Side-Walking Problems

Local Law 11 requires owners of New York City’s 16,000-plus buildings over six stories to get a “close-up, hands-on” facade inspection every five years. Repair costs in NYC’s bureaucratic and labor-union driven system are very high, so the owners throw up “temporary” plywood sheds that often sit there for a decade. NYC now has some 400 miles of ugly sheds.

The ~9,000 sheds stretching nearly 400 miles have installation costs around $100–150 per linear foot and ongoing rents of about 5–6% of that per month, implying something like $150 million plus a year in shed rentals citywide.

Well. at last something is being done! The sheds are being made prettier! Six new designs, some with transparent roofs as in the rendering below are now allowed. Looks nice in the picture. Will it look as nice in real life? Will it cost more? Almost certainly!

To be fair, City Hall is cracking down as well as doubling down: new laws cut shed permits from a year to three months and ratchet up fines for letting sheds linger. That’s a good idea. But the prettier sheds are the tell. Instead of reevaluating the law, doing a cost-benefit test or comparing with global standards, NYC wants to be less ugly.

How about using drones and AI to inspect buildings? Singapore requires inspections every 7 years but uses drones to do most of the work with a follow-up with hands-on check. How about investigating ways to cut the cost of repair? The best analysis of NYCs facade program indicates something surprising–the problem isn’t just deteriorating old buildings but also poorly installed glass in new buildings, thus more focus on installation quality is perhaps warranted. Moreover, are safety resources being optimized? Instead of looking up, New Yorkers might do better by looking down. Stray voltage continues to kill pets and shock residents. Manhole “incidents” including explosions happen in the thousands every year! What’s the best way to allocate a dollar to save a life in NYC?

Instead of dealing the with the tough but serious problems, NYC has decided to put on the paint.

Big, Fat, Rich Insurance Companies

In my post, Horseshoe Theory: Trump and the Progressive Left, I said:

Trump’s political coalition isn’t policy-driven. It’s built on anger, grievance, and zero-sum thinking. With minor tweaks, there is no reason why such a coalition could not become even more leftist. Consider the grotesque canonization of Luigi Mangione, the (alleged) murderer of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson. We already have a proposed CA ballot initiative named the Luigi Mangione Access to Health Care Act, a Luigi Mangione musical and comparisons of Mangione to Jesus. The anger is very Trumpian.

In that light, consider one of Trump’s recent postings:

THE ONLY HEALTHCARE I WILL SUPPORT OR APPROVE IS SENDING THE MONEY DIRECTLY BACK TO THE PEOPLE, WITH NOTHING GOING TO THE BIG, FAT, RICH INSURANCE COMPANIES, WHO HAVE MADE $TRILLIONS, AND RIPPED OFF AMERICA LONG ENOUGH.

Confidently Wrong

If you’re going to challenge a scientific consensus, you better know the material. Most of us, most of the time, don’t—so deferring to expert consensus is usually the rational strategy. Pushing against the consensus is fine; it’s often how progress happens. But doing it responsibly requires expertise. Yet in my experience the loudest anti-consensus voices—on vaccines, climate, macroeconomics, whatever—tend to be the least informed.

This isn’t just my anecdotal impression. A paper by Light, Fernbach, Geana, and Sloman shows that opposition to the consensus is positively correlated with knowledge overconfidence. Now you may wonder. Isn’t this circular? If someone claims the consensus view is wrong we can’t just say that proves they don’t know what they are talking about. Indeed. Thus Light, Fernbach, Geana and Sloman do something clever. They ask respondents a series of questions on uncontroversial scientific topics. Questions such as:

