Category: Education

Sentences to ponder

Graduate students experience depression and anxiety at six times the rate of the general population, Gumport mentioned.

A study produced by Paul Barreira, director of Harvard’s University Health Service, found that “the prevalence of depression and anxiety symptoms among economics Ph.D. students is comparable to the prevalence found in incarcerated populations.”

Most of the article (the top segment) is an interesting consideration of the economics of Stanford University Press.

Gender and the confidence gap

That is the topic of my latest Bloomberg column, here is one bit:

The first new study focuses on performance in high school, and the startling result is this: Girls with more exposure to high-achieving boys (as proxied by parental education) have a smaller chance of receiving a bachelor’s degree. Furthermore, they do worse in math and science, are less likely to join the labor force, and more likely to have more children, which in turn may limit their later career prospects.

Those are disturbing results. Exposure to high-achieving peers is normally expected to be a plus, not a minus. It is what parents are trying to do when they place their children into better schools, or when school systems work hard to attract better students.

And:

A second new study finds that even blind review does not avoid gender bias in the processing of grant proposal applications, drawn from data from the Gates Foundation. It turns out that women and men have different communications styles, with the women more likely to use narrow words, and the men more likely to use broader ones. And reviewers, it turns out, favor broad words, which are more commonly associated with more sweeping claims, and disfavor the use of too many narrow words.

The net result is that “even in an anonymous review process, there is a robust negative relationship between female applicants and the scores assigned by reviewers.” This discrepancy persists even after controlling for subject matter and other variables. Notably, however, it disappears when controlling for different rhetorical styles.

These two studies probably are connected to each other. While the two sets of researchers do not address each other’s claims, it is not a huge leap to think of broader, more sweeping language as reflecting a kind of confidence, whether merited or not. Narrow words, on the other hand, may reflect a lower level of confidence or a greater sense of rhetorical modesty. Not only might lower confidence hurt many women in life, but a greater unwillingness to signal confidence — regardless of whether it’s genuine — might hurt them too.

There is much more at the link, recommended.

My Conversation with Margaret Atwood

She requires no introduction, this conversation involved a bit of slapstick, so unlike many of the others it is better heard than read. Here is the audio and transcript. Here is the opening:

COWEN: Just to start with some basic questions about Canada, which you’ve written on for decades — what defines the Canadian sense of humor?

MARGARET ATWOOD: Wow. [laughs] What defines the Canadian sense of humor? I think it’s a bit Scottish.

COWEN: How so?

ATWOOD: Well, it’s kind of ironic. It depends on what part of Canada you’re in. I think the further west you go, the less of a sense of humor they have.

[laughter]

ATWOOD: But that’s just my own personal opinion. My family’s from Nova Scotia, so that’s as far east as you can get. And they go in for deadpan lying.

[laughter]

COWEN: In 1974, you wrote, “The Canadian sense of humor was often obsessed with the issue of being provincial versus being cosmopolitan.”

ATWOOD: Yeah.

COWEN: You think that’s still true?

ATWOOD: Depends again. You know, Canada’s really big. In fact, there’s a song called “Canada’s Really Big.” You can find it on the internet. It’s by a group called the Arrogant Worms. That kind of sums up Canada right there for you.

The burden of the song is that all of these other countries have got all of these other things, but what Canada has is, it’s really big. It is, in fact, very big. Therefore, it’s very hard to say what is particularly Canadian. It’s a bit like the US. Which part of the US is the US? What is the most US thing —

COWEN: Maybe it’s Knoxville, Tennessee, right now. Right? The Southeast.

ATWOOD: You think?

COWEN: But it used to be Cleveland, Ohio.

ATWOOD: Did it?

COWEN: Center of manufacturing.

ATWOOD: When was that? [laughs] When was that?

COWEN: If you look at where the baseball teams are, you see what the US —

And from her:

ATWOOD: Yeah, so what is the most Canadian thing about Canada? The most Canadian thing about Canada is that when they ran a contest that went “Finish this sentence. As American as apple pie. As Canadian as blank,” the winning answer was “As Canadian as plausible under the circumstances.”

