Are tariffs a regressive tax?

I hear all the time that they are, but is that true?:

There are two sides to this. First, we need to figure out how consumption differs by income. Here it’s pretty clear that lower-income people consume more goods which are traded, and the goods which they consume have a lower elasticity of substitution (Fajgelbaum and Khandelwal, 2016). Put concretely, this is because the poor consume fewer luxuries which can’t be exchanged for other goods. In practice, the distributional effects in the United States are particularly large, because even within relatively narrow categories of goods lower quality goods face higher tax rates. (Acosta and Cox (2025) attribute this to a peculiarity of trade negotiations. The within category rates were shaped by negotiations in the 1930s, after which we no longer negotiated individual items but instead shifted all items within a category by a fixed percentage).

However, we need to take into account the effect of who gets more jobs. If it reallocates production to low-skill industries primarily employing the poor, then it may redistribute from top to bottom. Borusyak and Jaravel (2023) compare the two, and show that almost all of the redistribution is occurring within income deciles. Tariffs are costly to the consumer, and are indeed disproportionately costly to lower income consumers, but it does so by reallocating jobs to primarily lower income workers. Taking into account both effects, the distributional consequences of tariffs and trade are approximately nil.

Here is more from Nicholas Decker. These are the kinds of results that easily could be overturned by subsequent research (see the further remarks at the link), nonetheless at this time we probably should not be pushing regressive tariffs as established science or a firm conclusion. I’ll say it again: the best (and very good) argument against the tariffs is simply that they set the government on the trail of a previously dormant revenue source. That rarely ends well, though it is hard for non-libertarians to pick up this argument and run with it.

Will this law be enforced?

Mayor Adams has proposed a new 15mph speed limit for all ebikes in New York City. Lyft received direction from the Mayor’s office to reduce the maximum pedal assist speed of Citi Bike ebikes from 18mph to 15mph in anticipation of the rule taking effect. Our technical team worked hard to respond to this directive and the change is in effect across our ebike fleet as of June 20, 2025.

Although the pedal assist speed on Citi Bikes has been adjusted, here’s what hasn’t changed: You’ll still get that smooth, electric boost that makes tackling hills and longer distances a breeze. Our ebikes will continue to provide the same reliable and fun way to get around the city. Since Citi Bike first launched ebikes, riders have taken over 85 million ebike rides, traveling more than 190 million miles. In other words, you all have circled the globe 7,700 times on ebikes.

Here is the link. I am personally happy with a libertarian approach to ebikes, namely let people take their chances and limit the ability to sue the cars that bump into you. Nonetheless I am amazed that a world with a Consumer Product Safety Commission, and an FDA, allows small, unprotected vehicles to travel on our roads, more or less unhindered. All the more so for motorcycles. Paris has banned e-scooters, though not ebikes. o3 recommends a 20 mph speed limit (write in your vote for mayor!).

Here are some complaints on Reddit about the new lower speed limit. What I in fact observe is that, at least in NYC, there are few penalties for running red lights with your bicycle or ebike.

Sentences to ponder

In a much more narrow case, a big study of the views of AI and machine learning researchers revealed high levels of trust in international organizations and low levels of trust in national militaries.

That is from Matt Yglesias.

Friday assorted links

1. Did the Spanish Inquisition hurt science?

2. Mexico fertility rate below that of the U.S., and Mexico City is below one.

3. Are volcanoes a risk to solar-dominated grids?

5. ChatGPT agent.

6. The return of the elderly pop star.

7. “Until 1970, the UK was the world’s top producer of nuclear energy.”

D’accord !

That is from the French embassy in the UK.

Lookism and VC

Do subtle visual cues influence high-stakes economic decisions? Using venture capital as a laboratory, this paper shows that facial similarity between investors and entrepreneurs predicts positive funding decisions but negative investment outcomes. Analyzing early-stage deals from 2010-2020, we find that greater facial resemblance increases match probability by 3.2 percentage points even after controlling for same race, gender, and age, yet funded companies with similar-looking investor-founder pairs have 7 percent lower exit rates. However, when deal sourcing is externally curated, facial similarity effects disappear while demographic homophily persists, indicating facial resemblance primarily operates as an initial screening heuristic. These findings reveal a novel form of homophily that systematically shapes capital allocation, suggesting that interventions targeting deal sourcing may eliminate the negative influence of visual cues on investment decisions.

