Category: Education

The new Greek-language edition of Modern Principles of Economics

My Conversation with Hollis Robbins

Here is the audio and video, here is part of the CWT summary:

Now a dean at Sonoma State University, Robbins joined Tyler to discuss 19th-century life and literature and more, including why the 1840s were a turning point in US history, Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Calvinism, whether 12 Years a Slave and Django Unchained are appropriate portraits of slavery, the best argument for reparations, how prepaid postage changed America, the second best Herman Melville book, why Ayn Rand and Margaret Mitchell are ignored by English departments, growing up the daughter of a tech entrepreneur, and why teachers should be like quarterbacks.

Here is one excerpt:

COWEN: You’ve written a good deal on the history of the postal service. How did the growth of the postal service change romance in America?

ROBBINS: Well, everybody could write a letter. [laughs] In 1844 — this was the other exciting thing that happened in the 1840s. Rowland Hill in England changed the postal service by inventing the idea of prepaid postage. Anybody could buy a stamp, and then you’d put the stamp on the letter and send the letter.

Prior to that, you had to go to the post office. You had to engage with the clerk. After the 1840s and after prepaid postage, you could just get your stamps, and anybody could send a letter. In fact, Frederick Douglass loved the idea of prepaid post for the ability for the enslaved to write and send letters. After that, people wrote letters to each other, letters home, letters to their lovers, letters to —

COWEN: When should you send a sealed letter? Because it’s also drawing attention to itself, right?

ROBBINS: Well, envelopes — it’s interesting that envelopes, sealed envelopes, came about 50 years after the post office became popular, so you didn’t really have self-sealing envelopes until the end of the 19th century.

COWEN: That was technology? Or people didn’t see the need for it?

ROBBINS: Technology, the idea of folding the envelope and then having it be gummed and self-sealing. There were a number of patents, but they kept breaking down. But technology finally resolved it at the end of the 19th century.

Prior to that, you would write in code. Also, paper was expensive, so you often wrote across the page horizontally and then turned it to the side and crossed the page, writing in the other direction. If somebody was really going to snoop on your letters, they had to work for it.

COWEN: On net, what were the social effects of the postal service?

ROBBINS: Well, communication. The post office and the need for the post office is in our Constitution.

COWEN: It was egalitarian? It was winner take all? It liberated women? It helped slaves? Or what?

ROBBINS: All those things.

COWEN: All those things.

ROBBINS: But yeah, de Tocqueville mentioned this in his great book in the 1830s that anybody — some farmer in Michigan — could be as informed as somebody in New York City.

And:

COWEN: Margaret Mitchell or Ayn Rand?

ROBBINS: Well, it’s interesting that two of the best-selling novelists of the 20th-century women are both equally ignored by English departments in universities. Margaret Mitchell and Gone with the Wind is paid attention to a little bit just because, as I said, it’s something that literature and film worked against, but not Ayn Rand at all.

And:

COWEN: What’s a paradigmatic example of a movie made better by a good soundtrack?

ROBBINS: The Pink Panther — Henry Mancini’s score. The movie is ridiculous, but Henry Mancini’s score — you’re going to be humming it now the rest of the day.

And:

COWEN: What is the Straussian reading of Babar the Elephant?

ROBBINS: When’s the last time you read it?

COWEN: Not long ago.

Recommended throughout.

Watch out for the weakies!: the O-Ring model in scientific research

Team impact is predicted more by the lower-citation rather than the higher-citation team members, typically centering near the harmonic average of the individual citation indices. Consistent with this finding, teams tend to assemble among individuals with similar citation impact in all fields of science and patenting. In assessing individuals, our index, which accounts for each coauthor, is shown to have substantial advantages over existing measures. First, it more accurately predicts out-of-sample paper and patent outcomes. Second, it more accurately characterizes which scholars are elected to the National Academy of Sciences. Overall, the methodology uncovers universal regularities that inform team organization while also providing a tool for individual evaluation in the team production era.

That is part of the abstract of a new paper by Mohammad Ahmadpoor and Benjamin F. Jones.