And a question from me:

COWEN: But you’ve spoken out in favor of the cultural exception being part of the NAFTA treaty that protects Canadian cultural industries. Is it strange to think that having more than half the [Toronto] population being foreign born is not a threat to Canadian culture, but that being able to buy a copy of the New York Times in Canada is a threat?

In addition to Canada, we talk about the Bible, Shakespeare, ghosts, her work habits, Afghanistan, academia, Peter the Great, writing for the future, H.G. Wells, her heretical feminism, and much much more.

Our three new hires at George Mason economics

Northwestern Ph.D, Brown post doc, Joel Mokyr student. Here is her job market paper:

Job Market Paper

The Political Economy of Famine: the Ukrainian Famine of 1933 Download Job Market Paper (pdf)

Abstract: The famine of 1932–1933 in Ukraine killed as many as 2.6 million people out of a population of approximately 30 million. Three main explanations have been offered: negative weather shock, poor economic policies, and genocide. This paper uses variation in exposure to poor government policies and in ethnic composition within Ukraine to study the impact of policies on mortality, and the relationship between ethnic composition and mortality. It documents that (1) the data do not support the negative weather shock explanation: 1931 and 1932 weather predicts harvest roughly equal to the 1925 — 1929 average; (2) bad government policies (collectivization and the lack of favored industries) significantly increased mortality; (3) collectivization increased mortality due to drop in production on collective farms and not due to overextraction from collectives (although the evidence is indirect); (4) back-of-the-envelope calculations show that collectivization explains at least 31\% of excess deaths; (5) ethnic Ukrainians seem more likely to die, even after controlling for exposure to poor Soviet economic policies; (6) Ukrainians were more exposed to policies that later led to mortality (collectivization and the lack of favored industries); (7) enforcement of government policies did not vary with ethnic composition (e.g., there is no evidence that collectivization was enforced more harshly on Ukrainians). These results provide several important takeaways. Most importantly, the evidence is consistent with both sides of the debate (economic policies vs genocide). (1) backs those arguing that the famine was man-made. (2) — (4) support those who argue that mortality was due to bad policy. (5) is consistent with those who argue that ethnic Ukrainians were targeted. For (6) and (7) to support genocide, it has to be the case that Stalin had the foresight that his policies would fail and lead to famine mortality years after they were introduced (and therefore disproportionately exposed Ukrainians to them).

Cultural economics and economic history, St. Gallen Ph.D, Harvard post doc, co-author with Joe Henrich.

Job market paper, “Catholic Church, Kin Networks, and Institutional Development“:

Political institutions vary widely around the world, yet the origin of this variation is not well understood. This study tests the hypothesis that the Catholic Church’s medieval marriage policies dissolved extended kin networks and thereby fostered inclusive institutions. In a difference-in-difference setting, I demonstrate that exposure to the Church predicts the formation of inclusive, self-governed commune cities before the year 1500CE. Moreover, within medieval Christian Europe, stricter regional and temporal cousin marriage prohibitions are likewise positively associated with communes. Strengthening this finding, I show that longer Church exposure predicts lower cousin marriage rates; in turn, lower cousin marriage rates predict higher civicness and more inclusive institutions today. These associations hold at the regional, ethnicity and country level. Twentieth-century cousin marriage rates explain more than 50 percent of variation in democracy across countries today.

Harvard Ph.D, assistant professor of economics at University of Toronto, he works in the new field genonomics and has co-authored with David Cesarini. Here is his presentation on GWAS of risk tolerance:

Here is his paper (with co-authors) “Genome-wide association analyses of risk tolerance and risky behaviors in over one million individuals identify hundreds of loci and shared genetic influences.”

I am very much looking forward to their arrival, they all seem like great colleagues, and I am honored to have played a role on the recruiting committee.

What should I ask Russ Roberts?

