My excellent Conversation with David Robertson

David is one of my very favorite conductors of classical music, especially in contemporary works but not only. He also is super-articulate and has the right stage presence to make for a great podcast guest. Here is the audio, video, and transcript. Here is part of the episode summary:

Tyler and David explore Pierre Boulez’s centenary and the emotional depths beneath his reputation for severity, whether Boulez is better understood as a surrealist or a serialist composer, the influence of non-Western music like gamelan on Boulez’s compositions, the challenge of memorizing contemporary scores, whether Boulez’s music still sounds contemporary after decades, where skeptics should start with Boulez, how conductors connect with players during a performance, the management lessons of conducting, which orchestra sections posed Robertson the greatest challenges, how he and other conductors achieve clarity of sound, what conductors should read beyond music books, what Robertson enjoys in popular music, how national audiences differ from others, how Robertson first discovered classical music, why he insists on conducting the 1911 version of Stravinsky’s Petrushka rather than the 1947 revision, and more.

Here is one excerpt:

COWEN: I have some general questions about conducting. How is it you make your players feel better?

ROBERTSON: Oh, I think the music actually does that.

COWEN: But you smile at them, you occasionally wink or just encourage them, or what is it you do?

…ROBERTSON: There’s an unwritten rule in an orchestra that you don’t turn around and look at somebody, even if they’ve played something great. I think that part of our job is to show the rest of the players, gee, how great that was. Part of the flexibility comes from if, let’s say, the oboe player has the reed from God tonight, that if they want to stay on the high note a little bit longer, or the soprano at the Metropolitan Opera, that you just say, “Yes, let’s do this. This is one of these magical moments of humanity, and we are lucky to be a part of it.”

COWEN: When do the players look at you?

ROBERTSON: Oh, that’s a fabulous question. I’ll now have to go public with this. The funny thing is, every single individual in an orchestra looks up at a different time. It’s totally personal. There are some people who look up a whole bar before, and then they put their eyes down, and they don’t want any more eye contact. There are other people who look as though they’re not looking up, but you can see that they’re paying attention to you before they go back into their own world. And there are people who look up right before they’re going to play.

One of the challenges for a conductor is, as quickly as possible with a group you don’t know, to try and actually memorize when everybody looks up because I always say, this is like the paper boy or the paper girl. If you’re on your route, and you have your papers in your bicycle satchel, and you throw it at the window, and the window is closed, you’ll probably have to pay for the pane of glass.

Whereas if the window goes up, which is the equivalency of someone looking up to get information, that’s the moment where you can send the information through with your hands or your face or your gestures, that you’re saying, “Maybe try it this way.” They pick that information up and then use it.

But the thing that no one will tell you, and that the players themselves don’t often realize, is that instinctively, and I think subconsciously, almost every player looks up after they’ve finished playing something. I think it’s tojust check in to see, “Am I in the right place?”

Recommended.

Robert Aliber, RIP

The renowned international economist, here is an obituary. Here is his Wikipedia page.

What should I ask Anne Appelbaum?

Yes, I will be doing a Conversation with her. From Wikipedia:

Anne Elizabeth Applebaum…is an American journalist and historian. She has written about the history of Communism and the development of civil society in Central and Eastern Europe. She became a Polish citizen in 2013.

Applebaum has worked at The Economist and The Spectator magazines, and she was a member of the editorial board of The Washington Post (2002–2006). She won the Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction in 2004 for Gulag: A History. She is a staff writer for The Atlantic magazine, as well as a senior fellow of the Agora Institute and the School of Advanced International Studies at Johns Hopkins University .

But she has done more yet, including work on a Polish cuisine cookbook. So what should I ask her?

Wednesday assorted links

GAVI’s Ill-Advised Venture Into African Industrial Policy

GAVI, the Vaccine Alliance has saved millions of lives by delivering vaccines to the world’s poorest children at remarkably low cost. It’s frankly grotesque that RFK Jr. cites “safety” as a reason to cut funding—when the result of such cuts will be more children dying from preventable diseases. Own it.