Shruti Rajagopalan update

Next week Dr. Shruti Rajagopalan (also an Emergent Ventures winner) will be joining Mercatus as a senior research fellow, focused on Indian political economy, property rights, and economic development.

Shruti earned her PhD from George Mason in 2013 and most recently she is an associate professor of economics at Purchase College, SUNY. She is also a fellow of the Classical Liberal Institute at NYU, and will be teaching at the newly-formed Indian School of Public Policy in New Delhi.

Welcome Shruti!

You can follow Shruti on Twitter here.

Climate change sentences to ponder

But shame is the wrong emotion. “The more we try to change other people’s behavior — especially by making them feel bad — the less likely we will be to succeed,” Edward Maibach of the Center for Climate Change Communication at George Mason University told me.

That is from Seth Kugel at the NYT.

My podcast with Russ Roberts, EconTalker

Russ was the interviewer, he and I both think it is the best discussion we have had of eleven (!) interactions. Here is the link. Recommended.

My Conversation with Masha Gessen

Here is the transcript and audio, here is the summary:

Masha joined Tyler in New York City to answer his many questions about Russia: why was Soviet mathematics so good? What was it like meeting with Putin? Why are Russian friendships so intense? Are Russian women as strong as the stereotype suggests — and why do they all have the same few names? Is Russia more hostile to LGBT rights than other autocracies? Why did Garry Kasparov fail to make a dent in Russian politics? What did The Americans get right that Chernobyl missed? And what’s a good place to eat Russian food in Manhattan?

Here is excerpt:

COWEN: Why has Russia basically never been a free country?

GESSEN: Most countries have a history of never having been free countries until they become free countries.

[laughter]

COWEN: But Russia has been next to some semifree countries. It’s a European nation, right? It’s been a part of European intellectual life for many centuries, and yet, with the possible exception of parts of the ’90s, it seems it’s never come very close to being an ongoing democracy with some version of free speech. Why isn’t it like, say, Sweden?

GESSEN: [laughs] Why isn’t Russia like . . . I tend to read Russian history a little bit differently in the sense that I don’t think it’s a continuous history of unfreedom. I think that Russia was like a lot of other countries, a lot of empires, in being a tyranny up until the early 20th century. Then Russia had something that no other country has had, which is the longest totalitarian experiment in history. That’s a 20th-century phenomenon that has a very specific set of conditions.

I don’t read Russian history as this history of Russians always want a strong hand, which is a very traditional way of looking at it. I think that Russia, at breaking points when it could have developed a democracy or a semidemocracy, actually started this totalitarian experiment. And what we’re looking at now is the aftermath of the totalitarian experiment.

And:

GESSEN: …I thought Americans were absurd. They will say hello to you in the street for no reason. Yeah, I found them very unreasonably friendly.

I think that there’s a kind of grumpy and dark culture in Russia. Russians certainly have a lot of discernment in the fine shades of misery. If you ask a Russian how they are, they will not cheerfully respond by saying they’re great. If they’re miserable, they might actually share that with you in some detail.

There’s no shame in being miserable in Russia. There’s, in fact, a lot of validation. Read a Russian novel. You’ll find it all in there. We really are connoisseurs of depression.

Finally there was the segment starting with this:

COWEN: I have so many questions about Russia proper. Let me start with one. Why is it that Russians seem to purge their own friends so often? The standing joke being the Russian word for “friend” is “future enemy.” There’s a sense of loyalty cycles, where you have to reach a certain bar of being loyal or otherwise you’re purged.

Highly recommended.

Income-sharing in Africa

Several African countries have introduced state loan schemes. But governments have struggled to chase up debts. The private sector is now trying to do a better job. Kepler and Akilah, an all-female college in Kigali, are working with Chancen International, a German foundation, to try out a model of student financing popular among economists—Income Share Agreements. Chancen pays the upfront costs of a select group of students. Once they graduate, alumni pay Chancen a share of their monthly income, up to a maximum of 180% of the original loan. If they do not get a job, they pay nothing.

That is from The Economist, a survey article on higher education in Africa. Here are related links on the same scheme.