I will be doing a Conversations with Tyler with Russ, the master podcaster himself, but of course also a prolific author in multiple fields. So what should I ask him? Here is Russ on Wikipedia, here is Russ’s home page.

My Conversation with Ed Boyden, MIT neuroscientist

Here is the transcript and audio, highly recommended, and for background here is Ed’s Wikipedia page. Here is one relevant bit for context:

COWEN: You’ve trained in chemistry, physics, electrical engineering, and neuroscience, correct?

BOYDEN: Yeah, I started college at 14, and I focused on chemistry for two years, and then I transferred to MIT, where then I switched into physics and electrical engineering, and that’s when I worked on quantum computing.

COWEN: Five areas, actually. Maybe more.

BOYDEN: Guess so.

COWEN: Should more people do that? Not the median student, but more people?

BOYDEN: It’s a good question.

And:

COWEN: Are we less creative if all the parts of our mind become allies? Maybe I’m afraid this will happen to me, that I have rebellious parts of my mind, and they force me to do more interesting things, or they introduce randomness or variety into my life.

BOYDEN: This is a question that I think is going to become more and more urgent as neurotechnology advances. Already there are questions about attention-focusing drugs like Ritalin or Adderall. Maybe they make people more focused, but are you sacrificing some of the wandering and creativity that might exist in the brain and be very important for not only personal productivity but the future of humanity?

I think what we’re realizing is that when you intervene with the brain, even with brain stimulation, you can cause unpredictable side effects. For example, there’s a part of the brain called the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. That’s actually an FDA-approved site for stimulation with noninvasive magnetic pulses to treat depression. But patients, when they’re stimulated here . . . People have done studies. It can also change things like trust. It can change things like driving ability.

There’s only so many brain regions, but there’s millions of things we do. Of course, intervening with one region might change many things.

And:

COWEN: What kind of students are you likely to hire that your peers would not hire?

BOYDEN: Well, I really try to get to know people at a deep level over a long period of time, and then to see how their unique background and interests might change the field for the better.

I have people in my group who are professional neurosurgeons, and then, as I mentioned, I have college dropouts, and I have people who . . . We recently published a paper where we ran the brain expansion process in reverse. So take the baby diaper polymer, add water to expand it, and then you can basically laser-print stuff inside of it, and then collapse it down, and you get a piece of nanotechnology.

The co–first author of that paper doesn’t have a scientific laboratory background. He was a professional photographer before he joined my group. But we started talking, and it turns out, if you’re a professional photographer, you know a lot of very practical chemistry. It turns out that our big demo — and why the paper got so much attention — was we made metal nanowires, and the way we did it was using a chemistry not unlike what you do in photography, which is a silver chemistry.

And this:

COWEN: Let’s say you had $10 billion or $20 billion a year, and you would control your own agency, and you were starting all over again, but current institutions stay in place. What would you do with it? How would you structure your grants? You’re in charge. You’re the board. You do it.

Finally:

COWEN: If you’re designing architecture for science, what do you do? What do you change? What would you improve? Because presumably most of it is not designed for science. Maybe none of it is.

BOYDEN: I’ve been thinking about this a lot, actually, lately. There are different philosophies, like “We should have open offices so everybody can see and talk to each other.” Or “That’s wrong. You should have closed spaces so people can think and have quiet time.” What I think is actually quite interesting is this concept that maybe neither is the right approach. You might want to think about having sort of an ecosystem of environments.

My group — we’re partly over at the Media Lab, which has a lot of very open environments, and our other part of the group is in a classical sort of neuroscience laboratory with offices and small rooms where we park microscopes and stuff like that. I actually get a lot of productivity out of switching environments in a deliberate way.

There is much more of interest at the link.

Genes, income, and happiness

Significant differences between genetic correlations indicated that, the genetic variants associated with income are related to better mental health than those linked to educational attainment (another commonly-used marker of SEP). Finally, we were able to predict 2.5% of income differences using genetic data alone in an independent sample. These results are important for understanding the observed socioeconomic inequalities in Great Britain today.