You can find plenty of RFK Jr. criticism elsewhere, however, and GAVI is not above criticism. Thus, precisely because GAVI’s mission is important, I want to focus on a GAVI project that I think is ill-motivated and ill-advised, GAVI’s African Vaccine Manufacturing Accelerator (AVMA).

The motivation behind the AVMA is to “accelerate the expansion of commercially viable vaccine manufacturing in Africa” to overcome “vaccine inequity” as illustrated during the COVID crisis. The problem with this motivation is that most of Africa’s delay in receiving COVID vaccines was driven by funding issues and demand rather than supply. Working with Michael Kremer and others, I spent a lot of time encouraging countries to order vaccines and order early not just to save lives but to save GDP. We were advisors to the World Bank and encouraged them to offer loans but even after the World Bank offered billions in loans there was reluctance to spend big sums. There were supply shortages in 2021 in Africa, as there were elsewhere, but these quickly gave way to demand issues. Doshi et al. (2024) offer an accurate summary:

Several reasons likely account for low coverage with COVID-19 vaccines, including limited political commitment, logistical challenges, low perceived risk of COVID-19 illness, and variation in vaccine confidence and demand (3). Country immunization program capacity varies widely across the African Region. Challenges include weak public health infrastructure, limited number of trained personnel, and lack of sustainable funding to implement vaccination programs, exacerbated by competing priorities, including other disease outbreaks and endemic diseases as well as economic and political instability.

Thus, lack of domestic vaccine production wasn’t the real problem—remember, most developed countries had little or no domestic production either but they did get vaccines relatively quickly. The second flaw in the rationale for the AVMA is its pan-African framing. Africa is a continent, not a country. Why would manufacturing capacity in Senegal serve Kenya better than production in India or Belgium? There’s a peculiar assumption of pan-African solidarity, as if African countries operate with shared interests that go beyond those observed in other countries that share a continent.

Both problems with the rationale for AVMA are illustrated by South Africa’s Aspen pharmaceuticals. Aspen made a deal to manufacture the J&J vaccine in South Africa but then exported doses to Europe. After outrage ensued it was agreed that 90% of the doses would be kept in Africa but Aspen didn’t receive a single order from an African government. Not one.

Now to the more difficult issue of capacity. Africa produces less than .1% of the world’s vaccines today. The African Union has what it acknowledges is an “ambitious goal” to produce over 60 percent of the vaccines needed for Africa’s population locally by 2040. To evaluate the plausibility of this goal do note that this would require multiple Serum‑of‑India‑sized plants.

More generally, vaccines are complex products requiring big up-front investments and long lead times:

Vaccine manufacturing is one of the most demanding in industry. First, it requires setting up production facilities, and acquiring equipment, raw materials, and intellectual property rights. Then, the manufacturer will implement robust manufacturing processes and manage products portfolio during the life cycle. Therefore, manufacturers should dispose of an experienced workforce. Manufacturing a vaccine is costly and takes seven years on average. For instance, it took about 5–10 years to India, China, and Brazil to establish a fully integrated vaccine facility. A longer establishment time can be expected for African countries lacking dedicated expertise and finance. Manufacturing a vaccine can costs several dozens to hundreds of million USD in capital invested depending on the vaccine type and disease indication.

All countries in Africa rank low on the economic complexity index, a measure of whether a country can produce sophisticated and complex products (based on the diversity and complexity of their export basket). But let us suppose that domestic production is stood up. We must still ask, at what price? If domestic manufacturing ends up being more expensive than buying abroad (as GAVI acknowledges is a possibility even with GAVI’s subsidies), will African countries buy “locally” and pay more or will solidarity go out the window?