1. True or false? The center of the earth is very hot: True

2. True or false? The continents have been moving their location for millions of years and will continue to move. True

3. True or false? The oxygen we breathe comes from plants: True

4. True or false? Antibiotics kills viruses as well as bacteria: False

5. True or false? All insects have eight legs: False

6. True or false? All radioactivity is man made: False

7. True or false? Men and women normally have the same number of chromosomes: True

8. True or false? Lasers work by focusing sound waves: False

9. True or false? Almost all food energy for living organisms comes originally from sunlight: True

10. True or false? Electrons are smaller than atoms: True

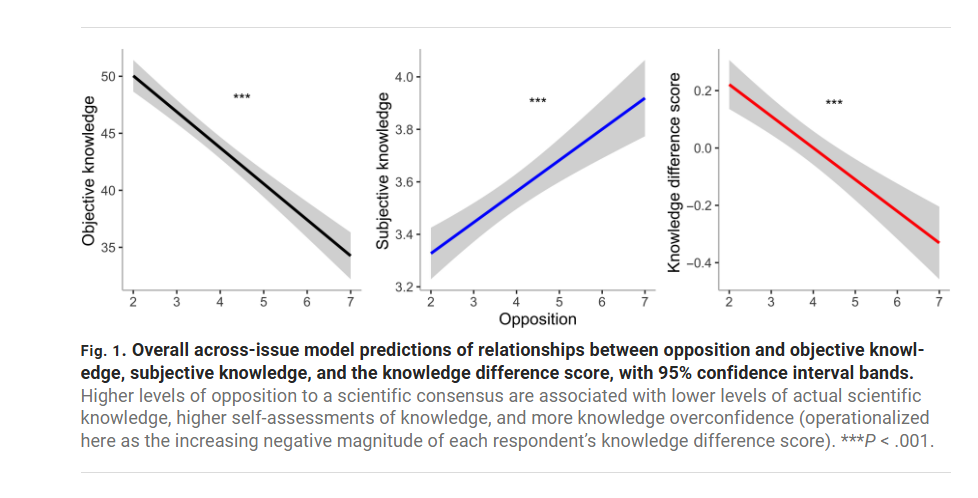

The authors then correlate respondents’ scores on the objective (uncontroversial) knowledge with their opposition to the scientific consensus on topics like vaccination, nuclear power, and homeopathy. The result is striking: people who are most opposed to the consensus (7, the far right of the horizontal axis in the figure below) score lower on objective knowledge but express higher subjective confidence. In other words, anti-consensus respondents are the most confidently wrong—the gap between what they know and what they think they know is widest.

In a nice test the authors show that the confidently wrong are not just braggadocios they actually believe they know because they are more willing to bet on the objective knowledge questions and, of course, they lose their shirts. A bet is a tax on bullshit.

The implications matter. The “knowledge deficit” approach (just give people more fact) breaks down when the least-informed are also the most certain they’re experts. The authors suggest leaning on social norms and respected community figures instead. My own experience points to the role of context: in a classroom, the direction of information flow is clearer, and confidently wrong pushback is rarer than on Twitter or the blog. I welcome questions in class—they’re usually great—but they work best when there’s at least a shared premise that the point is to learn.

Hat tip: Cremieux

The MR Podcast: Tariffs!

On The Marginal Revolution Podcast this week, Tyler and I discuss tariffs! Here’s one bit:

COWEN: I have a new best argument against tariffs. It’s very soft. I think it’s hard to prove, but it might actually be the very best argument against tariffs.

TABARROK: All right, let’s hear it.

COWEN: If you think about COVID policy, the wealthy nations did a bunch of things. Some of them were quite bad, and the poorer nations all copied that. They didn’t have to copy it, but there was some kind of contagion effect, or that seemed like the high-status thing to do. I believe with tariffs, something similar goes on. There’s a huge literature about retaliation. Of course, retaliation is a cost, that’s bad, but simply the copying effect that it was high status for the wealthy nations to have tariffs. They can afford it better, but then places like India had their own version of the same thing. That was just terrible for India at a much higher human cost than, say, it was for the United States. Again, it’s hard to trace or prove, but that I think could actually be the best argument against tariffs, simply that poorer countries will copy what the high-status nations are doing.

This is like Rob Henderson’s idea of luxury beliefs, beliefs which the elite can proffer at low cost but which have negative consequences when adopted by working and lower classes. Tariffs aren’t great for the US but the US is so large and rich we can handle it but if the idea is adopted by poorer nations it will be much worse for them. I wish I had been clever enough to say this during the podcast but I never know what Tyler will say in advance.

Here’s another bit:

TABARROK: Here’s the question which the Trumpers or other people never really answer is, what are we going to have less of? Yes, we’ll have more investment. Let’s say we get another auto plant. The unemployment rate is 4%, so it’s not like we have a lot of free resources around. Most of the time, we’re in full equilibrium. If we have more auto plant workers and more cars being produced in the United States, we’re going to have less of something. I think it is incumbent on people who want tariffs in order to get more employment in manufacturing or something like that to say, “Well, what are we going to have less of?”

COWEN: The more sophisticated ones of them, I think, would say, well, the US is super high on the consumption scale, even relative to our very high per capita incomes. If we end up spending some of that consumption on boosting real wages, it’s actually a good investment, if only in political sanity, stability, fewer opioid deaths. It’s a very indirect chain of reasoning. I would say I’m skeptical. Again, it’s not a crazy argument. It’s a weird kind of industrial policy where you channel resources away from consumption into investment and higher wages. A lot of those plants are automated. They’re going to be automated much yet. It’s further stuff, maybe to other robotics companies or the AI companies. Again, I think that’s what they would say.

TABARROK: I don’t think they would say that.

COWEN: No, the more sophisticated ones.

TABARROK: Are there? I haven’t seen too many of those….

