationale for AVMA are illustrated by South Africa’s Aspen pharmaceuticals. Aspen made a deal to manufacture the J&J vaccine in South Africa but then exported doses to Europe. After outrage ensued it was agreed that 90% of the doses would be kept in Africa but Aspen didn’t receive a single order from an African government. Not one.

Now to the more difficult issue of capacity. Africa produces less than .1% of the world’s vaccines today. The African Union has what it acknowledges is an “ambitious goal” to produce over 60 percent of the vaccines needed for Africa’s population locally by 2040. To evaluate the plausibility of this goal do note that this would require multiple Serum‑of‑India‑sized plants.

More generally, vaccines are complex products requiring big up-front investments and long lead times:

Vaccine manufacturing is one of the most demanding in industry. First, it requires setting up production facilities, and acquiring equipment, raw materials, and intellectual property rights. Then, the manufacturer will implement robust manufacturing processes and manage products portfolio during the life cycle. Therefore, manufacturers should dispose of an experienced workforce. Manufacturing a vaccine is costly and takes seven years on average. For instance, it took about 5–10 years to India, China, and Brazil to establish a fully integrated vaccine facility. A longer establishment time can be expected for African countries lacking dedicated expertise and finance. Manufacturing a vaccine can costs several dozens to hundreds of million USD in capital invested depending on the vaccine type and disease indication.

All countries in Africa rank low on the economic complexity index, a measure of whether a country can produce sophisticated and complex products (based on the diversity and complexity of their export basket). But let us suppose that domestic production is stood up. We must still ask, at what price? If domestic manufacturing ends up being more expensive than buying abroad (as GAVI acknowledges is a possibility even with GAVI’s subsidies), will African countries buy “locally” and pay more or will solidarity go out the window?

Finally, even if complex vaccines are produced at a competitive price, we still haven’t solved the demand problem. GAVI again has a rather strange acknowledgment of this issue:

Secondly, adequate country demand is another critical enabler. For AVMA to be successful, African countries will need to buy the vaccines once they appear on the Gavi menu. The Secretariat is committed to ongoing work with the AU and Member States on demand solidarity under Pillar 3 of Gavi’s Manufacturing Strategy.

So to address vaccine inequity, GAVI is investing in local production….but the need to manufacture “demand solidarity” among African governments reveals both the flaw in the premise and the weakness of the plan.

Keep in mind that the WHO only recognizes South Africa and Egypt as capable of regulating the domestic production of vaccines (and Nigeria as capable of regulating vaccine imports). In other words, most African governments do not have regulatory systems capable of evaluating vaccine imports let alone domestic production.

GAVI wants to sell the AVMA as if were an AMC (Advance Market Commitment) but it isn’t. It’s industrial policy. An AMC would offer volume‑and‑price guarantees open to any manufacturer in the world. An AMC with local production constraints is a weighted down AMC, less likely to succeed.

None of this is to imply that GAVI has no role to play. In addition to a true AMC, GAVI could arrange contracts to pay existing global suppliers to maintain idle capacity that can pivot to African‑priority antigens within 100 days. GAVI could possibly also help with regulatory convergence. There is an African Medicines Agency which aims to operate like the EMA but it has only just begun. If the AMA can be geared up, it might speed up vaccine approval through mutual recognition pacts.

The bottom line is that the $1.2 billion committed to AVMA would likely better more lives if it was directed toward GAVI’s traditional strengths in pooled procurement and distribution, mechanisms that have proven successful over the past two decades. Instead, AVMA drags GAVI into African industrial policy. A poor gamble.

BBB on drug price negotiations

The sweeping Republican policy bill that awaits President Trump’s signature on Friday includes a little-noticed victory for the drug industry.

The legislation allows more medications to be exempt from Medicare’s price negotiation program, which was created to lower the government’s drug spending. Now, manufacturers will be able to keep those prices higher.

The change will cut into the government’s savings from the negotiation program by nearly $5 billion over a decade, according to an estimate by the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office.

…the new bill spares drugs that are approved to treat multiple rare diseases. They can still be subject to price negotiations later if they are approved for larger groups of patients, though the change delays those lower prices.

This is the most significant change to the Medicare negotiation program since it was created in 2022 by Democrats in Congress.

Here is more from the NYT. Knowledge of detail is important in such matters, but one hopes this is the good news it appears to be.