Finally, even if complex vaccines are produced at a competitive price, we still haven’t solved the demand problem. GAVI again has a rather strange acknowledgment of this issue:

Secondly, adequate country demand is another critical enabler. For AVMA to be successful, African countries will need to buy the vaccines once they appear on the Gavi menu. The Secretariat is committed to ongoing work with the AU and Member States on demand solidarity under Pillar 3 of Gavi’s Manufacturing Strategy.

So to address vaccine inequity, GAVI is investing in local production….but the need to manufacture “demand solidarity” among African governments reveals both the flaw in the premise and the weakness of the plan.

Keep in mind that the WHO only recognizes South Africa and Egypt as capable of regulating the domestic production of vaccines (and Nigeria as capable of regulating vaccine imports). In other words, most African governments do not have regulatory systems capable of evaluating vaccine imports let alone domestic production.

GAVI wants to sell the AVMA as if were an AMC (Advance Market Commitment) but it isn’t. It’s industrial policy. An AMC would offer volume‑and‑price guarantees open to any manufacturer in the world. An AMC with local production constraints is a weighted down AMC, less likely to succeed.

None of this is to imply that GAVI has no role to play. In addition to a true AMC, GAVI could arrange contracts to pay existing global suppliers to maintain idle capacity that can pivot to African‑priority antigens within 100 days. GAVI could possibly also help with regulatory convergence. There is an African Medicines Agency which aims to operate like the EMA but it has only just begun. If the AMA can be geared up, it might speed up vaccine approval through mutual recognition pacts.

The bottom line is that the $1.2 billion committed to AVMA would likely better more lives if it was directed toward GAVI’s traditional strengths in pooled procurement and distribution, mechanisms that have proven successful over the past two decades. Instead, AVMA drags GAVI into African industrial policy. A poor gamble.

Markets, Culture, and Cooperation in 1850-1920 U.S.

From a very recent working paper draft by Max Posch and Itzchak Tzachi Raz:

We study how rising market integration shaped cooperative culture and behavior in the 1850–1920 United States. Leveraging plausibly exogenous changes in county-level market access driven by rail-road expansion and population growth, we show that increased market access fostered universalism, tolerance, and generalized trust—traits supporting cooperation with strangers—and shifted coopera-tion away from kin-based ties toward more generalized forms. Individual-level analyses of migrantsreveal rapid cultural adaptation after moving to more market-integrated places, especially among those exposed to commerce. These effects are unlikely to be explained by changes in population diversity,economic development, access to information, or legal institutions.

Here is the link.

Canada facts of the day

Given Canada’s vast size and low population density, I was surprised to discover that the country feels more urban than the US, with far more skyscrapers per capita. In 2024, Vancouver had 128 high rises under construction, #3 in North America. (Toronto was #1 and NYC was #2.) Even smaller Canadian cities have more tall buildings under construction than similar size US cities.

Here is more from Scott Sumner, a general essay on his trip to Canada. And analytically:

In terms of living standards, I’d guess that the bottom half of the Canadian population does as well as the bottom half of the US population (and perhaps even better if you include social indicators like drugs and crime and life expectancy.) The impression I got is that the top half of the US population is considerably richer than the top half of the Canadian population. Even so, I’d estimate that the US is perhaps 10% or at most 20% richer than Canada, not the 35.6% richer suggested by the IMF data.

Why is Canada poorer? I’m not sure. The US does have the advantage of economies of scale. But in Western Europe, smaller countries don’t seem poorer than bigger countries. Perhaps Canada is poorer because its economy is structurally similar to the European economic model. On the other hand, some of America’s richest regions (such as California and New York) have a fairly high level of taxes and regulation. So I’m puzzled.

Even the Maritimes (based on limited travel) do not seem that poor to me. Maybe it is that the American “upper upper middle class” is much richer in great numbers?

Two other points. First, higher levels of immigration into Canada can lower the per capita average, even if you think those immigrants will end up doing well.