Here’s the episode. Subscribe now to take a small step toward a much better world: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | YouTube.

Illegal Immigrants Didn’t Break the Housing Market; Bad Policy Did

In an interview, JD Vance claimed:

[H]ousing is way too expensive….because we flooded the country with 30 million illegal immigrants who were taking houses that ought by right go to American citizens.

I noted on Twitter that this framing reeks of socialist thinking, national socialist to be precise. A demand for the state to designate a privileged class that get special rights to scarce goods. Treating housing as a fixed stock to be allocated to a favored in-group while blaming an out-group for shortages is collectivist politics driven by grievance, not market reasoning. In short, grievance and entitlement, zero-sum thinking and central planning wrapped into one ugly bundle.

That criticism set people off. The first rebuttal was predictable “Ha ha, the economist forgot about supply and demand!”—a miss, because my point wasn’t about the mechanics of house-price growth but about Vance’s rhetoric: the collectivism and the cheap politics of blaming outsiders. The second rebuttal was that “America belongs to Americans” so of course illegal immigrants shouldn’t be allowed to buy homes.

The second objection is amusing because who is harmed most when a government bans immigrants from buying homes or deports a chunk of potential buyers? American home sellers. The way such bans “work” is by preventing sellers from accepting the highest bid. In effect, these policies are a tax on sellers combined with a subsidy to a subset of buyers.

So bans on foreign buyers are really about taxing some Americans and subsidizing others. Moreover, although the economic logic of illegals pushing up demand is sound, the numbers don’t add up to much. First, there aren’t 30 million illegals; the best estimates are roughly 14 million. And second illegals are obviously not the reason homes blow past a million dollars in places like San Francisco, San Jose, Washington, or New York! The effect of illegal immigrant on house prices exists but is small—the bigger factors are native population growth, rising incomes, zoning rules, and strict limits on new construction. Block illegal immigrants from buying homes and you will get a pause in price growth, but once demand from natives keeps rising against a capped supply, prices will climb back to where they were.

That gets to the deeper problem with Vance’s style of thinking. If “fixing” housing scarcity means blaming whichever group is politically convenient, you end up cycling through targets: illegal immigrants first, then legal immigrants (as Canada has done), then the children of immigrants, then wealthy buyers, then racial or religious minorities. Indeed, one wonders if the blame is the goal.

If you actually want to solve the problem of housing scarcity, stop the scapegoating and start supporting the disliked people who are actually working to reduce scarcity: the developers. Loosen zoning and cut the rules that choke what can be built. Redirect political energy away from trying to demolish imagined enemies and instead build, baby, build.

Wise Words Addendum (hat tip G. Scott Shand):

There is a cultural movement in the white working class to blame problems on society or the government, and that movement gains adherents by the day….We’ll get fired for tardiness, or for stealing merchandise and selling it on eBay, or for having a customer complain about the smell of alcohol on our breath, or for taking five thirty-minute restroom breaks per shift. We talk about the value of hard work but tell ourselves that the reason we’re not working is some perceived unfairness: Obama shut down the coal mines, or all the jobs went to the Chinese. These are the lies we tell ourselves to solve the cognitive dissonance—the broken connection between the world we see and the values we preach.

Why are US Clinical Trials so Expensive?

Dave Ricks, CEO of Eli Lilly, speaking on the excellent Cheeky Pint Podcast (hosted by John Collison, sometimes joined by Patrick as in this episode) had the clearest discussion of why US clinical trial costs are so expensive that I have read.

One point is obvious once you hear it: Sponsors must provide high-end care to trial participants–thus because U.S. health care is expensive, US clinical trials are expensive. Clinical trial costs are lower in other countries because health care costs are lower in other countries but a surprising consequence is that it’s also easier to recruit patients in other countries because sponsors can offer them care that’s clearly better than what they normally receive. In the US, baseline care is already so good, at least at major hospital centers where you want to run clinical trials, that it’s more difficult to recruit patients. Add in IRB friction and other recruitment problems, and U.S. trial costs climb fast.

Patrick

I looked at the numbers. So, apparently the median clinical trial enrollee now costs $40,000. The median US wage is $60,000, so we’re talking two thirds. Why and why couldn’t it be a 10th or a hundredth of what it is?David (00:10:50):

Yeah, brilliant question and one we’ve spent a lot of time working on…“Why does a trial cost so much?” Well, we’re taking the sickest slice of the healthcare system that are costing the most. And we’re ingesting them. We’re taking them out of the healthcare system and putting them in a clinical trial. Typically we pay for all care. So we are literally running the healthcare system for those individuals and that is in some ways for control, because you want to have the best standard of care so your experiment is properly conducted and it’s not just left to the whims of hundreds of individual doctors and people in Ireland versus the US getting different background therapies. So you standardize that, that costs money because sort of leveling up a lot of things, but then also in some ways you’re paying a premium to both get the treating physicians and have great care to get the patient. We don’t offer them remuneration, but they get great care and inducement to be in the study because you’re subjecting yourself quite often, not all the case, but to something other than the standard of care, either placebo or this. Or, in more specialized care, often it’s standard care plus X where X could actually be doing harm, not good. So people have to go into that in a blinded way and I guess the consideration is you’ll get the best care.Patrick (00:12:51):