That is from a recent paper by Emmanuel Yimfor, via the excellent Kevin Lewis.

Naveen Nvn’s ideological migration (from my email)

I started following American politics only in 2010/2011, which is two years after his [Buckley’s] death, and I was in India at that time.

Plus, I was very liberal at that time.

Around 2018-19ish, I was pushed into a centrist stance because I was appalled by wokeness, especially on campuses. I was in graduate school in the US at that time. Although I didn’t experience wokeness advocacy in the classroom except two or three incidents, I saw signs of wokeness on campus a lot. But even then, I was quite libertarian on how universities ought to handle campus politics.

I picked up God and Man at Yale around this time because wokeness was my primary concern.

I’ve always known that conservatives love that book. I assumed it would be a defense of free inquiry and against universities having a preferred ideology.

However, to my surprise, in the book, he argued explicitly that Yale was neglecting its true mission and it should uphold its “foundational values,” as he put it. I assumed he would be promoting a libertarian outlook on campus politics, but he was arguing the opposite.

He said Yale and other elite universities should incorporate free markets and traditional perspectives directly into the curriculum because they are betraying a contract that the current alumni and the administration have with the founders of the universities. It was a pretty shocking advocacy of conservatism being imposed on the students, and I didn’t like that at all.

But later on, around 2020-ish, I became a conservative (thanks to you; more on that in the link below). But even as late as early 2023, I still held a libertarian view on academic freedom and campus politics.

(You may be interested in a comment I left on your ‘Why Young People Are Socialist’ post yesterday, in which I shared how I was once a liberal, then turned centrist, and how I finally turned conservative. You are a major influence.)

But after Oct 7, all of that changed quite fast. Watching the pro-Hamas protests on campuses that started the very next day after October 7, before even one IDF soldier set foot on Gaza, I immediately thought about God and Man at Yale. I wanted to go back and re-read God and Man at Yale.

Everything I’ve witnessed after Oct 7 — Harvard defending Claudine Gay, Harvard explicitly stating they’re an “international institution” and not an American institution, DEI, anti-White, anti-Asian discrimination, etc. has convinced me that WFB Jr. was right.

Elite universities ought to be promoting free markets and pro-American, pro-Western views. I don’t believe we should have a completely libertarian approach to academic freedom. That’s untenable in this day and age. (Again, demographics is destiny, even within organizations.)

I’ve become significantly less libertarian on a wide range of issues compared to where I was just two years ago, and not just on academic freedom/university direction.

So yes, WFB Jr. has influenced me on this idea.

David Brooks on the AI race

When it comes to confidence, some nations have it and some don’t. Some nations once had it but then lost it. Last week on his blog, “Marginal Revolution,” Alex Tabarrok, a George Mason economist, asked us to compare America’s behavior during Cold War I (against the Soviet Union) with America’s behavior during Cold War II (against China). I look at that difference and I see a stark contrast — between a nation back in the 1950s that possessed an assumed self-confidence versus a nation today that is even more powerful but has had its easy self-confidence stripped away.

There is much more at the NYT link.

The political culture/holiday culture that is French

The French government proposed cutting two public holidays per year to boost economic growth as part of a budget plan that it billed as a “moment of truth” to avoid a financial crisis. But in a country where vacations are sacred, the idea — unsurprisingly — prompted outrage across the political spectrum, suggesting it may have little chance of becoming law.

Here is more from Annabelle Timsit at the Washington Post. How many countries will, over the next ten years, in fact prove governable?

Thursday assorted links

1. Claude for financial services.

2. Golf ball diver nets 100k a year (short video).

3. Zvi on Kimi.

4. China fact of the day: “China’s commercial airlines are limited to using 20% of its airspace, giving rise to an average route curvature of 17% compared to 5% in the US and Europe.”