“A national experiment reveals where a growth mindset improves achievement”

I don’t believe this result, from David S. Yeager, et.al., but I put it out for your consideration, just published in Nature and receiving much attention:

A global priority for the behavioural sciences is to develop cost-effective, scalable interventions that could improve the academic outcomes of adolescents at a population level, but no such interventions have so far been evaluated in a population-generalizable sample. Here we show that a short (less than one hour), online growth mindset intervention—which teaches that intellectual abilities can be developed—improved grades among lower-achieving students and increased overall enrollment to advanced mathematics courses in a nationally representative sample of students in secondary education in the United States. Notably, the study identified school contexts that sustained the effects of the growth mindset intervention: the intervention changed grades when peer norms aligned with the messages of the intervention. Confidence in the conclusions of this study comes from independent data collection and processing, pre-registration of analyses, and corroboration of results by a blinded Bayesian analysis.

Big if true, as they say. Via many of you, thanks.

Addendum: Alex covered this as a working paper last year with more details.

Has anyone said this yet?

Consider the right-wing, conservative, and libertarian movements — is there a good word for them as a general collective? For now I’ll use “conservative,” while recognizing that the lack of generally recognized standard bearers means that “conservative” and “radical” these days blur into each other, and furthermore conservative and libertarian views have areas of real and significant conflict.

Who is today the most influential conservative intellectual with other conservative and libertarian intellectuals? (I once said Jordan Peterson is the most influential intellectuals with the general public.)

It seems obvious to me that this is Peter Thiel (admittedly I am a biased observer, for a number of reasons, one being that the Thiel Foundation is a supporter of Emergent Ventures). Quite simply, if Peter gives a talk with new material in it, it gets discussed more than if anyone else does.

What else might his qualifications be for “most influential conservative intellectual”?

He has had a major hand in the tech revolution, and with his later view that technology is stagnating more generally.

He is the talent spotter par excellence, having had a hand in the rise of Mark Zuckerberg, Elon Musk, Reid Hoffman, Eric Weinstein, and others.

A major hand in Trump/populism/nationalism, or whatever it should be called. I should note that Peter is often highly influential with those who disagree with him about Trump.

Spoke/wrote/co-authored a bestselling book — Zero to One — which also was a huge hit in China. And the samizdat lecture notes, from Peter’s Stanford talks, were a big hit in advance of the book.

A major hand in the critique of political correctness, and the spread of that critique.

He foresaw that globalization might contract rather than keep on expanding. The final answer isn’t in yet on this one, but so far Peter is looking prescient.

A major hand in causing people to rethink higher education, through his Thiel Fellows program.

A major hand in stimulating the interest of others in Girard and Strauss, and maybe someday Christianity?

This point has nothing to do with how much you agree with Peter or not. It simply occurred to me that no one had said this before, or have they?

By the way, here is David Perell on Peter Thiel on Christianity.

Identity Politics Versus Independent Thinking

Anthony Kronman, former Dean of the Yale Law school, writes in the WSJ:

The politically motivated and group-based form of diversity that dominates campus life today discourages students from breaking away, in thought or action, from the groups to which they belong. It invites them to think of themselves as representatives first and free agents second. And it makes heroes of those who put their individual interests aside for the sake of a larger cause. That is admirable in politics. It is antithetical to one of the signal goods of higher education.

…Grievance is the stuff of political life…Academic disagreements are different. Important ones are often inflamed by passion too. But the goal of those involved is to persuade their adversaries with better facts and arguments—not to bludgeon them into submission with complaints of abuse, injustice and disrespect to increase their share of power. Today, the spirit of grievance has been imported into the academy, where it undermines the common search for truth by permeating it with a sense of hurt and wrong on the part of minority students, and guilt on the part of those who are blamed for their suffering.

…For college students, the search for truth is important not because reaching it is guaranteed—there are no such guarantees—but as a discipline of character. It instills habits of self-criticism, modesty and objectivity. It strengthens their ability to subject their own opinions and feelings to higher and more durable measures of worth. It increases their self-reliance and their respect for the values and ideas of those far removed in time and circumstance. In all these ways, the search for truth promotes the habit of independent-mindedness that is a vital antidote to what Tocqueville called the “tyranny of majority opinion.”