Of the $40,000. How much of that should I look at as inducement and encouragement for the patient and how much should I look at it as the cost of doing things given the regulatory apparatus that exists?David (00:13:02):

The patient part is the level up part and I would say 20, 30% of the cost of studies typically would be this. So you’re buying the best standard of care, you’re not getting something less. That’s medicine costs, you’re getting more testing, you’re getting more visits, and then there is a premium that goes to institutions, not usually to the physician, the institution to pay for the time of everybody involved in it plus something. We read a lot about it in the NIH cuts, the 60% Harvard markup or whatever. There’s something like that in all clinical trials too. Overhead coverage, whatnot. But it’s paying for things that aren’t in the trial.Patrick (00:13:40):

US healthcare is famously the most expensive in the world. Yes. Do you run trials outside the US?David (00:13:44):

Yeah, actually most. I mean we want to actually do more in the US. This is a problem I think for our country. Take cancer care where you think, okay, what’s the one thing the US system’s really good at? If I had cancer, I’d come to the US, that’s definitely true. But only 4% of patients who have cancer in the US are in clinical trials. Whereas in Spain and Australia it’s over 25%.And some of that is because they’ve optimized the system so it’s easier to run and then enroll, which I’d like to get to, people in the trials. But some of it is also that the background of care isn’t as good. So that level up inducement is better for the patient and the physician. Here, the standard’s pretty good, so people are like, “Do I want to do something where there’s extra visits and travel time?” There’s another problem in the US which is, we have really good standards of care but also quite different performing systems and we often want to place our trials in the best performing systems that are famous, like MD Anderson or the Brigham. And those are the most congested with trials and therefore they’re the slowest and most expensive. So there’s a bit of a competition for place that goes on as well.

But overall, I would say in our diabetes and cardiovascular trials, many, many more patients are in our trials outside the US than in and that really shouldn’t be other than cost of the system. And to some degree the tuning of the system, like I mentioned with Spain and Australia toward doing more clinical trials. For instance, here in the US, everywhere you get ethics clearance, we call it IRB. The US has a decentralized system, so you have to go to every system you’re doing a study in. Some countries like Australia have a single system, so you just have one stop and then the whole country is available to recruit those types of things.

Patrick (00:15:31):

You said you want to talk about enrollment?David (00:15:32):

Yeah, yeah. It’s fascinating. So drug development time in the industry is about 10 years in the clinic, a little less right now. We’re running a little less than seven at Lilly, so that’s the optimization I spoke about. But actually, half of that seven is we have a protocol open, that means it’s an experiment we want to run. We have sites trained, they’re waiting for patients to walk in their door and to propose, “Would you like to be in the study?” But we don’t have enough people in the study. So you’re in the serial process, diffuse serial process, waiting for people to show up. You think, “Wow, that seems like we could do better than that. If Taylor Swift can sell at a concert in a few seconds, why can’t I fill an Alzheimer’s study? There seem to be lots of patients.” But that’s healthcare. It’s very tough. We’ve done some interesting things recently to work around that. One thing that’s an idea that partially works now is culling existing databases and contacting patients.Patrick (00:16:27):

Proactive outreach.

See also Chertman and Teslo at IFP who have a lot of excellent material on clinical trial abundance.

Lots of other interesting material in this episode including how Eli Lilly Direct—driven largely by Zepbound—has quickly become a huge pharmacy. The direct-to-consumer model it represents could be highly productive as more drugs for preventing disease are developed. I am not as anti-PBM as Ricks and almost everyone in the industry are but I will leave that for another day.

Here is the Cheeky Pint Podcast main page.

Waymo

Waymo now does highways in the Bay area.

Expanding our service territory in the Bay Area and introducing freeways is built on real-world performance and millions of miles logged on freeways, skillfully handling highway dynamics with our employees and guests in Phoenix, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. This experience, reinforced by comprehensive testing as well as extensive operational preparation, supports the delivery of a safe and reliable service.

The future is happening fast.

UCSD Faculty Sound Alarm on Declining Student Skills

The UC San Diego Senate Report on Admissions documents a sharp decline in students’ math and reading skills—a warning that has been sounded before, but this time it’s coming from within the building.