5. Are these the new dresses for conservative women?

6. “This is probably the last time in human history that an AI is outperformed by a real human coder.”

The Sputnik vs. Deep Seek Moment: The Answers

In The Sputnik vs. DeepSeek Moment I pointed out that the US response to Sputnik was fierce competition. Following Sputnik, we increased funding for education, especially math, science and foreign languages, organizations like ARPA were spun up, federal funding for R&D was increased, immigration rules were loosened, foreign talent was attracted and tariff barriers continued to fall. In contrast, the response to what I called the “DeepSeek” moment has been nearly the opposite. Why did Sputnik spark investment while DeepSeek sparks retrenchment? I examine four explanations from the comments and argue that the rise of zero-sum thinking best fits the data.

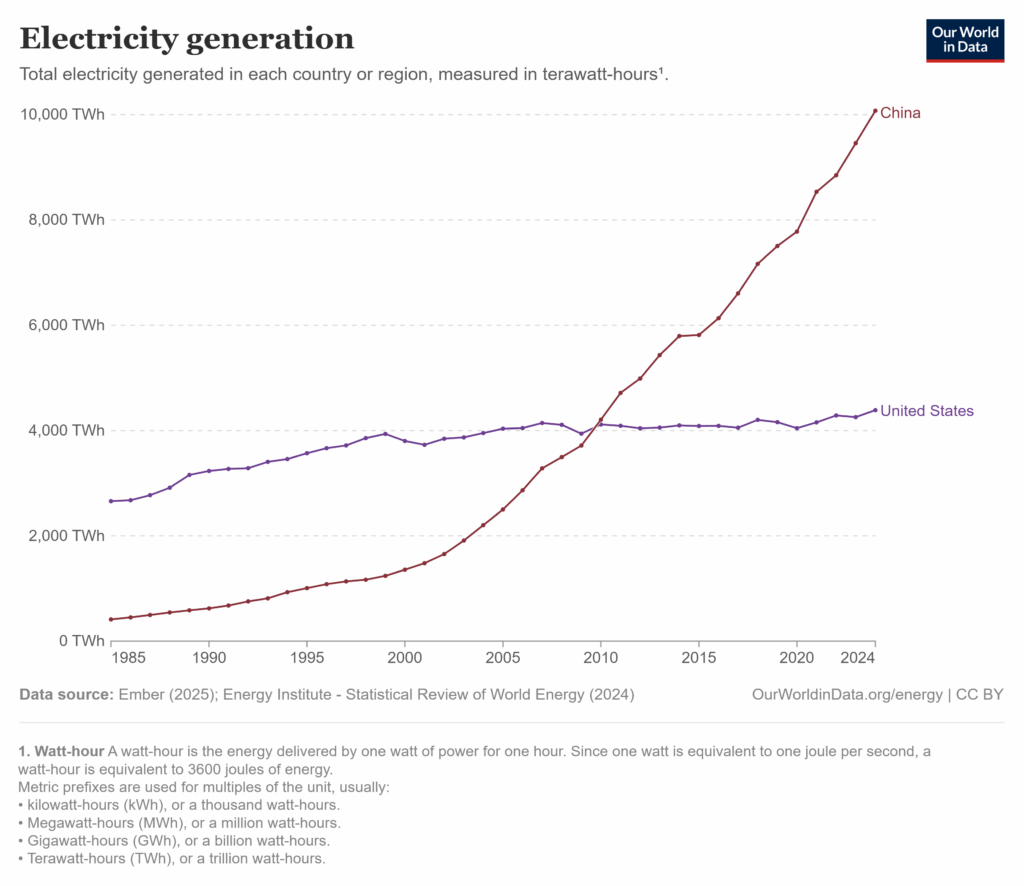

Several comments fixated on DeepSeek itself, dismissing it as neither impressive nor threatening. Perhaps but DeepSeek was merely a symbol for China’s broader rise: the world’s largest exporter, manufacturer, electricity producer, and military by headcount. These critiques missed the point.