That is from a new paper by W. David Hill, et.al. And from Abdel Abdellouai’s summary:

Educational attainment shows a larger genetic overlap with subjective wellbeing than IQ does (rgs = .11 & .03, respectively), while income shows a larger genetic overlap with subjective wellbeing than both education or IQ (rg = .32).

All via Richard Harper.

Using Nature to Understand Nurture

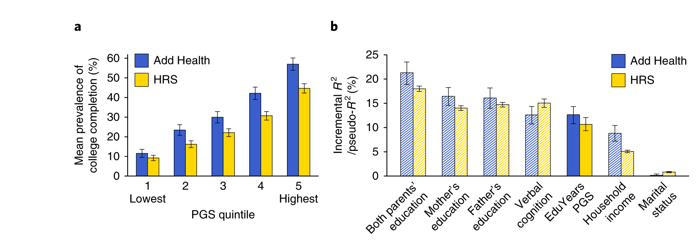

An excellent new working paper uses genetic markers for educational attainment to track students through the  high school math curriculum to better understand the role of nature, nurture and their interaction in math attainment. The paper begins with an earlier genome wide association study (GWAS) of 1.1 million people that found that a polygenic score could be used to (modestly) predict college completion rates. Panel (a) in the figure at right shows how college completion is five times higher in individuals with an education polygenic score (ed-PGS) in the highest quintile compared to individuals with scores in the lowest quintile; panel b shows that ed-PGS is at least as good as household income at predicting college attainment but not quite as good as knowing the educational level of the parents.

high school math curriculum to better understand the role of nature, nurture and their interaction in math attainment. The paper begins with an earlier genome wide association study (GWAS) of 1.1 million people that found that a polygenic score could be used to (modestly) predict college completion rates. Panel (a) in the figure at right shows how college completion is five times higher in individuals with an education polygenic score (ed-PGS) in the highest quintile compared to individuals with scores in the lowest quintile; panel b shows that ed-PGS is at least as good as household income at predicting college attainment but not quite as good as knowing the educational level of the parents.

Of the million plus individuals with ed-PGS, some 3,635 came from European-heritage individuals who were entering US high school students in 1994-1995 (the Add Health sample). Harden, Domingue et al. take the ed-PGS of these individuals and match them up with data from their high school curricula and their student transcripts.

What they find is math attainment is a combination of nature and nurture. First, students with higher ed-PGS are more likely to be tracked into advanced math classes beginning in grade 9. (Higher ed-PGS scores are also associated with higher socio-economic status families and schools but these differences persist even after controlling for family and school SES or looking only at variation within schools.) Higher ed-PGS also predicts math persistence in the following years. The following diagram tracks high ed-PGS (blue) with lower ed-PGS (brown) over high school curricula/years and post high-school. Note that by grade 9 there is substantial tracking and some cross-over but mostly (it appears to me) in high-PGS students who fall off-track (note in particular the big drop off of blue students from Pre-Calculus to None in Grade 12).

Nature, however, is modified by nurture. “Students had higher returns to their genetic propensities for educational attainment in higher-status schools.” Higher ed-PGS students in lower SES schools were less likely to be tracked into higher-math classes and lower-SES students were less likely to persist in such classes.

It would be a mistake, however, to conclude that higher-SES schools are uniformly better without understanding the tradoffs. Lower SES schools have fewer high-ability students which makes it difficult to run advanced math classes. Perhaps the lesson here is that bigger schools are better, particularly bigger schools in poorer SES districts. A big school in a low SES district can still afford an advanced math curriculum.

The authors also suggest that more students could take advanced math classes. Even among the top 2% of students as measured by ed-PGS only 31% took Calculus in the high-SES schools and only 24% in the low SES schools.It’s not clear to me, however, that high-PGS necessitates high math achievement. Notice that many high-PGS students take pre-calc in Grade 11 but then no math in Grade 12 but they still go on to college and masters degrees. Lots of highly educated people are not highly-educated in math. Still it wouldn’t be a surprise if there were more math talent in the pool.