At our campus, the picture is truly troubling. Between 2020 and 2025, the number of freshmen whose math placement exam results indicate they do not meet middle school standards grew nearly thirtyfold, despite almost all of these students having taken beyond the minimum UCOP required math curriculum, and many with high grades. In the 2025 incoming class, this group constitutes roughly one-eighth of our entire entering cohort. A similarly large share of students must take additional writing courses to reach the level expected of high school graduates, though this is a figure that has not varied much over the same time span.

Moreover, weaknesses in math and language tend to be more related in recent years. In 2024, two out of five students with severe deficiencies in math also required remedial writing instruction. Conversely, one in four students with inadequate writing skills also needed additional math preparation.

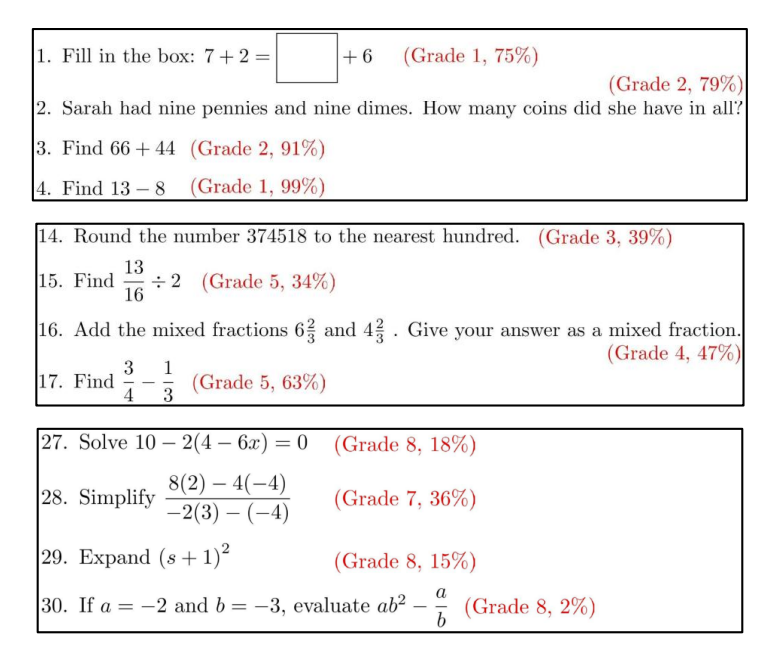

The math department created a remedial course, only to be so stunned by how little the students knew that the class had to be redesigned to cover material normally taught in grades 1 through 8.

Alarmingly, the instructors running the 2023-2024 Math 2 courses observed a marked change in the skill gaps compared to prior years. While Math 2 was designed in 2016 to remediate missing high school math knowledge, now most students had knowledge gaps that went back much further, to middle and even elementary school. To address the large number of underprepared students, the Mathematics Department redesigned Math 2 for Fall 2024 to focus entirely on elementary and middle school Common Core math subjects (grades 1-8), and introduced a new course, Math 3B, so as to cover missing high-school common core math subjects (Algebra I, Geometry, Algebra II or Math I, II, III; grades 9-11).

In Fall 2024, the numbers of students placing into Math 2 and 3B surged further, with over 900 students in the combined Math 2 and 3B population, representing an alarming 12.5% of the incoming first-year class (compared to under 1% of the first-year students testing into these courses prior to 2021)

(The figure gives some examples of remedial class material and the percentage of remedial students getting the answers correct.)

The report attributes the decline to several factors: the pandemic, the elimination of standardized testing—which has forced UCSD to rely on increasingly inflated and therefore useless high school grades—and political pressure from state lawmakers to admit more “low-income students and students from underrepresented minority groups.”

…This situation goes to the heart of the present conundrum: in order to holistically admit a diverse and representative class, we need to admit students who may be at a higher risk of not succeeding (e.g. with lower retention rates, higher DFW rates, and longer time-to-degree).

The report exposes a hard truth: expanding access without preserving standards risks the very idea of a higher education. Can the cultivation of excellence survive an egalitarian world?