Some commenters argued that Sputnik provoked a strong response because it was seen as an existential threat, while DeepSeek—and by extension China—is not. I certainly hope China’s rise isn’t existential, and I’m encouraged that China lacks the Soviet Union’s revolutionary zeal. As I’ve said, a richer China offers benefits to the United States.

But many influential voices do view China as a very serious, even existential, threat—and unlike the USSR, China is economically formidable.

More to the point, perceived existential stakes don’t answer my question. If the threat were greater, would we suddenly liberalize immigration, expand trade, and fund universities? Unlikely. A more plausible scenario is that if the threat were greater, we would restrict harder—more tariffs, less immigration, more internal conflict.

Several commenters, including my colleague Garett Jones, pointed to demographics—especially voter demographics. The median age has risen from 30 in 1950 to 39 in recent years; today’s older, wealthier, more diverse electorate may be more risk-averse and inward-looking. There’s something to this, but it’s not sufficient. Changes in the X variables haven’t been enough to explain the change in response given constant Betas so demography doesn’t push that far but does it even push in the right direction?

Age might correlate with risk-aversion, for example, but the Trump coalition isn’t risk-averse—it’s angry and disruptive, pushing through bold and often rash policy changes.

A related explanation is that the U.S. state has far less fiscal and political slack today than it did in 1957. As I argued in Launching, we’ve become a warfare–welfare state—possibly at the expense of being an innovation state. Fiscal constraints are real, but the deeper issue is changing preferences. It’s not that we want to return to the moon and can’t—it’s that we’ve stopped wanting to go.

In my view, the best explanation for the starkly different responses to the Sputnik and DeepSeek moments is the rise of zero-sum thinking—the belief that one group’s gain must come at another’s expense. Chinoy, Nunn, Sequiera and Stantcheva show that the zero sum mindset has grown markedly in the U.S. and maps directly onto key policy attitudes.

Zero sum thinking fuels support for trade protection: if other countries gain, we must be losing. It drives opposition to immigration: if immigrants benefit, natives must suffer. And it even helps explain hostility toward universities and the desire to cut science funding. For the zero-sum thinker, there’s no such thing as a public good or even a shared national interest—only “us” versus “them.” In this framework, funding top universities isn’t investing in cancer research; it’s enriching elites at everyone else’s expense. Any claim to broader benefit is seen as a smokescreen for redistributing status, power, and money to “them.”

Zero-sum thinking doesn’t just explain the response to China; it’s also amplified by the China threat. (hence in direct opposition to some of the above theories, the people who most push the idea that the China threat is existential are the ones who are most pushing the zero sum response). Davidai and Tepper summarize:

People often exhibit zero-sum beliefs when they feel threatened, such as when they think that their (or their group’s) resources are at risk…Similarly, working under assertive leaders (versus approachable and likeable leaders) causally increases domain-specific zero-sum beliefs about success….. General zero-sum beliefs are more prevalent among people who see social interactions as a competition and among people who possess personality traits associated with high threat susceptibility, such as low agreeableness and high psychopathy, narcissism and Machiavellianism.

Zero-sum thinking can also explain the anger we see in the United States:

At the intrapersonal level, greater endorsement of general zero-sum beliefs is associated with more negative (and less positive) affect, more greed and lower life satisfaction. In addition, people with general zero-sum beliefs tend to be overly cynical, see society as unjust, distrust their fellow citizens and societal institutions, espouse more populist attitudes, and disengage from potentially beneficial interactions.

…Together, these findings suggest a clear association between both types of zero-sum belief and well-being.

Focusing on zero-sum thinking gives us a different perspective on some of the demographic issues. In the United States, for example, the young are more zero-sum thinkers than the old and immigrants tend to be less zero-sum thinkers than natives. The likeliest reason: those who’ve experienced growth understand that everyone can get a larger slice from a growing pie while those who have experienced stagnation conclude that it’s us or them.