Second, very often (too often?) we judge income flows by looking at the housing stock. And indeed the Canadian housing stock is fine (in quality, I agree they have too much NIMBY). But if we are going to judge flows by stocks, let us also look at the stock of Canadian corporations and global brands. And that is decidedly weaker. If we consider all stocks, and not just the housing stock, perhaps our picture of Canada slides closer to equilibrium once again.

Tuesday assorted links

1. Hangzhou and AI (NYT).

2. The evolution of the American civilian-military relationship.

3. Matt Levine on arbitrage in India (Bloomberg). And more from the FT. And from FT Alphaville.

4. Haiti’s great Hotel Oloffson has been destroyed by gang warfare (NYT).

5. John Arnold on how BBB treats professional bettors.

6. New federal grants for universities with right-leaning programs?

7. “We review existing research and conclude that period-based explanations focused on short-term changes in income or prices cannot explain the widespread decline [in fertility]. Instead, the evidence points to a broad reordering of adult priorities with parenthood occupying a diminished role.” Link here.

The Paradox of India

Tyler often talks about cracking cultural codes. India is the hardest—and therefore the most fascinating—cultural code I’ve encountered. The superb post The Paradox of India by Samir Varma helps to unlock some of these codes. Varma is good at describing:

In 2004, something extraordinary happened that perfectly captured India’s unique nature: A Roman Catholic woman (Sonia Gandhi) voluntarily gave up the Prime Ministership to a Sikh (Manmohan Singh) in a ceremony presided over by a Muslim President (A.P.J. Abdul Kalam) in a Hindu-majority country.

And nobody commented on it.

Think about that. In how many countries could this happen without it being THE story? In India, the headlines focused on economic policy and coalition politics. The religious identities of the key players were barely mentioned because, well, what would be the point? This is how India works.

This wasn’t tolerance—it was something deeper. It was the lived experience of a civilization where your accountant might be Jain, your doctor Parsi, your mechanic Muslim, your teacher Christian, and your vegetable vendor Hindu. Where festival holidays meant everyone got days off for Diwali, Eid, Christmas, Guru Nanak Jayanti, and Good Friday. Where secularism isn’t the absence of religion but the presence of all religions.

But goes beyond that:

You might be thinking: “This is fascinating, but I’m not Indian. I can’t draw on 5,000 years of civilizational memory. How does any of this help me navigate my increasingly polarized world?”

Here’s what I’ve learned from watching India work its magic: The mental moves that make pluralism possible aren’t mystical—they’re learnable. Think of them as cognitive tools:

The And/And Instead of Either/Or: When faced with contradictions, resist the Western urge to resolve them. Can something be both sacred and commercial? Both ancient and modern? Both yours and mine? Indians instinctively answer yes.

Contextual Truth Over Universal Law: What’s right for a Jain isn’t right for a Bengali, and that’s okay. Truth can be plural without being relative. Multiple valid perspectives can coexist without canceling each other out.

Strategic Ambiguity as Wisdom: Not everything needs to be defined, categorized, and resolved. Sometimes the wisest response is a head waggle that means yes, no, and maybe all at once.

Code-Switching as a Life Skill: Indians don’t just switch languages—they switch entire worldviews depending on context. At work, modern. At home, traditional. With friends, fusion. This isn’t hypocrisy; it’s sophisticated social navigation.

The lesson isn’t “be more tolerant.” It’s “develop comfort with unresolved multiplicity.” In a world demanding you pick sides, the Indian model suggests a radical alternative: Don’t.

In our age of rising nationalism and cultural purism, when countries are building walls and communities are retreating into echo chambers, India stands as a glorious, maddening, inspiring mess—proof that diversity isn’t just manageable but might be the secret to civilizational immortality.

After all, it’s hard to kill something that contains multitudes. When one part struggles, another thrives. When one tradition calcifies, another innovates. When one community turns inward, another builds bridges.

It’s not a bug. It’s a feature.

And maybe, just maybe, it’s exactly what the world needs to remember right now.

Read the whole thing. Part 1 of 3.