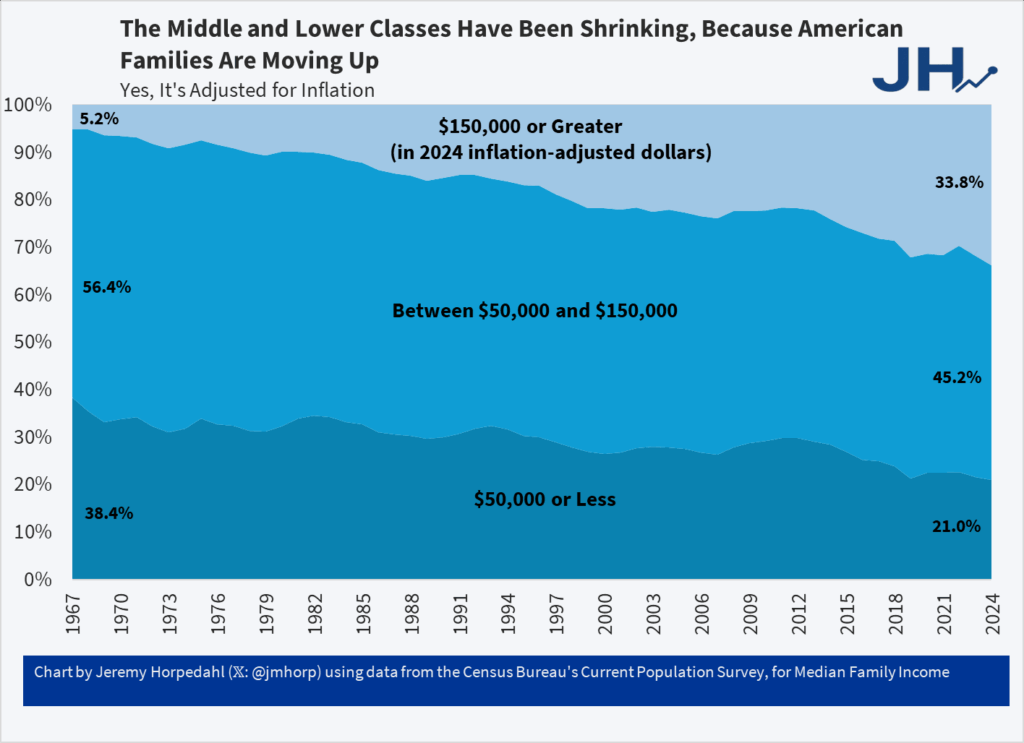

One-Third of US Families Earn Over $150,000

It’s astonishing that the richest country in world history could convince itself that it was plundered by immigrants and trade. Truly astonishing.

From Jeremy Horpedahl who notes:

This is from the latest Census release of CPS ASEC data, updated through 2024 (see Table F-23 at this link).

In 1967, only 5 percent of US families earned over $150,000 (inflation adjusted).

And even though it says so in the chart and in the text let me say it again, this is inflation adjusted and so yes it’s real and no the fact that housing has gone up in price doesn’t negate this, it’s built in. We would have done even better had NIMBYs not reduced the supply of housing.

See also Asness and Strain.

Addendum: Note it isn’t the rise of dual-earner households which haven’t increased for over 30 years.

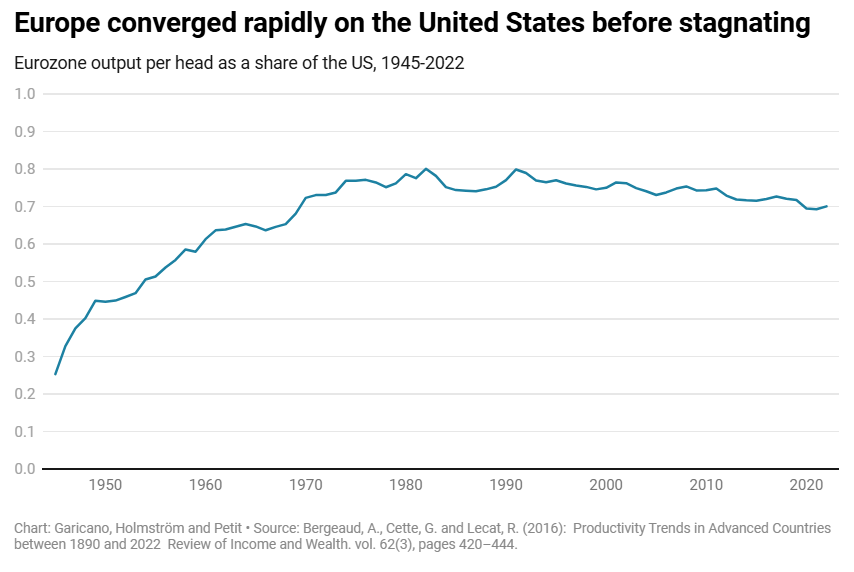

European Stagnation

Excellent piece by Luis Garicano, Bengt Holmström & Nicolas Petit.

The continent faces two options. By the middle of this century, it could follow the path of Argentina: its enormous prosperity a distant memory; its welfare states bankrupt and its pensions unpayable; its politics stuck between extremes that mortgage the future to save themselves in the present; and its brightest gone for opportunities elsewhere. In fact, it would have an even worse hand than Argentina, as it has enemies keen to carve it up by force and a population that would be older than Argentina’s is today.