…Tocqueville was an enthusiastic admirer of America’s democracy. He thought it the most just system of government the world had ever known. But he was also sensitive to its pathologies. Among these he identified the instinct to believe what others do in order to avoid the labor and risk of thinking for oneself. He worried that such conformism would itself become a breeding ground for despots.

As a partial antidote, Tocqueville stressed the importance of preserving, within the larger democratic order, islands of culture devoted to the undemocratic values of excellence and truth. These could be, he thought, enclaves for protecting the independence of mind that a democracy like ours especially needs.

Today our colleges and universities are doing a poor job of meeting this need, and the idea of diversity is at least partly to blame. It has become the basis of an illiberal and antirational academic cult—one that undermines the spirit of self-reliance and the commitment to truth on which not only higher education, but the whole of our democracy, depends.

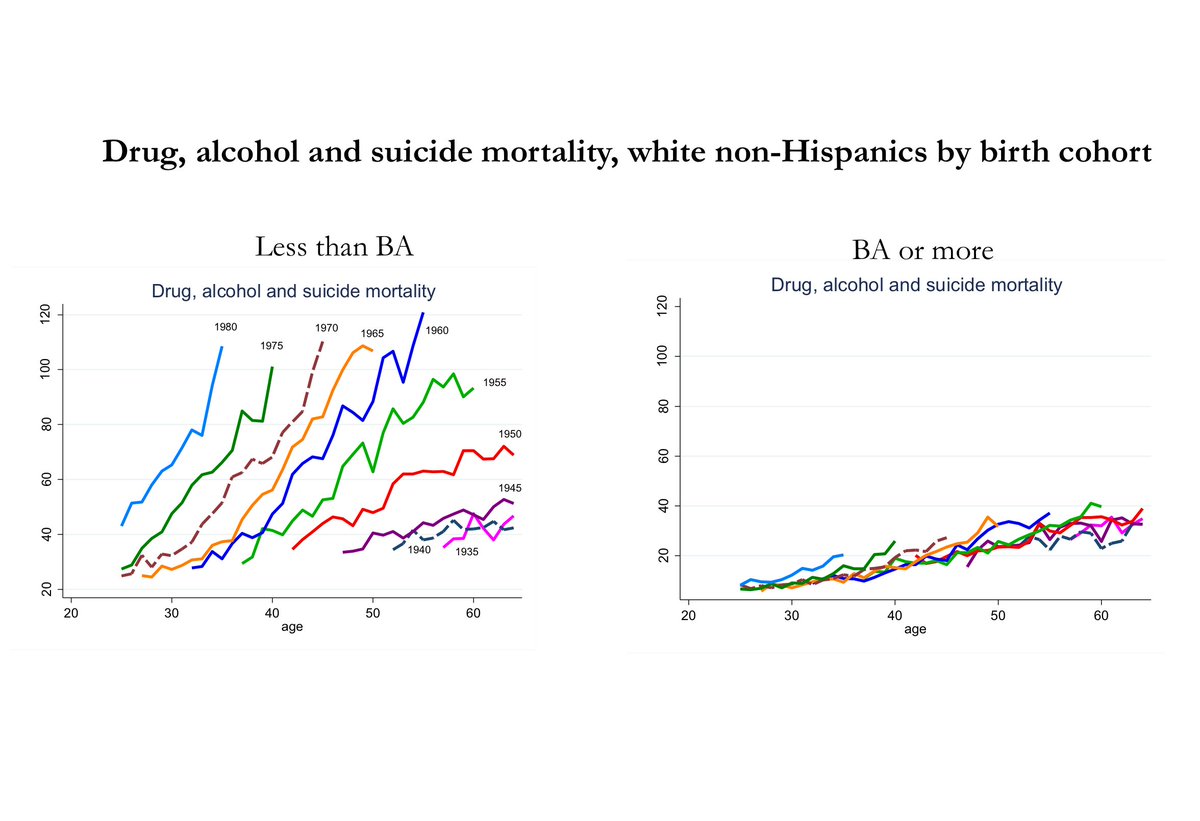

Mortality Change Among Less Educated Americans

The bottom of the educational distribution is doing very very poorly:

Changing mortality rates among less educated Americans are difficult to interpret because the least educated groups (e.g. dropouts) become smaller and more negatively selected over time. New partial identification methods let us calculate mortality changes at constant education percentiles from 1992–2015. We find that middle-age mortality increases among non-Hispanic whites are driven almost entirely by changes in the bottom 10% of the education distribution. Drivers of mortality change differ substantially across groups. Deaths of despair explain a large share of mortality change among young non-Hispanic whites, but a small share among older whites and almost none among non-Hispanic blacks.