Labour considers fast-tracking approval of big projects

There are a few modest signs of progress in the UK (and Canada):

Ministers are exploring using the powers of parliament to cut the time it takes to approve new railways, power stations and other infrastructure projects.

In an attempt to promote growth, the government is examining whether it could pass legislation that would allow transport, energy and new town housing projects to circumvent swathes of the planning process.

The move could limit the ability of opponents to challenge projects in the courts and reduce scrutiny of some developments. It is loosely modelled on a Canadian scheme that was the brainchild of Mark Carney, the new prime minister and a former governor of the Bank of England.

The One Canadian Economy Act was passed by Canada’s parliament in June and gives Carney’s government powers to fast-track national projects. The Treasury is understood to be examining how a UK version could speed up the approval process for nationally significant infrastructure projects, such as offshore wind farms or even a third runway at Heathrow.

Here is more from The Times.

I write on the BBB for The Free Press

I view the Big Beautiful Bill of Trump as one of the most radical experiments in fiscal policy in my lifetime.

In essence, Trump has decided to push all of his chips to the center of the table and bet on the American economy. I would not have proposed this bill, as critics are correct to note that it increases the estimated U.S. debt by $3 to $4 trillion over the next 10 years. That is a massive boost in leverage at a time when America’s fiscal position already appeared unsustainable.

Nonetheless it is worth trying to steelman the Trump decision, and understand when it might pay off. The biggest deficit buster in the bill is the extension—and indeed boost to cuts—in corporate income tax rates. That means more resources for corporations, and stronger incentives to invest. The question is what the American economy can expect to get from that.

Since 1980, returns on resources invested in American corporations have averaged in the 9 to 11 percent range. There is no guarantee such returns will hold in the future, or that they will hold for the extra investment induced by the corporate tax cuts (e.g., maybe companies will just stash the new profits in Treasury bills). Still, an optimist might believe we can get a high rate of return on that money, thereby making America much wealthier and also more fiscally stable.

A second possible ace in the hole is pending improvements in artificial intelligence and their potential economic impact. It is already the case that U.S. productivity has risen over the last few years, and perhaps it will go up some more. That could make our new debt burden more easily affordable.

My view of the fiscal authority—Congress—is that its primary fiduciary duty is to act responsibly. The Big Beautiful Bill is not that. Nonetheless, I am reminded of the classic scene in the 1971 movie Dirty Harry when Clint Eastwood (Harry) asks, “Do I feel lucky?” Here’s to hoping.

Here is the link, there are numerous other interesting contributions, including from Furman, Summers, Scanlon, Salaam and others.

Tom Tugendhat on British economic stagnation

Second, and even more detrimental to younger generations, is a set of policies that have artificially created a highly damaging cult of housing. For many decades, too few houses have been built in the UK. Thanks in part to the tax system, housing has been transformed from a place to live and raise a family into a de facto tax free retirement fund that excludes the young. More than 56 per cent of the UK’s total housing wealth is owned by those over 60, while home ownership among those under 35 has collapsed to just 6 per cent. This has had profound social and economic consequences as fewer people marry and have children, further impairing long-term demographic regeneration. The result? More than 80 per cent of the growth in real per capita wealth over the past 30 years has come from appreciation of real estate, not from the financial investment that powers the economy.

Michael Tory, co-founder of Ondra Partners, has argued that this capital misallocation has created a self-reinforcing cycle, weakening our national and economic security. Without productive capital, we are wholly dependent on foreign investment and imported labour, straining housing supply and public services. These distortions can only be corrected through a rebalancing of our national capital allocation that puts long-term national interest above narrow electoral calculation. That means levelling the investment playing field to reduce the taxes on those whose long-term savings and investments in Britain’s future actually employ people and generate growth. Along with building more houses and stricter migration controls, this would bring home ownership into reach for younger generations.

British pension funds should invest more in British businesses as well. Here is more from the FT.