Or it could return to the dynamics of the trente glorieuses. Rather than aspire to be a museum-cum-retirement home, happy to leave the technological frontier to other countries, Europe could be the engine of a new industrial revolution. Europe was at the cutting edge of innovation in the lifetime of most Europeans alive today. It could again be a continent of builders, traders and inventors who seek opportunity in the world’s second largest market.

The European Union does not need a new treaty or powers. It just needs a single-minded focus on one goal: economic prosperity.

I’ve quoted the call to arms but there is much more substantive and deep analysis. Naturally, I approve of this theme “If a product is safe enough to be sold in Lisbon, it should be safe enough for Berlin.” Not the usual fare, read the whole thing.

More From Less: Optimizing Vaccine Doses

During COVID, I argued strongly that we should cut the Moderna dose in order to expand supply. In a paper co-authored with Witold Więcek, Michael Kremer and others, we showed that a half dose of Moderna was more effective than a full dose of AstraZenecs and that doubling the effective Moderna supply could have saved many lives.

It’s not just about COVID. My co-author on the COVID paper, Witold Więcek, has found other examples where a failure to run dose optimization trials cost lives:

Take the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine. For years after its introduction, countries administered it as a three-dose series. Then additional evidence emerged; eventually, a single dose proved to be non-inferior. This policy shift, driven by updated World Health Organization (WHO) guidance, has been a game-changer—massively reducing delivery costs while expanding coverage in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). But it took 16 years from regulatory approval to WHO recommendation. Had this change been implemented just five years earlier, the paper estimates that 150,000 lives could have been saved.

Knowing the potential for dose optimization should encourage us to take a closer look at what we can do now. Więcek points to two high-opportunity projects:

- The pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) is already Gavi’s top cost driver, consuming $1 billion of its 2026–2030 budget. But new WHO SAGE guidance, from March 2025, suggests that in countries with consistently high coverage (≥80–90 percent over five years), either one of three shots could be dropped, or each of the three doses can be lowered to 40 percent of the standard dose. While implementation requires sufficient epidemiological surveillance, its cost would be offset by significant savings in vaccine costs: a retrospective analysis suggests that for the 2020–25 period this approach could have led to as much as $250 million in savings.

- New tuberculosis vaccines, currently in phase 2–3 trials, are another high-impact example. Given initial promising results, a future vaccine could prove highly effective, but may also become a significant cost driver for countries and/or Gavi—and optimization may prove highly beneficial both in terms of health and economic value.

Witold’s new paper is here and here is excellent summary blog post from which I have drawn.

Addendum: See also my paper on Bayesian Dose Optimization Trials and from Mike Doherty Particles that enhance mRNA delivery could reduce vaccine dosage and costs.

Creative Stagnation

Legislation requiring cars and trucks, including electric vehicles, to have AM radios easily cleared a House committee Wednesday, although it could run into opposition going forward.

H.R. 979, the “AM Radio for Every Vehicle Act,” would require the Department of Transportation to enforce the mandate through a rulemaking. It passed the Energy and Commerce Committee by a 50-1 vote. Rep. Jay Obernolte (R-Calif.) was the only “no.”

What’s next—mandating 8-track players in every car? Fax machines in every home? Floppy disks in every laptop? If Congress actually cared about emergency communication, it would strengthen cellular networks, not cling to obsolete technology. Congress is a den of old busybodies.

Hat tip: Nick Gillespie.

Addendum: If AM radio is so valuable for emergencies then the market will provide or you could, you know, put an AM radio in your glove box. No need for a mandate. We already have FM, broadcast TV, cable, satellite, cell, and Wireless Emergency Alerts; resilience can be met without specifying AM hardware.

Here Comes the Sun—If We Let It: Cutting Tariffs and Red Tape for Rooftop Solar

Australia has so much rooftop solar power that some states are offering free electricity during peak hours:

TechCrunch: For years, Australians have been been installing solar panels at a rapid clip. Now that investment is paying off.

The Australian government announced this week that electricity customers in three states will get free electricity for up to three hours per day starting in July 2026.

Solar power has boomed in Australia in recent years. Rooftop solar installations cost about $840 (U.S.) per kilowatt of capacity before rebates, about a third of what U.S. households pay. As a result, more than one in three Australian homes have solar panels on their roof.

Why is rooftop solar adoption in the U.S. lagging behind Australia, Europe, and much of Asia? Australia has roughly as many rooftop installations as the entire United States, despite having less than a tenth of its population.

First, tariffs. U.S. tariffs on imported solar panels mean American buyers pay double to triple the global market rate.

Second, permits. The U.S. permitting process is slow, fragmented, and expensive. In Australia, no permit is required for a standard installation—you simply notify the distributor and have an accredited installer certify safety. In Australia, a rooftop solar panel is treated like an appliance; in the U.S., it’s treated like a mini power plant. Germany takes a similar approach to Australia, with national standards and an “as-of-right” presumption for rooftop solar that removes red tape.