There is plenty to criticize in the paper. The measure of SES status by school (average mother’s educational attainment) leaves something to be desired. Moreover, there are indirect genetic effects, which the authors understand and discuss but don’t have the data to test. An indirect genetic effect occurs when a gene shared by parent and child has no direct effect on educational capacity (i.e. it’s not a gene for say neuronal development) but has an indirect “effect” because it is correlated with something that parent’s with that gene do to modify the environment of their children. Nevertheless, genes do have direct effects and this paper forces us to acknowledge that behavioral genetics has implications for policy.

Should every student be genotyped and tracked? On the one hand, that sounds horrible. On the other hand, it would identify more students of high ability, especially from low SES backgrounds. Genetics tells us something about a student’s potential and shouldn’t we try to maximize potential?

For homework, work out the equilibrium for inequality, rewatch the criminally underrated GATTACA and for an even more horrifying picture of the future, pay careful attention to the Mirrlees model of optimal income taxation.

Has the time for income-sharing arrived?

That is the topic of my new Bloomberg column, here is one excerpt:

To be sure, there are problems with the idea of equitizing human capital. For instance, what if less talented, less hard-working individuals turn out to be the most likely to sign away part of their future income? That creates a problem that economists call “adverse selection.” This is a real issue, but it hasn’t stopped companies from selling equity and startups from selling venture capital shares. As for the students, due diligence and talent measurement may suffice to identify enough good students with bright prospects.

There are also genuine questions about how far this model can be extended. The demand for labor is robust in information technology, but would a similar system work for philosophy professors or prospective musicians? In both cases incomes are undoubtedly lower, motivations non-pecuniary, and the chances for real success more remote. The company Pando Pooling, meanwhile, is trying equitization with minor league baseball players. The importance of raw baseball talent may be so paramount, however, that companies cannot much improve the labor market prospects of their clients.

Note also that we already equitize each other’s labor in many non-explicit, non-corporate ways. If two economists write a paper together, for example, each is tying his or her fate somewhat to the other. And if two people in business decide to share networks or trade favors, each has a stake in the success of the other.

The piece also consider Lambda School in San Francisco as an institution trying to operationalize this practice.

The friendship paradox and systematic biases in perceptions and social norms

Except I call it the Twitter paradox, and it is about how neurotics really get on each others’ nerves:

The “friendship paradox” (first noted by Feld in 1991) refers to the fact that, on average, people have strictly fewer friends than their friends have. I show that this oversampling of more popular people can lead people to perceive more engagement than exists in the overall population. This feeds back to amplify engagement in behaviors that involve complementarities. Also, people with the greatest proclivity for a behavior choose to interact the most, leading to further feedback and amplification. These results are consistent with studies finding overestimation of peer consumption of alcohol, cigarettes, and drugs and with resulting high levels of drug and alcohol consumption.

Toffee

Toffee is the world’s first dating app for people who were privately educated…[W]hether it’s a shared interest in horse racing or rugby, Toffee users can indicate which sporting and social events they are interested in or likely to attend, to further enhance the matching logic.

Here are the visuals on the web site. For the pointer I thank the excellent Kevin Lewis.

The internet, vs. “culture”

The internet gives us the technological capability to transmit digital information seamlessly over any distance. The concept of culture is more complicated, but I mean the influences and inspirations we grow up with, such as the family norms and practices of a place, the street scenes, the local architecture and cuisine, and the slang. Culture comes from both nearby and more distant sources, but the emotional vividness of face-to-face interactions means that a big part of culture is intrinsically local.

Rapid Amazon delivery, or coffee shops that look alike all around the world, stem in part from the internet. The recommendations from the smart person who works in the local bookstore, or the local Sicilian recipe that cannot be reproduced elsewhere, are examples of culture.

Since the late 1990s, the internet has become far more potent. Yet the core techniques of culture have hardly become more productive at all, unless we are talking about through the internet. The particular aspects of culture which have done well are those easily translated to the digital world, such as songs on YouTube and streaming. When people are staring at their mobile devices for so many minutes or hours a day, that has to displace something. Those who rely on face-to-face relationships to transmit their influence and authority don’t have nearly the clout they once did.