The looming danger is thus the zero-sum trap: the more people believe that wealth, status, and well-being are zero-sum, the more they back policies that make the world zero-sum. Restricting trade, blocking immigration, and slashing science funding don’t grow the pie. Zero-sum thinking leads to zero-sum policies, which produce zero-sum outcomes—making the zero sum worldview a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Someday I want to see the regressions

Each infant born from the procedure carries DNA from a man and two women. It involves transferring the nucleus from the fertilised egg of a woman carrying harmful mitochondrial mutations into a donated egg from which the nucleus has been removed.

For some carriers this is the only option because conventional IVF does not produce enough healthy embryos to use after pre-implantation diagnosis.

The researchers consistently reject the popular term “three-parent babies”, said Turnbull, “but it doesn’t make a scrap of difference.”

Here is more from Clive Cookson at the FT. From Newcastle. And here is some BBC coverage.

Markets in everything those new service sector jobs

Witchcraft and spellwork have become an online cottage industry. Faced with economic uncertainty and vapid dating apps, some people are putting their beliefs—and disposable income—into love spells, career charms and spirit cleansers.

Etsy, an online marketplace for crafts and vintage, has long been home to psychics and mystics, but the platform has enjoyed new callouts from TikTokers as a destination for witchcraft.

The concept of hiring an Etsy witch hit a fever pitch when influencer Jaz Smith told her TikTok followers that she had paid one to make sure the weather was perfect during her Memorial Day Weekend wedding. The blue skies and warm temperature have inspired TikTok audiences to find Etsy witches of their own. Smith didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Rohit Thawani, a creative director in Los Angeles, said Smith was his inspiration for paying an Etsy witch $8.48 to cast a spell on the New York Knicks ahead of Game 5 of the Eastern Conference finals in May.

Thawani found a witch offering discount codes. Thawani was half-kidding about the transaction but was amazed when the Knicks won. “Maybe there’s something more cosmic out there,” Thawani, 43, said.

Thawani bought a second spell ($21.18) from the Etsy witch for Game 6, but the Knicks lost. He doesn’t rule out the possibility that Indiana Pacers fans “used their devil magic,” he joked.

Magic practitioners sell on Instagram, Shopify and TikTok, but most customers say Etsy is their go-to.

The shop MariahSpells has over 4,000 sales on Etsy and 4.9 stars and sells a permanent protection spell for about $200. Another shop, Spells by Carlton, has over 44,000 sales and lists a “bring your ex lover back” spell for about $7.

Here is more from the WSJ, via the excellent Samir Varma.

Wednesday assorted links

1. Can LLMs help with child abuse investigations?

2. A foundation model to predict and capture human cognition?

3. Simone and Malcolm Collins are surrounding their children with AI.

4. Michael Truell and Patrick Collison talk.

5. Roughly 1,500 tarantulas found stuffed in boxes meant for chocolate cake.

Asymmetric economic power?

America’s trading partners have largely failed to retaliate against Donald Trump’s sweeping tariffs, allowing a president taunted for “always chickening out” to raise nearly $50bn in extra customs revenues at little cost.

Four months since Trump fired the opening salvo of his trade war, only China and Canada have dared to hit back at Washington imposing a minimum 10 per cent global tariff, 50 per cent levies on steel and aluminium, and 25 per cent on autos.

At the same time US revenues from customs duties hit a record high of $64bn in the second quarter — $47bn more than over the same period last year, according to data published by the US Treasury on Friday.

China’s retaliatory tariffs on American imports, the most sustained and significant of any country, have not had the same effect, with overall income from custom duties only 1.9 per cent higher in May 2025 than the year before.

Here is more from the FT. To be clear, I do not think this is good. Nonetheless it amazes me how many economists a) reject the “Leviathan” approach to analyzing public choice and U.S. government, b) think “normative nationalism” is fine, c) have expressed partial “trade skepticism” for some while, and d) think our government should raise a lot more revenue, including through consumption taxes…and yet they find this to be about the worst policy they ever have seen.

Some also will tell you that higher inflation is not such a terrible thing, though whether they extend this view to inflation from real shocks is disputable.

With some debatable number of national security exceptions, zero tariffs is the way to go. But you can only get there through broadly libertarian frameworks, not through conventional “mid-establishment” policy analyses.