That is from Paul Novosad and Charlie Rafkin.

A Toolkit of Policies to Promote Innovation

That is the new Journal of Economic Perspectives article by Nicholas Bloom, John Van Reenen, and Heidi Williams. Most of all, such articles should be more frequent and receive greater attention and higher status, as Progress Studies would suggest. Here is one excerpt:

…moonshots may be justified on the basis of political economy considerations. To generate significant extra resources for research, a politically sustainable vision needs to be created. For example, Gruber and Johnson (2019) argue that increasing federal funding of research as a share of GDP by half a percent—from 0.7 percent today to 1.2 percent, still lower than the almost 2 percent share observed in 1964 in Figure 1—would create a $100 billion fund that could jump-start new technology hubs in some of the more educated but less prosperous American cities (such as Rochester, New York, and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania). They argue that such a fund could generate local spillovers and, by alleviating spatial inequality, be more politically sustainable than having research funds primarily flow to areas with highly concentrated research, such as Palo Alto, California, and Cambridge, Massachusetts.

In general I agree with their points, but would have liked to have seen more on freedom to build, and of course on culture, culture, culture. At the very least, policy is endogenous to culture, and culture shapes many economic outcomes more directly as well. I’m fine with tax credits for R&D, but I just don’t see them as in the driver’s seat.

America, in two charts, social average is over

Forgive the formatting, and yes the axes are not square up (in fact it should look worse), here is the link. And here is the source with explanation, p.48.

Paul Krugman’s Most Evil Idea

Erik Torenberg, co-founder of the VC firm Village Global, interviews me in a wide-ranging podcast. Here is one bit from a series of questions on what do you disagree about with ____. In this case, Paul Krugman.

AT: …Krugman and I are almost in perfect agreement. Only marginally different. Paul says ‘Republicans are corrupt, incompetent, unprincipled and dangerous to a civil society’. I agree with that entirely. I would only change one word. I would change the word Republicans to the word politicians. If Paul could only be convinced of doing that, coming over to the libertarian side, we would be in complete agreement. But he is much more partisan than I am and even though I worry about Republicans more than Democrats at this particular point in time I think the larger incentive is that we all need to be worried about politicians rather than any one particular party.

Although I agree with Paul a lot of the time, sometimes he does just drive me absolutely batty. He just says things which I think are so wrong. In his latest column which to be fair was written as a column fifty years in the future so maybe it was a bit tongue in cheek. The column was pretending that Elon Musk and Peter Thiel were a hundred years of age and fit and fiddle and still major players in society. And Krugman wrote:

Life extension for a privileged few is by its nature a socially destructive technology and the time has come to ban it.

Now to me this is just evil. This is like something out of Ayn Rand’s Anthem, that it is evil to live longer than your brothers and all must be sentenced to death so that none live more than their allotted time. I think it is evil if we accept even the premise of his argument that these technologies are very expensive. Even on that ground it’s evil to kill people just so that they don’t live longer than average. But perhaps even a bigger point is that I think these technologies of life extension are some of the most important things that people are working on today. And the billionaires are doing an incredible service to humanity by investing in these radical ideas and pushing the frontier and that is going to have spillover effects on everyone. If we are to reach the singularity it will because the billionaires are getting us there earlier and faster and they are the ones pushing us to the singularity and everyone will benefit from these life extension technologies.

So I agree with Paul quite a bit, more than you might expect, but sometimes he just says things which are absolutely evil.

We cover open borders, whether capitalism and democracy are compatible, the Baumol effect and more. Listen to the whole thing.