The internet gaining on culture has made the last twenty years some of the most revolutionary in history, at least in terms of the ongoing fight for mindshare, even though the physical productivity of our economy has been mediocre. People are upset by the onset of populism in world politics, but the miracle is that so much stability has reigned, relative to the scope of the underlying intellectual and what you might call “methodological” disruptions.

The traditional French intellectual class, while retrograde in siding largely with culture, understands the ongoing clash fairly well. Consistently with their core loyalties, they do not mind if the influence of the internet is stifled or even destroyed, or if the large American tech companies are collateral damage.

Many Silicon Valley CEOs are in the opposite boat. Most of their formative experiences are with the internet and typically from young ages. The cultural perspective of the French intellectuals is alien to them, and so they repeatedly do not understand why their products are not more politically popular. They find it easier to see that the actual users love both their products and their companies. Of course, for the intellectuals and culture mandarins that popularity makes the entire revolution even harder to stomach.

Donald Trump ascended to the presidency because he mastered both worlds, namely he commands idiomatic American cultural expressions and attitudes, and also he has been brilliant in his political uses of Twitter. AOC has mastered social media only, and it remains to be seen whether Kamala Harris and Joe Biden have mastered either, but probably not.

Elizabeth Warren is now leading a campaign to split up the major tech companies, but unlike the Europeans she is not putting forward culture as an intellectual alternative. Her anti-tech campaign is better understood as an offset of some of the more hostility-producing properties of the internet itself. It is no accident that the big tech companies take such a regular pounding on social media, which is well-designed to communicate negative sentiment. In this regard, the American and European anti-tech movements are not nearly as close as they might at first seem.

In the internet vs. culture debate, the internet is at some decided disadvantages. For instance, despite its losses of mindshare, culture still holds many of the traditional measures of status. Many intellectuals thus are afraid to voice the view that a lot of culture is a waste of time and we might be better off with more time spent on the internet. Furthermore, many of the responses to the tech critics focus on narrower questions of economics or the law, without realizing that what is at stake are two different visions of how human beings should think and indeed live. When that is the case, policymakers will tend to resort to their own value judgments, rather than listening to experts. For better or worse, the internet-loving generations do not yet hold most positions of political power (recall Zuckerberg’s testimony to Congress).

The internet also is good at spreading glorified but inaccurate pictures of the virtues of local culture, such as when Trump tweets about making America great again, or when nationalist populism becomes an internet-based, globalized phenomenon.

The paradox is that only those with a deep background in culture have the true capacity to defend the internet and also to understand its critics, but they are exactly the people least likely to take up that battle.

Determinants of college majors

Students who happen to be assigned classes in one of four required subjects during the semester when they’re supposed to pick a major are twice as likely to major in the assigned subject, according to a new working paper from Pope, and Richard Patterson and Aaron Feudo of the U.S. Military Academy.

This held true regardless of how well a student did or how much they liked the course, according to the economists’ analysis of U.S. Military Academy class data from 2001 to 2015. Their database included grades, class times and students’ opinions of the course. It allowed them to control for factors such as students’ hometowns and racial backgrounds.

“Small and seemingly unimportant things can really have a large impact on people’s life decisions,” Pope said. Often students cite a specific class or teacher as justification for this life-altering choice.

In a related paper, the economists, along with Carnegie Mellon’s Kareem Haggag, showed students are about 10 percent less likely to major in a subject if they took a class at 7:30 a.m. Likewise, as students grow more fatigued during the day they grow about 10 percent less likely to major in the subject covered by each successive class…

Given how easily a first choice of major can be swayed by accidents of timing and environment, it’s perhaps not surprising that 37 percent of students eventually switch, according to a new paper from University of Memphis economists Carmen Astorne-Figari and Jamin D. Speer that will be published in the journal Economics of Education Review…

Students with lower GPAs are more likely to leave their major. But so are women of all ability levels. In contrast, men are more likely to drop out instead of sticking around and trying a different subject, according to a study published last year by Astorne-Figari and Speer.