By contrast, the U.S. system involves multiple layers of approval—building and electrical permits, several inspections, and a Permission-to-Operate from the local utility, which may not be eager to speed things up just to lose your business. Moreover, each of thousands of jurisdictions has different requirements, creating long delays and high costs.

High costs suppress adoption, limiting economies of scale and forcing installers to spend more on sales than installation. Yet Australia and Germany are not so different from the United States—they simply made solar easy. If the U.S. eliminated tariffs, standardized/nationalized rules, and accelerated approvals, rooftop solar would take off, costs would fall, and innovation would follow.

The benefits extend beyond cheaper power. Distributed rooftop generation makes the grid more resilient. Streamlining solar policy would thus cut energy costs, strengthen protection against disasters and disruptions, and speed the transition to a future with more abundant and cleaner power.

The MR Podcast: Our Favorite Models, Session 3: Compensating Differentials and Selective Incentives

On The Marginal Revolution Podcast this week, Tyler and I discuss compensating differentials and Olsonian selective incentives. Here’s one bit:

If you think about the gender wage gap, it’s sometimes said that women earn—it varies—80 cents for every dollar that a man earns. That doesn’t control for anything. Once you control for education and skill and so forth, this gets smaller. Then you also have to control for these quite difficult, elusive sometimes, job amenities. Claudia Goldin, for example, has pointed out that men are much more willing to take jobs requiring inflexible hours.

COWEN: And longer hours, too.

TABARROK: Longer hours and inflexible hours, where your hours are less under your control. That’s what I mean by inflexible. For example, in one study of train and bus drivers, the train and bus drivers are paid equally by gender. There’s no differences whatsoever in what they’re paid on an hourly basis. It turns out that the male drivers, their wages, their returns are much higher because they take a lot more overtime. They take 83% more overtime than their female colleagues. They’re much more likely to accept an overtime shift, which pays time and a half. The male workers also take fewer unpaid hours off. The male salaries on a yearly basis end up being higher, even though males and females are paid equally.

Now, you can roll this back and say that’s because of the unfair demands on women of childcare or something like that, but it’s not a market discrimination. It’s not market discrimination. It’s a compensating differential. Males earn more because they’re more willing to take the inflexible overtime hours and so forth.

One of the most interesting ones is that Uber drivers, male drivers earn a little bit more. Now, obviously, there’s no gender difference whatsoever in how the drivers are paid. It just turns out that male drivers just drive a little bit faster.

COWEN: I’ve noticed this, by the way, when I take Ubers.

TABARROK: On an annual basis, they make about 7% more. Now, again, it’s not entirely obvious that this is even better for the male drivers. Maybe they’re taking a little bit more risk. Maybe they’re a little bit more likely to get into an accident as well.

….COWEN: …Someone gets the short end of the stick. Not only women, but maybe women on average would be more likely to suffer.

TABARROK: I’m not sure it’s the short end of the stick, though I agree with increasing returns, that the people who work longer hours will also earn higher salaries and maybe have plush offices and so forth. Let me put it this way. One of the things which I think the feminism story sometimes gets a little bit wrong is to actually underestimate the value that women get, and that men can get as well, of childcare, of looking after kids, of spending more time at home, or spending more time doing childcare. That can be extremely valuable. At the end of life, who writes on their tombstone, “I wish I could have worked more”?

COWEN: You’re looking at one.

TABARROK: Present company excepted.

Here’s the episode. Subscribe now to take a small step toward a much better world: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | YouTube.

How Cultural Diversity Drives Innovation

It is hardly possible to overrate the value…of placing human beings in contact with persons dissimilar to themselves, and with modes of thought and action unlike those with which they are familiar….Such communication has always been, and is peculiarly in the present age, one of the primary sources of progress.

Mill had in mind the civilizing force of commerce but the idea is far more general. My colleague Jonathan Schulz with Max Posch and Joe Henrich have a novel and important test of the idea in a paper forthcoming in the JPE: How Cultural Diversity Drives Innovation (WP; SSRN). They show that the more diverse a county, as measured by surnames, the more ideas and the more novel ideas were patented in that county.

We show that innovation in U.S. counties from 1850 to 1940 was propelled by shifts in the local social structure, as captured using the diversity of surnames. Leveraging quasi-random variation in counties’ surnames—stemming from the interplay between historical fluctuations in immigration and local factors that attract immigrants—we find that more diverse social structures increased both the quantity and quality of patents, likely because they spurred interactions among individuals with different skills and perspectives. The results suggest that the free flow of information between diverse minds drives innovation and contributed to the emergence of the U.S. as a global innovation hub.