Monday assorted links

2. Okie-dokie (NYT).

3. A while back Coleman Hughes took me to play a speed chess hustler in Washington Square Park. Here is that game on chess.com. I am White.

4. “Positive review only” prompts in papers.

5. New Alex Rosenberg book on economic method and game theory.

6. The impact of logistics robots?

7. 46.9% of Pakistan’s federal budget will go toward debt servicing.

8. Very good Robert Colville Op-Ed on Britain (The Times).

Trump Accounts are a Big Deal

Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill Act was signed into law on July 4, 2025. It’s so big that many significant features have been little discussed. Trump Accounts are one such feature under which every newborn citizen gets $1000 invested in the stock market. These accounts could radically change social welfare in the United States and be one important step on the way to a UBI or UBWealth. Here are some details:

- Government Contribution: A one-time $1,000 contribution per eligible child, invested in a low-cost, diversified U.S. stock index fund.

- Eligibility: U.S. citizen children born between January 1, 2025, and December 31, 2028 (with a valid Social Security number and at least one parent with a valid Social Security number).

- Employer Contributions: Employers can contribute up to $2,500 annually per employee’s child, and these contributions are excluded from the employee’s gross income for tax purposes. These are subject to the overall $5,000 annual contribution limit (indexed for inflation) per child (which includes parental contributions).

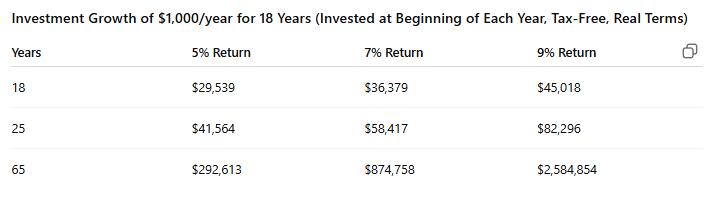

The employer contribution strikes me as important. Suppose that in addition to the initial $1000 government payment that on average $1000 is added per year for 18 years (by a combination of parent and parent employer contributions). Note that this is below the maximum allowed annual contribution of $5000. At a historically reasonable 7% real rate of return these accounts will be worth ~36k at age 18 (when the money can be fully withdrawn), $58k at age 25 and $875k at age 65 subject to uncertainty of course as indicated below.

The $1000 initial payment is available only for newborns but, as I read the text, the parent and employer donations can be made for any child under the age of 18 so this is basically an IRA for children. It’s slightly complicated because if the child or parents put after-tax money into the account that is not taxed at withdrawal (you get your basis back) but everything else is taxed on withdrawal as ordinary income like an IRA. There are approximately 3.5 million citizen births a year so the program will have direct costs of $3.5 billion plus indirect costs from reduced taxes due to the tax-free yearly contribution allowance, which as noted could be quite large as it can go to any child. Thus the program could be quite expensive. On the other hand, it’s clear that the accounts could reduce reliance on social security if held for long periods of time. The $1000 initial contribution is limited to four years but once 14 million kids get them, the demand will be to make them permanent.

Emotions and Policy Views

I would call this a story of negative emotional contagion:

This paper investigates the growing role of emotions in shaping policy views. Analyzing social citizens’ media postings and political party messaging over a large variety of policy issues from 2013 to 2024, we document a sharp rise in negative emotions, particularly anger. Content generating anger drives significantly more engagement. We then conduct two nationwide online experiments in the U.S, exposing participants to video treatments that induce positive or negative emotions to measure their causal effects on policy views. The results show that negative emotions increase support for protectionism, restrictive immigration policies, redistribution, and climate policies but do not reinforce populist attitudes. In contrast, positive emotions have little effect on policy preferences but reduce populist inclinations. Finally, distinguishing between fear and anger, we find that anger exerts a much stronger influence on citizens’ policy views, in line with its growing presence in the political rhetoric.

That is from a new paper by Eva Davoine, Stefanie Stantcheva, Thomas Renault, and Yann Algan.