Both men and women are most likely to abandon majors in the sciences. In addition, education and philosophy appear in the top five majors men leave most frequently, while women are more likely to leave computer science…

Students tend to switch to less competitive majors.

And:

On net, business, social sciences and economics tend to gain the most students from major switching, while biology, computer science and medicine (medical and health services) tend to lose the most.

What is wrong with social justice warriors?

Curious if you’ve read this (has a PDF link):

http://libjournal.uncg.edu/ijcp/article/view/249Is this paper bad? If it is bad, what is bad about it? How would you describe “what is bad about it” in a way that would connect to a college freshman who finds his/her economics and critical race theory classes to be equally interesting and deserving of further study? This extends to broader questions about “what precisely is undesirable about the state of social-justice-oriented academic study?” I have seen a lot of backhanded stuff from you on this topic, but not a centrally articulated, earnest answer.

That is from my email, and I would broaden the question to be about social justice warriors more generally. Most of all, I would say I am all for social justice warriors! Properly construed, that is. But two points must be made:

1. Many of the people who are called social justice warriors I would not put in charge of a candy shop, much less trust them to lead the next jihad.

2. Many social justice warriors seem more concerned with tearing down, blacklisting, and deplatforming others, or even just whining about them, rather than working hard to actually boost social justice, whatever you might take that to mean. Most of that struggle requires building things in a positive way, I am sorry to say.

That all said, do not waste too much of your own energies countering the not-so-helpful class of social justice warriors. It is not worth it. Perhaps someone needs to play such a role, but surely those neuterers are not, or at least should not be, the most talented amongst us.

No matter what your exact view of the world, or what kind of ornery pessimist or determinist or conservative or even reactionary you may be, you should want to be working toward some kind of emancipation in the world. No, I am not saying there always is a clear “emancipatory” side of a debate, or that most issues are “us vs. them.” Rather, if you are not sure you are doing the right thing, ask a simple question: am I building something? Whether it be a structure, an institution, or simply a positive idea, proposal, or method.

The answer to that building question may not always be obvious, but it stands a pretty good chance of getting you to an even better question for your next round of inquiry.

The 2019 Public Choice Outreach Conference

It’s time to get your applications in for the 2019 Public Choice Outreach conference, a crash course in public choice for students from all fields and walks of life! Professors, please encourage your students to apply!

When is the Public Choice Outreach Conference?

The 2019 Outreach Conference will be held June 14-16th at the Hyatt Centric Arlington in Rosslyn, VA.

What is the Public Choice Outreach Conference?

The Public Choice Outreach Conference is a compact lecture series designed as a “crash course” in Public Choice for students planning careers in academia, journalism, law, or public policy. Graduate students and advanced undergraduates are eligible to apply. Many past participants of the Outreach seminar have gone on to notable careers in academia, law and business.

What will I learn?

Students are introduced to the history and basic tools of public choice analysis, such as models of voting and elections, and models of government and legislative organization. Students also learn to apply public choice theory to a wide range of relevant issues. Finally, students will be introduced to “constitutional economics” and the economics of rule making.

This is a chance to hear talks from Robin Hanson, Alex Tabarrok, Shruti Rajagopolan, Tyler Cowen and more.

Who can apply?

Graduate students and advanced undergraduates are eligible to apply. Students majoring in economics, history, international studies, law, philosophy political science, psychology, public administration, religious studies, and sociology have attended past conferences. Advanced degree students with a demonstrated interest in political economy or demonstrated interest in political economy are invited to apply. Applicants unfamiliar with Public Choice and students from outside of George Mason University are especially encouraged.

What are the fees involved?

Outreach has no conference fee – it is free to attend. Room and meals are included for all participants. However, ALL travel costs are the responsibility of the participants.

Click here for the 2019 Outreach Application